Funk

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| Funk | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Mid-1960s,[1] United States |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Derivative forms |

|

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Fusion genres | |

| |

| Regional scenes | |

| United States | |

| Other topics | |

| |

Funk is a music genre that originated in African-American communities in the mid-1960s when African-American musicians created a rhythmic, danceable new form of music through a mixture of soul music, jazz, and rhythm and blues (R&B). Funk de-emphasizes melody and chord progressions and focuses on a strong rhythmic groove of a bass line played by an electric bassist and a drum part played by a drummer. Like much of African-inspired music, funk typically consists of a complex groove with rhythm instruments playing interlocking grooves. Funk uses the same richly colored extended chords found in bebop jazz, such as minor chords with added sevenths and elevenths, or dominant seventh chords with altered ninths and thirteenths.

Funk originated in the mid-1960s, with James Brown's development of a signature groove that emphasized the downbeat—with heavy emphasis on the first beat of every measure ("The One"), and the application of swung 16th notes and syncopation on all bass lines, drum patterns, and guitar riffs.[2] Other musical groups, including Sly and the Family Stone, the Meters, and Parliament-Funkadelic, soon began to adopt and develop Brown's innovations. While much of the written history of funk focuses on men, there have been notable funk women, including Chaka Khan, Labelle, Lyn Collins, Brides of Funkenstein, Klymaxx, Mother's Finest, and Betty Davis.

Funk derivatives include the psychedelic funk of Sly Stone and George Clinton; the avant-funk of groups such as Talking Heads and the Pop Group; boogie, a form of post-disco dance music; electro music, a hybrid of electronic music and funk; funk metal (e.g., Living Colour, Faith No More); G-funk, a mix of gangsta rap and funk; Timba, a form of funky Cuban popular dance music; and funk jam (e.g., Phish). Funk samples and breakbeats have been used extensively in hip hop and various forms of electronic dance music, such as house music, old-school rave, breakbeat, and drum and bass. It is also the main influence of go-go, a subgenre associated with funk.[3]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 Characteristics

2.1 Rhythm

2.2 Harmony

3 History

3.1 New Orleans

3.2 1960s: James Brown

3.3 Late 1960s – early 1970s

3.4 P-Funk: Parliament-Funkadelic

3.5 1970s

3.6 Jazz funk

3.6.1 Headhunters

3.6.2 On the Corner

3.7 1980s and synthesizer funk

3.8 Late 1980s to present

3.9 Women and funk

4 Derivatives

4.1 Psychedelic funk

4.2 Funk rock

4.3 Avant-funk

4.4 Go-go

4.5 Boogie

4.6 Electro funk

4.7 Funk metal

4.8 G-funk

4.9 Timba funk

4.10 Funk jam

5 See also

6 Notes

7 References

Etymology

| Look up funk in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The word funk initially referred (and still refers) to a strong odor. It is originally derived from Latin "fumigare" (which means "to smoke") via Old French "fungiere" and, in this sense, it was first documented in English in 1620. In 1784 "funky" meaning "musty" was first documented, which, in turn, led to a sense of "earthy" that was taken up around 1900 in early jazz slang for something "deeply or strongly felt".[4][5][6]

In early jam sessions, musicians would encourage one another to "get down" by telling one another, "Now, put some stank on it!". At least as early as 1907, jazz songs carried titles such as Funky. The first example is an unrecorded number by Buddy Bolden, remembered as either "Funky Butt" or "Buddy Bolden's Blues" with improvised lyrics that were, according to Donald M. Marquis, either "comical and light" or "crude and downright obscene" but, in one way or another, referring to the sweaty atmosphere at dances where Bolden's band played.[7][8] As late as the 1950s and early 1960s, when "funk" and "funky" were used increasingly in the context of jazz music, the terms still were considered indelicate and inappropriate for use in polite company. According to one source, New Orleans-born drummer Earl Palmer "was the first to use the word 'funky' to explain to other musicians that their music should be made more syncopated and danceable."[9] The style later evolved into a rather hard-driving, insistent rhythm, implying a more carnal quality. This early form of the music set the pattern for later musicians.[10] The music was identified as slow, sexy, loose, riff-oriented and danceable.[citation needed]

Characteristics

Rhythm

The rhythm section of a funk band—the electric bass, drums, electric guitar and keyboards--are the heartbeat of the funk sound. Pictured here is the Meters.

A great deal of funk is rhythmically based on a two-celled onbeat/offbeat structure, which originated in sub-Saharan African music traditions. New Orleans appropriated the bifurcated structure from the Afro-Cuban mambo and conga in the late 1940s, and made it its own.[11] New Orleans funk, as it was called, gained international acclaim largely because James Brown's rhythm section used it to great effect.[12]

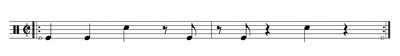

Simple kick and snare funk motif. The kick first sounds two onbeats, which are then answered by two offbeats. The snare sounds the backbeat.

Funk creates an intense groove by using strong guitar riffs and bass lines. Like Motown recordings, funk songs used bass lines as the centerpiece of songs. Slap bass's mixture of thumb-slapped low notes and finger "popped" (or plucked) high notes allowed the bass to have a drum-like rhythmic role, which became a distinctive element of funk.

In funk bands, guitarists typically play in a percussive style, using a style of picking called the "chank" or "chicken scratch", in which the guitar strings are pressed lightly against the fingerboard and then quickly released just enough to get a muted “scratching” sound that is produced by rapid rhythmic strumming of the opposite hand near the bridge.[13] The result of these factors was a rhythm guitar sound that seemed to float somewhere between the low-end thump of the electric bass and the cutting tone of the snare and hi-hats, with a rhythmically melodic feel that fell deep in the pocket. Guitarist Jimmy Nolen developed this technique. On James Brown's "Give It Up or Turnit a Loose" (1969), however, Jimmy Nolen's guitar part has a bare bones tonal structure. The pattern of attack-points is the emphasis, not the pattern of pitches. The guitar is used the way that an African drum, or idiophone would be used. Note that the measures alternate between beginning on the beat, and beginning on offbeats. Also often used was the application of the wah-wah sound effect and muting the notes in guitar riffs to create a percussive sound. Guitarist Ernie Isley of the Isley Brothers and Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic were notably influenced by Jimi Hendrix's improvised solos. Eddie Hazel, who worked with George Clinton, is one of the most notable guitar soloists in funk. Ernie Isley was tutored at an early age by Jimi Hendrix himself, when he was a part of the Isley Brothers backing band and temporarily lived in the attic at the Isleys' household.

Harmony

A thirteenth chord (E 13, which also contains a flat 7th and a 9th).

Funk uses the same richly coloured extended chords found in bebop jazz, such as minor chords with added sevenths and elevenths, or dominant seventh chords with altered ninths. However, unlike bebop jazz, with its complex, rapid-fire chord changes, funk virtually abandoned chord changes, creating static single chord vamps with melodo-harmonic movement and a complex, driving rhythmic feel. Some of the best known and most skilful soloists in funk have jazz backgrounds. Trombonist Fred Wesley and saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis and Maceo Parker are among the most notable musicians in the funk music genre, with both of them working with James Brown, George Clinton and Prince.

The chords used in funk songs typically imply a dorian or mixolydian mode, as opposed to the major or natural minor tonalities of most popular music. Melodic content was derived by mixing these modes with the blues scale. In the 1970s, jazz music drew upon funk to create a new subgenre of jazz-funk, which can be heard in recordings by Miles Davis (Live-Evil, On the Corner), and Herbie Hancock (Head Hunters).

History

The distinctive characteristics of African-American musical expression are rooted in sub-Saharan African music traditions, and find their earliest expression in spirituals, work chants/songs, praise shouts, gospel, blues, and "body rhythms" (hambone, patting juba, and ring shout clapping and stomping patterns). Funk music is an amalgam of soul music, soul jazz, R&B, and Afro-Cuban rhythms absorbed and reconstituted in New Orleans. Like other styles of African-American musical expression including jazz, soul music and R&B, funk music accompanied many protest movements during and after the Civil Rights Movement. Funk allowed everyday experiences to be expressed to challenge daily struggles and hardships fought by lower and working class communities.

New Orleans

Gerhard Kubik notes that with the exception of New Orleans, early blues lacked complex polyrhythms, and there was a "very specific absence of asymmetric time-line patterns (key patterns) in virtually all early twentieth century African-American music ... only in some New Orleans genres does a hint of simple time line patterns occasionally appear in the form of transient so-called 'stomp' patterns or stop-time chorus. These do not function in the same way as African time lines."[14]

In the late 1940s this changed somewhat when the two-celled time line structure was brought into New Orleans blues. New Orleans musicians were especially receptive to Afro-Cuban influences precisely at the time when R&B was first forming.[15]Dave Bartholomew and Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd) incorporated Afro-Cuban instruments, as well as the clave pattern and related two-celled figures in songs such as "Carnival Day" (Bartholomew 1949) and "Mardi Gras In New Orleans" (Longhair 1949). Robert Palmer reports that, in the 1940s, Professor Longhair listened to and played with musicians from the islands and "fell under the spell of Perez Prado's mambo records."[11] Professor Longhair's particular style was known locally as rumba-boogie.[16]

One of Longhair's great contributions was his particular approach of adopting two-celled, clave-based patterns into New Orleans rhythm and blues (R&B). Longhair's rhythmic approach became a basic template of funk. According to Dr. John (Malcolm John "Mac" Rebennack, Jr.), the Professor "put funk into music ... Longhair's thing had a direct bearing I'd say on a large portion of the funk music that evolved in New Orleans."[17] In his "Mardi Gras in New Orleans", the pianist employs the 2-3 clave onbeat/offbeat motif in a rumba-boogie "guajeo".[18]

The syncopated, but straight subdivision feel of Cuban music (as opposed to swung subdivisions) took root in New Orleans R&B during this time. Stewart states: "Eventually, musicians from outside of New Orleans began to learn some of the rhythmic practices [of the Crescent City]. Most important of these were James Brown and the drummers and arrangers he employed. Brown's early repertoire had used mostly shuffle rhythms, and some of his most successful songs were 12/8 ballads (e.g. 'Please, Please, Please' (1956), 'Bewildered' (1961), 'I Don't Mind' (1961)). Brown's change to a funkier brand of soul required 4/4 metre and a different style of drumming."[19] Stewart makes the point: "The singular style of rhythm & blues that emerged from New Orleans in the years after World War II played an important role in the development of funk. In a related development, the underlying rhythms of American popular music underwent a basic, yet generally unacknowledged transition from triplet or shuffle feel to even or straight eighth notes."[20]

1960s: James Brown

James Brown, a progenitor of funk music

Little Richard's saxophone-studded, mid-1950s R&B road band was credited by James Brown and others as being the first to put the funk in the rock'n'roll beat.[21] Following his temporary exit from secular music to become an evangelist in 1957, some of Little Richard's band members joined Brown and the Famous Flames, beginning a long string of hits for them in 1958. By the mid-1960s, James Brown had developed his signature groove that emphasized the downbeat—with heavy emphasis on the first beat of every measure to etch his distinctive sound, rather than the backbeat that typified African-American music.[22] Brown often cued his band with the command "On the one!," changing the percussion emphasis/accent from the one-two-three-four backbeat of traditional soul music to the one-two-three-four downbeat – but with an even-note syncopated guitar rhythm (on quarter notes two and four) featuring a hard-driving, repetitive brassy swing. This one-three beat launched the shift in Brown's signature music style, starting with his 1964 hit single, "Out of Sight" and his 1965 hits, "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag" and "I Got You (I Feel Good)".

Brown's style of funk was based on interlocking, contrapuntal parts: funky bass lines, drum patterns, and syncopated guitar riffs.[2] The main guitar ostinatos for "Ain't it Funky" (c. late 1960s) is an example of Brown's refinement of New Orleans funk— an irresistibly danceable riff, stripped down to its rhythmic essence. On "Ain't it Funky" the tonal structure is barebones. Brown's innovations led to him and his band becoming the seminal funk act; they also pushed the funk music style further to the forefront with releases such as "Cold Sweat" (1967), "Mother Popcorn" (1969) and "Get Up (I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine" (1970), discarding even the twelve-bar blues featured in his earlier music. Instead, Brown's music was overlaid with "catchy, anthemic vocals" based on "extensive vamps" in which he also used his voice as "a percussive instrument with frequent rhythmic grunts and with rhythm-section patterns ... [resembling] West African polyrhythms" – a tradition evident in African-American work songs and chants.[23] Throughout his career, Brown's frenzied vocals, frequently punctuated with screams and grunts, channeled the "ecstatic ambiance of the black church" in a secular context.[23]

After 1965, Brown's bandleader and arranger was Alfred "Pee Wee" Ellis. Ellis credits Clyde Stubblefield's adoption of New Orleans drumming techniques, as the basis of modern funk: "If, in a studio, you said 'play it funky' that could imply almost anything. But 'give me a New Orleans beat' – you got exactly what you wanted. And Clyde Stubblefield was just the epitome of this funky drumming."[24] Stewart states that the popular feel was passed along from "New Orleans—through James Brown's music, to the popular music of the 1970s."[20] Concerning the various funk motifs, Stewart states: "This model, it should be noted, is different from a time line (such as clave and tresillo) in that it is not an exact pattern, but more of a loose organizing principle."[25]

In a 1990 interview, Brown offered his reason for switching the rhythm of his music: "I changed from the upbeat to the downbeat ... Simple as that, really."[26] According to Maceo Parker, Brown's former saxophonist, playing on the downbeat was at first hard for him and took some getting used to. Reflecting back to his early days with Brown's band, Parker reported that he had difficulty playing "on the one" during solo performances, since he was used to hearing and playing with the accent on the second beat.[27]

Late 1960s – early 1970s

Other musical groups picked up on the rhythms and vocal style developed by James Brown and his band, and the funk style began to grow. Dyke and the Blazers, based in Phoenix, Arizona, released "Funky Broadway" in 1967, perhaps the first record of the soul music era to have "funky" in the title. In 1969 Jimmy McGriff released Electric Funk, featuring his distinctive organ over a blazing horn section. Meanwhile, on the West Coast, Charles Wright & the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band was releasing funk tracks beginning with its first album in 1967, culminating in the classic single "Express Yourself" in 1971. Also from the West Coast area, more specifically Oakland, San Francisco, came the band Tower of Power (TOP), which formed in 1968. Their debut album East Bay Grease, released 1970, is considered an important milestone in funk. Throughout the 1970s, TOP had many hits, and the band helped to make funk music a successful genre, with a broader audience.

In 1970, Sly & the Family Stone's "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" reached #1 on the charts, as did "Family Affair" in 1971. Notably, these afforded the group and the genre crossover success and greater recognition, yet such success escaped comparatively talented and moderately popular funk band peers. The Meters defined funk in New Orleans, starting with their top ten R&B hits "Sophisticated Cissy" and "Cissy Strut" in 1969. Another group who defined funk around this time were the Isley Brothers, whose funky 1969 #1 R&B hit, "It's Your Thing", signaled a breakthrough in African-American music, bridging the gaps of the jazzy sounds of Brown, the psychedelic rock of Jimi Hendrix, and the upbeat soul of Sly & the Family Stone and Mother's Finest. The Temptations, who had previously helped to define the "Motown Sound" – a distinct blend of pop-soul – adopted this new psychedelic sound towards the end of the 1960s as well. Their producer, Norman Whitfield, became an innovator in the field of psychedelic soul, creating hits with a newer, funkier sound for many Motown acts, including "War" by Edwin Starr, "Smiling Faces Sometimes" by the Undisputed Truth and "Papa Was A Rollin' Stone" by the Temptations. Motown producers Frank Wilson ("Keep On Truckin'") and Hal Davis ("Dancing Machine") followed suit. Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye also adopted funk beats for some of their biggest hits in the 1970s, such as "Superstition" and "You Haven't Done Nothin'", and "I Want You" and "Got To Give It Up", respectively.

P-Funk: Parliament-Funkadelic

George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic in 2006

A new group of musicians began to further develop the "funk rock" approach. Innovations were prominently made by George Clinton, with his bands Parliament and Funkadelic. Together, they produced a new kind of funk sound heavily influenced by jazz and psychedelic rock. The two groups shared members and are often referred to collectively as "Parliament-Funkadelic." The breakout popularity of Parliament-Funkadelic gave rise to the term "P-Funk", which referred to the music by George Clinton's bands, and defined a new subgenre. Clinton played a principal role in several other bands, including Parlet, the Horny Horns, and the Brides of Funkenstein, all part of the P-Funk conglomerate. "P-funk" also came to mean something in its quintessence, of superior quality, or sui generis.

1970s

The Original Family Stone live, 2006. Jerry Martini, Rose Stone, and Cynthia Robinson

The 1970s were the era of highest mainstream visibility for funk music. In addition to Parliament Funkadelic, artists like Sly and the Family Stone, Rufus & Chaka Khan, Bootsy's Rubber Band, the Isley Brothers, Ohio Players, Con Funk Shun, Kool and the Gang, the Bar-Kays, Commodores, Roy Ayers, Stevie Wonder, among others, were successful in getting radio play. Disco music owed a great deal to funk. Many early disco songs and performers came directly from funk-oriented backgrounds. Some disco music hits, such as all of Barry White's hits, "Kung Fu Fighting" by Biddu and Carl Douglas, Donna Summer's "Love To Love You Baby", Diana Ross' "Love Hangover", KC and the Sunshine Band's "I'm Your Boogie Man", "I'm Every Woman" by Chaka Khan (also known as the Queen of Funk), and Chic's "Le Freak" conspicuously include riffs and rhythms derived from funk. In 1976, Rose Royce scored a number-one hit with a purely dance-funk record, "Car Wash". Even with the arrival of Disco, funk became increasingly popular well into the early '80s.

Funk music was also exported to Africa, and it melded with African singing and rhythms to form Afrobeat. Nigerian musician Fela Kuti, who was heavily influenced by James Brown's music, is credited with creating the style and terming it "Afrobeat".

Jazz funk

Headhunters

In the 1970s, at the same time that jazz musicians began to explore blending jazz with rock to create jazz fusion, major jazz performers began to experiment with funk. Jazz-funk recordings typically used electric bass and electric piano in the rhythm section, in place of the double bass and acoustic piano that were typically used in jazz up till that point. Pianist and bandleader Herbie Hancock was the first of many big jazz artists who embraced funk during the decade. Hancock's Headhunters band (1973) played the jazz-funk style. The Headhunters' lineup and instrumentation, retaining only wind player Bennie Maupin from Hancock's previous sextet, reflected his new musical direction. He used percussionist Bill Summers in addition to a drummer. Summers blended African, Afro-Cuban, and Afro-Brazilian instruments and rhythms into Hancock's jazzy funk sound.

On the Corner

On the Corner (1972) was jazz trumpeter-composer Miles Davis's seminal foray into jazz-funk. Like his previous works though, On the Corner was experimental. Davis stated that On the Corner was an attempt at reconnecting with the young black audience which had largely forsaken jazz for rock and funk. While there is a discernible funk influence in the timbres of the instruments employed, other tonal and rhythmic textures, such as the Indian tambora and tablas, and Cuban congas and bongos, create a multi-layered soundscape. From a musical standpoint, the album was a culmination of sorts of the recording studio-based musique concrète approach that Davis and producer Teo Macero (who had studied with Otto Luening at Columbia University's Computer Music Center) had begun to explore in the late 1960s. Both sides of the record featured heavy funk drum and bass grooves, with the melodic parts snipped from hours of jams and mixed in the studio.

Also cited as musical influences on the album by Davis were the contemporary composer Karlheinz Stockhausen.[28][29]

1980s and synthesizer funk

In the 1980s, largely as a reaction against what was seen as the over-indulgence of disco, many of the core elements that formed the foundation of the P-Funk formula began to be usurped by electronic instruments, drum machines and synthesizers. Horn sections of saxophones and trumpets were replaced by synth keyboards, and the horns that remained were given simplified lines, and few horn solos were given to soloists. The classic electric keyboards of funk, like the Hammond B3 organ, the Hohner Clavinet and/or the Fender Rhodes piano began to be replaced by the new digital synthesizers such as the Yamaha DX7. Electronic drum machines such as the Roland TR-808 began to replace the "funky drummers" of the past, and the slap and pop style of bass playing were often replaced by synth keyboard bass lines. Lyrics of funk songs began to change from suggestive double entendres to more graphic and sexually explicit content.

In the late 1970s, the electronic music band Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) began experimenting with electronic funk music, introducing "videogame-funk" sounds with hits such as "Computer Game" (1978), which had a strong influence on the later electro-funk genre.[30] In 1980, YMO was the first band to use the TR-808 programmable drum machine,[31] while YMO member Ryuichi Sakamoto's "Riot in Lagos" developed the beats and sounds of electro-funk that same year,[32] influencing later electro-funk artists such as Afrika Bambaataa[32] and Mantronix.[33]

Rick James was the first funk musician of the 1980s to assume the funk mantle dominated by P-Funk in the 1970s. His 1981 album Street Songs, with the singles "Give It to Me Baby" and "Super Freak", resulted in James becoming a star, and paved the way for the future direction of explicitness in funk.

Prince was an influential multi-instrumentalist, bandleader, singer and songwriter.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Prince used a stripped-down, dynamic instrumentation similar to James. However, Prince went on to have as much of an impact on the sound of funk as any one artist since Brown; he combined eroticism, technology, an increasing musical complexity, and an outrageous image and stage show to ultimately create music as ambitious and imaginative as P-Funk. Prince formed the Time, originally conceived as an opening act for him and based on his "Minneapolis sound", hybrid mixture of funk, R&B, rock, pop & new wave. Eventually, the band went on to define their own style of stripped-down funk based on tight musicianship and sexual themes.

Similar to Prince, other bands emerged during the P-Funk era and began to incorporate uninhibited sexuality, dance-oriented themes, synthesizers and other electronic technologies to continue to craft funk hits. These included Cameo, Zapp, the Gap Band, the Bar-Kays, and the Dazz Band all found their biggest hits in the early 1980s. By the latter half of the 80s, pure funk had lost its commercial impact; however, pop artists from Michael Jackson to Duran Duran often used funk beats.

Influenced by Yellow Magic Orchestra[32] and Kraftwerk, the American musician Afrika Bambaataa developed electro-funk, a minimalist machine-driven style of funk with his single "Planet Rock" in 1982. Also known simply as electro, this style of funk was driven by synthesizers and the electronic rhythm of the TR-808 drum machine. The single "Renegades of Funk" followed in 1983.

Late 1980s to present

While funk was all but driven from the radio by slick commercial hip hop, contemporary R&B and new jack swing, its influence continued to spread. Artists like Steve Arrington and Cameo still received major airplay and had huge global followings. Rock bands began copying elements of funk to their sound, creating new combinations of "funk rock" and "funk metal". Extreme, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Living Colour, Jane's Addiction, Prince, Primus, Fishbone, Faith No More, Rage Against the Machine, Infectious Grooves, and Incubus spread the approach and styles garnered from funk pioneers to new audiences in the mid-to-late 1980s and the 1990s. These bands later inspired the underground mid-1990s funkcore movement and current funk-inspired artists like Outkast, Malina Moye, Van Hunt, and Gnarls Barkley.

In the 1990s, artists like Me'shell Ndegeocello and the (predominantly UK-based) acid jazz movement including artists and bands such as Jamiroquai, Incognito, Galliano, Omar, Los Tetas and the Brand New Heavies carried on with strong elements of funk. However, they never came close to reaching the commercial success of funk in its heyday, with the exception of Jamiroquai whose album Travelling Without Moving sold about 11.5 million units worldwide. Meanwhile, in Australia and New Zealand, bands playing the pub circuit, such as Supergroove, Skunkhour and the Truth, preserved a more instrumental form of funk.

Since the late 1980s hip hop artists have regularly sampled old funk tunes. James Brown is said to be the most sampled artist in the history of hip hop, while P-Funk is the second most sampled artist; samples of old Parliament and Funkadelic songs formed the basis of West Coast G-funk.

Original beats that feature funk-styled bass or rhythm guitar riffs are also not uncommon. Dr. Dre (considered the progenitor of the G-funk genre) has freely acknowledged to being heavily influenced by George Clinton's psychedelic funk: "Back in the 70s that's all people were doing: getting high, wearing Afros, bell-bottoms and listening to Parliament-Funkadelic. That's why I called my album The Chronic and based my music and the concepts like I did: because his shit was a big influence on my music. Very big".[34]Digital Underground was a large contributor to the rebirth of funk in the 1990s by educating their listeners with knowledge about the history of funk and its artists. George Clinton branded Digital Underground as "Sons of the P", as their second full-length release is also titled. DU's first release, Sex Packets, was full of funk samples, with the most widely known "The Humpty Dance" sampling Parliament's "Let's Play House". A very strong funk album of DU's was their 1996 release Future Rhythm. Much of contemporary club dance music, drum and bass in particular has heavily sampled funk drum breaks.

Funk is a major element of certain artists identified with the jam band scene of the late 1990s and 2000s. Phish began playing funkier jams in their sets around 1996, and 1998's The Story of the Ghost was heavily influenced by funk. Medeski Martin & Wood, Robert Randolph & the Family Band, Galactic, Widespread Panic, Jam Underground, Diazpora, Soulive, and Karl Denson's Tiny Universe all drawing heavily from the funk tradition. Lettuce, a band of Berklee College Of Music graduates, was formed in the late 1990s as a pure-funk emergence was being felt through the jam band scene.[citation needed] Many members of the band including keyboardist Neal Evans went on to other projects such as Soulive or the Sam Kininger Band. Dumpstaphunk builds upon the New Orleans tradition of funk, with their gritty, low-ended grooves and soulful four-part vocals. Formed in 2003 to perform at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, the band features keyboardist Ivan Neville and guitarist Ian Neville of the famous Neville family, with two bass players and female funk drummer Nikki Glaspie (formerly of Beyoncé Knowles's world touring band, as well as the Sam Kininger Band), who joined the group in 2011.

Since the mid-1990s the nu-funk scene, centered on the Deep Funk collectors scene, is producing new material influenced by the sounds of rare funk 45s. Labels include Desco, Soul Fire, Daptone, Timmion, Neapolitan, Bananarama, Kay-Dee, and Tramp. These labels often release on 45 rpm records. Although specializing in music for rare funk DJs, there has been some crossover into the mainstream music industry, such as Sharon Jones' 2005 appearance on Late Night with Conan O'Brien.

In the early 2000s, some punk funk bands such as Out Hud and Mongolian MonkFish perform in the indie rock scene. Indie band Rilo Kiley, in keeping with their tendency to explore a variety of rockish styles, incorporated funk into their song "The Moneymaker" on the album Under the Blacklight. Prince, with his later albums, gave a rebirth to the funk sound with songs like "The Everlasting Now", "Musicology", "Ol' Skool Company", and "Black Sweat".

Funk has also been incorporated into modern R&B music by many female singers such as Beyoncé with her 2003 hit "Crazy in Love" (which samples the Chi-Lites' "Are You My Woman"), Mariah Carey in 2005 with "Get Your Number" (which samples "Just an Illusion" by British band Imagination), Jennifer Lopez in 2005 with "Get Right" (which samples Maceo Parker's "Soul Power '74" horn sound), and also Amerie with her song "1 Thing" (which samples the Meters' "Oh, Calcutta!"). Tamar Braxton in 2013 with "The One" (which samples "Juicy Fruit" by Mtume).

Chaka Khan (born 1953) has been called the "Queen of Funk."

Women and funk

Despite funk's popularity in modern music, few people have examined the work of funk women. Notable funk women include Chaka Khan, Labelle, Brides of Funkenstein, Klymaxx, Mother's Finest, Lyn Collins, Betty Davis and Teena Marie. As cultural critic Cheryl Keyes explains in her essay "She Was Too Black for Rock and Too Hard for Soul: (Re)discovering the Musical Career of Betty Mabry Davis," most of the scholarship around funk has focused on the cultural work of men. She states that "Betty Davis is an artist whose name has gone unheralded as a pioneer in the annals of funk and rock. Most writing on these musical genres has traditionally placed male artist like Jimi Hendrix, George Clinton (of Parliament-Funkadelic), and bassist Larry Graham as trendsetters in the shaping of a rock music sensibility".[35]

In The Feminist Funk Power of Betty Davis and Renée Stout, Nikki A. Greene,[36] notes that Davis' provocative and controversial style helped her rise to popularity in the 1970s as she focused on sexually motivated, self-empowered subject matter. Furthermore, this affected the young artist's ability to draw large audiences and commercial success. Greene also notes that Davis was never made an official spokesperson or champion for the civil rights and feminist movements of the time, although more recently[when?] her work has become a symbol of sexual liberation for women of color. Davis' song "If I'm In Luck I Just Might Get Pick Up", on her self-titled debut album, sparked controversy and was banned by the Detroit NAACP.[dubious ] Maureen Mahan, a musicologist and anthropologist, examines Davis' impact on the music industry and the American public in her article "They Say She's Different: Race Gender, Genre and the Liberated Black Femininity of Betty Davis." Mahan notes that Davis "took pleasure in her frank and public exploration of a black woman's sexual agency, but she did so in a context that offered limited opportunities for black female-centered expressions" (24).[citation needed]

Laina Dawes, the author of What Are You Doing Here: A Black Woman's Life and Liberation in Heavy Metal, believes respectability politics is the reason artists like Davis do not get the same recognition as their male counterparts: "I blame what I call respectability politics as part of the reason the funk-rock some of the women from the '70s aren't better known.[verify] Despite the importance of their music and presence, many of the funk-rock females represented the aggressive behavior and sexuality that many people were not comfortable with."[citation needed]

According to Francesca T. Royster, in Rickey Vincent's book Funk: The Music, The People, and The Rhythm of The One, he analyzes the impact of Labelle but only in limited sections. Royster criticizes Vincent's analysis of the group, stating: "It is a shame, then, that Vincent gives such minimal attention to Labelle's performances in his study. This reflects, unfortunately, a still consistent sexism that shapes the evaluation of funk music. In Funk, Vincent's analysis of Labelle is brief—sharing a single paragraph with the Pointer Sisters in his three-page sub chapter, 'Funky Women.' He writes that while 'Lady Marmalade' 'blew the lid off of the standards of sexual innuendo and skyrocketed the group's star status,' the band's 'glittery image slipped into the disco undertow and was ultimately wasted as the trio broke up in search of solo status' (Vincent, 1996, 192).'[37] Many female artists who are considered to be in the genre of funk, also share songs in the disco, soul, and R&B genres; Labelle falls into this category of women who are split among genres due to critical view of music theory and the history of sexism in the United States.[38]

In recent years,[when?] artists like Janelle Monáe have opened the doors for more scholarship and analysis on the female impact on the funk music genre.[dubious ] Monáe's style bends concepts of gender, sexuality, and self-expression in a manner similar to the way some male pioneers in funk broke boundaries.[39] Her albums center around Afro-futuristic concepts, centering on elements of female and black empowerment and visions of a dystopian future.[40] In his article, "Janelle Monáe and Afro-sonic Feminist Funk", Matthew Valnes writes that Monae's involvement in the funk genre is juxtaposed with the traditional view of funk as a male-centered genre. Valnes acknowledges that funk is male-dominated, but provides insight to the societal circumstances that led to this situation.[39][clarification needed]

Monáe's influences include her mentor Prince, Funkadelic, Lauryn Hill, and other funk and R&B artists, but according to Emily Lordi, "[Betty] Davis is seldom listed among Janelle Monáe's many influences, and certainly the younger singer's high-tech concepts, virtuosic performances, and meticulously produced songs are far removed from Davis's proto-punk aesthetic. But... like Davis, she also is closely linked with a visionary male mentor (Prince). The title of Monáe's 2013 album, The Electric Lady, alludes to Hendrix's Electric Ladyland, but it also implicitly cites the coterie of women that inspired Hendrix himself: that group, called the Cosmic Ladies or Electric Ladies, was together led by Hendrix's lover Devon Wilson and Betty Davis."[41]

Derivatives

From the early 1970s onwards, funk has developed various subgenres. While George Clinton and the Parliament were making a harder variation of funk, bands such as Kool and the Gang, Ohio Players and Earth, Wind and Fire were making disco-influenced funk music.[42]

Psychedelic funk

Following the work of Jimi Hendrix in the late 1960s, black funk artists such as Sly and the Family Stone pioneered a style known as psychedelic funk by borrowing techniques from psychedelic rock music, including wah pedals, fuzz boxes, echo chambers, and vocal distorters, as well as blues rock and jazz.[43] In the following years, groups such as George Clinton's Parliament-Funkadelic continued this sensibility, employing synthesizers and rock-oriented guitar work.[43]

Funk rock

Funk rock (also written as funk-rock or funk/rock) fuses funk and rock elements.[44] Its earliest incarnation was heard in the late '60s through the mid-'70s by musicians such as Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, Steely Dan, Herbie Hancock, Return to Forever, Gary Wright, David Bowie, Betty Davis, Mother's Finest, and Funkadelic on their earlier albums.

Many instruments may be incorporated into funk rock, but the overall sound is defined by a definitive bass or drum beat and electric guitars. The bass and drum rhythms are influenced by funk music but with more intensity, while the guitar can be funk-or-rock-influenced, usually with distortion. Prince, Jesse Johnson, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Fishbone are major artists in funk rock.

Avant-funk

The term "avant-funk" has been used to describe acts who combined funk with art rock's concerns.[45]Simon Frith described the style as an application of progressive rock mentality to rhythm rather than melody and harmony.[45]Simon Reynolds characterized avant-funk as a kind of psychedelia in which "oblivion was to be attained not through rising above the body, rather through immersion in the physical, self loss through animalism."[45]

Talking Heads combined funk with elements of post-punk and art rock.

Acts in the genre include German krautrock band Can,[46] American funk artists Sly Stone and George Clinton,[47] and a wave of early 1980s UK and US post-punk artists (including Public Image Ltd, Talking Heads, the Pop Group, Cabaret Voltaire, D.A.F., A Certain Ratio, and 23 Skidoo)[48] who embraced black dance music styles such as disco and funk.[49] The artists of the late 1970s New York no wave scene also explored avant-funk, influenced by figures such as Ornette Coleman.[50] Reynolds noted these artists' preoccupations with issues such as alienation, repression and technocracy of Western modernity.[45]

Go-go

Go-go originated in the Washington, D.C. area with which it remains associated, along with other spots in the Mid-Atlantic. Inspired by singers such as Chuck Brown, the "Godfather of Go-go", it is a blend of funk, rhythm and blues, and early hip hop, with a focus on lo-fi percussion instruments and in-person jamming in place of dance tracks. As such, it is primarily a dance music with an emphasis on live audience call and response. Go-go rhythms are also incorporated into street percussion.

Boogie

Boogie (or electro-funk) is an electronic music mainly influenced by funk and post-disco. The minimalist approach of boogie, consisting of synthesizers and keyboards, helped to establish electro and house music. Boogie, unlike electro, emphasises the slapping techniques of bass guitar but also bass synthesizers. Artists include Vicky "D", Komiko, Peech Boys, Kashif, and later Evelyn King.

Electro funk

Electro funk is a hybrid of electronic music and funk. It essentially follows the same form as funk, and retains funk's characteristics, but is made entirely (or partially) with a use of electronic instruments such as the TR-808. Vocoders or talkboxes were commonly implemented to transform the vocals. The pioneering Electro band Zapp commonly used such instruments in their music. Other artists include Herbie Hancock, Afrika Bambaataa, Egyptian Lover, Vaughan Mason & Crew, Midnight Star and Cybotron.

Funk metal

Funk metal (sometimes typeset differently such as funk-metal) is a fusion genre of music which emerged in the 1980s, as part of the alternative metal movement. It typically incorporates elements of funk and heavy metal (often thrash metal), and in some cases other styles, such as punk and experimental music. It features hard-driving heavy metal guitar riffs, the pounding bass rhythms characteristic of funk, and sometimes hip hop-style rhymes into an alternative rock approach to songwriting. A primary example is the all-African-American rock band Living Colour, who have been said to be "funk-metal pioneers" by Rolling Stone.[51] During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the style was most prevalent in California – particularly Los Angeles and San Francisco.[52][53]

G-funk

G-funk is a fusion genre of music which combines gangsta rap and funk. It is generally considered to have been invented by west coast rappers and made famous by Dr. Dre. It incorporates multi-layered and melodic synthesizers, slow hypnotic grooves, a deep bass, background female vocals, the extensive sampling of P-Funk tunes, and a high-pitched portamento saw wave synthesizer lead. Unlike other earlier rap acts that also utilized funk samples (such as EPMD and the Bomb Squad), G-funk often used fewer, unaltered samples per song.

Timba funk

Timba is a form of funky Cuban popular dance music. By 1990, several Cuban bands had incorporated elements of funk and hip-hop into their arrangements, and expanded upon the instrumentation of the traditional conjunto with American drum set, saxophones and a two-keyboard format. Timba bands like La Charanga Habanera or Bamboleo often have horns or other instruments playing short parts of tunes by Earth, Wind and Fire, Kool and the Gang or other U.S. funk bands. While many funk motifs exhibit a clave-based structure, they are created intuitively, without a conscious intent of aligning the various parts to a guide-pattern. Timba incorporates funk motifs into an overt and intentional clave structure.

Funk jam

Funk jam is a fusion genre of music which emerged in the 1990s. It typically incorporates elements of funk and often exploratory guitar, along with extended cross genre improvisations; often including elements of jazz, ambient, electronic, Americana, and hip hop including improvised lyrics. Phish, Soul Rebels Brass Band, Galactic, Soulive are all examples of funk bands that play funk jam.

See also

- Chanking

- List of funk musicians

Notes

^ Presence and pleasure: the funk grooves of James Brown and Parliament, p.3

^ ab Slutsky, Allan, Chuck Silverman (1997). The Funkmasters-the Great James Brown Rhythm Sections. .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 1-57623-443-6

^ Vincent, Rickey (1996). Funk: The Music, the People, and the Rhythm of the One. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 293–297. ISBN 978-0-312-13499-0.

^ "Online Etymology Dictionary – Funk". Etymonline.com. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

^ "Online Etymology Dictionary – funky". Etymonline.com. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

^ Quinion, Michael (October 27, 2001). "World Wide Words: Funk". World Wide Words. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

^ Donald M. Marquis: In Search of Buddy Bolden, Louisiana State University Press, 2005, p. 108-111

ISBN 978-0-8071-3093-3

^ Who Started Funk Music Archived October 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Real Music Forum

^ Obituary, The Guardian

^ Merriam-Webster, Inc, The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories (Merriam-Webster, 1991),

ISBN 0-87779-603-3, p. 175.

^ ab Palmer, Robert (1979: 14), A Tale of Two Cities: Memphis Rock and New Orleans Roll. Brooklyn.

^ Stewart, Alexander (2000: 293), "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music", Popular Music, v. 19, n. 3, October 2000), p. 293–318.

^ "The Funky Ones — What Makes Funk Guitar What It Is - Musical U". Musical-u.com. August 15, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

^ Kubik (1999: 51). Africa and the Blues. Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi.

^ "Rhythm and blues influenced by Afro-Cuban music first surfaced in New Orleans." Campbell, Michael, and James Brody (2007: 83). Rock and Roll: An Introduction. Schirmer.

ISBN 0-534-64295-0

^ Stewart, Alexander (2000: 298). "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music." Popular Music, v. 19, n. 3. Oct. 2000), p. 293–318.

^ Dr. John quoted by Stewart (2000: 297).

^ Kevin Moore: "There are two common ways that the three-side [of clave] is expressed in Cuban popular music. The first to come into regular use, which David Peñalosa calls 'clave motif,' is based on the decorated version of the three-side of the clave rhythm. By the 1940s [there was] a trend toward the use of what Peñalosa calls the 'offbeat/onbeat motif.' Today, the offbeat/onbeat motif method is much more common." Moore (2011). Understanding Clave and Clave Changes p. 32. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com.

ISBN 1466462302

^ Stewart (2000: 302).

^ ab Stewart (2000: 293).

^ "Little Richard". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

^ Lessons in listening – Concepts section: Fantasy, Earth Wind & Fire, The Best of Earth Wind & Fire Volume I, Freddie White. (January 1998). Modern Drummer Magazine, pp. 146–152. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

^ ab Collins, W. (January 29, 2002). James Brown. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

^ Alfred "Pee Wee" Ellis quoted by Stewart (2000: 303).

^ Stewart (2000: 306).

^ Pareles, J. (December 26, 2006). James Brown, the "Godfather of Soul" dies at 73. The New York Times. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

^ Gross, T. (1989). Musician Maceo Parker (Fresh Air WHYY-FM audio interview). National Public Radio. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

^ "Miles Davis first heard Stockhausen's music in 1972, and its impact can be felt in Davis's 1972 recording On the Corner, in which cross-cultural elements are mixed with found elements." Barry Bergstein "Miles Davis and Karlheinz Stockhausen: A Reciprocal Relationship." The Musical Quarterly 76, no. 4. (Winter): p. 503.

^ In Davis' autobiography he states that "I had always written in a circular way and through Stockhausen I could see that I didn't want to ever play again from eight bars to eight bars, because I never end songs: they just keep going on. Through Stockhausen I understood music as a process of elimination and addition" (Miles, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989, p. 329)

^ Dayal, Gheeta (July 7, 2006). "Yellow Magic Orchestra". Groove. The Original Soundtrack. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

^ Jason Anderson (November 28, 2008). "Slaves to the rhythm: Kanye West is the latest to pay tribute to a classic drum machine". CBC News. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

^ abc David Toop (March 1996), "A-Z Of Electro", The Wire (145), retrieved May 29, 2011

^ "Kurtis Mantronik Interview", Hip Hop Storage, July 2002, archived from the original on May 24, 2011, retrieved May 25, 2011

^ Dr. Dre > Biography at MyStrands Archived February 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

^ Cheryl Keyes (2013). "She Was too Black for Rock and too hard for Soul: (Re)discovering the Musical Career of Betty Mabry Davis". American Studies. 52: 35.

^ Nikki A. Greene (2013). "The Feminist Funk Power of Betty Davis and Renée Stout". American Studies. 52: 57–76. JSTOR 24589269.

^ Royster, Francesca T. (2013). "Labelle: Funk, Feminism, and the Politics of Flight and Fight". American Studies. 52 (4): 77–98. doi:10.1353/ams.2013.0120. ISSN 2153-6856.

^ "On the Difference Between Funk and Disco". The Washington Post. August 1, 1979. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

^ ab Valnes, Matthew (September 2017). "Janelle Monáe and Afro-Sonic Feminist Funk". Journal of Popular Music Studies. 29 (3): e12224. doi:10.1111/jpms.12224. ISSN 1524-2226.

^ "Janelle Monáe's body of work is a masterpiece of modern science fiction". Vox. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

^ Lordi, Emily (May 2, 2018). "The Artful, Erotic, and Still Misunderstood Funk of Betty Davis". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

^ Presence and pleasure: the funk grooves of James Brown and Parliament, p.4

^ ab Scott, Derek B. "Dayton Street Funk: The Layering of Musical Identities". The Ashgate Research Companion to Popular Musicology. p. 275. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

^ Vincent, Rickey (2004). "Hip-Hop and Black Noise:Raising Hell". That's the Joint!: The Hip-hop Studies Reader. pp. 489–490. ISBN 0-415-96919-0.

^ abcd Reynolds, Simon. "End of the Track". New Statesman. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

^ Reynolds, Simon (1995). "Krautrock Reissues". Melody Maker. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

^ "Passings". Billboard (116). Nielsen. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

^ Reynolds, Simon (2012). Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. Soft Skull Press. pp. 20, 202. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

^ Reynolds, Simon (2006). Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984. Penguin.

^ Murray, Charles Shaar (October 1991). Crosstown Traffic: Jimi Hendrix & The Post-War Rock 'N' Roll Revolution. Macmillan. p. 205. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

^ Fricke, David (November 13, 2003). "Living Colour – Collideoscope". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 12, 2009. Retrieved December 11, 2011.Black-funk-metal pioneers return in righteous form when black-rock warriors Living Colour broke up in 1995,

^ Potter, Valerie (July 1991). "Primus: Nice and Cheesy". Hot Metal. Sydney, Australia. 29.

^ Darzin, Daina; Spencer, Lauren (January 1991). "The Thrash-Funk scene proudly presents Primus". Spin. 6 (10): 39.

References

Vincent, Rickey (1996). Funk: The Music, The People, and The Rhythm of The One. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-13499-1.

Thompson, Dave (2001). Funk. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-629-7.

Wermelinger, Peter (2005). Funky & Groovy Music Records Lexicon. -. ISBN 3-9522773-1-2.