Oracle bone script

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Oracle bone script .mw-parser-output .noboldfont-weight:normal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Logographic |

| Languages | Old Chinese |

Time period | Bronze Age China |

Child systems | Chinese characters |

Oracle bone script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 甲骨文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | "Shell-and-bone script" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oracle bone script (Chinese: 甲骨文) was the form of Chinese characters used on oracle bones—animal bones or turtle plastrons used in pyromantic divination—in the late 2nd millennium BCE, and is the earliest known form of Chinese writing. The vast majority[a] were found at the Yinxu site (in modern Anyang, Henan Province). They record pyromantic divinations of the last nine kings of the Shang dynasty, beginning with Wu Ding, whose accession is dated by different scholars at 1250 BCE or 1200 BCE.[1][2] After the Shang were overthrown by the Zhou dynasty in c. 1046 BCE, divining with milfoil became more common, and very few oracle bone writings date from the early Zhou.[3]

The late Shang oracle bone writings, along with a few contemporary characters in a different style cast in bronzes, constitute the earliest[4] significant corpus of Chinese writing, which is essential for the study of Chinese etymology, as Shang writing is directly ancestral to the modern Chinese script. It is also the oldest known member and ancestor of the Chinese family of scripts, preceding the bronzeware script.

Contents

1 Name

2 Precursors

3 Style

4 Structure and function

5 Zhou dynasty oracle bones

6 Scholarship

7 Computer encoding

8 Samples

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

11.1 Citations

11.2 Bibliography

12 External links

Name

The common Chinese term for the script is jiǎgǔwén (甲骨文 "shell and bone script"). It is an abbreviation of guījiǎ shòugǔ wénzì (龜甲獸骨文字 "tortoise-shell and animal-bone script"), which appeared in the 1930s as a translation of the English term "inscriptions upon bone and tortoise shell" first used by the American missionary Frank H. Chalfant (1862–1914) in his 1906 book Early Chinese Writing.[5][6]

In earlier decades, Chinese authors used a variety of names for the inscriptions and the script, based on the place they were found (Yinxu), their purpose (bǔ 卜 "to divine") or the method of writing (qì 契 "to engrave").[5]

As the majority of oracle bones bearing writing date from the late Shang dynasty, oracle bone script essentially refers to a Shang script.

Precursors

It is certain that Shang-lineage writing underwent a period of development before the Anyang oracle bone script because of its mature nature.[b] However, no significant quantity of clearly identifiable writing from before or during the early to middle Shang cultural period has been discovered. The few Neolithic symbols found on pottery, jade, or bone at a variety of cultural sites in China are very controversial, and there is no consensus that any of them are directly related to the Shang oracle bone script.[7]

Style

Shang oracle bone script: 虎 hǔ 'tiger'

Comparison of Shang bronzeware script, oracle bone script, and regular script characters

Shang oracle bone script: 目 mù 'eye'

The oracle bone script of the late Shang appears pictographic, as does its contemporary, the Shang writing on bronzes. The earliest oracle bone script appears even more so than examples from late in the period (thus some evolution did occur over the roughly 200-year period).[8] Comparing oracle bone script to both Shang and early Western Zhou period writing on bronzes, oracle bone script is clearly greatly simplified, and rounded forms are often converted to rectilinear ones; this is thought to be due to the difficulty of engraving the hard, bony surfaces, compared with the ease of writing them in the wet clay of the molds the bronzes were cast from. The more detailed and more pictorial style of the bronze graphs is thus thought to be more representative of typical Shang writing (as would have normally occurred on bamboo books) than the oracle bone script forms, and this typical style continued to evolve into the Zhou period writing and then into the seal script of the Qin in the late Zhou period.

It is known that the Shang people also wrote with brush and ink, as brush-written graphs have been found on a small number of pottery, shell and bone, and jade and other stone items,[9] and there is evidence that they also wrote on bamboo (or wooden) books[c] just like those found from the late Zhou to Hàn periods, because the graphs for a writing brush (聿 yù, depicting a hand holding a writing brush[d]) and bamboo book (冊 cè, a book of thin vertical slats or slips with horizontal string binding, like a Venetian blind turned 90 degrees) are present in the oracle bone script.[9][10][e] Since the ease of writing with a brush is even greater than that of writing with a stylus in wet clay, it is assumed that the style and structure of Shang graphs on bamboo were similar to those on bronzes, and also that the majority[9][10] of writing occurred with a brush on such books. Additional support for this notion includes the reorientation of some graphs,[f] by turning them 90 degrees as if to better fit on tall, narrow slats; this style must have developed on bamboo or wood slat books and then carried over to the oracle bone script.

Additionally, the writing of characters in vertical columns, from top to bottom, is for the most part carried over from the bamboo books to oracle bone inscriptions.[11] In some instances lines are written horizontally so as to match the text to divinatory cracks, or columns of text rotate 90 degrees in mid stream, but these are exceptions to the normal pattern of writing,[12] and inscriptions were never read bottom to top.[13] The vertical columns of text in Chinese writing are traditionally ordered from right to left; this pattern is found on bronze inscriptions from the Shang dynasty onward. Oracle bone inscriptions, however, are often arranged so that the columns begin near the centerline of the shell or bone, and move toward the edge, such that the two sides are ordered in mirror-image fashion.[11]

Structure and function

Despite the pictorial nature of the oracle bone script, it was a fully functional and mature writing system by the time of the Shang dynasty,[14] i.e., able to record the Old Chinese language in its entirety and not just isolated kinds of meaning. This level of maturity clearly implies an earlier period of development of at least several hundred years.[g] From their presumed origins as pictographs and signs, by the Shang dynasty, most graphs were already conventionalized[15] in such a simplified fashion that the meanings of many of the pictographs are not immediately apparent. Compare, for instance, the third and fourth graphs in the row below. Without careful research to compare these to later forms, one would probably not know that these represented 豕 shĭ "swine" and 犬 quǎn "dog" respectively. As Boltz (1994 & 2003 p. 31–33) notes, most of the oracle bone graphs are not depicted realistically enough for those who do not already know the script to recognize what they stand for; although pictographic in origin they are no longer pictographs in function. Boltz instead calls them zodiographs (p. 33), reminding us that functionally they represent words, and only through the words do they represent concepts, while for similar reasons Qiu labels them semantographs.

By the late Shang oracle bone script, the graphs had already evolved into a variety of mostly non-pictographic functions[citation needed], including all the major types of Chinese characters now in use. Phonetic loan graphs, semantic-phonetic compounds, and associative compounds were already common. One structural and functional analysis of the oracle bone characters found that they were 23% pictographs, 2% simple indicatives, 32% associative compounds, 11% phonetic loans, 27% phonetic-semantic compounds, and 6% uncertain.[h]

Although it was a fully functional writing system, the oracle bone script was not fully standardized. By the early Western Zhou period, these traits had vanished, but in both periods, the script was not highly regular or standardized; variant forms of graphs abound, and the size and orientation of graphs is also irregular. A graph when inverted horizontally generally refers to the same word, and additional components are sometimes present without changing the meaning. These irregularities persisted until the standardization of the seal script in the Qin dynasty.

Comparison of oracle bone script, large and small seal scripts, and regular script characters for autumn (秋)

Of the thousands of characters found from all the bone fragments so far, the majority still remain undeciphered. One reason for this is that components of certain oracle bone script characters may differ in later script forms. Such differences may be accounted for by character simplification and/or by later generations misunderstanding the original graph, which had evolved beyond recognition. For instance, the standard character for ‘autumn’ (秋) now appears with 禾 ('plant stalk') as one component and 火 ('fire') as another component, whereas the oracle bone script form of the character depicts an insect-like figure with antennae - either a cricket[16] or a locust - with a variant depicting fire ![]() below said figure. In this case, the modern character is a simplification of an archaic variant 𪛁 (or 𥤚)[17] which is closer to the oracle bone script form - albeit with the insect figure being confused with the similar-looking character for 'turtle' (龜) and the addition of the 禾 component. (Another rarer simplification of 𪛁 is 龝, with 龜 instead of 火).

below said figure. In this case, the modern character is a simplification of an archaic variant 𪛁 (or 𥤚)[17] which is closer to the oracle bone script form - albeit with the insect figure being confused with the similar-looking character for 'turtle' (龜) and the addition of the 禾 component. (Another rarer simplification of 𪛁 is 龝, with 龜 instead of 火).

Another reason is that some characters exist only in oracle bone script, dropping out of later usage (usually being replaced in their duties by other, newer characters). In such cases, context - when available - may be used to determine the possible meaning of the character. One good example is shown in the fragment below, labeled "oracle bone script for Spring". The top left character in this image has no known modern Chinese counterpart. One of the better known characters however is shown directly beneath it looking like an upright isosceles triangle with a line cutting through the upper portion. This ![]() is the oracle bone script character for 王 wáng ("king").

is the oracle bone script character for 王 wáng ("king").

Zhou dynasty oracle bones

Hand copy of a Zhou inscription[18][19]

The numbers of oracle bones with inscriptions contemporaneous with the end of Shang and the beginning of Zhou is relatively few in number compared with the entire corpus of Shang inscriptions. Until 1977, only a few inscribed shell and bone artifacts were known. Zhou related inscriptions have been unearthed since the 1950s, with find fragments having only one or two characters. In August 1977, a large hoard of several thousand pieces was discovered in an area closely related to the heartland of the ancient Zhou. Of these, only two or three hundred items were inscribed.

Scholarship

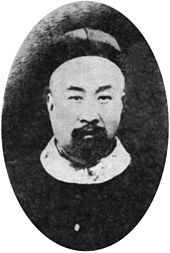

Wang Yirong, Chinese politician and scholar, was the first to recognize the oracle bone inscriptions as ancient writing.

Among the major scholars making significant contributions to the study of the oracle bone writings, especially early on, were:[20]

Wang Yirong recognized the characters as being ancient Chinese writing in 1899.

Liu E collected five thousand oracle bone fragments, published the first volume of examples and rubbings in 1903, and correctly identified thirty-four characters.

Sun Yirang was the first serious researcher of oracle bones.

Luo Zhenyu collected over 30,000 oracle bones and published several volumes, identified the names of the Shang kings, and thus positively identified the oracle bones as being artifacts from the Shang reign.

Wang Guowei demonstrated that the commemorative cycle of the Shang kings matched the list of kings in Sima Qian's Records of the Historian.

Dong Zuobin identified the diviners and established a chronology for the oracle bones as well as numerous other dating criteria.

Guo Moruo editor of the Heji, the largest published collection of oracle bones.

Ken-ichi Takashima, first scholar to systematically treat the language of the oracle bones from the perspective of modern linguistics.

Computer encoding

A proposal to include oracle bone script in Unicode is being prepared.[21]Codepoints in Unicode Plane 3 (the Tertiary Ideographic Plane) have been tentatively allocated.[22]

Samples

An oracle bone (which is incomplete) with a diviner asking the Shang king if there would be misfortune over the next ten days

Tortoise plastron with divination inscription dating to the reign of King Wu Ding

Oracle script from a divining

Oracle script inquiry about rain: "Today, will it rain?"

Oracle script inquiry about rain (annotated)

Oracle script for Spring

Oracle script for Autumn

Oracle script for Winter

豕 shĭ 'swine'

犬 quǎn 'dog'

See also

Mojikyo – Software developed by Mojikyo researchers that includes a set of oracle bone characters.- Chinese family of scripts

Notes

^ A few such shells and bones do not record divinations, but bear other records such as those of hunting trips, records of sacrifices, wars or other events (Xu Yahui. 許雅惠. 2002, p. 34. (in Chinese)), calendars (Xu Yahui p. 31), or practice inscriptions; these are termed shell and bone inscriptions, rather than oracle bones, because no oracle (divination) was involved. However, they are still written in oracle bone script.

^ For example, many characters had already undergone extensive simplification and linearization; the processes of semantic extension and phonetic loan had also clearly been at work for some time, at least hundreds of years and perhaps longer.

^ There are no such bamboo books extant before the late Zhou, however, as the materials were not permanent enough to survive.

^ The modern word 筆 bĭ is derived from a Qin dialectal variant of this word (Baxter & Sagart 2014:42–43).

^ As Qiu 2000 p.62–3 notes, the Shàngshū’s Duōshì chapter also refers to use of such books by the Shang.

^ Identification of these graphs is based on consultation of Zhao Cheng (趙誠, 1988), Liu Xinglong (劉興隆, 1997), Wu, Teresa L. (1990), Keightley, David N. (1978 & 2000), and Qiu Xigui (2000).

^ Boltz surmises that the Chinese script was invented around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE, i.e. very roughly ca. 1500 BCE, in the early Shang, and based on the currently available evidence declares attempts to push this date earlier "unsubstantiated speculation and wishful thinking". (1994 & 2003, p.39)

^ Li Xiaoding (李孝定) 1968 p.95, cited in Woon 1987; the percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding; see Chinese character classification for explanations of the various types listed here.

References

Citations

^ Li, Xueqin (2002). "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4: 321–333. doi:10.1163/156852302322454585..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Keightley 1978, p. 228

^ Nylan, Michael (2001). The five "Confucian" classics, p. 217

^ Boltz (1994 & 2003), p.31

^ ab Wilkinson (2015), p. 681.

^ Chalfant, Frank H. (1906). Early Chinese Writing. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute. p. 30.

^ Qiu Xigui 裘錫圭 (2000).

^ Qiu 2000, p.64

^ abc Qiu 2000, p.63

^ ab Xu Yahui, p.12

^ ab Keightley 1978, p.50

^ Qiu 2000, p.67; Keightley 1978, p.50

^ Keightley 1978, p.53

^ Boltz (1994 & 2003), p.31; Qiu Xigui 2000, p.29

^ Boltz (1994 & 2003), p.55

^ "秋 in Multi-function Chinese Character Database (漢語多功能字庫)".

^ Shuowen Jiezi entry for 秋 (秌): 从禾,省聲。𪛁,籒文不省。

^ p. 67, Liu Xiang et al. 商周古文字读本, Yuwen Pub.,

ISBN 7-80006-238-4.

^ p. 327 Gao Ming, 中国古文字学通论, Beijing University Press,

ISBN 7-301-02285-9

^ Xu Yahui, p.16–19

^ "L2/15-280: Request for comment on encoding Oracle Bone Script" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC. 2015-10-21. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

^ "Roadmap to the TIP". Unicode Consortium. 2016-01-21. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Boltz, William G. (1994; revised 2003). The Origin and Early Development of the Chinese Writing System. American Oriental Series, vol. 78. American Oriental Society, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

ISBN 0-940490-18-8 - Chen Zhaorong 陳昭容. (2003) Qinxi wenzi yanjiu: Cong hanzi-shi de jiaodu kaocha 秦系文字研究 ﹕从漢字史的角度考察 (Research on the Qin (Ch'in) Lineage of Writing: An Examination from the Perspective of the History of Chinese Writing). Taipei: Academia Sinica, Institute of History and Philology Monograph.

ISBN 957-671-995-X. - Gao Ming 高明 (1996). Zhongguo Guwenzi Xuetonglun 中国古文字学通论. Beijing: Beijing University Press.

ISBN 7-301-02285-9

Keightley, David N. (1978). Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China. University of California Press, Berkeley. Large format hardcover,

ISBN 0-520-02969-0 (out of print); A 1985 ppbk 2nd edition also printed,

ISBN 0-520-05455-5.- Keightley, David N. (2000). The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.). China Research Monograph 53, Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California – Berkeley.

ISBN 1-55729-070-9, ppbk. - Liu Xiang 刘翔 et al., (1989, 3rd reprint 1996). Shang-zhou guwenzi duben 商周古文字读本 (Reader of Shang-Zhou Ancient Characters). Yuwen Publishers.

ISBN 7-80006-238-4

Qiu Xigui Chinese Writing (2000). Translation by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

ISBN 1-55729-071-7.- Thorp, Robert L. "The Date of Tomb 5 at Yinxu, Anyang: A Review Article," Artibus Asiae (Volume 43, Number 3, 1981): 239–246.

Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual (4th ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-08846-7.- Xu Yahui 許雅惠 (2002). Ancient Chinese Writing, Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Ruins of Yin. Illustrated guide to the Special Exhibition of Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. English translation by Mark Caltonhill and Jeff Moser. National Palace Museum, Taipei. Govt. Publ. No. 1009100250.

- Zhao Cheng 趙誠 (1988). Jiǎgǔwén Jiǎnmíng Cídiǎn – Bǔcí Fēnlèi Dúbĕn 甲骨文簡明詞典 – 卜辭分類讀本. Beijing: Zhōnghúa Shūjú,

ISBN 7-101-00254-4/H•22 (in Chinese)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oracle bone script. |

More on Oracle Bone Script, at BeyondCalligraphy.com

Luo, Zhenyu (1912). Yīnxū shūqì 殷虛書契 [Yinxu inscriptions].

Menzies, James Mellon (1917). Oracle records from the Waste of Yin. Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh.