Grand Duchy of Finland

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (April 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Finnish. (January 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Grand Duchy of Finland Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta (Finnish) Storfurstendömet Finland (Swedish) Великое княжество Финляндское (Russian) Velikoye knyazhestvo Finlyandskoye | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1809–1917 | |||||||||||||

Flag  Coat of arms | |||||||||||||

Anthem: Maamme / Vårt land[citation needed] "Our Land" | |||||||||||||

The Grand Duchy of Finland in 1914. | |||||||||||||

| Status | Governorate-General of the Russian Empire | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Turku (1809–1812) Helsinki (1812–1917) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Swedish, Finnish, Russian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Lutheran, Finnish Orthodox | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Grand Duke | |||||||||||||

• 1809–1825 | Alexander I | ||||||||||||

• 1825–1855 | Nicholas I | ||||||||||||

• 1855–1881 | Alexander II | ||||||||||||

• 1881–1894 | Alexander III | ||||||||||||

• 1894–1917 | Nicholas II | ||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||

• 1809 | Georg Sprengtporten (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1917 | Nikolai Nekrasov (last) | ||||||||||||

| Vice Chairman | |||||||||||||

• 1822–1826 | Carl Erik Mannerheim (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1917 | Anders Wirenius (last) | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Diet of Porvoo | 29 March 1809 | ||||||||||||

• Treaty of Fredrikshamn | 17 September 1809 | ||||||||||||

• Independence declared | 6 December 1917 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1910 | 360,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1910 | 2943000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Swedish riksdaler (1809–1840) Russian ruble (1840–1865) Finnish markka (1865–1917) | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | FI | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

The Grand Duchy of Finland (Finnish: Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta, Swedish: Storfurstendömet Finland, Russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Finlyandskoye; literally Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecessor state of modern Finland. It existed between 1809 and 1917 as an autonomous part of the Russian Empire and was ruled by the Russian Emperor as Grand Duke.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Formation of the Grand Duchy

1.2 Early years

1.3 Alexander's death and the assimilation of Finland: 1820s–1850s

1.4 The Crimean War and the 1860s–1870s

1.5 Russification

2 Politics

3 Geography

4 Provinces

5 Historical population of the Grand Duchy

6 Flags and heraldry

7 See also

8 References

9 Bibliography

10 Further reading

11 External links

History

An extended Southwest Finland was made a titular grand duchy in 1581, when King John III of Sweden, who as a prince had been the Duke of Finland (1556–1561/63), extended the list of subsidiary titles of the Kings of Sweden considerably. The new title Grand Duke of Finland did not result in any Finnish autonomy, as Finland was an integrated part of the Kingdom of Sweden with full parliamentary representation for its counties. During the next two centuries, the title was used by some of John's successors on the throne, but not all. Usually it was just a subsidiary title of the king, used only on very formal occasions. However, in 1802, as an indication of his resolve to keep Finland within Sweden in the face of increased Russian pressure, King Gustav IV Adolf gave the title to his new-born son, Prince Carl Gustaf, who died three years later.

During the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, the four Estates of occupied Finland were assembled at the Diet of Porvoo on 29 March 1809 to pledge allegiance to Alexander I of Russia, who in return guaranteed that the area's laws and liberties as well as religion would be left unchanged. Following the Swedish defeat in the war and the signing of the Treaty of Fredrikshamn on 17 September 1809, Finland became a true autonomous grand duchy within the autocratic Russian Empire; but the usual balance of power between monarch and diet resting on taxation was not in place, since the Emperor could rely on the rest of his vast Empire. The title "Grand Duke of Finland" was added to the long list of titles of the Russian Tsar.

After his return to Finland in 1812, the Finnish-born Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt became counsellor to the Russian emperor. Armfelt was instrumental in securing the Grand Duchy as an entity with relatively greater autonomy within the Russian realm, and restoring the so-called Old Finland that had been lost to Russia in the Treaty of Nystad in 1721.[1]

Formation of the Grand Duchy

The formation of the Grand Duchy stems from the Treaty of Tilsit between Tsar Alexander I of Russia and Napoleon Bonaparte of France. The treaty mediated peace between Russia and France and allied the two countries against Napoleon's remaining threats: Great Britain and Sweden. Russia invaded Finland in February 1808, claimed as an effort to impose military sanctions against Sweden, but not a war of conquest, and that Russia decided to only temporarily control Finland. Collectively, the Finnish were predominately Anti-Russian, and Finnish guerillas and peasant uprisings were a large obstacles for the Russians, forcing Russia to use various tactics to quash armed Finnish rebellion. Thus, in the beginning of the war, General Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden, with permission of the Tsar, issued an oath of fealty on Finland, in which Russia would honor Finland's Lutheran faith, the Finnish Diet, and the Finnish estates as long as the Finns would remain loyal to the Russian crown. The oath also dubbed anyone person who gave aid to the Swedish or Finnish armies a rebel.[2]

The Finns complied, bitter over Sweden abandoning the country for their war against Denmark and France, and begrudgingly embraced Russian conquest. The Diet of Finland was now to only meet whenever requested, and was never mentioned in the manifesto published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Further on, Alexander I requested a deputation of the four Finnish estates, as he expressed concern over continued Finnish resistance. The deputation refused to act without the Diet, to which Alexander agreed with, and promised the Diet would shortly be summoned. By 1809, all of Finland had been conquered and The Diet was summoned in March. Finland was then united through Russia via crown, and Finland was able to keep the majority of its own laws, giving it autonomy.[3][4]

Early years

The earlier years of the Grand Duchy can be seen as uneventful. In 1812, the area of Old Finland, known as the Viipuri Province was returned to Finland after being annexed by Russia in the Great Northern War and the Russo-Swedish War (1741–1743). This surprising action by the Tsar was met with anger from certain parts of the Russian government and aristocracy, who wished to either return to the previous border or annex the communities west of St. Petersburg. Despite the outcry, the borders remained set until 1940. The gesture can be seen as Alexander's concern for Finland and his attempts of appeasement of the Finns, in attempts to gain their loyalty which would come from passive appeasement, compared to the vigorous Russification later in the 1800s. Moreover, Alexander moved the capital from Turku to Helsinki, a small fortified town protected by Suomenlinna. Finland's main university also transferred to Helsinki after a fire broke out in Turku, destroying most of the building.

Despite promises of a Finnish Diet, the Diet was not called to meet until 1863 and many new laws going through the legislature would have required the approval of the Diet while under Sweden. Alexander went a step further to demand a Finnish House of Nobles, which organized in 1818. The house was designed to register all noble families in Finland, so that the highest Finnish estate would be representative of the next Finnish Diet. As for Sweden, the majority did not think too much about Finland's conquest, as Sweden itself annexed Norway from Denmark in 1814 and entered a personal union with the nation. Whether or not Alexander purposely ignored the existence of the Diet is debatable, with notable factors such as the fall of Napoleon and the creation of the Holy Alliance, newfound religious mysticism of the Russian crown, and the negative experience with the Polish sejm. Despite this, Alexander I ceased to give in to Finnish affairs and returned to governing Russia.[5]

Alexander's death and the assimilation of Finland: 1820s–1850s

In 1823, Arseny Zakrevsky was made governor general of Finland and quickly became unpopular by the Finns and Swedes alike. Zakrevsky abolished the Committee for Finnish Affairs and managed to obtain the right to submit Finnish affairs to the Tsar, bypassing the Finnish Secretary of State. Two years later, Alexander died. Zakrevsky used this opportunity to push an oath of fealty on Finland, which would refer to the Tsar the absolute ruler of Finland, which was planned to be Constantine, Alexander's younger brother. However, Nicholas, younger brother of Constantine and Alexander, became Tsar despite the Decembrist revolt against him. Nicholas assured Finland's secretary of state, Robert Henrik Rehbinder, that Nicholas would continue to uphold Alexander's liberal policies regarding Finland. By 1830, Europe had become a hotbed of revolution and reform as a result of the July Revolution in France. Poland, another Russian client state, hosted a massive uprising against the Tsar during the November Uprising. Finland made no such move, as Russia had already won over Finnish loyalty some decades ago. Thus, Russia continued its policies respecting Finnish autonomy and the quiet assimilation of the Finns into the empire. Zakrevsky died in 1831 and was replaced with Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov, who continued Finnish appeasement. The appeasement of the Finns could be seen as a prototype to the later Russification, as educated Finns moved to Russia in mass, seeking jobs within the Tsarist court to rise within Russian imperialist society. The Russian language was studied excitedly as well, with more Finns seeking to learn Russian language, politics, culture, and assimilate into Russian society. Even though, Nicholas had no intentions on doing this, his inner office, specifically Nicholas's Interior Minister, Lev Perovski, advocated for Arseny Zakrevsky's ideas and further pushed the ideas of subtle Russification during the 1840s.[6]

However, Finland had a nationalistic revolution in the 1830s based around literature. It marked the beginning of the Fennoman movement, a nationalistic movement that would continue until Finnish independence. In 1831, the Finnish Literary Society was founded, also on the basis of appreciation of the Finnish language. Finnish was not a language of the scholarly elite, as most printed academic work, novels, and poetry were written in either Swedish or Russian. Copying the German reading rage, Lesewut, and subsequent Swedish mania, reading became increasingly popular in Finland during the 1830s. This rage heightened in 1835 with the publication of Kalevala, the Finnish epic. Kalevala's influence on Finland was massive, and strengthened Finnish nationalism and unity, despite the epic being poetry or stories about Finnish folklore. The quest for literature expanded into the 1840s and 1850s, and caught the eye of the Finnish church and the Russian crown. Finnish newspapers, such as Maamiehen Ystävä (The Farmer's Friend), began being published in both urban and rural areas of Finland. Despite this, Finland's literature movement was met with opposition from the Swedish academic elite, the church, and the Russian government. Archbishop Edvard Bergenheim called for a double censorship on works that go against the church and works that are socialist or communist. The reactionary policies of the Lutheran Church convinced the also reactionary Nicholas I to prohibit the publishing of all Finnish works that were not religious or economical, as such works would have been considered revolutionary and would convince the Finnish majority to revolt against the church and crown. Despite that, the censorship only fueled Finland's language strife and the Fennomanian movement.[7][8][9]

The Crimean War and the 1860s–1870s

The works of Johan Snellman and other Finnoman authors combined literature and nationalism and increased the calls for language recognition and education reforms in Finland. This heightened during the Crimean War in which Finnish ports and fortresses on the Baltic Sea became subject for Allied attacks, specifically Suomenlinna and Bomarsund in the Åland Islands. As newspapers were printed in Swedish and Russian due to the censorship, many Finns could not read about the events of the Battle of Bomarsund and the Battle of Suomenlinna. Moreover, Nicholas I died in 1855, and the new emperor, Alexander II, had already planned educational reforms in outlying territories in Russia, including Finland.[10] Alexander II also planned to call on the Diet of the Estates once more. Under Alexander's rule, Finland experiences a period of liberalization in education, the arts, and economic desires. In 1858, Finnish was made the official language of local self-governments, such as provinces, where Finnish was the majority of the language spoken. However, the Finns feared that Moscow would prevent the Diet from meeting on the basis that Polish and Russian citizens did not receive the same liberties, and that the Diet would be eradicated. It was misinterpreted, as it only added a few extra steps to how the lawmaking process worked; the Diet was allowed to stay.

In 1863, Alexander called the Diet and issued that the Finnish language was to be on par with Swedish and Russian in the Grand Duchy, while also passing laws regarding infrastructure and currency. Alexander came to favor the Finnish working class over the Swedish elite, due to Swedish propaganda during the Crimean War urging revolt against the Russians. Alexander also passed a law regarding language ordinance in August 1863, requiring that the Finnish language must be introduced to all public institutions within twenty years. The law was expanded in 1865 to require that state offices must serve the public in Finnish if requested. Despite this, the language laws took time to be fully implemented due to the interference of the Swedish elite, who owned most of these offices and businesses. Despite this, the education laws pushed through and the first secondary schools instructed in Finnish began in the 1870s. [11][12] The power of the Diet was also expanded in 1869, as it allowed the Diet more power and the ability to initiate various legislation; the act also called the Tsar to call upon the Diet every five years. An act passed regarding religion was also passed in 1869 which prevented the power of the State over the church. Moreover, Finland also received its own monetary system, the Finnish markka, and its own army.[13]

Russification

The policies of Russification under Alexander III and Nicholas II easily sum up the time period from 1881 to 1917. In 1881, Alexander III took the throne after the death of his father, and began a rule of staunch conservative, yet peaceful, rule of Russia. Finland, as well as many other outlying Russian territories, faced the burden of Russification, the cultural, social, economical, and political absorption into Russia. Compared to the early Russification of the 1830s and 1840s, the Russification of the late 19th-early 20th century was much more vigorous in its policies. Moreover, Finland faced political turmoil within its nation between various factions such as liberals, Social Democrats, Young Finns, and communists. Finland became a target for the Pan-Slavist movement, which called for Slavic unity in eastern Europe. Finland was viewed as conquered territory, and that as subjects, Finland was to respect the Tsar. Finland was also viewed as a land of settlement and that the "alien race" of the Finns were to be assimilated and protected from Western interference, thereby "blessing" the Finns with their presence. Moreover, Finnish representatives to the Tsar were replaced with Pan-Slavist advocates.[14]

Russification only increased from there, but from the 1880s on, the conflict between the Swedish minority halted. Compared to the Baltic States, the Finnish majority was far better educated and more keen in Russian politics. The reactionary policies of Russification, which aimed to combine secular nationalism and a divine right monarchy, infiltrated the Finnish economy in 1885. Finland had managed to create a thriving modern industry based around textiles and timber that managed to rival the Russian economy at the time. Russian bureaucrats, out of both shock and jealousy, called for the revision of the Russo-Finnish Tariff. Russification had taken an economic turn as well, as the basis of the reformed tariff was economic uniformity, which only furthered economic difficulties of Finland. The tariff's revision in 1885, and subsequently 1897, was formed out of spite of Finland's commercial success and working class unity. Russification policies continued into 1890, with the addition of the Imperial Post System in Finland, replacing the Finnish post. It was not until the mid-1890s, that the Finnish people realized the true intentions of the Russian crown.

Nicholas II ascended to the throne in 1894 after Alexander's death, and with him came General Nikolay Bobrikov, who was appointed governor-general. Under Bobrikov, the Finns had a near collective hatred of him, whose reactionary policies gave rise to socialism and communism among the Finnish working class. The Party of Active Resistance and Kagal, in particular, became very popular in Finland for the former's tactics of violence and the latter's tactic of propaganda and persuasion. At the beginning of this reign, Bobrikov almost immediately introduced a mandatory five-year military service, in which Finns had the possibility of being drafted into Russian units. Furthermore, he instituted that Russians be given the opportunity to serve in public office and that Russian be made the administrative language of Finland. In 1899, the February Manifesto under Nicholas II declared that Russian law was the law of the land, and Finland was to pledge allegiance to Russian law. The Diet was essentially downgraded to a state assembly and that Finland was a province of Russia, ignoring its autonomy. The Finnish Army as a whole was dissolved in 1901.[15][16]

Bobrikov unintentionally united both Finns and Swedes against Russia, which only angered him more. With churches refusing to proclaim the law, judges refusing to carry it out, and conscripts refusing service, Bobrikov went on a frenzy with the current state of Finland. Bobrikov found little support in Finland, mainly from the Russian minority and members of the Old Finnish Party, an extreme right-wing party that found little success. Bobrikov brought in Russian officials to take government and state spots and, in an extreme act of anger, suspended the Finnish Constitution in 1903. His actions were met with extreme anger from Finns and Swedes, in which the moderate parties, the Young Finns and the Swedish Party combined to collectively fight Bobrikov. The Social Democratic Party of Finland, a Marxist party popular among peasants was also extremely hostile and advocated class warfare and took arms, in contrast to the Social Democrats elsewhere in Europe. Finally, the Party of Active Resistance, a far-left party that advocated an armed struggle and guerilla tactics, received fame when member Eugen Schauman assassinated Bobrikov in Helsinki on June 16, 1904.[16]

In 1905, Russia faced a humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and amidst the turmoil in St. Petersburg, Finns remade their constitution and formed a new Diet whose representation was based on universal suffrage, giving women full suffrage before any other European nation after the short lived Republic of Corsica. However, the Diet was quickly destroyed by Pyotr Stolypin, Nicholas II's prime minister. Stolypin proved to be even more vigorous than Bobrikov, as he believed every subject should be a stoic patriot to the crown and uphold undying loyalty to Russia. Stolypin wished to destroy Finland's autonomy and disregarded native tongues and cultures of non-Russian subjects, believing them to be traditional and ritualistic at best. The Finnish Diet once again formed to combat Stolypin, but Stolypin was bent on quashing Finnish insurrection and permanently disbanded the Diet in 1909. As with Bobrikov before him, Stolypin was unaware that such actions only fanned the flames and was subsequently assassinated by Dmitry Bogrov, a Ukrainian member of the far-left. From Stolypin's death henceforward, the Russian crown ruled Finland as a monarchist dictatorship until Russia's collapse during the Russian Revolution, from which Finland declared independence, a war of independence that soon transformed into a civil war.[17][18][19]

Politics

The constitutional status of Finland was not codified in Russian law until the February Manifesto of 1899, by which time Finns and Russians had developed quite different ideas about the status of Finland. The autonomy of Finland was at first encouraged by the Russians, in part due to the relatively developed governmental structures in Finland (as compared to the emperor-centered Russia of early 19th century) and in part as a deliberate policy of goodwill to win over the minds of the Finnish people. This autonomous status led the Finns to develop their own ideas of nationalism and constitutional monarchy, which they could to a large extent implement in practice with the assent of the Tsar. However, while each tsar agreed at the time of his coronation to uphold the special status of the local laws in Finland, there is no evidence that they regarded themselves as bounded by any actual constitutional laws, despite the growing prevalence of such an interpretation in Finland in the late 19th century. As governmental organizations developed in Russia, and unity of the empire became one of the leading tenets of Russian politics, clashes between the Russian and Finnish governmental organizations grew frequent and led to the attempted russification.

Finland nevertheless enjoyed a high degree of autonomy until its independence in 1917. In 1917, after the February Revolution in Russia, Finland's government worked towards securing and perhaps even increasing Finland's autonomy in domestic matters. On 6 December 1917, shortly after the October Revolution in Russia, Finland declared its independence.

After the Finnish Civil War, which led to a temporary majority of monarchists in the parliament, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse was elected as the new monarch, but as king instead of grand duke, marking the new status of the nation; but he never reigned, as a republic was proclaimed after Germany's defeat in the First World War.

The Russian emperor ruled as the Grand Duke of Finland and was represented in Finland by the Governor-General of Finland. The Senate of Finland was the highest governing body of the Grand Principality, and was composed of native Finns. In St. Petersburg Finnish matters were represented by the Minister–Secretary of State for Finland. From 1863 onwards the Diet of Finland met regularly. In 1906, the Diet, with its hereditary rather than universally elected representation, was dissolved and the modern Parliament of Finland was established. Finland was one of the first regions in the world to implement universal suffrage and eligibility, including for women and for landless people.

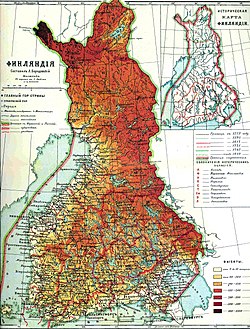

The Provinces of Finland, about 1900. The map is in Russian and uses the Swedish place names with Cyrillic transcriptions.

Geography

The Grand Duchy of Finland lay approximately within the same borders that had existed before the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940. The main difference was Petsamo, which was ceded to Finland in the Treaty of Tartu in 1920.

Provinces

The administrative division of the Grand Duchy followed the Russian imperial model with provinces (Russian: губерния governorate, Swedish: län, Finnish: lääni) headed by governors. However few changes were made and as the language of the administrators was still Swedish the old terminology from during the Swedish time continued in local use. The Viipuri Province was not initially part of the Grand Duchy, but in 1812 it was transferred by Tsar Alexander I from Russia proper to Finland. After 1831 there were eight provinces in the Grand Duchy until the end and that continued in the independent Finland:

Turku and Pori Province (Russian: Або-Бьернеборгская губерния, Swedish: Åbo och Björneborgs län, Finnish: Turun ja Porin lääni)

Kuopio Province (Russian: Куопиоская губерния, Swedish: Kuopio län, Finnish: Kuopion lääni)

Vaasa Province (Russian: Николайстадская губерния, Swedish: Vasa län, Finnish: Vaasan lääni)

Uusimaa Province (Russian: Нюландская губерния, Swedish: Nylands län, Finnish: Uudenmaan lääni)

Mikkeli Province (Russian: Санкт-Михельская губерния, Swedish: St. Michels län, Finnish: Mikkelin lääni)

Häme Province (Russian: Тавастгусская губерния, Swedish: Tavastehus län, Finnish: Hämeen lääni)

Oulu Province (Russian: Улеаборгская губерния, Swedish: Uleåborgs län, Finnish: Oulun lääni)

Viipuri Province (Russian: Выборгская губерния, Swedish: Viborgs län, Finnish: Viipurin lääni)

Historical population of the Grand Duchy

- 1810: 863,000[20]

- 1830: 1,372,000

- 1850: 1,637,000

- 1870: 1,769,000

- 1890: 2,380,000

- 1910: 2,943,000

- 1920: 3,148,000

Flags and heraldry

The arms were originally designed for the sarcophagus of Gustav I Vasa around 1580, depicting a gold heraldic lion on a red shield holding a raised sword in its right hand and trampling a curved sabre.

In the 1860s, talks about a Finnish flag started in the fennoman movement. In 1863 numerous proposals were presented for a national flag.[21] The two main proposals were flags based on red/yellow and blue/white. The flag proposals never had a chance to be presented to the Diet, so none of them ever became an official flag. However people used different designs with these colors for flags of their own choosing. Since 1821, merchant ships were permitted to fly the Russian flag (horizontal white-blue-red tricolor) without a special permit.

See also

- Military of the Grand Duchy of Finland

- Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic

Congress Poland – Kingdom of Poland (1815–1831), another constitutional monarchy within the Russian Empire- Grand Duchy of Lithuania

References

^ Knapas, Rainer (2014). "Ajankohtainen Armfelt". Tieteessä tapahtuu (in Finnish). Retrieved 2016-04-30.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 178–79, 183.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, p. 185.

^ Seton-Watson 1967, pp. 114–15.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 191–92, 194.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 195–96.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 199–206.

^ Hall 1953, pp. 127–28.

^ Mäkinen 2015, pp. 292–95.

^ Mäkinen 2015, pp. 295–96.

^ Hall 1953, p. 128.

^ Seton-Watson 1967, pp. 415–16.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 215–16, 222.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 222–24.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 229–32.

^ ab Seton-Watson 1967, pp. 498–99.

^ Seton-Watson 1967, pp. 668–69.

^ Jutikkala & Pirinen 1962, pp. 242–55.

^ Hall 1953, p. 129.

^ B. R. Mitchell, European Historical Statistics, 1750–1970 (Columbia U.P., 1978), p. 4

^ Finland flag proposals: newspapers - Flags of the world

Bibliography

Hall, Wendy (1953), Green, Gold, and Granite, London: Max Parrish & Co. .

Jutikkala, Eino; Pirinen, Kauko (1962), A History of Finland (rev. ed.), New York, Washington: Praeger Publishers .

Mäkinen, Ilkka. (Winter 2015), "From Literacy to Love of Reading: The Fennomanian Ideology of Reading in the 19th-Century Finland", Journal of Social History, 49 (2) .

Seton-Watson, Hugh (1967), The Russian Empire 1801–1917, London: Oxford .

Further reading

- Alenius, Kari. "Russification in Estonia and Finland Before 1917," Faravid, 2004, Vol. 28, pp. 181–94 Online

- Huxley, Steven. Constitutionalist insurgency in Finland: Finnish "passive resistance" against Russification as a case of nonmilitary struggle in the European resistance tradition (1990)

- Jussila, Osmo, et al. From Grand Duchy to a Modern State: A Political History of Finland Since 1809 (Hurst & Co. 1999).

- Kan, Aleksander. "Storfurstendömet Finland 1809–1917 – dess autonomi enligt den nutida finska historieskrivningen" (in Swedish) ["Autonomous Finland 1809–1917 in contemporary Finnish historiography"] Historisk Tidskrift, 2008, Issue 1, pp. 3–27

- Polvinen, Tuomo. Imperial Borderland: Bobrikov and the Attempted Russification of Finland, 1898–1904 (1995) Duke University Press. 342 pp.

- Thaden, Edward C. Russification in the Baltic Provinces and Finland (1981). JSTOR

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Duchy of Finland. |

Grand Duchy of Finland at Flags of the World- The text of The Imperial Manifesto of 1811 in German and Finnish

"Finland, Grand Duchy of". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Finland, Grand Duchy of". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.