Taha Hussein

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Taha Hussein | |

|---|---|

Taha Hussein | |

| Native name | طه حُسين |

| Born | November 15, 1889[1] Maghagha, Minya Governorate |

| Died | October 28, 1973(1973-10-28) (aged 83)[1] Cairo, Egypt |

| Nationality | Egyptian |

| Era | Modern literary theory |

| Region | Egyptian philosophy |

| School | Modernism, Classical Arabic literature, El Nahda |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

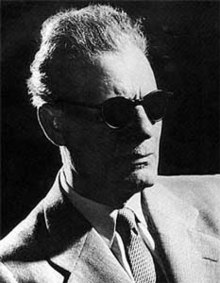

Taha Hussein (November 15, 1889 – October 28, 1973; Egyptian Arabic: [ˈtˤɑːhɑ ħ(e)ˈseːn]) was one of the most influential 20th-century Egyptian writers and intellectuals, and a figurehead for The Egyptian Renaissance and the modernist movement in the Middle East and North Africa. His sobriquet was "The Dean of Arabic Literature" (Fr. doyen des lettres arabes).[2]

He was nominated for a Nobel prize in literature fourteen times.[3]

Contents

1 Life

2 Academic career

3 Positions and tasks

3.1 Works

3.2 Translations

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

Life

Taha Hussein was born in Izbet el Kilo, a village in the Minya Governorate in central Upper Egypt. He went to a kuttab, and thereafter was admitted to El Azhar University, where he studied Religion and Arabic literature. From an early age, he was reluctant to take the traditional education to his heart. Hussein was the seventh of thirteen children, born into a lower-middle-class family. He became blind at the age of three, the result of faulty treatment by an unskilled practitioner, a condition which caused him a great deal of anguish throughout his entire life.

Hussein met and married Suzanne Bresseau (1895–1989) while attending the University of Montpellier in France. She was referred to as "sweet voice". This name came from her ability to read to him as he was trying to improve his grasp of the French language. Suzanne became his wife, best friend and the mother of his two children and was his mentor throughout his life.

Taha Hussein's children, his daughter Amina and her younger brother Moenis, were both important figures in Egypt. Amina, who died at the age of 70, was among the first Egyptian women to graduate from Cairo University. She and her brother, Moenis, translated his Adib (The Intellectual) into French. This was especially important to their father, who was an Egyptian who had moved to France and learned the language. Even more important, the character of Adib is that of a young man who, like Taha Hussein, has to deal with the cultural shock of an Egyptian studying and living in France.[citation needed]

Academic career

When the secular Cairo University was founded in 1908, he was keen to be admitted, and despite being blind and poor he won a place. In 1914, he became the second graduate to receive a PhD, with a thesis on the sceptic poet and philosopher Abu-Alala' Al-Ma'ari. He went on to become a professor of Arabic literature there. In 1919, he was appointed a professor of history at Cairo University. Additionally, he was the founding Rector of the University of Alexandria. Although he wrote many novels and essays, in the West he is best known for his autobiography, Al-Ayyam (الايام, The Days) which was published in English as An Egyptian Childhood (1932) and The Stream of Days (1943). However, it was his book of literary criticism On Pre-Islamic Poetry (في الشعر الجاهلي) of 1926 that bought him some fame in the Arab world.[4] In this book, he expressed doubt about the authenticity of much early Arabic poetry, claiming it to have been falsified during ancient times due to tribal pride and rivalry between tribes. He also hinted indirectly that the Qur'an should not be taken as an objective source of history. Consequently, the book aroused the intense anger and hostility of the religious scholars at Al Azhar and many other traditionalists, and he was accused of having insulted Islam. However, the public prosecutor stated that what Taha Hussein had said was the opinion of an academic researcher and no legal action was taken against him, although he lost his post at Cairo University in 1931. His book was banned but was re-published the next year with slight modifications under the title On Pre-Islamic Literature (1927).

Taha Hussein was an intellectual of the Egyptian Renaissance and a proponent of the ideology of Egyptian nationalism along with what he called Pharaonism, believing that Egyptian civilization was diametrically opposed to Arab civilization, and that Egypt would only progress by reclaiming its ancient pre-Islamic roots.[5]

After Hussein obtained his MA from the University of Montpellier, he continued his studies and received another PhD at the Sorbonne. With this accomplishment, Hussein became the first Egyptian and member of the mission to receive an MA and a doctorate (PhD) from France. For his doctoral dissertation, written in 1917, Hussein wrote on Ibn Khaldun, a Tunisian historian, claimed by some to be the founder of sociology. Two years later, in 1919, Hussein made his way back to Egypt from France with his wife, Suzanne, and was appointed professor of history at Cairo University.

In 1950, Hussein was appointed Minister of Education, and was able to put into action his motto: "Education is like the air we breathe and the water we drink." Mr. Farid Shehata was his personal secretary and his eyes and ears during this period. Without Taha Hussein and his passion to promote education, millions of Egyptians would never have become literate.

Positions and tasks

In 1950, he was appointed a Minister of Knowledge (Ministry of Education nowadays) in which capacity he led a call for free education and the right of everyone to be educated. Additionally, he was an advocate against the confinement of education to the rich people only. In that respect, he said, "Education is as water and air, the right of every human being". Consequently, in his hands, education became free and Egyptians started getting free education. He also transformed many of the Quranic schools into primary schools and converted a number of high schools into colleges such as the Graduate Schools of Medicine and Agriculture. He is also credited with establishing a number of new universities.

Taha Hussein held the position of chief editor of a number of newspapers and wrote innumerable articles. He was also a member of several scientific academies in Egypt and around the world.

Works

The author of "more than sixty books (including six novels) and 1,300 articles",[6] his major works include :

- Complete Works of Taha Hussein 1–16 [1]

- The Memory of Abu Al-Ala' al-ma'arri 1915

- Selected Poetical Texts of the Greek Drama 1924

Ibn Khaldun's Philosophy 1925- Dramas by a Group of the Most Famous French Writers 1924

- Pioneers of Thoughts 1925

- Wednesday Talk 1925

- Pre-Islamic Poetry jj

- Egyptian Childhood : The Autobiography of Taha Hussein 1928

- In the Summer 1933

- The Days "3 Volumes" 1933

- Hafez and Shawki 1933

- The Prophet's Life "Ala Hamesh El Sira" 1933

- Curlew's Prayers 1934

- From a Distance 1935

- Adeeb 1935

- The Literary Life in the Arabian Peninsula 1935

- Together with Abi El Alaa in his Prison 1935

- Poetry and Prose 1936

- Bewitched Palace 1937

- Together with El Motanabi 1937

The Future of Culture in Egypt 1938- Moments 1942

- The Voice of Paris 1943

- Sheherzad's Dreams 1943

- Tree of Misery 1944

- Paradise of Thorn 1945

- Chapters on Literature and Criticism 1945

- The Voice of Abu El Alaa 1945

- Osman "The first Part of the Greater Sedition

- "El Fitna Al Kubra" 1947

- Spring Journey 1948

- The Stream Of Days 1948

- The Tortured of Modern Conscience 1949

- The Divine Promise "El Wa'd El Haq" 1950

- The Paradise of Animals 1950

- The Lost Love 1951

- From There 1952

- Varieties 1952

- In The Midst 1952

- Ali and His Sons (The 2nd Part of the Greater Sedition) 1953

- (Sharh Lozoum Mala Yalzm, Abu El Alaa) 1955

- (Anatagonism and Reform 1955

- The Sufferers: Stories and Polemics (Published in Arabic in 1955), Translated by Mona El-Zayyat (1993), Published by The American University in Cairo, ISBN 9774242998

- Criticism and Reform 1956

- Our Contemporary Literature 1958

- Mirror of Islam 1959

- Summer Nonsense 1959

- On the Western Drama 1959

- Talks 1959

- Al-Shaikhan (Abi Bakr and Omar Ibn El Khatab) 1960

- From Summer Nonsense to Winter Seriousness 1961

- Reflections 1965

- Beyond the River 1975

- Words 1976

- Tradition and Renovation 1978

- Books and Author 1980

- From the Other Shore 1980

Translations

- Jules Simon's The Duty 1920–1921

- Athenians System (Nezam Al-Ethnien) 1921

- The Spirit of Pedagogy 1921

- Dramatic Tales 1924

- Andromaque (Racine) 1935

- From the Greek Dramatic Literature (Sophocle) 1939

- Voltaire's Zadig or (The Fate) 1947

- André Gide: From Greek

- Legends' Heroes

- Sophocle-Oedipe 1947.[1]

See also

Taha Hussein Museum – Historic house and biographical museum in Cairo- List of Egyptian authors

References

^ abc "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 10, 2004. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

^ Ghanayim, M. (1994). "Mahmud Amin al-Alim: Between Politics and Literary Criticism". Poetics Today. Poetics Today, Vol. 15, No. 2. 15 (2): 321–338. doi:10.2307/1773168. JSTOR 1773168.

^ "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

^ Labib Rizk, Dr Yunan. "A Diwan of contemporary life (391)". Ahram Weekly. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

^ Gershoni, I., J. Jankowski. (1987). Egypt, Islam, and the Arabs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ P. Cachia in Julie Scott Meisami & Paul Starkey, Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature, Volume 1, Taylor & Francis (1998), p. 297

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Taha Hussein |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taha Hussein. |