Stan Lee

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Stan Lee | |

|---|---|

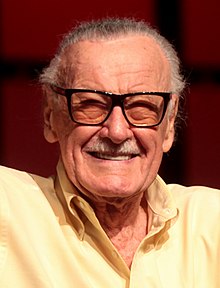

Lee in 2014 | |

| Born | Stanley Martin Lieber (1922-12-28) December 28, 1922 New York City, U.S. |

| Area(s) | Comic book writer, editor, publisher |

| Collaborators |

|

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) | Joan Boocock Lee (m. 1947; d. 2017) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

| |

therealstanlee.com | |

Stan Lee[1] (born Stanley Martin Lieber /ˈliːbər/, December 28, 1922) is an American comic-book writer, editor, film executive producer, actor, and publisher. He was formerly editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics,[2] and later its publisher[3] and chairman[4] before leaving the company to become its chairman emeritus, as well as a member of the editorial board.[5]

In collaboration with several artists, including Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, he co-created fictional characters including Spider-Man, the Hulk, Doctor Strange, the Fantastic Four, Daredevil, Black Panther, the X-Men, and, with the addition of co-writer Larry Lieber, the characters Ant-Man, Iron Man and Thor. In addition, he challenged the comics industry's censorship organization, the Comics Code Authority, indirectly leading to it updating its policies. Lee subsequently led the expansion of Marvel Comics from a small division of a publishing house to a large multimedia corporation.

He was inducted into the comic book industry's Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 1994 and the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1995. Lee received a National Medal of Arts in 2008.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Career

2.1 Early career

2.2 Marvel revolution

2.3 Later career

3 Charity work

4 Fictional portrayals

5 Film and television appearances

6 Personal life

7 Accolades

8 Bibliography

8.1 Books

8.2 Comics bibliography

8.2.1 DC Comics

8.2.2 Marvel Comics

8.2.3 Simon & Schuster

8.2.4 Other

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

Early life

Stanley Martin Lieber was born on December 28, 1922 in Manhattan, New York City,[6] in the apartment of his Romanian-born Jewish immigrant parents, Celia (née Solomon) and Jack Lieber, at the corner of West 98th Street and West End Avenue in Manhattan.[7][8] His father, trained as a dress cutter, worked only sporadically after the Great Depression,[7] and the family moved further uptown to Fort Washington Avenue,[9] in Washington Heights, Manhattan. Lee has one younger brother named Larry Lieber.[10] He said in 2006 that as a child he was influenced by books and movies, particularly those with Errol Flynn playing heroic roles.[11] By the time Lee was in his teens, the family was living in an apartment at 1720 University Avenue in The Bronx. Lee has described it as "a third-floor apartment facing out back". Lee and his brother shared the bedroom, while their parents slept on a foldout couch.[10]

Lee attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx.[12] In his youth, Lee enjoyed writing, and entertained dreams of one day writing the "Great American Novel".[13] He has said that in his youth he worked such part-time jobs as writing obituaries for a news service and press releases for the National Tuberculosis Center;[14] delivering sandwiches for the Jack May pharmacy to offices in Rockefeller Center; working as an office boy for a trouser manufacturer; ushering at the Rivoli Theater on Broadway;[15] and selling subscriptions to the New York Herald Tribune newspaper.[16] He graduated from high school early, aged 16½ in 1939, and joined the WPA Federal Theatre Project.[17]

Career

Early career

With the help of his uncle Robbie Solomon,[18] Lee became an assistant in 1939 at the new Timely Comics division of pulp magazine and comic-book publisher Martin Goodman's company. Timely, by the 1960s, would evolve into Marvel Comics. Lee, whose cousin Jean[19] was Goodman's wife, was formally hired by Timely editor Joe Simon.[n 1]

His duties were prosaic at first. "In those days [the artists] dipped the pen in ink, [so] I had to make sure the inkwells were filled", Lee recalled in 2009. "I went down and got them their lunch, I did proofreading, I erased the pencils from the finished pages for them".[21] Marshaling his childhood ambition to be a writer, young Stanley Lieber made his comic-book debut with the text filler "Captain America Foils the Traitor's Revenge" in Captain America Comics #3 (cover-dated May 1941), using the pseudonym Stan Lee,[22] which years later he would adopt as his legal name.[citation needed] Lee later explained in his autobiography and numerous other sources that he had intended to save his given name for more literary work. This initial story also introduced Captain America's trademark ricocheting shield-toss.[23]:11

He graduated from writing filler to actual comics with a backup feature, "'Headline' Hunter, Foreign Correspondent", two issues later. Lee's first superhero co-creation was the Destroyer, in Mystic Comics #6 (August 1941). Other characters he co-created during this period fans and historians call the Golden Age of Comic Books include Jack Frost, debuting in U.S.A. Comics #1 (August 1941), and Father Time, debuting in Captain America Comics #6 (August 1941).[23]:12–13

When Simon and his creative partner Jack Kirby left late in 1941, following a dispute with Goodman, the 30-year-old publisher installed Lee, just under 19 years old, as interim editor.[23]:14[24] The youngster showed a knack for the business that led him to remain as the comic-book division's editor-in-chief, as well as art director for much of that time, until 1972, when he would succeed Goodman as publisher.[2][25]

Lee entered the United States Army in early 1942 and served within the US as a member of the Signal Corps, repairing telegraph poles and other communications equipment.[26] He was later transferred to the Training Film Division, where he worked writing manuals, training films, slogans, and occasionally cartooning.[27] His military classification, he says, was "playwright"; he adds that only nine men in the US Army were given that title.[28]Vincent Fago, editor of Timely's "animation comics" section, which put out humor and funny animal comics, filled in until Lee returned from his World War II military service in 1945.

In the mid-1950s, by which time the company was now generally known as Atlas Comics, Lee wrote stories in a variety of genres including romance, Westerns, humor, science fiction, medieval adventure, horror and suspense. In the 1950s, Lee teamed up with his comic book colleague Dan DeCarlo to produce the syndicated newspaper strip, My Friend Irma, based on the radio comedy starring Marie Wilson.[29] By the end of the decade, Lee had become dissatisfied with his career and considered quitting the field.[30][31]

Marvel revolution

In the late 1950s, DC Comics editor Julius Schwartz revived the superhero archetype and experienced a significant success with its updated version of the Flash, and later with super-team the Justice League of America. In response, publisher Martin Goodman assigned Lee to come up with a new superhero team. Lee's wife suggested that he experiment with stories he preferred, since he was planning on changing careers and had nothing to lose.[30][31]

Lee acted on that advice, giving his superheroes a flawed humanity, a change from the ideal archetypes that were typically written for preteens. Before this, most superheroes were idealistically perfect people with no serious, lasting problems.[32] Lee introduced complex, naturalistic characters[33] who could have bad tempers, fits of melancholy, and vanity; they bickered amongst themselves, worried about paying their bills and impressing girlfriends, got bored or even were sometimes physically ill.

The first superhero group Lee and artist Jack Kirby created together was the Fantastic Four, based on previous Kirby superhero team Challengers of the Unknown published by DC Comics.[34] The team's immediate popularity[35] led Lee and Marvel's illustrators to produce a cavalcade of new titles. Again working with Kirby, Lee co-created the Hulk,[36]Thor,[37]Iron Man,[38] and the X-Men;[39] with Bill Everett, Daredevil;[40] and with Steve Ditko, Doctor Strange[41] and Marvel's most successful character, Spider-Man,[42] all of whom lived in a thoroughly shared universe.[43] Lee and Kirby gathered several of their newly created characters together into the team title The Avengers[44] and would revive characters from the 1940s such as the Sub-Mariner[45] and Captain America.[46]

Comics historian Peter Sanderson wrote that in the 1960s:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

DC was the equivalent of the big Hollywood studios: After the brilliance of DC's reinvention of the superhero ... in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it had run into a creative drought by the decade's end. There was a new audience for comics now, and it wasn't just the little kids that traditionally had read the books. The Marvel of the 1960s was in its own way the counterpart of the French New Wave.... Marvel was pioneering new methods of comics storytelling and characterization, addressing more serious themes, and in the process keeping and attracting readers in their teens and beyond. Moreover, among this new generation of readers were people who wanted to write or draw comics themselves, within the new style that Marvel had pioneered, and push the creative envelope still further.[47]

Lee's revolution extended beyond the characters and storylines to the way in which comic books engaged the readership and built a sense of community between fans and creators.[48] He introduced the practice of regularly including a credit panel on the splash page of each story, naming not just the writer and penciller but also the inker and letterer. Regular news about Marvel staff members and upcoming storylines was presented on the Bullpen Bulletins page, which (like the letter columns that appeared in each title) was written in a friendly, chatty style. Lee has said that his goal was for fans to think of the comics creators as friends, and considered it a mark of his success on this front that, at a time when letters to other comics publishers were typically addressed "Dear Editor", letters to Marvel addressed the creators by first name (e.g. "Dear Stan and Jack").[26] By 1967, the brand was well-enough ensconced in popular culture that a March 3 WBAI radio program with Lee and Kirby as guests was titled "Will Success Spoil Spiderman" [sic].[49]

Throughout the 1960s, Lee scripted, art-directed and edited most of Marvel's series, moderated the letters pages, wrote a monthly column called "Stan's Soapbox", and wrote endless promotional copy, often signing off with his trademark motto, "Excelsior!" (which is also the New York state motto). To maintain his workload and meet deadlines, he used a system that was used previously by various comic-book studios, but due to Lee's success with it, became known as the "Marvel Method". Typically, Lee would brainstorm a story with the artist and then prepare a brief synopsis rather than a full script. Based on the synopsis, the artist would fill the allotted number of pages by determining and drawing the panel-to-panel storytelling. After the artist turned in penciled pages, Lee would write the word balloons and captions, and then oversee the lettering and coloring. In effect, the artists were co-plotters, whose collaborative first drafts Lee built upon. Lee recorded messages to the newly formed Merry Marvel Marching Society fan club in 1965.[50]

Following Ditko's departure from Marvel in 1966, John Romita Sr. became Lee's collaborator on The Amazing Spider-Man. Within a year, it overtook Fantastic Four to become the company's top seller.[51] Lee and Romita's stories focused as much on the social and college lives of the characters as they did on Spider-Man's adventures.[52] The stories became more topical, addressing issues such as the Vietnam War,[53] political elections,[54] and student activism.[55]Robbie Robertson, introduced in The Amazing Spider-Man #51 (August 1967) was one of the first African-American characters in comics to play a serious supporting role.[56] In the Fantastic Four series, the lengthy run by Lee and Kirby produced many acclaimed storylines as well as characters that have become central to Marvel, including the Inhumans[57][58] and the Black Panther,[59] an African king who would be mainstream comics' first black superhero.[60]

The story frequently cited as Lee and Kirby's finest achievement[61][62] is the three-part "Galactus Trilogy" that began in Fantastic Four #48 (March 1966), chronicling the arrival of Galactus, a cosmic giant who wanted to devour the planet, and his herald, the Silver Surfer.[63][64]Fantastic Four #48 was chosen as #24 in the 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time poll of Marvel's readers in 2001. Editor Robert Greenberger wrote in his introduction to the story that "As the fourth year of the Fantastic Four came to a close, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby seemed to be only warming up. In retrospect, it was perhaps the most fertile period of any monthly title during the Marvel Age."[65] Comics historian Les Daniels noted that "[t]he mystical and metaphysical elements that took over the saga were perfectly suited to the tastes of young readers in the 1960s", and Lee soon discovered that the story was a favorite on college campuses.[66] Lee and artist John Buscema launched The Silver Surfer series in August 1968.[67][68]

The following year, Lee and Gene Colan created the Falcon, comics' first African-American superhero in Captain America #117 (September 1969).[69] Then in 1971, Lee indirectly helped reform the Comics Code.[70] The U. S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare had asked Lee to write a comic-book story about the dangers of drugs and Lee conceived a three-issue subplot in The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 (cover-dated May–July 1971), in which Peter Parker's best friend becomes addicted to pills. The Comics Code Authority refused to grant its seal because the stories depicted drug use; the anti-drug context was considered irrelevant. With Goodman's cooperation and confident that the original government request would give him credibility, Lee had the story published without the seal. The comics sold well and Marvel won praise for its socially conscious efforts.[71] The CCA subsequently loosened the Code to permit negative depictions of drugs, among other new freedoms.[72][73]

Lee also supported using comic books to provide some measure of social commentary about the real world, often dealing with racism and bigotry.[74] "Stan's Soapbox", besides promoting an upcoming comic book project, also addressed issues of discrimination, intolerance, or prejudice.[75][76]

In 1972, Lee stopped writing monthly comic books to assume the role of publisher. His final issue of The Amazing Spider-Man was #110 (July 1972)[77] and his last Fantastic Four was #125 (August 1972).[78]

Later career

Signed photo of Lee at the 1975 San Diego Comic-Con

In later years, Lee became a figurehead and public face for Marvel Comics. He made appearances at comic book conventions around America, lecturing at colleges and participating in panel discussions. Lee and John Romita Sr. launched the Spider-Man newspaper comic strip on January 3, 1977.[79] Lee's final collaboration with Jack Kirby, The Silver Surfer: The Ultimate Cosmic Experience, was published in 1978 as part of the Marvel Fireside Books series and is considered to be Marvel's first graphic novel.[80] Lee and John Buscema produced the first issue of The Savage She-Hulk (February 1980), which introduced the female cousin of the Hulk[81] and crafted a Silver Surfer story for Epic Illustrated #1 (Spring 1980).[82] He moved to California in 1981 to develop Marvel's TV and movie properties. He has been an executive producer for, and has made cameo appearances in Marvel film adaptations and other movies. He occasionally returned to comic book writing with various Silver Surfer projects including a 1982 one-shot drawn by John Byrne,[83] the Judgment Day graphic novel illustrated by John Buscema,[84] the Parable limited series drawn by French artist Mœbius,[85] and The Enslavers graphic novel with Keith Pollard.[86] Lee was briefly president of the entire company, but soon stepped down to become publisher instead, finding that being president was too much about numbers and finance and not enough about the creative process he enjoyed.[87]

Peter Paul and Lee began a new Internet-based superhero creation, production, and marketing studio, Stan Lee Media, in 1998.[88] It grew to 165 people and went public through a reverse merger structured by investment banker Stan Medley in 1999, but, near the end of 2000, investigators discovered illegal stock manipulation by Paul and corporate officer Stephan Gordon.[89] Stan Lee Media filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in February 2001.[90] Paul was extradited to the U.S. from Brazil and pleaded guilty to violating SEC Rule 10b-5 in connection with trading of his stock in Stan Lee Media.[91][92] Lee was never implicated in the scheme. In 2001, Lee, Gill Champion, and Arthur Lieberman formed POW! (Purveyors of Wonder) Entertainment to develop film, television and video game properties. Lee created the risqué animated superhero series Stripperella for Spike TV. In 2004 POW! Entertainment went public. Also that year, Lee announced a superhero program that would feature Ringo Starr, the former Beatle, as the lead character.[93][94] Additionally, in August of that year, Lee announced the launch of Stan Lee's Sunday Comics,[95] a short-lived subscription service hosted by Komikwerks.com. On March 15, 2007, after Stan Lee Media had been purchased by Jim Nesfield, the company filed a lawsuit against Marvel Entertainment for $5 billion, claiming Lee had given his rights to several Marvel characters to Stan Lee Media in exchange for stock and a salary.[96] On June 9, 2007, Stan Lee Media sued Lee; his newer company, POW! Entertainment; and POW! subsidiary QED Entertainment.[97][98]

In 2008, Lee wrote humorous captions for the political fumetti book Stan Lee Presents Election Daze: What Are They Really Saying?.[99] In April of that year, Brighton Partners and Rainmaker Animation announced a partnership POW! to produce a CGI film series, Legion of 5.[100] Other projects by Lee announced in the late 2000s included a line of superhero comics for Virgin Comics,[101] a TV adaptation of the novel Hero,[102] a foreword to Skyscraperman by skyscraper fire-safety advocate and Spider-Man fan Dan Goodwin,[103] a partnership with Guardian Media Entertainment and The Guardian Project to create NHL superhero mascots[104] and work with the Eagle Initiative program to find new talent in the comic book field.[105]

Lee promoting Stan Lee's Kids Universe at the 2011 New York Comic Con

In October 2011, Lee announced he would partner with 1821 Comics on a multimedia imprint for children, Stan Lee's Kids Universe, a move he said addressed the lack of comic books targeted for that demographic; and that he was collaborating with the company on its futuristic graphic novel Romeo & Juliet: The War, by writer Max Work and artist Skan Srisuwan.[106][107] At the 2012 San Diego Comic-Con International, Lee announced his YouTube channel, Stan Lee's World of Heroes, which airs programs created by Lee, Mark Hamill, Peter David, Adrianne Curry, and Bonnie Burton among others.[108][109][110][111] Lee wrote the book, Zodiac released in January 2015, with Stuart Moore.[112] The film Stan Lee's Annihilator, based on a Chinese prisoner-turned-superhero named Ming and in production since 2013, is set for a 2015 release.[113][114][115]

In his later career, Lee's contributions continued to expand outside the style that he helped pioneer. An example of this is his first work for DC Comics in the 2000s, launching the Just Imagine... series, in which Lee re-imagined the DC superheroes Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, and the Flash.[116]Manga projects involving Lee include Karakuridôji Ultimo, a collaboration with Hiroyuki Takei, Viz Media and Shueisha,[117] and Heroman, serialized in Square Enix's Monthly Shōnen Gangan with the Japanese company Bones.[118][119] In 2011, Lee started writing a live-action musical, The Yin and Yang Battle of Tao.[120]

This period also saw a number of collaborators honor Lee for his influence on the comics industry. In 2006, Marvel commemorated Lee's 65 years with the company by publishing a series of one-shot comics starring Lee himself meeting and interacting with many of his co-creations, including Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, the Thing, Silver Surfer, and Doctor Doom. These comics also featured short pieces by such comics creators as Joss Whedon and Fred Hembeck, as well as reprints of classic Lee-written adventures.[121] At the 2007 Comic-Con International, Marvel Legends introduced a Stan Lee action figure. The body beneath the figure's removable cloth wardrobe is a re-used mold of a previously released Spider-Man action figure, with minor changes.[122]Comikaze Expo, Los Angeles' largest comic book convention, was rebranded as Stan Lee's Comikaze Presented by POW! Entertainment in 2012.[123]

At the 2016 Comic-Con International, Lee introduced his digital graphic novel Stan Lee's 'God Woke',[124][125][126] with text originally written as a poem he presented at Carnegie Hall in 1972.[127] The print-book version won the 2017 Independent Publisher Book Awards' Outstanding Books of the Year Independent Voice Award.[128]

Charity work

The Stan Lee Foundation was founded in 2010 to focus on literacy, education, and the arts. Its stated goals include supporting programs and ideas that improve access to literacy resources, as well as promoting diversity, national literacy, culture and the arts.[129]

Stan Lee has donated portions of his personal effects to the University of Wyoming at various times, between 1981 and 2001.[130]

Fictional portrayals

Lee and Kirby (bottom left) as themselves on the cover of The Fantastic Four #10 (January 1963). Art by Kirby and Dick Ayers.

Stan Lee and his collaborator Jack Kirby appear as themselves in The Fantastic Four #10 (January 1963), the first of several appearances within the fictional Marvel Universe.[131] The two are depicted as similar to their real-world counterparts, creating comic books based on the "real" adventures of the Fantastic Four.

Lee was parodied by Kirby in comics published by rival DC Comics as Funky Flashman.[132] Kirby later portrayed himself, Lee, production executive Sol Brodsky, and Lee's secretary Flo Steinberg as superheroes in What If #11 (October 1978), "What If the Marvel Bullpen Had Become the Fantastic Four?", in which Lee played the part of Mister Fantastic. Lee has also made numerous cameo appearances in many Marvel titles, appearing in audiences and crowds at many characters' ceremonies and parties, and hosting an old-soldiers reunion in Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos #100 (July 1972). Lee appeared, unnamed, as the priest at Luke Cage and Jessica Jones' wedding in New Avengers Annual #1 (June 2006). He pays his respects to Karen Page at her funeral in Daredevil vol. 2, #8 (June 1998), and appears in The Amazing Spider-Man #169 (June 1977).

In 1994, artist Alex Ross rendered Lee as a bar patron on page 44 of Marvels #3.[133]

In Marvel's "Flashback" series of titles cover-dated July 1997, a top-hatted caricature of Lee as a ringmaster introduced stories that detailed events in Marvel characters' lives before they became superheroes, in special "-1" editions of many Marvel titles. The "ringmaster" depiction of Lee was originally from Generation X #17 (July 1996), where the character narrated a story set primarily in an abandoned circus. Though the story itself was written by Scott Lobdell, the narration by "Ringmaster Stan" was written by Lee, and the character was drawn in that issue by Chris Bachalo.

Lee and other comics creators are mentioned on page 479 of Michael Chabon's 2000 novel about the comics industry The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Chabon also acknowledges a debt to Lee and other creators on the book's Author's Note page.

On one of the last pages of Truth: Red, White & Black, Lee appears in a real photograph among other celebrities on a wall of the Bradley home.[134]

Under his given name of Stanley Lieber, Stan Lee appears briefly in Paul Malmont's 2006 novel The Chinatown Death Cloud Peril.[135]

In Stan Lee Meets Superheroes, which Lee wrote, he comes into contact with some of his favorite creations.[121] Stan Lee and Jack Kirby appear as professors in Marvel Adventures Spider-Man #19.

In Lavie Tidhar's 2013 The Violent Century, Lee appears – under his birth name of "Stanley Martin Lieber" – as a historian of superhumans.[136]

Film and television appearances

Lee has had cameo appearances in many Marvel film and television projects. A few of these appearances are self-aware and sometimes reference Lee's involvement in the creation of certain characters. Lee has been a credited executive producer on most Marvel film and television projects since the 1990 direct-to-video Captain America film.[137][138]

Personal life

Lee was raised in a Jewish family. In a 2002 survey of whether he believes in God, he stated, "Well, let me put it this way... [Pauses.] No, I'm not going to try to be clever. I really don't know. I just don't know."[139]

From 1945 to 1947, Lee lived in the rented top floor of a brownstone in the East 90s in Manhattan.[140] He married Joan Clayton Boocock on December 5, 1947,[141][142] and in 1949, the couple bought house at 1084 West Broadway in Woodmere, New York, on Long Island, living there through 1952.[143] Their daughter Joan Celia "J. C." Lee was born in 1950. Another child, daughter Jan Lee, died three days after delivery in 1953.[144] The Lees resided at 226 Richards Lane in the Long Island town of Hewlett Harbor, New York, from 1952 to 1980.[145] They also owned a condominium at 220 East 63rd Street in Manhattan from 1975 to 1980,[146] and, during the 1970s, a vacation home on Cutler Lane in Remsenburg, New York.[147] For their move to the west coast in 1981, he and his wife bought a home in West Hollywood, California previously owned by comedian Jack Benny's radio announcer, Don Wilson.[148]

In late September 2012, Lee underwent an operation to insert a pacemaker, cancelling planned appearances at conventions.[149][150]

On July 6, 2017, his wife of 69 years, Joan, died of complications from a stroke. She was 95 years old.[151]

Accolades

| Year | Award | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Inkpot Award[152] | Won | |

| 1994 | The Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame[153] | ||

| 1995 | Jack Kirby Hall of Fame[154] | ||

| 2002 | Saturn Award | The Life Career Award | |

| 2008 | National Medal of Arts[155] | ||

| 2009 | Hugo Award | Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation- Iron Man | Nominated |

Scream Awards[156] | Comic-Con Icon Award | Won | |

| 2011 | Hollywood Walk of Fame[157] | ||

| 2012 | Visual Effects Society Awards | Lifetime Achievement Award | |

Producers Guild of America[158] | Vanguard Award | ||

| 2017 | National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers[159] | Performance in a Comedy, Supporting |

- The County of Los Angeles declared October 2, 2009 "Stan Lee Day".[160]

- The City of Long Beach declared October 2, 2009 "Stan Lee Day".[160]

On July 14, 2017, Lee and Jack Kirby were named Disney Legends for their creation of numerous characters that would comprise Disney's Marvel Cinematic Universe.[161]

On July 18, 2017, as part of D23 Disney Legends event, a ceremony was held on TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood Boulevard where Stan Lee imprinted his hands, feet and signature in cement.[162]

Bibliography

Books

Lee, Stan; Mair, George (2002). Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2800-8..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Lee, Stan (1997) [Originally published by Simon & Schuster in 1974]. Origins of Marvel Comics. Marvel Entertainment Group. ISBN 978-0-7851-0551-0.

Lee, Stan; David, Peter (2015). Amazing, Fantastic, Incredible. Simon & Schuster.

Comics bibliography

Lee's comics work includes:[82]

DC Comics

DC Comics Presents: Superman #1 (2004)

Detective Comics #600 (1989, text piece)

Just Imagine Stan Lee creating:

Aquaman (with Scott McDaniel) (2002)

Batman (with Joe Kubert) (2001)

Catwoman (with Chris Bachalo) (2002)

Crisis (with John Cassaday) (2002)

Flash (with Kevin Maguire) (2002)

Green Lantern (with Dave Gibbons) (2001)

JLA (with Jerry Ordway) (2002)

Robin (with John Byrne) (2001)

Sandman (with Walt Simonson) (2002)

Secret Files and Origins (2002)

Shazam! (with Gary Frank) (2001)

Superman (with John Buscema) (2001)

Wonder Woman (with Jim Lee) (2001)

Marvel Comics

The Amazing Spider-Man #1–100, 105–110, 116–118, 200, Annual #1–5, 18 (1962–84); (backup stories): #634–645 (2010–11)

The Amazing Spider-Man, strips (1977–present)[163]

The Avengers #1–35 (1963–66)

Captain America #100–141 (1968–71) (continues from Tales of Suspense #99)

Daredevil, #1–9, 11–50, 53, Annual #1 (1964–69)

Daredevil, vol. 2, #20 (backup story) (2001)

Epic Illustrated #1 (Silver Surfer) (1980)

Fantastic Four #1–114, 120–125, Annual #1–6 (1961–72); #296 (1986)

The Incredible Hulk #1–6 (continues to Tales to Astonish #59)

The Incredible Hulk, vol. 2, #108–120 (1968–69)

Journey into Mystery (Thor) plotter #83–96 (1962–63), writer #97–125, Annual #1 (1963–66) (continues to Thor #126)

The Mighty Thor #126–192, 200, Annual #2 (1966–72), 385 (1987)

Nightcat #1 (1991)

Ravage 2099 #1–7 (1992–93)

Savage She-Hulk #1 (1980)

Savage Tales #1 (1971)

Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos #1–28, Annual #1 (1963–66)

Silver Surfer #1–18 (1968–70)

Silver Surfer, vol. 2, #1 (1982)

Silver Surfer: Judgment Day (1988)

ISBN 978-0-87135-427-3

Silver Surfer: Parable #1–2 (1988–89)

Silver Surfer: The Enslavers (1990)

ISBN 978-0-87135-617-8

Solarman #1–2 (1989–90)

The Spectacular Spider-Man (magazine) #1–2 (1968)

The Spectacular Spider-Man Annual #10 (1990)

Strange Tales (diverse stories): #9, 11, 74, 89, 90–100 (1951–62); (Human Torch): #101–109, 112–133, Annual #2; (Doctor Strange): #110–111, 115–142, 151–158 (1962–67); (Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.: #135–147, 150–152 (1965–67)

Tales to Astonish (diverse stories): #1, 6, 12–13, 15–17, 24–33 (1956–62); Ant-Man/Giant Man: #35–69 (1962–65) (The Hulk: #59–101 (1964–1968); Sub-Mariner: #70–101 (1965–68)

Tales of Suspense (diverse stories):#7, 9, 16, 22, 27, 29–30 (1959–62); (Iron Man): plotter #39–46 (1963), writer #47–98 (1963–68) (Captain America): #58–86, 88–99 (1964–68)

Web of Spider-Man Annual #6 (1990)

What If (Fantastic Four) #200 (2011)

The X-Men #1–19 (1963–66)

Simon & Schuster

The Silver Surfer: The Ultimate Cosmic Experience, 114 pages, September 1978,

ISBN 978-0-671-24225-1

Other

- Heroman

- How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way

- Ultimo (manga original concept)

See also

|

|

|

Notes

^ Lee's account of how he began working for Marvel's predecessor, Timely, has varied. He has said in lectures and elsewhere that he simply answered a newspaper ad seeking a publishing assistant, not knowing it involved comics, let alone his cousin Jean's husband, Martin Goodman:I applied for a job in a publishing company ... I didn't even know they published comics. I was fresh out of high school, and I wanted to get into the publishing business, if I could. There was an ad in the paper that said, "Assistant Wanted in a Publishing House." When I found out that they wanted me to assist in comics, I figured, 'Well, I'll stay here for a little while and get some experience, and then I'll get out into the real world.' ... I just wanted to know, 'What do you do in a publishing company?' How do you write? ... How do you publish? I was an assistant. There were two people there named Joe Simon and Jack Kirby – Joe was sort-of the editor/artist/writer, and Jack was the artist/writer. Joe was the senior member. They were turning out most of the artwork. Then there was the publisher, Martin Goodman... And that was about the only staff that I was involved with. After a while, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby left. I was about 17 years old [sic], and Martin Goodman said to me, 'Do you think you can hold down the job of editor until I can find a real person?' When you're 17, what do you know? I said, 'Sure! I can do it!' I think he forgot about me, because I stayed there ever since.[20]

However, in his 2002 autobiography, Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee he writes:

My uncle, Robbie Solomon, told me they might be able to use someone at a publishing company where he worked. The idea of being involved in publishing definitely appealed to me. ... So I contacted the man Robbie said did the hiring, Joe Simon, and applied for a job. He took me on and I began working as a gofer for eight dollars a week....

Joe Simon, in his 1990 autobiography The Comic Book Makers, gives the account slightly differently: "One day [Goodman's relative known as] Uncle Robbie came to work with a lanky 17-year-old in tow. 'This is Stanley Lieber, Martin's wife's cousin,' Uncle Robbie said. 'Martin wants you to keep him busy.'"

In an appendix, however, Simon appears to reconcile the two accounts. He relates a 1989 conversation with Lee:

Lee: I've been saying this [classified-ad] story for years, but apparently it isn't so. And I can't remember because I['ve] said it so long now that I believe it.

...

Simon: Your Uncle Robbie brought you into the office one day and he said, 'This is Martin Goodman's wife's nephew.' [sic] ... You were seventeen years old.

Lee: Sixteen and a half!

Simon: Well, Stan, you told me seventeen. You were probably trying to be older.... I did hire you.

References

^ Lee & Mair 2002, p. 27

^ ab Kupperberg, Paul (2006). The Creation of Spider-Man. New York, New York: Rosen Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4042-0763-9.

^ Gilroy, Dan (September 17, 1986). "Marvel Now a $100 Million Hulk: Marvel Divisions and Top Execs". Variety. p. 81. Archived from the original (jpeg) on February 14, 2012.

^ "Marvel Entertainment Group Inc. Form 10-K/A". Securities and Exchange Commission. May 15, 1997. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

^ "Stan Lee". POW! Entertainment. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

^ Miller, John Jackson (June 10, 2005). "Comics Industry Birthdays". Comics Buyer's Guide. Iola, Wisconsin. Archived from the original on October 30, 2010.

^ ab Lee & Mair 2002, p. 5

^ The Celebrity Who's Who – World Almanac. Google Books. September 1986. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-345-33990-4. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

^ Lewine, Edward (September 4, 2007). "Sketching Out His Past: Image 1". The New York Times Key Magazine. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ ab Lewine. "Image 2". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Kugel, Allison (March 13, 2006). "Stan Lee: From Marvel Comics Genius to Purveyor of Wonder with POW! Entertainment". PR.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

^ Lee and Mair, p. 17

^ Sedlmeier, Cory, ed. Marvel Masterworks: The Incredible Hulk Volume 2. Marvel Comics. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7851-5883-7.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ "Biography". StanLeeWeb.com (fan site by minority shareholders of POW! Entertainment. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Apuzzo, Jason (February 1, 2012). "With Great Power: A Conversation with Stan Lee at Slamdance 2012". Moviefone. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013.

^ "Stan Lee". WebOfStories. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

^ Lee and Mair, p. 18

^ "I Let People Do Their Jobs!': A Conversation with Vince Fago—Artist, writer, and Third Editor-in-Chief of Timely/Marvel Comics". Alter Ego. 3 (11). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. November 2001. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009.

^ Lee, Mair, p. 22

^ "Interview with Stan Lee (Part 1 of 5)". IGN FilmForce. June 26, 2000. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015.

^ Boucher, Geoff (September 25, 2009). "Jack Kirby, the abandoned hero of Marvel's grand Hollywood adventure, and his family's quest". Hero Complex (column), Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011.

^ Sanderson, Peter; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). "1940s". Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7566-4123-8.Joe Simon and Jack Kirby's assistant Stanley Lieber wrote his first story for Timely, a text story called 'Captain America Foils the Traitor's Revenge'. It was also his first superhero story, and the first work he signed using his new pen name of Stan Lee.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ abc Thomas, Roy (2006). Stan Lee's Amazing Marvel Universe. New York: Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-4225-5.With the speed of thought, he sent his shield spinning through the air to the other end of the tent, where it smacked the knife out of Haines' hand!" It became a convention starting the following issue, in a Simon & Kirby's comics story depict the following: "Captain America's speed of thought and action save Bucky's life—as he hurls his shield across the room.

^ Sanderson "1940s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 19

^ Brooks, Brad; Tim Pilcher (2005). The Essential Guide to World Comics. London, United Kingdom: Collins & Brown. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-84340-300-5.

^ ab Boatz, Darrel L. (December 1988). "Stan Lee". Comics Interview (64). Fictioneer Books. pp. 5–23.

^ Conan, Neal (October 27, 2010). "Stan Lee, Mastermind of the Marvel Universe". Talk of the Nation. National Public Radio.

^ McLaughlin, Jeff; Stan Lee (2007). Stan Lee: Conversations. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-57806-985-9.

^ Heintjes, Tom (2009). "Everybody's Friend: Remembering Stan Lee and Dan DeCarlo's My Friend Irma". Hogan's Alley. Bull Moose Publishing (16). Archived from the original on October 13, 2013.

^ ab Kaplan, Arie (2006). Masters of the Comic Book Universe Revealed!. Chicago Review Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-55652-633-6.

^ ab McLaughlin, Jeff; Stan Lee (2007). Stan Lee: Conversations. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-57806-985-9.

^ Noted comic-book writer Alan Moore described the significance of this new approach in a radio interview on the BBC Four program Chain Reaction, transcribed at "Alan Moore Chain Reaction Interview Transcript". Comic Book Resources. January 27, 2005. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010.:The DC comics were ... one dimensional characters whose only characteristic was they dressed up in costumes and did good. Whereas Stan Lee had this huge breakthrough of two-dimensional characters. So, they dress up in costumes and do good, but they've got a bad heart. Or a bad leg. I actually did think for a long while that having a bad leg was an actual character trait.

^ Wright, Bradford W. (2003). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8018-7450-5.

^ Kimball, Kirk (n.d.). "Secret Origins of the Fantastic Four". Dial B For Blog. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015.

^ DeFalco, Tom "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 84: "It did not take long for editor Stan Lee to realize that The Fantastic Four was a hit...the flurry of fan letters all pointed to the FF's explosive popularity."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 85: "Based on their collaboration on The Fantastic Four, [Stan] Lee worked with Jack Kirby. Instead of a team that fought traditional Marvel monsters however, Lee decided that this time he wanted to feature a monster as the hero."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 88: "[Stan Lee] had always been fascinated by the legends of the Norse gods and realized that he could use those tales as the basis for his new series centered on the mighty Thor...The heroic and glamorous style that...Jack Kirby [had] was perfect for Thor."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 91: "Set against the background of the Vietnam War, Iron Man signaled the end of Marvel's monster/suspense line when he debuted in Tales of Suspense #39...[Stan] Lee discussed the general outline for Iron Man with Larry Lieber, who later wrote a full script for the origin story."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 94: "The X-Men #1 introduced the world to Professor Charles Xavier and his teenage students Cyclops, Beast, Angel, Iceman, and Marvel Girl. Magneto, the master of magnetism and future leader of the evil mutants, also appeared."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 100: "Stan Lee chose the name Daredevil because it evoked swashbucklers and circus daredevils, and he assigned Bill Everett, the creator of the Sub-Mariner to design and draw Daredevil #1."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 93: [Stan Lee] decided his new superhero feature would star a magician. Since Lee was enjoying his collaborations with Steve Ditko on The Amazing Spider-Man, he decided to assign the new feature to Ditko, who usually handled at least one of the backups in Strange Tales.

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 87: "Deciding that his new character would have spider-like powers, [Stan] Lee commissioned Jack Kirby to work on the first story. Unfortunately, Kirby's version of Spider-Man's alter ego Peter Parker proved too heroic, handsome, and muscular for Lee's everyman hero. Lee turned to Steve Ditko, the regular artist on Amazing Adult Fantasy, who designed a skinny, awkward teenager with glasses."

^ Wright, p. 218

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 94: "Filled with some wonderful visual action, The Avengers #1 has a very simple story: the Norse god Loki tricked the Hulk into going on a rampage ... The heroes eventually learned about Loki's involvement and united with the Hulk to form the Avengers."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 86: "Stan Lee and Jack Kirby reintroduced one of Marvel's most popular Golden Age heroes – Namor, the Sub-Mariner."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 99: "'Captain America lives again!' announced the cover of The Avengers #4...Cap was back."

^ Sanderson, Peter (October 10, 2003). "Continuity/Discontinuity". Comics in Context (column) No. 14, IGN. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011.

^ "Marvel Bullpen Bulletins". (reprinted on fan site). Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ "Radio". The New York Times. March 3, 1967. Retrieved April 20, 2013. Abstract only; full article requires payment or subscription

^ "Audio of Merry Marvel Marching Society record". Archived from the original on December 10, 2005. Retrieved January 30, 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) , including voice of Stan Lee

^ Thomas, Roy; Sanderson, Peter (2007). The Marvel Vault: A Museum-in-a-Book with Rare Collectibles from the World of Marvel. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7624-2844-1.

^ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7566-9236-0.[Stan Lee] knew that most readers tuned in every month for a glimpse of that side of Spider-Man's life as much as they did to see the wall-crawler battle the latest supervillain.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Manning "1960s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 39: The Amazing Spider-Man #47 (April 1967) "Kraven's latest rematch with Spidey was set during a going-away party for Flash Thompson, who was facing the very real issue of the Vietnam War draft."

^ Manning "1960s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 43: The Spectacular Spider-Man #1 (July 1968) "Drawn by Romita and Jim Mooney, the mammoth 52-page lead story focused on corrupt politician Richard Raleigh's plot to terrorize the city."

^ Manning "1960s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 46: The Amazing Spider-Man #68 (January 1969) "Stan Lee tackled the issues of the day again when, with artists John Romita and Jim Mooney, he dealt with social unrest at Empire State University."

^ David, Peter; Greenberger, Robert (2010). The Spider-Man Vault: A Museum-in-a-Book with Rare Collectibles Spun from Marvel's Web. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7624-3772-6.Joseph 'Robbie' Robertson made his debut in The Amazing Spider-Man #51, in a manner that was as quiet and unassuming as the character himself. His debut wasn't treated like the landmark event that it was; he was simply there one day, no big deal.

^ Cronin, Brian (September 18, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 261". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 111: "The Inhumans, a lost race that diverged from humankind 25,000 years ago and became genetically enhanced."

^ Cronin, Brian (September 19, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 262". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 117: Stan Lee wanted to do his part by co-creating the first black super hero. Lee discussed his ideas with Jack Kirby and the result was seen in Fantastic Four #52.

^ Thomas, Stan Lee's Amazing Marvel Universe, pp. 112–115

^ Hatfield, Charles (February 2004). "The Galactus Trilogy: An Appreciation". The Collected Jack Kirby Collector. 1: 211.

^ Cronin, Brian (February 19, 2010). "A Year of Cool Comics – Day 50". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 115: "Stan Lee may have started the creative discussion that culminated in Galactus, but the inclusion of the Silver Surfer in Fantastic Four #48 was pure Jack Kirby. Kirby realized that a being like Galactus required an equally impressive herald."

^ Greenberger, Robert, ed. (December 2001). 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time. Marvel Comics. p. 26.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. Harry N. Abrams. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8109-3821-2.

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 131: "When Stan Lee was told to expand the Marvel line, he immediately gave the Surfer his own title...Since Jack Kirby had more than enough assignments, Lee assigned John Buscema the task of illustrating the new book."

^ Daniels, p. 139: "Beautifully drawn by John Buscema, this comic book represented an attempt to upgrade the medium with a serious character of whom Lee had grown very fond."

^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 137: "The Black Panther may have broken the mold as Marvel's first black superhero, but he was from Africa. The Falcon, however, was the first black American superhero."

^ Wright, p. 239

^ Saffel, Steve (2007). "Bucking the Establishment, Marvel Style". Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon. Titan Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4.The stories received widespread mainstream publicity, and Marvel was hailed for sticking to its guns.

^ Daniels, pp. 152 and 154: "As a result of Marvel's successful stand, the Comics Code had begun to look just a little foolish. Some of its more ridiculous restrictions were abandoned because of Lee's decision."

^ van Gelder, Lawrence (February 4, 1971). "A Comics Magazine Defies Code Ban on Drug Stories; Comics Magazine Defies Industry Code". The New York Times. p. 37.

^ "Comic Geek Speak: Episode 83". 2005-12-12. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

^ "2008 National Medal of Arts – Stan Lee". National Endowment for the Arts. November 17, 2008. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010. Biography linked to NEA press release "White House Announces 2008 National Medal of Arts Recipients", Archived August 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. August 26, 2009.

^ Comtois, Pierre; Montejo, Gregorio (July 16, 2007). "Silver Age Marvel Comics Cover Index Reviews". Samcci.Comics.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 61: "Stan Lee had returned to The Amazing Spider-Man for a handful of issues after leaving following issue #100 (September 1971). With issue #110. Lee once again departed the title into which he had infused so much of his own personality over his near 10-year stint as regular writer."

^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 157

^ Saffel, "An Adventure Each Day", p. 116: "On Monday January 3, 1977, The Amazing Spider-Man comic strip made its debut in newspapers nationwide, reuniting writer Stan Lee and artist John Romita."

^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 187: "[In 1978], Simon & Schuster's Fireside Books published a paperback book titled The Silver Surfer by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby...This book was later recognized as Marvel's first true graphic novel."

^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 197: "With the help of artist John Buscema, [Stan] Lee created Jennifer Walters, the cousin of Bruce Banner."

^ ab Stan Lee at the Grand Comics Database

^ Catron, Michael (August 1981). "Silver Surfer Special Set". Amazing Heroes. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books (3): 17.

^ Lee, Stan; Buscema, John (1988). Silver Surfer: Judgement Day. Marvel Comics. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-87135-427-3.

^ Lofficier, Jean-Marc (December 1988). "Moebius". Comics Interview (64). Fictioneer Books. pp. 24–37.

^ Lee, Stan; Pollard, Keith (1990). Silver Surfer: The Enslavers. Marvel Comics. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-87135-617-8.

^ Lee, Mair[page needed]

^ Dean, Michael (August 2005). "How Michael Jackson Almost Bought Marvel and Other Strange Tales from the Stan Lee/Peter Paul Partnership" (270). (excerpt) The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008.

^ SEC Litigation Release No. LR-18828, August 11, 2004.

^ "Stan Lee Media CEO Kenneth Williams Accused of Shareholder Fraud and Libel in Court Filing By Former Stan Lee Media Executive: Accusations Against Peter Paul Retracted and Corrected in Court Filing". Freund & Brackey LLP press release. May 7, 2001. Archived from the original on August 1, 2011.

^ United States Attorney's Office (March 8, 2005). "Peter Paul, Co-founder of Stan Lee Media, Inc., Pleads Guilty to Securities Fraud Fraud Scheme Caused $25 Million in Losses to Investors and Financial Institutions". press release. Archived from the original on March 11, 2005. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

^ Witt, April (October 9, 2005). "House of Cards". The Washington Post. p. W10. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011.

^ "Ringo Starr to become superhero". BBC News. August 6, 2004. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013.

^ Lee in Lovece, Frank (April 1, 2007). "Fast Chat: Stan Lee". Newsday. Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

^ "Stan Lee Launches New Online Comic Venture". CBC. August 6, 2004. Archived from the original on August 10, 2004.

^ "Marvel Sued for $5 Billion". Library Journal. March 21, 2007. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

^ "June 9: Stan Lee Media, Inc. Files Expected Lawsuit Against Stan Lee". TheComicsReporter.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

^ Stan Lee Media, Inc. v. Stan Lee, QED Productions, Inc., and POW! Entertainment, Inc., CV 07 4438 SJO (C.D. Cal. July 9, 2007).

^ Lee, Stan (2008). Election Daze: What Are They Really Saying?. Filsinger Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-9702631-5-5.

^ "Stan Lee Launching Legion of 5". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

^ Boucher, Geoff (April 19, 2008). "Stan Lee to oversee Virgin Comics' superheroes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008.

^ "Stan Lee 'to create world's first gay superhero'". The Daily Telegraph. January 14, 2009. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014.

^ "Skyscraperman". skyscraperman.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014.

^ "NHL, Spider-Man creator Stan Lee join on new superheroes project". National Hockey League. October 7, 2010.

^ Langshaw, Mark (August 2, 2010). "Stan Lee backs Eagle Initiative". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

^ Kepler, Adam W. (October 16, 2011). "Monsters v. Kittens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

^ Moore, Matt (October 14, 2011). "Stan Lee's got a new universe, and it's for kids". Associated Press/MSNBC. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

^ Greenberger, Robert (July 11, 2012). "Enter Stan Lee's World of Heroes". ComicMix. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013.

^ Sacks, Jason (n.d.). "Peter David and Jace Hall Join the World of Heroes". Comics Bulletin. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

^ Van, Alan (July 12, 2012). "SDCC: 'Stan Lee's World of Heroes' YouTube Channel". NMR. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014.

^ Seifert, Mark (July 13, 2012). "The Stan Channel: Stan Lee, Peter David, Mark Hamill, Adrianne Curry, America Young, And Bonnie Burton On Stan Lee's World Of Heroes". BleedingCool.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013.

^ "Disney Publishing Worldwide Announces New Zodiac-Based Book with Comics Legend Stan Lee" (Press release). November 2, 2013. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013.

^ Frater, Patrick (February 27, 2013). "Josephson joins Annihilator". Film Business Asia. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

^ Mitchell, Aric (February 21, 2013). "Stan Lee's Annihilator: Chinese Superhero Coming To Big Screen". The Inquisitr. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

^ Konow, David (February 25, 2013). "Stan Lee is back with Annihilator". TG Daily. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

^ Cowsill, Alan; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "2000s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.It was quite a coup. Stan "The Man" Lee...swapped sides to write for DC. Teaming up with comicdom's top artists, Lee put his own unique take on DC's iconic heroes.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ "NYCC 08: Stan Lee Dives into Manga". IGN. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

^ "Stan Lee, Bones Confirmed to be Working on Hero Man". Anime News Network. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

^ "Stan Lee & Bones' Heroman Anime Now in Production". Anime News Network. October 6, 2009. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

^ Hetrick, Adam (January 4, 2011). "Stan Lee Encouraged by Spider-Man; New Projects on the Horizon". Playbill. Archived from the original on August 1, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

^ ab Richards, Dave (August 24, 2006). "The Man Comes Around: Lee talks Stan Lee Meets". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Archive requires scrolldown

^ "Stan Lee: Marvel Legends". OAFE.net. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Duke, Alan (April 11, 2012). "Stan Lee launches his own comic convention". CNN. Archived from the original on August 15, 2012.

^ Wiebe, Sheldon (July 18, 2016). "Comic-Con 2016: POW! Entertainment and Shatner Singularity Introduce Stan Lee's God Woke!" (Press release). Shatner Singularity. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016 – via EclipseMagazine.com. Additional on December 22, 2016. (WebCitation page requires text-blocking to make text visible)

^ LeBlanc, Sarah (July 22, 2016). "Stan Lee puts philosophical spin on comic book adventure". Philadelphia Daily News. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ Niu, Mark (July 24, 2016). "Comic book legend Stan Lee treated like royalty at Comic-Con". China Central Television. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

^ McLaughlin, Jeff (2007). Stan Lee: Conversations. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. Chronology xvii. ISBN 978-1578069859.

^ "2017 Independent Publisher Book Awards". Independent Publisher Book Awards. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

^ "Stan Lee Foundation official site". Retrieved May 15, 2017.

^ "Inventory of the Stan Lee Papers, 1942–2001". University of Wyoming. 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

^ Christiansen, Jeff (February 15, 2014). "Stan Lee (as a character)". The Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

^ Jensen, K. Thor. "Jack Kirby's Greatest WTF Creations". UGO.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

^ Brick, Scott (March 2007). "Alex Ross". Wizard Xtra!. p. 92.

^ Morales, Robert (w), Baker, Kyle (p), Baker, Kyle (i). "The Blackvine" Truth: Red, White & Black 7 (July 2003)

^ Lott, Rod (July 18, 2006). "Q&A with The Chinatown Death Cloud Peril's Paul Malmont". Bookgasm.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012.

^ Kelly, Stuart (October 25, 2013). "The Violent Century by Lavie Tidhar – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

^ Chris Hewitt; Al Plumb. "Stan Lee's Marvellous Cameos – Now With Even More Cameos". Empireonline.com. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

^ "Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017) - From 'X-Men' to 'Spider-Man': 35 of Stan Lee's Most Memorable Cameos". Hollywoodreporter.com. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

^ Lee in "Is there a God?". The A.V. Club. October 9, 2002. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

^ Lewine. "Image 2". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ "Stan & Joan Lee's Love Story". Daily Entertainment News. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

^ Lee, Mair, p. 69

^ Lewine. "Images 4–5". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Lee, Mair, p. 74

^ Lewine. "Images 6–7". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Lewine. "Image 10". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Lewine. "Image 8". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Lewine. "Image 11". Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ "Comic Book Legend Stan Lee Gets a Pacemaker". City News Service. September 28, 2012. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013 – via Beverly Hills Courier....the procedure performed last week.

^ "Pow! Entertainment Releases a Message from Its Chairman Stan Lee" (Press release). POW! Entertainment. September 28, 2012. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

^ Lewis, Andy (July 6, 2017). "Joan Lee, Wife of Marvel Comics Legend Stan Lee, Dies at 95". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

^ "Inkpot Award". San Diego Comic-Con. 2016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017.

^ "Will Eisner Hall of Fame". The Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards. 2014. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014.

^ Curry, Stormy (October 31, 2013). "Stan Lee: It's All In The Cameos With Marvel Movies". KTTV. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014.

^ Garreau, Joel (November 18, 2008). "Stan Lee and Olivia de Havilland Among National Medal of Arts Winners". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

^ "TV: Video Highlights from the 2009 Spike TV Scream Awards". Bloody-disgusting.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ Simpson, David (January 4, 2011). "Video: Stan Lee Picks Up 2,428th Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

^ "Stan Lee to Receive 2012 Producers Guild Vanguard Award". The Hollywood Reporter. November 9, 2011. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

^ "2016 Awards". National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017.

^ ab Meeks, Robert (October 2, 2009). "L.B. Comic Con: It's Stan Lee Day!". Insidesocal.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

^ McMillan, Graeme (July 16, 2017). "Jack Kirby to Be Named 'Disney Legend' at D23 Expo in July". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

^ News, A. B. C. (July 19, 2017). "Stan Lee imprints his hands and feet in concrete at TCL Chinese Theatre". ABC News. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018.

^ Cassell, Dewey (October 2010). "One Day at a Time: The Amazing Spider-Man Newspaper Strips". Back Issue!. TwoMorrows Publishing (44): 63–67.Lee has penned The Amazing Spider-Man newspaper strip since the beginning.

Further reading

McLaughlin, Jeff, ed. (2007). Stan Lee: Conversations. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-985-9.

Ro, Ronin (2005) [first published 2004]. Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, and the American Comic Book Revolution. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-58234-566-6.

Jordan, Raphael; Spurgeon, Tom (2003). Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-506-3.

External links

- Official website

Stan Lee at Curlie

Stan Lee at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

Stan Lee at the Comic Book DB

Stan Lee at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Stan Lee on IMDb

Stan Lee at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

Stan Lee at Web of Stories

| Business positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Joe Simon | Marvel Comics Editor-in-Chief 1941–1942 | Succeeded by Vincent Fago |

| Preceded by Vincent Fago | Marvel Comics Editor-in-Chief 1945–1972 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |

| Preceded by n/a | Fantastic Four writer 1961–1971 | Succeeded by Archie Goodwin |

| Preceded by Archie Goodwin | Fantastic Four writer 1972 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |

| Preceded by n/a | The Amazing Spider-Man writer 1962–1971 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |

| Preceded by Roy Thomas | The Amazing Spider-Man writer 1972–1973 | Succeeded by Gerry Conway |

| Preceded by n/a | The Incredible Hulk writer (including Tales to Astonish stories) 1962–1968 | Succeeded by Gary Friedrich |

| Preceded by Gary Friedrich | The Incredible Hulk writer 1968–1969 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |

| Preceded by n/a | Thor writer (including Journey into Mystery stories) 1962–1971 (with Larry Lieber in 1962) (with Robert Bernstein in 1963) | Succeeded by Gerry Conway |

| Preceded by n/a | The Avengers writer 1963–1966 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |

| Preceded by n/a | (Uncanny) X-Men writer 1963–1966 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |

| Preceded by n/a | Captain America writer (including Tales of Suspense stories) 1964–1971 | Succeeded by Gary Friedrich |

| Preceded by n/a | Daredevil writer 1964–1969 | Succeeded by Roy Thomas |