Epigallocatechin gallate

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP  | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

IUPAC name [(2R,3R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)chroman-3-yl] 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate | |

Preferred IUPAC name (2R,3R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-3-yl 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate | |

| Other names (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

ChEBI |

|

ChEMBL |

|

ChemSpider |

|

ECHA InfoCard | 100.111.017 |

IUPHAR/BPS |

|

MeSH | Epigallocatechin+gallate |

PubChem CID |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula | C22H18O11 |

Molar mass | 458.372 g/mol |

| Appearance | |

Solubility in water | soluble (33.3-100 g/L)[vague][1] |

Solubility | soluble in ethanol, DMSO, dimethyl formamide[1] at about 20 g/l[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Infobox references | |

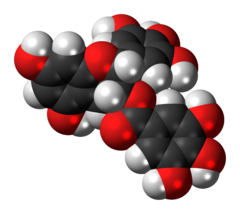

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), also known as epigallocatechin-3-gallate, is the ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid, and is a type of catechin.

EGCG, the most abundant catechin in tea, is a polyphenol under basic research for its potential to affect human health and disease. EGCG is used in many dietary supplements.

Contents

1 Food sources

1.1 Tea

1.2 Other

2 Bioavailability

3 Research

4 Potential toxicity

5 Regulation

6 See also

7 References

Food sources

Tea

It is found in high content in the dried leaves of green tea (7380 mg per 100 g), white tea (4245 mg per 100 g), and in smaller quantities, black tea (936 mg per 100 g).[3] During black tea production, the catechins are mostly converted to theaflavins and thearubigins via polyphenol oxidases.[which?][4]

Other

Trace amounts are found in apple skin, plums, onions, hazelnuts, pecans, and carob powder (at 109 mg per 100 g).[3]

Bioavailability

When taken orally, EGCG has poor absorption even at daily intake equivalent to 8–16 cups of green tea, an amount causing adverse effects such as nausea or heartburn.[5] After consumption, EGCG blood levels peak within 1.7 hours.[6] The absorbed plasma half-life is ~5 hours,[6] but with majority of unchanged EGCG excreted into urine over 0 to 8 hours.[6] Methylated metabolites appear to have longer half-lives and occur at 8-25 times the plasma levels of unmetabolized EGCG.[7]

Research

Well-studied in basic research, EGCG has various biological effects in laboratory studies.[8][9][10][11] A 2011 analysis by the European Food Safety Authority found that a cause and effect relationship could not be shown for a link between tea catechins and the maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentration.[12] A 2016 review found that high daily doses (107 to 856 mg/day) taken by human subjects over four to 14 weeks produced a small reduction of LDL cholesterol.[13]

Potential toxicity

A 2018 review showed that excessive intake of EGCG may cause liver toxicity.[14] In 2018, the European Food Safety Authority stated that daily intake of 800 mg or more could increase risk of liver damage.[15]

Regulation

Over 2008 to 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration issued several warning letters to manufacturers of dietary supplements containing EGCG for violations of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Most of these letters informed the companies that their promotional materials promoted EGCG-based dietary supplements the treatment or prevention of diseases or conditions that cause them to be classified as drugs under the United States code,[16][17][18] while another focused on inadequate quality assurance procedures and labeling violations.[19] The warnings were issued because the products had not been established as safe and effective for their marketed uses and were promoted as "new drugs", without approval as required under the Act.[18]

See also

- Epigallocatechin

- Health benefits of tea

- Theaflavin

- Tannin

- Phenolic content in tea

- Green tea extract

- List of phytochemicals in food

References

^ ab "(-)-Epigallocatechin gallate". Chemicalland21.com.

^ "Product Information: (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate" (PDF). Cayman Chemical. 4 September 2014.

^ ab Bhagwat, Seema; Haytowitz, David B.; Holden, Joanne M. (September 2011). USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3 (PDF) (Report). Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. pp. 2, 98–103. Retrieved 18 May 2015. CS1 maint: Date and year (link)

^ Lorenz, Mario; Urban, Janka; Engelhardt, Ulrich; Baumann, Gert; Stangl, Karl; Stangl, Verena (January 2009). "Green and Black Tea are Equally Potent Stimuli of NO Production and Vasodilation: New Insights into Tea Ingredients Involved". Basic Research in Cardiology. 104 (1): 100–110. doi:10.1007/s00395-008-0759-3. PMID 19101751. (Subscription required (help)).

^ Chow, H-H. Sherry; Cai, Yan; Hakim, Iman A.; Crowell, James A.; Shahi, Farah; Brooks, Chris A.; Dorr, Robert T.; Hara, Yukihiko; Alberts, David S. (15 August 2003). "Pharmacokinetics and safety of green tea polyphenols after multiple-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E in healthy individuals". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (9): 3312–3319. PMID 12960117.

^ abc Lee, Mao-Jung; Maliakal, Pius; Chen, Laishun; Meng, Xiaofeng; Bondoc, Flordeliza Y.; Prabhu, Saileta; Lambert, George; Mohr, Sandra; Yang, Chung S. (October 2002). "Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 11 (10 Pt 1): 1025–1032. PMID 12376503.

^ Manach, C; Williamson, G; Morand, C; Scalbert, A; Rémésy, C (January 2005). "Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 81 (1 Suppl): 230S–242S. PMID 15640486.

^ Fürst, Robert; Zündorf, Ilse (May 2014). "Plant-derived anti-inflammatory compounds: hopes and disappointments regarding the translation of preclinical knowledge into clinical progress". Mediators of Inflammation. 2014: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2014/146832. PMC 4060065 . PMID 24987194. 146832.

. PMID 24987194. 146832.

^ Granja, Andreia; Frias, Iúri; Neves, Ana Rute; Pinheiro, Marina; Reis, Salette (2017). "Therapeutic Potential of Epigallocatechin Gallate Nanodelivery Systems". BioMed Research International. 2017: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2017/5813793. ISSN 2314-6133.

^ Wu, Dayong; Wang, Junpeng; Pae, Munkyong; Meydani, Simin Nikbin (2012). "Green tea EGCG, T cells, and T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 33 (1): 107–118. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.001. ISSN 0098-2997.

^ Riegsecker, Sharayah; Wiczynski, Dustin; Kaplan, Mariana J.; Ahmed, Salahuddin (2013). "Potential benefits of green tea polyphenol EGCG in the prevention and treatment of vascular inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis". Life Sciences. 93 (8): 307–312. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.006. PMC 3768132 . PMID 23871988.

. PMID 23871988.

^ EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies) (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze (tea), including catechins in green tea, and improvement of endothelium-dependent vasodilation (ID 1106, 1310), maintenance of normal blood pressure". EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority. 9 (4): 2055. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2055.

^ Momose Y; et al. (2016). "Systematic review of green tea epigallocatechin gallate in reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of humans". Int J Food Sci Nutr. 67 (6): 606–13. doi:10.1080/09637486.2016.1196655. PMID 27324590. CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

^ Hu, J; Webster, D; Cao, J; Shao, A (2018). "The safety of green tea and green tea extracts consumption in adults - Results of a systematic review". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.03.019. PMID 29580974.

^ "Scientific opinion on the safety of green tea catechins". European Food Safety Authority. 18 April 2018. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5239. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

^ "Sharp Labs Inc: Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. Food and Drug Administration. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

^ "Fleminger Inc.: Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. Food and Drug Administration. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

^ ab "LifeVantage Corporation: Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. Food and Drug Administration. 17 April 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

^ "N.V.E. Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. Food and Drug Administration. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2017.