Saturiwa

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

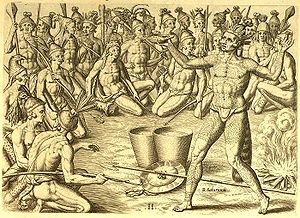

One of Theodor de Bry's engravings, supposedly based on drawings by Jacques LeMoyne, depicting Chief Saturiwa preparing his men for battle | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Extinct as tribe | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| North Florida around the mouth of the St. Johns River (present-day Jacksonville) | |

| Languages | |

Timucuan language, Mocama dialect | |

| Religion | |

| Native | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Timucua |

The Saturiwa were a Timucua chiefdom centered on the mouth of the St. Johns River in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. They were the largest and best attested chiefdom of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of present-day northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. They were a prominent political force in the early days of European settlement in Florida, forging friendly relations with the French Huguenot settlers at Fort Caroline in 1564 and later becoming heavily involved in the Spanish mission system.

The Saturiwa are so called after their chief at the time of contact with the Europeans, Saturiwa. At that time the chief's main village was located on the south bank of the St. Johns River, and he was sovereign over thirty other chiefs and their villages. Chief Saturiwa allied with the French, who built Fort Caroline in Saturiwa territory, and later aided them against the Spanish of St. Augustine. After the French were dislodged from Florida, the Saturiwa made peace with the Spanish, who established Mission San Juan del Puerto near their main village. Like other Florida native peoples, the Saturiwa were decimated by new infectious diseases and warfare through the 17th century. They disappear from the historical record by the start of the 18th century; surviving Saturiwa likely merged with other Timucua and lost their independent identity.[1]

Contents

1 Area

2 History

3 Notes

4 References

Area

The main village of the Saturiwa was located in present-day Jacksonville, Florida, on the south bank of the St. Johns River, near its mouth. According to the French records, Chief Saturiwa was the sovereign over thirty other village chiefs, ten of whom were his "brothers".[2] The villages of Saturiwa's alliance were concentrated around the mouth of the St. Johns River, and were dispersed upriver and along the adjacent Atlantic coast from St. Augustine north to the St. Marys River, at the border of present-day Georgia.[3] Up the St. Johns to the west, toward present-day downtown Jacksonville, were the villages of Omoloa, Casti, and Malica. The northern extent of Saturiwa's authority was the village of Caravay or Sarabay, possibly on Little Talbot Island. Another village, Alimacani, was located on Fort George Island across the river from the main village.[4] There were additional villages located along the coast to the south, including Seloy, which later became the site of the Spanish colony of St. Augustine.[5]

To the north of the Saturiwa were other Mocama-speaking peoples, including the Tacatacuru. The Tacatacuru's main village was on Cumberland Island in what is now Georgia, and they evidently controlled other villages on the coast.[4] Farther up the river to the southwest, in an area extending from roughly Palatka to Lake George, were the Utina, another Timucua group who were often at war with the Saturiwa.[6] The area between Jacksonville and Palatka was relatively less populated; it is possible that this region served as a buffer between the Saturiwa and the Utina.[6]

History

The history of the Saturiwa prior to contact with Europeans is obscure. The area had been inhabited by indigenous peoples for thousands of years; there is evidence of pottery dating to 2500 BC.[7] Like other Mocama, the Saturiwa participated in the Savannah archaeological culture,[8] and also the St. Johns culture.[9]

Athore, son of the Timucuan king Saturiwa, showing Laudonnière the monument placed by Jean Ribault.

The Saturiwa met the French Huguenot expedition under Jean Ribault when it explored the area in 1562, though the French did not record any name for them at that time.[1] Two years later, the Saturiwa again met the French when they returned to the area to found Fort Caroline.[1]

Chief Saturiwa forged friendly relations with the French settlers, trading and exchanging gifts with the newcomers and allowing them to establish Fort Caroline in his territory.[1] He offered to assist in the construction of the fort; the colony's governor, René Goulaine de Laudonnière took up the offer, and the Saturiwa provided a palm-thatched roof for the barn. Saturiwa intended for this pact of friendship to compel Laudonnière to aid him against his enemies, the Utina, who lived upriver to the southwest. Laudonnière, however, refused to join an assault against the powerful Utina, which soured relations between the two parties. The French eventually repaired the relationship with the Saturiwa, but in 1565 Fort Caroline was sacked by Spanish forces under Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who had recently founded St. Augustine.

The Saturiwa initially resisted the Spanish. In 1566 they joined the Potano and Mayaca against the Agua Dulce and their Spanish allies. In 1567 the Saturiwa, together with the Tacatacuru and others, aided Dominique de Gourgue in an assault on Spanish-held Fort Caroline. Eventually, however, the Saturiwa submitted to the Spanish, who founded some of their first missions in Florida in their territory. The principal mission of the Saturiwa was San Juan del Puerto, located near Alicamani on Fort George Island, where Francisco Pareja undertook his works on the Timucua language.[1]

The Saturiwa became the primary tribe in the Spanish mission system, but their fortunes declined markedly through the 17th century. By 1601, they were subject to the head chief of "San Pedro" (Tacatacuru), according to Spanish records.[10] They were severely affected by outbreaks of disease that wracked Florida in 1617 and again in 1672. Their missions are mentioned in lists in 1675 and 1680, though the lists indicate a dwindling population. After this they disappear from the record. It is likely that any surviving Saturiwa merged with other Timucua groups, and lost their independent identity.[1]

Notes

^ abcdef Swanton, pp. 138–139.

^ Milanich, p. 48.

^ Deagan 1978

^ ab Milanich, p. 49.

^ Hann, p. 38–39.

^ ab Milanich, p. 53.

^ Soergel, Matt (18 Oct 2009). "The Mocama: New name for an old people". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved May 12, 2010..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Milanich, p. 51.

^ Worth, p. 20–21.

^ Deagan, p. 91.

References

- Deagan, Kathleen A. (1978). "Cultures in Transition: Fusion and Assimilation among the Eastern Timucua." In Jerald Milanich and Samuel Procter, eds. Tacachale: Essays on the Indians of Florida and southeastern Georgia during the Historic Period. The University Presses of Florida.

ISBN 0-8130-0535-3 - Hann, John H. (1996) A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. University Press of Florida.

ISBN 0-8130-1424-7

Laudonnière, René; Bennett, Charles E. (Ed.) (2001). Three Voyages. University of Alabama Press.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Milanich, Jerald (1999). The Timucua. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-21864-5. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

Swanton, John Reed (2003). The Indian tribes of North America. Genealogical Publishing. ISBN 0-8063-1730-2. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

Worth, John E. (1998). Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida. Volume 1: Assimilation. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1574-X. Retrieved June 13, 2010.