Tate Modern

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| |

Location within Central London | |

| Established | 2000 (2000) |

|---|---|

| Location | Bankside London, SE1 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°30′27″N 0°05′58″W / 51.5076°N 0.0994°W / 51.5076; -0.0994Coordinates: 51°30′27″N 0°05′58″W / 51.5076°N 0.0994°W / 51.5076; -0.0994 |

| Visitors | 5,656,004 (2017)[1]

|

| Director | Frances Morris |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | tate.org.uk/modern |

Tate Modern is a modern art gallery located in London. It is Britain's national gallery of international modern art and forms part of the Tate group (together with Tate Britain, Tate Liverpool, Tate St Ives and Tate Online).[2] It is based in the former Bankside Power Station, in the Bankside area of the London Borough of Southwark. Tate holds the national collection of British art from 1900 to the present day and international modern and contemporary art.[3] Tate Modern is one of the largest museums of modern and contemporary art in the world. As with the UK's other national galleries and museums, there is no admission charge for access to the collection displays, which take up the majority of the gallery space, while tickets must be purchased for the major temporary exhibitions. The gallery is London’s second most-visited attraction, behind the British Museum, pulling in approximately 5.5 million visitors annually.[4]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Bankside Power Station

1.2 Initial redevelopment

1.3 Opening and initial reception

1.4 Extension project

1.4.1 The Tanks

1.4.2 The Switch House

2 Galleries

3 Exhibitions

3.1 Collection exhibitions

3.1.1 History of the collection exhibitions

3.2 Temporary exhibitions

3.2.1 The Turbine Hall

3.2.2 Major temporary exhibitions

3.2.3 The Tanks

3.2.4 Project Space

3.2.5 Other areas

4 Other facilities

5 Access and environs

5.1 Transport connections

6 Directors

7 Controversies

7.1 Liberate Tate from BP

8 Selections from the permanent collection of paintings

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

History

Bankside Power Station

The Turbine Hall

Tate Modern is housed in the former Bankside Power Station, which was originally designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect of Battersea Power Station, and built in two stages between 1947 and 1963. It is directly across the river from St Paul's Cathedral. The power station closed in 1981.

Prior to redevelopment, the power station was a 200 m (660 ft) long, steel framed, brick clad building with a substantial central chimney standing 99 m (325 ft). The structure was roughly divided into three main areas each running east-west – the huge main Turbine Hall in the centre, with the boiler house to the north and the switch house to the south.

Initial redevelopment

For many years after closure Bankside Power station was at risk of being demolished by developers. Many people campaigned for the building to be saved and put forward suggestions for possible new uses. An application to list the building was refused. In April 1994 the Tate Gallery announced that Bankside would be the home for the new Tate Modern. In July of the same year, an international competition was launched to select an architect for the new gallery. Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron of Herzog & de Meuron were announced as the winning architects in January 1995. The £134 million conversion to the Tate Modern started in June 1995 and completed in January 2000.[5]

The most obvious external change was the two-story glass extension on one half of the roof. Much of the original internal structure remained, including the cavernous main turbine hall, which retained the overhead travelling crane. An electrical substation, taking up the Switch House in the southern third of the building, remained on-site and owned by the French power company EDF Energy while Tate took over the northern Boiler House for Tate Modern's main exhibition spaces.

Panoramic view from Tate Modern balcony

The history of the site as well as information about the conversion was the basis for a 2008 documentary Architects Herzog and de Meuron: Alchemy of Building & Tate Modern. This challenging conversion work was carried by Carillion.[5]

Opening and initial reception

Tate Modern was opened by the Queen on 11 May 2000.[6]

Tate Modern received 5.25 million visitors in its first year. The previous year the three existing Tate galleries had received 2.5 million visitors combined.[7]

Extension project

Tate Modern had attracted more visitors than originally expected and plans to expand it had been in preparation since 2004. These plans focused on the south west of the building with the intention of providing 5,000m2 of new display space, almost doubling the amount of display space.[8][9]

The southern third of the building was retained by the French power company EDF Energy as an electrical substation. In 2006, the company released the western half of this holding[10] and plans were made to replace the structure with a tower extension to the museum, initially planned to be completed in 2015. The tower was to be built over the old oil storage tanks, which would be converted to a performance art space. Structural, geotechnical, civil, and façade engineering and environmental consultancy was undertaken by Ramboll between 2008 and 2016.[11]

This project was initially costed at £215 million.[12] Of the money raised, £50 million came from the UK government; £7 million from the London Development Agency; £6 million from philanthropist John Studzinski; and donations from, among others, the Sultanate of Oman and Elisabeth Murdoch.[13]

In June 2013, international shipping and property magnate Eyal Ofer pledged £10m to the extension project, making it to 85% of the required funds. Eyal Ofer, chairman of London-based Zodiac Maritime Agencies, said the donation made through his family foundation would enable "an iconic institution to enhance the experience and accessibility of contemporary art".[14] The Tate director, Nicholas Serota, praised the donation saying it would help to make Tate Modern a "truly twenty-first-century museum".[15]

The Tanks

The first phase of the expansion involved the conversion of three large, circular, underground oil tanks originally used by the power station into accessible display spaces and facilities areas. These opened on 18 July 2012 and closed on 28 October 2012[7] as work on the tower building continued directly above. They reopened following the completion of the Switch House extension on 17 June 2016.

Two of the Tanks are used to show live performance art and installations while the third provides utility space.[16] Tate describes them as "the world's first museum galleries permanently dedicated to live art".[17]

The Switch House

Exterior of the Switch House

A ten-storey tower, 65 metres high from ground level, was built above the oil tanks.[18]

The original western half of the Switch House was demolished to make room for the tower and then rebuilt around it with large gallery spaces and access routes between the main building and the new tower on level 1 (ground level) and level 4. The new galleries on level 4 have natural top lighting. A bridge built across the turbine hall on level 4 to provides an upper access route.[8]

The new building opened to the public on 17 June 2016.[19]

The design, again by Herzog & de Meuron, has been controversial. It was originally designed with a glass stepped pyramid, but this was amended to incorporate a sloping façade in brick latticework (to match the original power-station building)[20] despite planning consent to the original design having been previously granted by the supervising authority.[21]

The extension provides 22,492 square metres of additional gross internal area for display and exhibition spaces, performance spaces, education facilities, offices, catering and retail facilities as well as a car parking and a new external public space.[22]

In May 2017 the Switch House was formally renamed the Blavatnik Building, after Anglo-Ukrainian billionaire Sir Leonard Blavatnik, who contributed a "substantial" amount of the £260m cost of the extension. Sir Nicholas Serota commented "Len Blavatnik's enthusiastic support ensured the successful realisation of the project and I am delighted that the new building now bears his name".[23]

Galleries

The collections in Tate Modern consist of works of international modern and contemporary art dating from 1900 until today.[24]

Levels 2, 3 and 4 contain gallery space. Each of those floors is split into a large east and west wing with at least 11 rooms in each. Space between these wings is also used for smaller galleries on levels 2 and 4. The Boiler House shows art from 1900 to the present day.[16]

The Switch House has eleven floors, numbered 0 to 10. Levels 0, 2, 3 and 4 contain gallery space. Level 0 consists of the Tanks, spaces converted from the power station's original fuel oil tanks, while all other levels are housed in the tower extension building constructed above them. The Switch House shows art from 1960 to the present day.[16]

The Turbine Hall is a single large space running the whole length of the building between the Boiler House and the Switch House. At six stories tall it represents the full height of the original power station building. It is cut by bridges between the Boiler House and the Switch House on levels 1 and 4 but the space is otherwise undivided. The western end consists of a gentle ramp down from the entrance and provides access to both sides on level 0. The eastern end provides a very large space that can be used to show exceptionally large artworks due its unusual height.

Exhibitions

Collection exhibitions

A gallery at Tate Modern.

The main collection displays consist of 8 areas with a named theme or subject. Within each area there are some rooms that change periodically showing different works in keeping with the overall theme or subject. The themes are changed less frequently. There is no admission charge for these areas.[25]

As of June 2016 the themed areas were:[16]

Start Display: A three-room display of works by major artists to introduce the basic ideas of modern art.- Artist and Society

- In The Studio

- Materials and Objects

- Media Networks

- Between Object and Architecture

- Performer and Participant

- Living Cities

There is also an area dedicated to displaying works from the Artist Rooms collection.

History of the collection exhibitions

Chimney of Tate Modern. The Swiss Light at its top was designed by Michael Craig-Martin and the architects Herzog & de Meuron and was sponsored by the Swiss government. It was dismantled in May 2008.

Since the Tate Modern first opened in 2000, the collections have not been displayed in chronological order but have been arranged thematically into broad groups. Prior to the opening of the Switch House there were four of these groupings at a time, each allocated a wing on levels 3 and 5 (now levels 2 and 4).

The initial hanging from 2000 to 2006:[26][27]

- History/Memory/Society

- Nude/Action/Body

- Landscape/Matter/Environment

- Still Life/Object/Real Life

The first rehang at Tate Modern opened in May 2006.[28][29] It eschewed the thematic groupings in favour of focusing on pivotal moments of twentieth-century art. It also introduced spaces for shorter exhibitions in between the wings. The layout was:

Material Gestures[30]

Poetry and Dream[31]

Energy and Process[32]

States of Flux[33]

In 2012 there was a partial third rehang.[34] The arrangement was:

Poetry and Dream[35]

Structure and Clarity[36]

Transformed Visions[37]- Energy and Process

Setting the Scene – A smaller section, located between wings, covering installations with theatrical or fictional themes.[38]

Temporary exhibitions

The Turbine Hall

Ólafur Elíasson, The Weather Project (2004)

Rachel Whiteread, EMBANKMENT (2005)

The Turbine hall, which once housed the electricity generators of the old power station, is five storeys tall with 3,400 square metres of floorspace.[39] It is used to display large specially-commissioned works by contemporary artists, between October and March each year.

From 2000 until 2012, the series was named after its corporate sponsor, Unilever. In this time the company provided £4.4m sponsorship in total including a renewal deal of £2.2m for a period of five years agreed in 2008.[40]

This series was planned to last the gallery's first five years, but the popularity of the series led to its extension until 2012.[41]

The artists who have exhibited commissioned work in the Turbine Hall as part of the Unilever series are:

| Date | Artist | Work(s) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 2000 – November 2000[42] | Louise Bourgeois | I Do, I Undo, I Redo | About |

| June 2001 – March 2002 | Juan Muñoz | Double Bind | About |

| October 2002 – April 2003 | Anish Kapoor | Marsyas | About |

| October 2003 – March 2004 | Olafur Eliasson | The Weather Project | About |

| October 2004 – May 2005 | Bruce Nauman | Raw Materials | About |

| October 2005 – May 2006 | Rachel Whiteread | EMBANKMENT | About |

| October 2006 – April 2007 | Carsten Höller | Test Site | About |

| October 2007 – April 2008 | Doris Salcedo | Shibboleth | About |

| October 2008 – April 2009 | Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster | TH.2058 | About |

| October 2009 – April 2010 | Miroslaw Balka | How It Is | About |

| October 2010 – April 2011 | Ai Weiwei | Sunflower Seeds | About |

| October 2011 – March 2012 | Tacita Dean | Film | About |

| July 2012 – October 2012 | Tino Sehgal | These associations | About |

In 2013, Tate Modern signed a sponsorship deal worth around £5 million with Hyundai to cover a ten-year program of commissions, then considered the largest amount of money ever provided to an individual gallery or museum in the United Kingdom.[43] The first commission for the Hyundai series is Mexican artist, Abraham Cruzvillegas.[44]

The artists who have exhibited commissioned work in the Turbine Hall as part of the Hyundai series thus far are:

| Date | Artist | Work(s) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 October 2015 – 3 April 2016[45] | Abraham Cruzvillegas | Empty Lot | About |

| 4 October 2016 – 2 April 2017[46] | Philippe Parreno | Title TK | About |

When there is no series running, the Turbine Hall is used for occasional events and exhibitions. In 2011 it was used to display Damien Hirst's For The Love of God.[47] A sell-out show by Kraftwerk in February 2013 crashed the ticket hotline and website, causing a backlash from the band's fans. In 2018 the Turbine Hall was used for two performances of Messiaen's Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum and Stockhausen's Gruppen.[48]

Major temporary exhibitions

Two wings of the Boiler House are used to stage the major temporary exhibitions for which an entry fee is charged. These exhibitions normally run for three or four months. When they were located on a single floor, the two exhibition areas could be combined to host a single exhibition. This was done for the Gilbert and George retrospective due to the size and number of the works.[49] Currently the two wings used are on level 3. It is not known if this arrangement is permanent. Each major exhibition has a dedicated mini-shop selling books and merchandise relevant to the exhibition.

A 2014 show of Henri Matisse provided Tate Modern with London's best-attended charging exhibition, and with a record 562,622 visitors overall, helped by a nearly five-month-long run.[50] In 2018, Joan Jonas had a retrospective exhibition.[51]

The Tanks

The Tanks, located on level 0, are three large underground oil tanks, connecting spaces and side rooms originally used by the power station and refurbished for use by the gallery. One tank is used to display installation and video art specially commissioned for the space while smaller areas are used to show installation and video art from the collection. The Tanks have also been used as a venue for live music.[52]

Project Space

The Project Space (formerly known as the Level 2 Gallery) was a smaller gallery located on the north side of the Boiler House on level 1 which housed exhibitions of contemporary art in collaboration with other international art organisations. Its exhibitions typically ran for 2–3 months and then travelled to the collaborating institution for display there. The space was only accessible by leaving the building and re-entering using a dedicated entrance. It is no longer used as gallery space.

Other areas

Works are also sometimes shown in the restaurants and members' rooms. Other locations that have been used in the past include the mezzanine on Level 1 and the north facing exterior of the Boiler House building.[53]

Other facilities

In addition to exhibition space there are a number of other facilities:

- A large performance space in one of the tanks on level 0 used to show a changing programme of performance works for which there is sometimes an entrance charge.

- The Starr Auditorium and a seminar room on level 1 which are used to show films and host events for which there is usually an entrance charge.

- The Clore Education Centre, Clore Information Room and McAulay Studios on level 0 which are facilities for use by visiting educational institutions.

- One large and several small shops selling books, prints and merchandise.

- A cafe, an espresso bar, a restaurant and bar and a members' room.

- Tate Modern community garden, co-managed with Bankside Open Spaces Trust

Access and environs

Tate Modern on the opening day of the Millennium Bridge in 2000

The closest station is Blackfriars via its new south entrance. Other nearby stations include Southwark, as well as St Paul's and Mansion House north of the river which can be reached via the Millennium Bridge. The lampposts between Southwark tube station and Tate Modern are painted orange to show pedestrian visitors the route.

There is also a riverboat pier just outside the gallery called Bankside Pier, with connections to the Docklands and Greenwich via regular passenger boat services (commuter service) and the Tate to Tate service, which connects Tate Modern with Tate Britain.

To the west of Tate Modern lie the sleek stone and glass Ludgate House, the former headquarters of Express Newspapers and Sampson House, a massive late Brutalist office building.

Transport connections

| Service | Station/Stop | Lines/Routes served | Distance from Tate Modern |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Buses | Southwark Street / Blackfriars Road | RV1 | 0.2-mile walk[54] |

| Blackfriars Bridge | 381, N343, N381 | 0.2-mile walk[55] | |

| Blackfriars Bridge / South Side | 45, 63, 100, N63, N89 | 0.2-mile walk[56] | |

| Southwark Bridge / Bankside Pier | 344 | 0.4-mile walk[57] | |

| London Underground | Southwark | 0.4-mile walk[58] | |

| National Rail | Blackfriars | Thameslink, Southeastern | 0.5-mile walk[59] |

London Bridge | Thameslink, Southern, Southeastern | 0.7-mile walk[60] | |

| London River Services | Bankside Pier | Commuter Service Tate to Tate Westminster to St Katharine's Circular |

- At the exit of Southwark tube station, orange lamposts direct visitors to Tate Modern.

Directors

Frances Morris' appointment as director was announced in January 2016.[61]

Lars Nittve (1998–2001)

Vicente Todolí (2003–2010)

Chris Dercon (2010–2016)

Frances Morris (2016–)

Controversies

Liberate Tate from BP

Since 2010 there have been 14 protest art performances by the art collective Liberate Tate demanding the Tate to "disengage from BP as a sponsor, and stop allowing Tate to be used to deflect attention away from the devastating impacts that BP has around the world." BP is criticised for operations in relation with Petroleum exploration in the Arctic, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Oil sands and climate change. The artists involved in the protests are referring to a deal between BP and the Tate: BP pays £224,000 a year to the Tate. The Tate presents the brand BP in return. In June 2015 a group of artists occupied Tate Modern for 25 hours.[62][63]

Selections from the permanent collection of paintings

Albert Gleizes, 1911, Portrait de Jacques Nayral, oil on canvas, 161.9 x 114 cm. This painting was reproduced in Fantasio: published 15 October 1911, for the occasion of the Salon d'Automne where it was exhibited the same year.

Georges Braque, 1909–10, La guitare (Mandora, La Mandore), oil on canvas, 71.1 x 55.9 cm

Pablo Picasso, 1909–10, Figure dans un Fauteuil (Seated Nude, Femme nue assise), oil on canvas, 92.1 x 73 cm. This painting from the collection of Wilhelm Uhde was confiscated by the French state and sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921

Robert Delaunay, 1912, Windows Open Simultaneously (First Part, Third Motif), oil on canvas, 45.7 x 37.5 cm

Juan Gris, 1914, The Sunblind, collage and oil on canvas, 92 × 72.5 cm

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1909/1926, Badende bei Moritzburg (Bathers at Moritzburg)

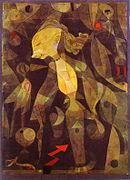

Paul Klee, 1921, Abenteuer eines Fräuleins (A Young Lady's Adventure), watercolor on paper, 43.8 × 30.8 cm

Paul Klee, 1935, Walpurgisnacht (Walpurgian Night)

Robert Delaunay, 1934, Endless Rhythm

See also

- List of most visited art museums

- List of museums in London

References

^ ab "2017 Visitor Figures". Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Retrieved 22 March 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "History and development Tate On-line". Tate Etc. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "About". Tate Etc. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Alex Landon (14 Feb 2019). "Modern art finds its spiritual home at Tate Modern". Secret London.

^ ab "Tate Modern builders Carillion win £400m Battersea Power Station contract". Your local Guardian. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

^ "2000: Sneak preview of new Tate Modern". BBC. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

^ ab "Tate Modern. Nought to Sixteen. A History". Art Review. 2016.

^ ab Tate Guide, August–September 2012

^ "Vision". Tate Etc. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

^ Riding, Alan (26 July 2006). "Tate Modern Announces Plans for an Annex". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

^ "Tate Modern extension". Retrieved 22 February 2017.

^ Tate Modern's chaotic pyramid, The Times, 26 July 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

^ Farah Nayeri (20 April 2012), Murdoch’s Daughter Elisabeth Gives Tate at Least $1.6 MlnBloomberg.

^ Pickford, James (2 July 2013). "Eyal Ofer donates £10m to Tate Modern extension". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

^ Mark Brown, arts correspondent (2 July 2013). "Tate Modern receives £10m gift from Israeli shipping magnate Eyal Ofer | Art and design". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

^ abcd Tate Modern Visitor Map June 2016

^ "The Tanks: Art in Action". Tate Etc. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Environmental Statement non-technical summary". Tate Etc. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

^ "The new Tate Modern opening weekend – Special Event at Tate Modern". Tate Etc. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

^ "Tate Modern extension redesigned". Worldarchitecturenews.com. 18 July 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Tate Modern extension, Bankside" (PDF). Greater London Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

^ "Tate Modern extension by Herzog & de Meuron architects". Inexhibit. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

^ Hannah Ellis-Petersen. "Tate Modern names extension after billionaire Len Blavatnik | Art and design". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

^ "Tate Modern". Retrieved 22 January 2016.

^ Tate. "Tate Modern".

^ "Tate Modern: Collection 2000 – Tate".

^ "Tate Modern: Collection 2003 – Tate".

^ "Tate Modern launches first major rehang of its Collection with the support of UBS – Tate".

^ Foundation, Internet Memory. "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 16 March 2008.

^ Foundation, Internet Memory. "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 16 March 2008.

^ Foundation, Internet Memory. "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 16 March 2008.

^ Foundation, Internet Memory. "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 4 January 2010.

^ Foundation, Internet Memory. "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 26 September 2008.

^ "Collection Displays". Tate Etc. 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Foundation, Internet Memory. "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive – The National Archives". Archived from the original on 1 August 2011.

^ "Structure and Clarity". Tate Etc. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Transformed Visions". Tate Etc. 23 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

^ "Setting the Scene". Tate Etc. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Brooks, Xan (7 October 2005). "Profile: Rachel Whiteread". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 April 2006.

^ Gareth Harris (14 August 2012), Tate seeks new sponsor for Turbine Hall commissions Archived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

^ "Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster Chosen for Tate Modern's Turbine Hall". Retrieved 16 September 2008.

^ "The Unilever Series". Tate Etc. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ xMartin Bailey (20 January 2014), Tate signs £5m sponsorship with Hyundai Archived 22 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

^ "Hyundai Commission 2015: Abraham Cruzvillegas". Retrieved 23 January 2015.

^ "Hyundai Commission 2015". Tate Etc. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

^ "Hyundai Commission 2016". Tate Etc. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

^ "Damien Hirst's iconic For the Love of God to be shown in Tate Modern's Turbine Hall". Tate Etc. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

^ "Stockhausen London Symphony Orchestra at Tate Modern". Retrieved 1 January 2019.

^ "Gilbert & George – Tate". Retrieved 22 January 2016.

^ Javier Pes and Emily Sharpe (2 April 2015), Visitor figures 2014: the world goes dotty over Yayoi Kusama Archived 20 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

^ "Joan Jonas review – post-internet confusion before the internet". The Guardian. 13 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

^ "Proms at ... The Tanks at Tate Modern". BBC. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

^ "Street Art – Tate". Retrieved 22 January 2016.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from Southwark Street / Blackfriars Road bus stop" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from Blackfriars Bridge bus stop" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from Blackfriars Bridge / South Side bus stop" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from Southwark Bridge / Bankside Pier bus stop" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from Southwark tube station" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from Blackfriars station" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Google (28 February 2012). "Walking directions to Tate Modern from London Bridge station" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

^ Jonathan Jones. "Why it's great news that Frances Morris will run Tate Modern". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

^ The Guardian, Climate activists leave Tate Modern after all-night protest against BP

^ '’Liberate Tate'’

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Larsen, Reif (July 18, 2017). "The Tate Modern and the Battle for London's Soul". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Temporary Exhibitions at Tate Modern – 2008 to 2016, Dataset, doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.5766570.v1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tate Modern. |

Official website

'Tate Modern: a Year of Sweet Success' by Esther Leslie, in Radical Philosophy- The buildings of Bankside Power Station(Tate Modern) and Battersea Power Station compared

Inside Bankside Power Station with Antony Gormley 1991 on YouTube- Extension project description