Mexican Army

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Mexican Army | |

|---|---|

| Ejército Mexicano | |

Mexican Army emblem | |

| Active | 19th(XIX) century – present |

| Country | Mexico |

| Type | Army and naval force |

| Size | 274,500 active personnel 110,500 reserve personnel (2018) |

| Part of | Secretariat of National Defense Mexican Armed Forces |

| Motto(s) | Siempre Leales (Always Loyal) |

| Mascot(s) | Golden eagle |

| Anniversaries | 19 February, Day of the Army.[1] 13 September, Día de los Niños Héroes.[2] |

| Equipment | See: Equipment |

| Engagements | War of Independence Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico Texas Revolution Pastry War Capture of Monterey Mexican–American War Caste War of Yucatán Reform War French Intervention Mexican Revolution Border War Cristero War World War II Dirty War Zapatista Uprising Mexican Drug War |

| Insignia | |

| Guidon |  |

| Flag (unofficial) |  |

The Mexican Army (Spanish: Ejército Mexicano) is the combined land and air branch and is the largest of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

It was the first army to adopt (1908) and use (1910) a self-loading rifle, the Mondragón rifle. The Mexican Army has an active duty force of 274,500 with 110,500 men and women of military service age (2015 est.).

Mexico has no major foreign nation-state adversaries. It officially repudiates the use of force to settle disputes and rejects interference by one nation in the affairs of another. Although it has not suffered a major international terrorist incident in recent decades, the Mexican government considers the country a potential target for international terrorism.[3]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Antecedents

1.1.1 Pre-Columbian era: native warriors

1.1.2 Military in the Spanish Colonial Era

1.2 Independence

1.3 Pastry War

1.4 U.S. invasion

1.5 French Intervention

1.5.1 Mexican Republican forces

1.6 Díaz era

1.7 Mexican Revolution 1910–1920

1.8 Contemporary era

1.8.1 Post-revolutionary period

1.8.2 Mexican Drug War

2 Military Organization in the Modern Era

2.1 Regional command

2.2 Tactical units

2.3 Special Forces Corps

2.3.1 Special Operations Forces

2.4 Estado Mayor Presidencial

2.5 Paratrooper Corps

3 Ranks

4 Military Industry

5 Modern equipment of the Mexican Army

5.1 Vehicles

5.2 Individual weapons

5.3 Artillery

5.4 Anti-armor weapons

6 Future

7 See also

8 Further reading

8.1 Colonial era

8.2 Post-Independence

9 References

10 External links

History

Antecedents

Pre-Columbian era: native warriors

Aztec warriors as shown in the 16th century Florentine Codex. Note that each warrior is brandishing a Maquahuitl.

This page from the Codex Mendoza shows the gradual improvements to equipment and tlahuiztli as a warrior progresses through the ranks from commoner to porter to warrior to captor, and later as a noble progressing in the warrior societies from the noble warrior to "Eagle warrior" to "Jaguar Warrior" to "Otomitl" to "Shorn One" and finally as "Tlacateccatl".

Tepoztōpīlli from the Armeria Real collection in Madrid

In the prehispanic era, there were many indigenous tribes and highly developed city-states in what is now known as central Mexico. The most advanced and powerful kingdoms were those of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan, which comprised populations of the same ethnic origin and were politically linked by an alliance known as the Triple Alliance; colloquially these three states are known as the Aztec. They had a center for higher education called the Calmecac in Nahuatl, this was where the children of the Aztec priesthood and nobility receive rigorous religious and military training and conveyed the highest knowledge such as: doctrines, divine songs, the science of interpreting codices, calendar skills, memorization of texts, etc. In Aztec society, it was compulsory for all young males, nobles as well as commoners, to join part of the armed forces at the age of 15. Recruited by regional and clan groups (calpulli) the conscripts were organized in units of about 8,000 men (Xiquipilli). These were broken down into 400 strong sub-units. Aztec nobility (some of whom were the children of commoners who had distinguished themselves in battle) led their own serfs on campaign.[4]

Itzcoatl "Obsidian Serpent" (1381–1440), fourth king of Tenochtitlán, organized the army that defeated the Tepanec of Atzcapotzalco, freeing his people from their dominion. His reign began with the rise of what would become the largest empire in Mesoamerica. Then Moctezuma Ilhuicamina "The arrow to the sky" (1440–1469) came to extend the domain and the influence of the monarchy of Tenochtitlán. He began to organize trade to the outside regions of the Valley of Mexico. This was the Mexica ruler who organized the alliance with the lordships of Texcoco and Tlacopan to form the Triple Alliance.

The Aztec established the Flower Wars as a form of worship; these, unlike the wars of conquest, were aimed at obtaining prisoners for sacrifice to the sun. Combat orders were given by kings (or Lords) using drums or blowing into a sea snail shell that gave off a sound like a horn. Giving out signals using coats of arms was very common. For combat outside of cities, they would organize several groups, only one of which would be involved in action, while the others remained on the alert. When attacking enemy cities, they usually divided their forces into three equal-sized wings, which simultaneously assaulted different parts of the defences – this enabled the leaders to determine which division of warriors had distinguished themselves the most in combat.[5]

Military in the Spanish Colonial Era

During the 18th century the Spanish colonial forces in the greater Mexico region consisted of regular "Peninsular" regiments sent from Spain itself, augmented by locally recruited provincial and urban militia units of infantry, cavalry and artillery. A few regular infantry and dragoon regiments (e.g. the Regimiento de Mexico) were recruited within Mexico and permanently stationed there.[6] Mounted units of soldados de cuera (so called from the leather protective clothing that they wore)[7]

patrolled frontier and desert regions.[8]

Independence

In the early morning of 16 September 1810, the Army of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla initiated the independence movement. Hidalgo was followed by his loyal companions, among them Mariano Abasolo, and a small army equipped with swords, spears, slingshots and sticks. Captain General Ignacio Allende was the military brains of the insurgent army in the first phase of the War of Independence and secured several victories over the Spanish Royal Army. Their troops were about 5,000 strong and were later joined by squadrons of the Queen's Regiment where its members in turn contributed infantry battalions and cavalry squadrons to the insurrection cause.

Guanajuato. At center: the Alhóndiga de Granaditas

The Spaniards saw that it was important to defend the Alhóndiga de Granaditas public granary in Guanajuato, which maintained the flow of water, weapons, food and ammunition to the Spanish Royal Army. The insurgents entered Guanajuato and proceeded to lay siege to the Alhóndiga. The insurgents suffered heavy casualties until Juan Jose de los Reyes, the Pípila, fitted a slab of rock on his back to protect himself from enemy fire and crawled to the large wooden door of the Alhóndiga with a torch in hand to set it on fire. With this stunt, the insurgents managed to bring down the door and enter the building and overrun it. Hidalgo headed to Valladolid (now Morelia), which was captured with little opposition. While the Insurgent Army was, by then, over 60,000 strong, it was mostly formed of poorly armed men with arrows, sticks and tillage tools – it had a few guns, which had been taken from Spanish stocks.

In Aculco, the Royal Spanish forces under the command of Felix Maria Calleja, Count of Calderón, and Don Manuel de Flon (and comprising 200 infantrymen, 500 cavalry and 12 cannons) defeated the insurgents, who lost many men as well as the artillery they had obtained at Battle of Monte de las Cruces. On 29 November 1810, Hidalgo entered Guadalajara, the capital of Nueva Galicia, where he organized his government and the Insurgent Army; he also issued a decree abolishing slavery.

At Calderon Bridge (Puente de Calderón) near the city of Guadalajara Jalisco, insurgents held a hard-fought battle with the royalists. During the fierce fighting, one of the insurgents' ammunition wagons exploded, which led to their defeat. The insurgents lost all their artillery, much of their equipment and the lives of many men.

Constitutional decree for the freedom of the Mexican America

Army of the Three Guarantees enters Mexico city on 27 September 1821.

At the Wells of Baján (Norias de Baján) near Monclova, Coahuila, a former royalist named Ignacio Elizondo, who had joined the insurgent cause, betrayed them and seized Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama, José Mariano Jiménez and the rest of the entourage. They were brought to the city of Chihuahua where they were tried by a military court and executed by firing squad on 30 July 1811. Hidalgo's death resulted in a political vacuum for the insurgents until 1812. Meanwhile, the royalist military commander, General Félix María Calleja, continued to pursue rebel troops. The fighting evolved into guerrilla warfare.

The next major rebel leader was the priest José María Morelos y Pavón, who had formerly led the insurgent movement alongside Hidalgo. Morelos fortified the port of Acapulco and took the city of Chilpancingo. Along the way, Morelos, was joined by Leonardo Bravo, his son Nicholas and his brothers Max, Victor and Miguel Bravo.

Morelos conducted several campaigns in the south, managing to conquer much of the region as he gave orders to the insurgents to promote the writing of the first constitution for the new Mexican nation: the Constitution of Apatzingan, which was drafted in 1814. In 1815, Morelos was apprehended and executed by firing squad. His death concluded the second phase of the Mexican War for Independence. From 1815 to 1820, the independence movement became sluggish; it was briefly reinvigorated by Francisco Javier Mina and Pedro Moreno, who were both quickly apprehended and executed.

It was not until late 1820, when Agustín de Iturbide, one of the most bloodthirsty enemies of the insurgents, established relations with Vicente Guerrero and Guadalupe Victoria, two of the rebel leaders. Guerrero and Victoria supported Iturbide's plan for Mexican independence, El Plan de Iguala and Iturbide was appointed commander of the Ejército Trigarante, or The Army of the Three Guarantees. With this new alliance, they were able to enter Mexico City on 27 September 1821, which concluded the Mexican War for Independence.

Pastry War

French blockade in 1838

The Pastry War was the first French intervention in Mexico. Following the widespread civil disorder that plagued the early years of the Mexican republic, fighting in the streets destroyed a great deal of personal property. Foreigners whose property was damaged or destroyed by rioters or bandits were usually unable to obtain compensation from the government, and began to appeal to their own governments for help.

In 1838, a French pastry cook, Monsieur Remontel, claimed that his shop in the Tacubaya district of Mexico City had been ruined in 1828 by looting Mexican officers. He appealed to France's King Louis-Philippe (1773–1850). Coming to its citizen's aid, France demanded 600,000 pesos in damages. This amount was extremely high when compared to an average workman's daily pay, which was about one peso. In addition to this amount, Mexico had defaulted on millions of dollars worth of loans from France. Diplomat Baron Deffaudis gave Mexico an ultimatum to pay, or the French would demand satisfaction. When the payment was not forthcoming from president Anastasio Bustamante (1780–1853), the king sent a fleet under Rear Admiral Charles Baudin to declare a blockade of all Mexican ports from Yucatán to the Rio Grande, to bombard the Mexican fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, and to seize the port of Veracruz. Virtually the entire Mexican Navy was captured at Veracruz by December 1838. Mexico declared war on France.

With trade cut off, the Mexicans began smuggling imports into Corpus Christi, Texas, and then into Mexico. Fearing that France would blockade Texan ports as well, a battalion of men of the Republic of Texas force began patrolling Corpus Christi Bay to stop Mexican smugglers. One smuggling party abandoned their cargo of about a hundred barrels of flour on the beach at the mouth of the bay, thus giving Flour Bluff its name. The United States, ever watchful of its relations with Mexico, sent the schooner Woodbury to help the French in their blockade. Talks between the French Kingdom and the Texan nation occurred and France agreed not to offend the soil or waters of the Republic of Texas. With the diplomatic intervention of the United Kingdom, eventually President Bustamante promised to pay the 600,000 pesos and the French forces withdrew on 9 March 1839.

U.S. invasion

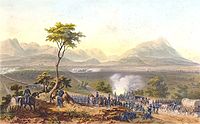

Battle of Monterrey

The U.S. occupation of Mexico City

General and President Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1852

U.S. territorial expansion under Manifest Destiny in the 19th century had reached the banks of the Rio Grande, which prompted Mexican president José Joaquín de Herrera to form an army of 6,000 men to defend the Mexican northern frontier from the expansion of the neighboring country. In 1845, Texas, a former Mexican territory that had broken away from Mexico by rebellion, was annexed into the United States. In response to this, the minister of Mexico in the U.S., Juan N. Almonte called for his Letters of Recognition and returned to Mexico; hostilities promptly ensued. On 25 April 1846, a Mexican force under colonel Anastasio Torrejon surprised and defeated a U.S. squadron at the Rancho de Carricitos in Matamoros in an event that would latter be known as the Thornton Skirmish; this was the pretext that U.S. president James K. Polk used to persuade the U.S. congress into declaring a state of war against Mexico on 13 May 1846. U.S. Army captain John C. Frémont, with about sixty well-armed men, had entered the California territory in December 1845 before the war had been official and was marching slowly to Oregon when he received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent; thus began a chapter of the war known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

On 20 September 1846, the U.S. launched an attack on Monterrey, which fell after 5 days. After this U.S. victory, hostilities were suspended for 7 weeks, allowing Mexican troops to leave the city with their flags displayed in full honors as U.S. soldiers regrouped and regained their losses. In August 1846, Commodore David Conner and his squadron of ships were in Veracruzian waters; he tried, unsuccessfully, to seize the Fort of Alvarado, which was defended by the Mexican Navy. The Americans were forced to relocate to Antón Lizardo. In confronting resistance and fortifications at the port of Veracruz, the U.S. Army and Marines implemented an intense bombardment of the city from 22–26 March 1847, causing about five hundred civilian deaths and significant damage to homes, buildings, and merchandise. General Winfield Scott and Commodore Matthew C. Perry capitalized on this civilian suffering: by refusing to allow the consulates of Spain and France to assist in civilian evacuation, they pressed Mexican Gen. Juan Morales to negotiate surrender.

U.S. commodore Matthew C. Perry, who had already captured the town of Frontera, in Tabasco, tried to seize San Juan Bautista (modern Villahermosa), but he was repelled three times by a Mexican garrison of just under three hundred men. U.S. troops were also sent to the California territories with the intention of seizing it. After squads of U.S. troops occupied the City of Los Angeles, Mexican authorities were forced to move to Sonora; but, by the end of September 1846, commander José María Flores was able to gather 500 Mexicans and managed to defeat the U.S. garrison at Los Angeles and then sent detachments to Santa Barbara and San Diego.

After putting up a fierce defense against the U.S. invasion, the Mexican positions along the state of Chihuahua began to fall. These forces had been organized by general José Antonio de Heredia and governor Ángel Trías Álvarez. The cavalry of the latter made several desperate charges against the U.S. that nearly achieved victory, but his inexperience in fighting was evident and, in the end, all the positions gained were lost.

French Intervention

Soldiers of the Mexican Army c1862.

The Battle of Puebla, Cinco de Mayo 1862, an important victory for Mexican forces against the French

The French intervention was an invasion by an expeditionary force sent by the Second French Empire, supported in the beginning by the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Spain. It followed President Benito Juárez's suspension of interest payments to foreign countries on 17 July 1861, which angered Mexico's major creditors: Spain, France and Britain.

Napoleon III of France was the instigator: His foreign policy was based on a commitment to free trade. For him, a friendly government in Mexico provided an opportunity to expand free trade by ensuring European access to important markets, and preventing monopoly by the United States. Napoleon also needed the silver that could be mined in Mexico to finance his empire. Napoleon built a coalition with Spain and Britain at a time the U.S. was engaged in a full-scale civil war. The U.S. protested, but could not intervene directly until its civil war was over in 1865.[9]

Monument to General Ignacio Zaragoza, hero of the Battle of Puebla, Cinco de Mayo 1862.

The three powers signed the Treaty of London on 31 October, to unite their efforts to receive payments from Mexico. On 8 December, the Spanish fleet and troops from Spanish-controlled Cuba arrived at Mexico's main Gulf port, Veracruz. When the British and Spanish discovered that the French planned to invade Mexico, they withdrew.

The subsequent French invasion resulted in the Second Mexican Empire, which was supported by the Roman Catholic clergy, many conservative elements of the upper class, and some indigenous communities. The presidential terms of Benito Juárez (1858–71) were interrupted by the rule of the Habsburg monarchy in Mexico (1864–67). Conservatives, and many in the Mexican nobility, tried to revive the monarchical form of government (see: First Mexican Empire) when they helped to bring to Mexico an archduke from the Royal House of Austria, Maximilian Ferdinand, or Maximilian I of Mexico (who married Charlotte of Belgium, also known as Carlota of Mexico), with the military support of France. France had various interests in this Mexican affair, such as seeking reconciliation with Austria, which had been defeated during the Franco-Austrian War, counterbalancing the growing U.S. power by developing a powerful Catholic neighbouring empire, and exploiting the rich mines in the north-west of the country.

Mexican Republican forces

In 1861, the Mexican Republican Army consisted of ten regular line battalions each of eight companies, and six line cavalry regiments, each of two squadrons. With six batteries of field artillery plus engineers, train and garrison units, the regular army numbered about 12,000 men. Auxiliary forces, comprising state militias and National Guards, provided a further 25 infantry battalions and 25 cavalry squadrons plus some garrison and artillery units. The National Guard of the Federal District of Mexico City amounted to six infantry battalions plus one each of cavalry and artillery. The newly raised corps of Rurales, created on 5 May 1861 as a mounted gendarmerie, numbered 2,200 and served as dispersed units of light cavalry against the French.[10]

General and President Porfirio Díaz, another hero of the Battle of Puebla and president of Mexico in the late nineteenth century until the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution

While opposed by substantial forces of French regular troops plus Mexican Imperial forces and contingents of foreign volunteers, the Republican Army remained in being as an effective force after the fall of Mexico City in 1863. By 1865 Liberal opposition was being led by a core of 50,000 regular Mexican troops and state National Guards, augmented by approximately 10,000 guerrillas.[11]

Díaz era

Following the French withdrawal and the overthrow of the Imperial regime of Maximilian, the Mexican Republic was re-established in 1867. In 1876, Porfirio Diaz, a leading general of the anti-Maximilianist forces, became president. He was to retain power until 1910, with only one short break. During this period of extended rule, Diaz relied essentially on military power to remain in office. He accordingly undertook a series of reforms intended to modernize the Mexican Army,[12] while at the same time terminating the historic pattern of local commanders attempting to seize power using irregulars or provincial forces.[13] Generals of the Federal Army were frequently transferred, the large officer corps was kept loyal through opportunities for graft, an efficient mounted police force of rurales took over responsibility for public order,[14] and the army itself was reduced in size. By 1910, the army numbered about 25,000 men, largely conscripts of Indian origin officered by 4,000 white middle-class officers. While generally well equipped, the Federal Army under Diaz was too small in numbers to offer effective opposition to the revolutionary forces led by Francisco Madero.[15]

Mexican Revolution 1910–1920

General Victoriano Huerta, who overthrew civilian President Francisco I. Madero in 1913

Revolutionary General Alvaro Obregón, later president of Mexico

The ouster of Porfirio Díaz saw Francisco I. Madero: a member of a rich landowning family, elected as President of Mexico. Madero kept the Federal Army intact, despite the fact that it had been outmaneuvered by the revolutionary forces that brought him to power. General Victoriano Huerta overthrew Madero in a bloody February 1913 coup. Forces opposed to the Huerta regime united against him, particularly the Constitutionalists in the north. These were led by a civilian, Venustiano Carranza as "First Chief," commanding forces led by a number of generals, but most prominently Alvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa. In the Morelos region, an intense guerrilla warfare was waged by forces led by Emiliano Zapata. The Federal Army supporting Huerta was defeated at the Battle of Zacatecas and finally disbanded in 1914[16]and a new Government army was created from Obregón's Constitutionalist forces. Zapata was assassinated in 1919; Villa was bought off and took up civilian life in northern Mexico, before being assassinated in 1923. During the post-military phase following 1920, a number of Constitutionalist leaders became presidents of Mexico: Alvaro Obregón (1920–1924), Plutarco Elías Calles (1924–28), Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940), and Manuel Avila Camacho (1940–1946). When Lázaro Cárdenas reorganized the political party founded by Plutarco Elías Calles, he created sectoral representation of groups in Mexico, one of which was the Mexican Army. In the subsequent reorganization of the party, which took place in 1946, the Institutional Revolutionary Party no longer had a separate sector for the army. No military man has been president of Mexico after 1946.

Contemporary era

General Lázaro Cárdenas, who as president of Mexico 1934–1940 brought the Mexican military under civilian control

Post-revolutionary period

Mexican soldiers on parade in Mexico's independence day parade in 2009, Mexico DF, carrying Mexican FX-05 Xiuhcoatl (Fire Serpent) assault rifles.

The ending of the Diaz regime saw a resurgence of numerous local forces led by revolutionary generals. In 1920, more than 80,000 Mexicans were under arms, with only a minority forming part of regular forces obedient to a central authority. During the 1920s, the new government demobilized the revolutionary bands, reopened the Colegio Militar (Military Academy), established the Escuela Superior de Guerra (Staff College), and raised the salaries and improved the conditions of service of the rank and file of the regular army. In spite of an abortive general's revolt in 1927, the result was a professional army obedient to the central government. During the 1930s, the political role of the officer corps was reduced by the governing Revolutionary Party and a workers' militia was established, outnumbering the regular army by two to one. By the end of World War II, the Mexican Army had become a strictly professional force focused on national defense rather than political involvement.[17]

Mexican Drug War

Although violence between drug cartels has been occurring long before the war began, the government held a generally passive stance regarding cartel violence during the 1990s and the early years of the 21st century. That changed on 11 December 2006, when newly elected President Felipe Calderón sent 6,500 federal troops to the state of Michoacán to end drug violence there. This action is regarded as the first major retaliation made against the cartel violence, and is generally viewed as the starting point of the war between the government and the drug cartels.[18] As time progressed, Calderón continued to escalate his anti-drug campaign, in which there are now about 45,000 troops involved along with state and federal police forces.

In recent times, the Mexican military has largely participated in efforts against drug trafficking. The Operaciones contra el narcotrafico (Operations against drug trafficking), for example, describes its purpose in regards to "the performance of the Mexican Army and Air Force in the permanent campaign against the drug trafficking is sustained properly in the duties that the Executive of the Nation grants to the armed forces", for according to Article 89, Section VI of the Constitution of the Mexican United States, it is the duty of the President of the Republic of the United Mexican States, as Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, to ensure that the Mexican Armed Forces perform its mandate of national security within and outside the state borders.

Military Organization in the Modern Era

Mexican Air Force cadets march during the Mexican Independence day military parade in Mexico City on 27 July 2012.

The Army is under the authority of the National Defense Secretariat or SEDENA. It has three components: a national headquarters, territorial commands, and independent units. The Minister of Defense commands the Army via a centralized command system and many general officers. The Army uses a modified continental staff system in its headquarters. The Mexican Air Force is a branch of the Mexican Army. Recruitment of personnel happens from ages 18 through 21 if secondary education was finished, 22 if High school was completed. Recruitment after age 22 is impossible in the regular army; only auxiliary posts are available. As of 2009, starting salary for Mexican army recruits was $6,000 Mexican pesos (US$500) a month with a lifetime $10,000 peso (approximately US$833) monthly pension for widows of soldiers killed in action.[19]

The principal units of the Mexican army are nine infantry brigades and a number of independent regiments and infantry battalions. The main maneuver elements of the army are organized in three corps, each consisting of three to four infantry brigades (plus other units), all based in and around the Federal District. Distinct from the brigade formations, independent regiments and battalions are assigned to zonal garrisons (52 in total) in each of the country's 12 military regions. Infantry battalions, composed of approximately 300–350 troops, generally are deployed in each zone, and certain zones are assigned an additional motorized cavalry regiment or an artillery regiment.[20]

Regional command

Cadets of the Heroic Military Academy (Mexico) with a golden eagle (September 2004).

Every afternoon, a Mexican Army platoon lowers the monumental flag in Constitution Square or Zócalo

México is divided into twelve Military Regions composed of forty-four subordinate Military Zones [the 2007 ed. of the IISS lists 12 regions, 45 zones]. Operational needs determine how many zones are in each region, with corresponding increases and decreases in troop strength.

Usually on the secretary of defence's recommendation, the senior zone commander is also the commander of the military region containing the military zone. A military zone commander has jurisdiction over every unit operating in his territory, including the Rurales (Rural Defense Force) that occasionally have been a Federal political counterweight to the power of state governors. Zone commanders provide the national defence secretary with socio-political conditions intelligence about rural areas. Moreover, they traditionally have acted in co-ordination with the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA) on planning and resources deployment.

| Military Region | Headquarter city | States in Region |

|---|---|---|

| I | México, D.F. | Distrito Federal, Hidalgo, Estado de México, Morelos |

| II | Mexicali, Baja California | Baja California, Baja California Sur, Sonora |

| III | Mazatlán, Sinaloa | Sinaloa, Durango |

| IV | Monterrey, Nuevo León | Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas |

| V | Guadalajara, Jalisco | Aguascalientes, Colima, Jalisco, Nayarit, Zacatecas |

| VI | Veracruz, Veracruz | Puebla, Tlaxcala, central and northern Veracruz |

| VII | Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas | Chiapas, Tabasco |

| VIII | Ixcotel, Oaxaca | Oaxaca, southern Veracruz |

| IX | Cumbres de Llano Largo, Guerrero | Guerrero |

| X | Mérida, Yucatán | Campeche, Quintana Roo, Yucatán |

| XI | Torreón, Coahuila | Chihuahua, Coahuila |

| XII | Irapuato, Guanajuato | Guanajuato, Michoacán, Querétaro |

- Military Zones

|

Tactical units

Mexican Paratroopers (March 2009).

The primary units of the Mexican army are ten brigades and a number of independent regiments and infantry battalions.

The Brigades, all based in and around Mexico City and its metropolitan area, are the only real maneuver elements in the army. With their support units, they are believed to account for over 40 percent of the country's ground forces. According to The Military Balance, published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the army has 10 active brigades: one armored, two infantry, one motorized infantry, one airborne, one combat engineer, three military police (the 1st and 2nd, plus the 4th MP Brigade, raised 2015), and the Presidential Guard Brigade – the latter includes a reaction group, (grupo de reaccion inmediata y potente, G.R.I.P.), whose members are trained in martial arts such as karate, aikijutsu, tae kwon do, kick boxing, kung fu, judo, and silat; furthermore, they are trained in techniques and tactics in order to protect high-ranking officials and civil servants, such as the President. The Third military police brigade was transferred to the Federal Preventive Police in 2008. The armored brigade is one of two new brigades formed since 1990 as part of a reorganization made possible by an increase in overall strength of about 25,000 troops. The brigade consists of three armored regiments and one of mechanized infantry. Each of the two infantry brigades consists of three infantry battalions and an artillery battalion. The motorized infantry brigade is composed of three motorized infantry regiments. The airborne brigade consists of two army battalions, one air force battalion and one Naval Infantry battalion. The elite Presidential Guard Brigade reports directly to the Office of the President and is responsible for providing military security for the president and for visiting dignitaries. The Presidential Guard consists of three infantry battalions, two MP battalions, one special forces battalion, one artillery battalion and one cavalry squadron. The 5 brigades together form the First Army Corps (1er Cuerpo de Ejercito).

Distinct from the brigade formations are independent regiments (all regiments are battalion sized) and battalions assigned to zonal garrisons. These independent units consist of the following:

- 109 infantry battalions (with more being planned for activation)

- 15 Mechanized infantry regiments

- 32 Armored Cavalry regiments

- 20 Armored Reconnaissance Regiments

- 24 Field Artillery regiments

- 10 Field Artillery Gun battalions, and

- 6 Mortar Artillery battalions

- plus est. 16 military police battalions

Infantry battalions are small, each of approximately 300 troops, and are generally deployed in each zone. Certain zones are also assigned a light armored cavalry regiment, mechanized infantry regiment or one of the 24 field artillery regiments and 10 field artillery battalions. Smaller detachments are often detailed to patrol more inaccessible areas of the countryside, helping to maintain order and resolve disputes.

Special Forces Corps

The Army has a Special Forces Corps unified command with 3 Special Forces Brigades, a High Command GAFE group, a GAFE group assigned to the Airborne Brigade, 74 independent Special Forces Battalions and 36 Amphibious Special Forces Groups.

The Special Forces Brigades consist of nine SF battalions. The 1st Brigade has the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Battalions; the 2nd Brigade has the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Battalions; and the 3rd Brigade has the 4th and 9th Battalions and a Rapid Intervention Force group.

The High Command GAFE is a group with no more than 100 members and is specially trained in counter-terrorist tactics. They receive orders directly from the President of Mexico.

The Amphibious Special Forces Groups are trained in amphibious warfare, they give the army extended force to the coastal lines.

Special Operations Forces

| Name | Headquarters | Structure and purpose |

|---|---|---|

Cuerpo de Fuerzas Especiales (Special Forces Corps) | Classified | |

Grupo Aeromóvil de Fuerzas Especiales del Alto Mando (High Command Airmobil Group Special Forces) | Classified | |

Grupos Anfibios de Fuerzas Especiales (Amphibious Special Forces Group) | Classified | The Amphibious Special Forces Groups allow the army to extend their operations of ground troops in the coastal and inland waters, in close coordination with the Mexican Navy. 36 battalion-sized formations are in service today. |

Estado Mayor Presidencial

Seal of the Estado Mayor Presidencial.

The Estado Mayor Presidencial (Presidential Guard) is a specific agency of the Mexican Army that is responsible for the safety and well being of the President in the practice of all of the activities of his office. On 24 March 1985 President Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado reformed the regulation of the presidential guard and published it in the Official Gazette of the Federation (Diario Oficial de la Federación) on 4 April 1986. In this version the responsibilities of this agency included assisting the President in obtaining general information, planning the President's activities under security and preventive measures for his safety. This regulation was in force during the administrations of Carlos Salinas de Gortari and Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de Leon. On 16 January 2004 during the administration of President Vicente Fox Quesada a new regulation of the Presidential Guard was issued and published by the Official Gazette of the Federation on 23 January of that same year. This ordinance updated the structure, organization and operation of the Presidential guard as a technical military body and administrative unit of the Presidency to facilitate the implementation of the powers of his office.[21][22]

Paratrooper Corps

Brigada de Fusileros Paracaidistas (Parachute Rifle Brigade) is a three-battalion paratrooper unit created in 1969 within the Mexican Army but utilizing aircraft from the Air Force. Its headquarters is in Mexico City and its training takes place in the Centro de Adiestramiento de Paracaidismo (Airborne Training Center). A battalion can be deployed rapidly to any part of the country.

Ranks

| Generales | Jefes | Oficiales | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Rank | Secretario de la Defensa Nacional | General de División | General de Brigada | General Brigadier | Coronel (Infantry) | Teniente Coronel (Infantry) | Mayor (Infantry) | Capitán Primero (Infantry) | Capitán Segundo (Infantry) | Teniente (Infantry) | Subteniente (Infantry) | |

Rank badges have a band of colour indicating branch:

Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at the Heroic Cadets Memorial in Chapultepec Park, Mexico City. The monument was designed by architect Enrique Aragón and sculpted by Ernesto Tamaríz at the entrance to Chapultepec Park in 1952.[23]

A Mexican army UH-60 Blackhawk landing in the Zocalo, Mexico City.

- Gold: Generals

- Light Brown:

- General Staff

- Presidential Guard

- Scarlet: Infantry

- Burgundy: Artillery

- Red-Brown: Quartermaster and Materiel ("Materiales de Guerra")

- Light Orange-Brown: Transportation ("Transportes")

- Green:

- "Justicia"

- Military Police

- Blue:

- Engineers

- Signals and Communications ("Transmisiones")

- Light Blue: Cavalry

- Light Gray-Blue: Cartography

- Purple:

- Army Aviation

- Parachute Brigade

- Gray: Bands

- Light Gray: Armor

- Very light Gray: Intelligence

- Brownish Gray: Administration and Army Intendancy ("Administracion e Intendencia")

- Yellow and Light Blue:

- Medical

- Veterinary and Remount

Military Industry

Mexican Army band playing.

A Mexican Army Mi-26 heavy transport helicopter.

Mexican army Humvee on 16 September 2007 parade

Since the start of the 21st century, the Army has been steadily modernising to become competitive with the armies of other American countries[24] and have also taken certain steps to decrease spending and dependency on foreign equipment in order to become more autonomous such as the domestic production of the FX-05 rifle designed in Mexico and the commitment to researching, designing and manufacturing domestic military systems such as military electronics and body armor.[25]

The Mexican military counts on three of the following departments to fulfill the general tasks of the Army and Air Force:[26]

Dirección General de Industria Militar (D.G.I.M.) – In charge of the designing, manufacturing and maintenance of vehicles and weapons, such as the assembly of the FX-05 assault rifle and the DN series armored vehicles. On 19 July 2009, SEDENA spent 488 million pesos ($37 million U.S.) to transfer technology to manufacture the G36V German made rifle. Although it is not known if this will be manufactured as a cheaper alternative to the FX-05 meant for the army or if it is to be manufactured for military police and other law enforcement agencies such as the Federal Police. The FX-05 is planned to become the new standard rifle for the armed forces replacing the Heckler & Koch G3, so it is not yet clear what the G-36 rifles will be used for.[27] As of 2011, D.G.I.M. is in charge of assembling the Oshkosh SandCat, the modified Mexican Army version of the Sandcat is named as the DN-XI and will be presented in the Mexican Independence Day parade on September 2012.[28][29]

Dirección General de Fábricas de Vestuario y Equipo (D.G.FA.V.E.) (General Directorate of Clothing and Equipment Manufacturing) – Since its creation, the department has grown from a simple clothing factory to an Industrial complex in charge of the supply and design of the Army/Air Force's uniform, shoes/boots, combat helmet and ballistic vest. Until the mid-2000s, the Mexican army's standard combat uniform color was olive green. The army then switched to all woodland camouflage and Desert Camouflage Uniform. In July 2008, the D.G.FA.V.E. announced plans for creating the country's first digital uniforms, which would consist of Woodland/jungle and Desert camouflage; these uniforms entered service in 2009.[30]

Granjas Militares (Military farms) – In charge of Agriculture; crop cultivation is a necessity to maintain the health and economy of the Army/Air Force. The Mexican Army has four established SEDENA farms:[31]- Granja SEDENA number 1 (San Juan del Río, Querétaro).

- Granja SEDENA number 2 (Ixtepec, Oaxaca).

- Granja SEDENA number 3 (Sarabia, Guanajuato).

- Granja SEDENA number 4 (La Fuente, Aguascalientes).

Modern equipment of the Mexican Army

New Mexican army uniform

Vehicles

Mexican Army ERC 90 F1 Lynx during the Independence day Parade.

VCR-TT 6X6 APC on Madero Street in downtown Mexico City after Independence Day celebrations

Mexican cavalry

| Vehicle/System | Type | Versions | Origin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Armored fighting vehicles | |||||

Armored vehicles | |||||

| Panhard ERC 90 | Armored Reconnaissance Vehicle | ERC 90 F1 Lynx | |||

Panhard VCR[32] | Armored Personnel Carrier | VCR-TT | |||

| Véhicule Blindé Léger | Armored all-terrain vehicle | VBL MILAN | |||

Oshkosh Sand Cat[28][33][34] | Armored Personnel Vehicle | Sand Cat – 245 Sandcats were delivered and have Type IV level Armored protection[35] | |||

| DN-XI | Armored Personnel Vehicle | The DN-XI is a Mexican modified & designed version of the Oshkosh Sandcat. 100 on order.[36] 1,000 to be acquired by 2018.[37] | |||

| M8 Greyhound | Armored Personnel Vehicle | Small numbers modernized | |||

Tracked armored vehicles | |||||

| Sedena-Henschel HWK-11 | Infantry fighting vehicle | HWK-11 | |||

| AMX-VCI | Armored Personnel Carrier | DNC-1: upgraded by SEDENA | |||

Infantry transport vehicles | |||||

Humvee[38] | Light Utility Vehicle | HMMWV | |||

| Chevrolet Silverado | Light Utility Vehicle | GMT900 | |||

| Ford F-Series | Light Utility Vehicle | F-150 | |||

| Dodge Ram | Light Utility Vehicle | Variants of 4x4 and 6x6 | |||

| Yamaha Rhino | Light Utility Vehicle | Rhino | |||

| Chevrolet Cheyenne | Light Utility Vehicle | Cheyenne | |||

Trucks | |||||

| M520 Goer | Utility Vehicle | M520 | |||

| Freightliner Trucks | Utility Vehicle | M2 | |||

| M35 2-1/2 ton cargo truck | Utility Vehicle | M35 | |||

| DINA S.A. | Utility Vehicle | S-Series / D-Series | |||

| Mercedes Benz | Utility Vehicle | L-Series | |||

| Chevrolet | Utility Vehicle | Kodiak | |||

| Freightliner Trucks | satellite communications | intelligence | |||

Individual weapons

FX-05 Xiuhcoatl (Fire Serpent) assault rifle

G3A3 battle rifle

MP5

P7M13

PSG1

| Name | Caliber | Type | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heckler & Koch G3 | 7.62×51mm NATO | Battle rifle. Made under license from Heckler & Koch | |

| FX-05 Xiuhcoatl | 5.56×45mm NATO | Assault rifle | |

| Heckler & Koch HK33 | 5.56×45mm NATO | Assault rifle. Made under license from Heckler & Koch | |

| M4 carbine | 5.56×45mm NATO | Assault rifle | |

| Heckler & Koch MP5 | 9×19mm Parabellum | Submachine gun. Made under license from Heckler & Koch | |

| FN P90 | 5.7×28mm | Submachine gun[39] | |

| Heckler & Koch P7 | 9×19mm Parabellum | Pistol. Made under license from Heckler & Koch | |

| Sig Sauer P226 | 9x19mm Parabellum | Pistol | |

| Beretta 92FS | 9×19mm Parabellum | Pistol | |

| FN Five-seveN | 5.7×28mm | Pistol | |

HK PSG1 Morelos Bicentenario | 7.62×51mm NATO | Sniper rifle. Made under license from Heckler & Koch | |

| Barrett M82 | .50 BMG | Sniper rifle | |

| FN Minimi | 5.56×45mm NATO | Machine gun | |

| Heckler & Koch HK21 | 7.62×51mm NATO | Machine gun. Made under license from Heckler & Koch | |

| Rheinmetall MG 3 | 7.62×51mm NATO | Machine gun. Made under license from Rheinmetall | |

| M2 Browning machine gun | .50 BMG | Machine gun | |

| M-134 minigun | 7.62×51mm NATO | Gatling-type machine gun | |

| Mk 19 | 40×53mm | Grenade machine gun | |

| Milkor MGL | 40×46mm | Grenade launcher | |

| M203 grenade launcher | 40×46mm | Grenade launcher | |

| Heckler & Koch AG-C/GLM | 40×46mm | Grenade launcher | |

| Mondragón F-08 | 7×57mm Mauser | automatic rifle used for ceremonial occasions | |

| Winchester Model 54 | 7.62×51mm | Bolt-action rifle | |

| CornerShot | Weapon accessory | ||

| Remington 870 | 12 gauge | gauge pump-action shotgun | |

| M1014 | 12 gauge | semi automatic shotgun |

Artillery

| Name | Type | Versions | Origin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Self-propelled artillery | |||||

| SDN Humvee | Self-propelled artillery | 106mm | |||

Towed artillery | |||||

| M101 | Towed howitzer | 105mm | |||

| OTO Melara Mod 56 | Towed howitzer | 105mm | |||

| M90 Norinco | Towed howitzer | 105mm | |||

| Mortier 120mm Rayé Tracté Modèle F1 | Heavy mortar | 120mm | |||

| M29 mortar | Medium mortar | 81mm | |||

| Brandt 60 mm LR Gun-mortar | Light mortar | 60mm | |||

| Mortero | Light mortar | 60mm | |||

| Oerlikon 35 mm twin cannon | Towed anti-aircraft artillery | 35mm | |||

| M114 | Howitzer | 155mm | |||

Anti-armor weapons

RPG-29 Rocket propelled grenade

MILAN

| Name | Type | Versions | Origin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Light anti-tank weapons | |||||

| Carl Gustaf recoilless rifle | multi-role recoilless rifle | 84mm | |||

| RL-83 Blindicide | light anti-tank rocket | 83mm | |||

| SMAW | anti-tank rocket | 105mm | |||

RPG-29[40] | anti-tank rocket | 105mm | |||

Anti-armor Recoilless rifles | |||||

| M40 106 mm recoilless rifle | anti-tank gun | 106mm | |||

Anti-tank guided missiles | |||||

| MILAN | Anti-tank guided missile | ||||

Future

On 16 May 2014, The Mexican government sent a request to the U.S. State Department for the purchase of 3,335 M1152 HMMWVs.[41] The Mexican government also sent a purchase request to the U.S. in late June for the sale of 18 UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters.[42]

See also

- Mexican Navy

- Mexican Air Force

Further reading

Colonial era

- Archer, Christon I. The Army in Bourbon Mexico, 1760–1810. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1977.

- Archer, Christon I. "The Officer Corps in New Spain: the Martial Career, 1759–1821." Jahrbuch für Geschicte von Staat, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Lateinamerikas 19 (1982).

- McAlister, Lyle. The "Fuero Militar" in New Spain, 1764–1800. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1957.

Post-Independence

- Camp, Roderic Ai. Generals in the Palacio: The Military in Modern Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press 1992.

- Díaz Díaz, Fernando. Caudillos y caciques: Antonio López de Santa Anna y Juan Alvarez. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1972.

- Fowler, Will. Military Political Identity and Reformism in Independent Mexico: An Analysis of the Memorias de Guerra (1821–1855). London: Institute of Latin American Studies 1996.

- Lieuwen, Edwin. Mexican Militarism: The Political Rise and Fall of the Revolutionary Army. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1968.

Neufeld, Stephen B. The Blood Contingent: The Military and the Making of Modern Mexico, 1876–1911. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2017.

- Ronfeldt, David, editor. The Modern Mexican Military: A Reassessment. La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California San Diego 1984.

- Serrano, Mónica. "The Armed Branch of the State: Civil-Military Relations in Mexico," Journal of Latin American Studies 27 (1995)

- Vanderwood, Paul. Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1981.

- Wager, J. Stephen. The Mexican Military: Approaches to the 21st Century: Coping with a New World Order. Carlisle PA: Strategic Studies Institute: U.S. Army War College 1994.

References

^ 19 de febrero.- Día del Ejército Mexicano. (in Spanish)

^ Sola, Bertha. "Día de los Niños Héroes (in Spanish). esmas.com.

^ "Country Profile: Mexico" (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. July 2008. p. 25. Retrieved 5 April 2010..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

^ Pohl, John M. D. Aztec, Mixtec and Zapotec Armies. p. 9. ISBN 1-85532-159-9.

^ "Los Origenes" (in Spanish). Secretaria De La Defensa Nacional.

^ Bueno, Jose Maria. Tropas Virreynales (1) Nueva Espana, Yucatan Y Luisiana. pp. 62–63. ISBN 84-398-0086-X.

^ Chartrand, Rene. The Spanish Army in North America 1700-1793. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-84908-597-7.

^ Bueno, Jose Maria. Tropas Virreynales (1) Nueva Espana, Yucatan Y Luisiana. pp. 35 & 38. ISBN 84-398-0086-X.

^ Michele Cunningham, Mexico and the Foreign Policy of Napoleon III (2001)

^ Rene Chartrand, page 9, "The Mexican Adventure 1861–67,

ISBN 1 85532 430 X

^ Rene Chartrand, page 11, "The Mexican Adventure 1861–67,

ISBN 1 85532 430 X

^ Meyer, Michael C. The Oxford History of Mexico. pp. 409–410. ISBN 0-19-511228-8.

^ John Keegan, pages 470–471, "World Armies",

ISBN 0-333-17236-1

^ Meyer, Michael C. The Oxford History of Mexico. pp. 405–406. ISBN 0-19-511228-8.

^ P. Jowett & A. de Quesada, pages 27–28 ""The Mexican Revolution 1910–20,

ISBN 1 84176 989 4

^ Meyer, Michael C. The Oxford History of Mexico. pp. 450–451. ISBN 0-19-511228-8.

^ John Keegan, page 471 "World Armies",

ISBN 0-333-17236-1

^ "Mexican government sends 6,500 to state scarred by drug violence". International Herald Tribune. 11 December 2002.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Mexico" (PDF). Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ "Estado Mayor Presidencial". Presidencia.gob.mx. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ "México – Presidencia de la República | Estado Mayor Presidencial". Presidencia.gob.mx. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ Espínola, Lorenza. "Los Niños Héroes, un símbolo" (in Spanish). Comisión Organizadora de la Conmemoración del Bicentenario del inicio del movimiento de Independencia Nacional y del Centenario del inicio de la Revolución Mexicana. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

^ La Jornada. "Equipo y materiales del Ejército, obsoletos, advierte el general Galván". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

^ "Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional". Sedena.gob.mx. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ "Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional". Sedena.gob.mx. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ "Alistan compra de 4 Black Hawk para PF – El Universal – México". El Universal. 18 July 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ ab Mexico orders Oshkosh SandCats – Jane's Defence Weekly

^ Foro Modelismo :: Ver tema – Novedades en el Ejercito Mexicano. Pase de Revista 2012

^ Cambia Ejército uniformes – El Mañana – Nacional Archived 4 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional | sedena.gob.mx

^ [1] Archived 25 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Nuevos Vehiculos Oshkosh Sandcat TPV para el Ejercito – Página 3

^ Mexico's security and defense trends

^ https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/68/138 Archived 9 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Mexico starts production of first 100 indigenous 4x4 armoured vehicles DN-XI – Armyrecognition.com, 19 December 2012

^ Mexico; Army funds increase of indigenous MRAP production line – Dmilt.com, 9 September 2013

^ "grupo reforma". Elnorte.com. 6 April 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

^ "Aumentan Vigilancia Durante Desfile Militar" (in Spanish). El Siglo de Torreón. 17 October 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

^ http://www.militaryfactory.com/smallarms/detail.asp?smallarms_id=487

^ "Mexico – M1152 High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWVs) – The Official Home of the Defense Security Cooperation Agency". Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ "Mexico – UH-60M Black Hawk Helicopters – The Official Home of the Defense Security Cooperation Agency". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

External links

- Photos of the Mexican Army, National Marine and Air Force

- Secretaria de la Defensa Nacional – Fabrica de armas y equipos

- Inventario 2006

- Mexican Army Photos

- Latin American Light Weapons National Inventories

- Military Territorial Division

- Mexican Army Oshkosh Sandcat