Urethra

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| Urethra | |

|---|---|

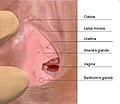

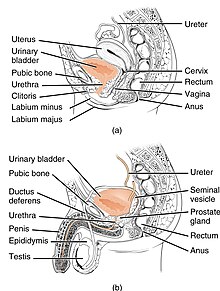

The urethra transports urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. This image shows (a) a female urethra and (b) a male urethra. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus |

| Artery | Inferior vesical artery Middle rectal artery Internal pudendal artery |

| Vein | Inferior vesical vein Middle rectal vein Internal pudendal vein |

| Nerve | Pudendal nerve Pelvic splanchnic nerves Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | Internal iliac lymph nodes Deep inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | urethra vagina; feminina (female); urethra masculina (male) |

| Greek | οὐρήθρα |

| MeSH | D014521 |

| TA | A08.4.01.001F A08.5.01.001M |

| FMA | 19667 |

Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

In anatomy, the urethra (from Greek οὐρήθρα – ourḗthrā) is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the urinary meatus for the removal of urine from the body. In males, the urethra travels through the penis and also carries semen.[1] In human females and other primates, the urethra connects to the urinary meatus above the vagina, whereas in non-primates, the female's urethra empties into the urogenital sinus.[citation needed]

Females use their urethra only for urinating, but males use their urethra for both urination and ejaculation.[1] The external urethral sphincter is a striated muscle that allows voluntary control over urination.[2] The internal sphincter, formed by the involuntary smooth muscles lining the bladder neck and urethra, is innervated by the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system.[3] The internal sphincter is present both in males and females.[4][5][6]

Contents

1 Anatomy

1.1 Male

1.2 Female

1.3 Histology

2 Development

3 Physiology

3.1 Sexual physiology

4 Clinical significance

4.1 Investigations

4.2 Catheterization

5 Additional images

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Anatomy

Male

In the human male, the urethra is about 8 inches (20 cm) long and opens at the end of the external urethral meatus.[7] The urethra provides an exit for urine as well as semen during ejaculation.[1]

The urethra is divided into four parts in men, named after the location:

| Region | Description | Epithelium |

| pre-prostatic urethra | This is the intramural part of the urethra and varies between 0.5 and 1.5 cm in length depending on the fullness of the bladder. | Transitional |

| prostatic urethra | Crosses through the prostate gland. There are several openings: (1) the ejaculatory duct receives sperm from the vas deferens and ejaculate fluid from the seminal vesicle, (2) several prostatic ducts where fluid from the prostate enters and contributes to the ejaculate, (3) the prostatic utricle, which is merely an indentation. These openings are collectively called the verumontanum. | Transitional |

| membranous urethra | A small (1 or 2 cm) portion passing through the external urethral sphincter. This is the narrowest part of the urethra. It is located in the deep perineal pouch. The bulbourethral glands (Cowper's gland) are found posterior to this region but open in the spongy urethra. | Pseudostratified columnar |

spongy urethra (or penile urethra) | Runs along the length of the penis on its ventral (underneath) surface. It is about 15–16 cm in length, and travels through the corpus spongiosum. The ducts from the urethral gland (gland of Littre) enter here. The openings of the bulbourethral glands are also found here.[8] Some textbooks will subdivide the spongy urethra into two parts, the bulbous and pendulous urethra. The urethral lumen runs effectively parallel to the penis, except at the narrowest point, the external urethral meatus, where it is vertical. This produces a spiral stream of urine and has the effect of cleaning the external urethral meatus. The lack of an equivalent mechanism in the female urethra partly explains why urinary tract infections occur so much more frequently in females. | Pseudostratified columnar – proximally, Stratified squamous – distally |

There is inadequate data for the typical length of the male urethra; however, a study of 109 men showed an average length of 22.3 cm (SD = 2.4 cm), ranging from 15 cm to 29 cm.[9]

Female

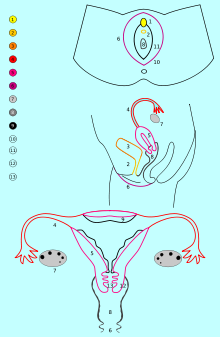

Urethra is number 2, dark yellow

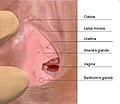

In the human female, the urethra is about 1.9 inches (4.8 cm) to 2 inches (5.1 cm) long and exits the body between the clitoris and the vagina, extending from the internal to the external urethral orifice. The meatus is located below the clitoris. It is placed behind the symphysis pubis, embedded in the anterior wall of the vagina, and its direction is obliquely downward and forward; it is slightly curved with the concavity directed forward. The proximal 2/3rds is lined by transitional epithelium cells while distal 1/3rd is lined by stratified squamous epithelium cells.[10]

The urethra consists of three coats: muscular, erectile, and mucous, the muscular layer being a continuation of that of the bladder. Between the superior and inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm, the female urethra is surrounded by the urethral sphincter. Somatic (conscious) innervation of the external urethral sphincter is supplied by the pudendal nerve.

Histology

The epithelium of the urethra starts off as transitional cells as it exits the bladder. Further along the urethra there are pseudostratified columnar and stratified columnar epithelia, then stratified squamous cells near the external urethral orifice.

There are small mucus-secreting urethral glands, that help protect the epithelium from the corrosive urine.

Development

The urogenital sinus may be divided into three component parts. The first of these is the cranial portion which is continuous with the allantois and forms the bladder proper. In the male the pelvic part of the sinus forms the prostatic urethra and epithelium as well as the membranous urethra and bulbo urethral glands. Part of the vagina in females is also formed from the pelvic part.

Physiology

The urethra is the vessel through which urine passes after leaving the bladder. During urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra relaxes in concert with bladder contraction(s) to forcefully expel the urine in a pressurized stream. Following this, the urethra re-establishes muscle tone by contracting the smooth muscle layer, and the bladder returns to a relaxed, quiescent state. Urethral smooth muscle cells are mechanically coupled to each other to coordinate mechanical force and electrical signaling in an organized, unitary fashion.[11]

Sexual physiology

The male urethra is the conduit for semen during sexual intercourse. It also serves as a passage for urine to flow.[1]

Urine typically contains epithelial cells shed from the urinary tract. Urine cytology evaluates this urinary sediment for the presence of cancerous cells from the lining of the urinary tract, and it is a convenient noninvasive technique for follow-up analysis of patients treated for urinary tract cancers. For this process, urine must be collected in a reliable fashion, and if urine samples are inadequate, the urinary tract can be assessed via instrumentation. In urine cytology, collected urine is examined microscopically. One limitation is the inability to definitively identify low-grade cancer cells and urine cytology is used mostly to identify high-grade tumours.

Clinical significance

Micrograph of urethral cancer (urothelial cell carcinoma), a rare problem of the urethra.

Hypospadias and epispadias are forms of abnormal development of the urethra in the male, where the meatus is not located at the distal end of the penis (it occurs lower than normal with hypospadias, and higher with epispadias). In a severe chordee, the urethra can develop between the penis and the scrotum.- Infection of the urethra is urethritis, said to be more common in females than males. Urethritis is a common cause of dysuria (pain when urinating).

- Related to urethritis is so called urethral syndrome

- Passage of kidney stones through the urethra can be painful, which can lead to urethral strictures.

- Injuries to the urethra (e.g., from a pelvic fracture[12])

Cancer of the urethra.

Foreign bodies in the urethra are uncommon, but there have been medical case reports of self-inflicted injuries, a result of insertion of foreign bodies into the urethra such as an electrical wire.[13]

Investigations

As the urethra is an open vessel with a lumen, investigations of the genitourinary tract may involve the urethra. Endoscopy of the bladder may be conducted by the urethra, called cystoscopy.

Urine cytology.

Catheterization

During a hospital stay or surgical procedure, a catheter may be inserted through the urethra to drain urine from the bladder. The length of a male's urethra, and the fact it contains a prominent bend, makes catheterization more difficult. The integrity of the urethra can be determined by a procedure known as retrograde urethrogram.

Additional images

Position of the urethra in males

Transverse section of the penis

Male urethral opening on glans penis

Female urethral opening within vulval vestibule

Muscles of the female perineum

Urethra. Deep dissection. Serial cross section.

Diagram which depicts the membranous urethra and the spongy urethra of a male

See also

- Perineal urethra

- Vulvovaginal health

- Urethral sponge

- Sexual stimulation: Urethral sounding and Urethral intercourse

- Urethrorrhagia

- Urethrotomy

- Internal urethral orifice

References

^ abcd Marvalee H. Wake (15 September 1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. pp. 583–. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 6 May 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Marianne J. Legato, John P. Bilezikian (editors) (2004). "109: The Evaluation and Treatment of Urinary Incontinence". Principles of Gender-specific Medicine. 1. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 1187.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Chancellor, Michael B.; Yoshimura, Naoki (2004). "Neurophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence". Reviews in Urology. 6(Suppl 3): S19–S28. PMC 1472861. PMID 16985861.

^ Jung, Junyang; Anh, Hyo Kwang; Huh, Youngbuhm (September 2012). "Clinical and Functional Anatomy of the Urethral Sphincter". International Neurourology Journal. 16 (3): 102–106. doi:10.5213/inj.2012.16.3.102. PMC 3469827. PMID 23094214.

^ Karam, I.; Moudouni, S.; Droupy, S.; Abd-Almasad, I.; Uhl, J. F.; Delmas, V. (April 2005). "The structure and innervation of the male urethra: histological and immunohistochemical studies with three-dimensional reconstruction". Journal of Anatomy. 206 (4): 395–403. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00402.x. PMC 1571491. PMID 15817107.

^ Ashton-Miller, J. A.; DeLancey, J. O. (April 2007). "Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1101: 266–296. doi:10.1196/annals.1389.034. PMID 17416924.

^ Moore, Keith (2006). Clinically oriented anatomy : student CD-ROM [CD-ROM] (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-781-73639-8.

^ Atlas of Human Anatomy 5th Edition, Netter.

^ Kohler TS, Yadven M, Manvar A, Liu N, Monga M (2008). "The length of the male urethra". International Braz J Urol. 34 (4): 451–4, discussion 455–6. doi:10.1590/s1677-55382008000400007. PMID 18778496.

^ Manual of Obstetrics. (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1-16.

ISBN 9788131225561.

^ Kyle BD (Aug 2014). "Ion Channels of the Mammalian Urethra". Channels. 8 (5): 393–401. doi:10.4161/19336950.2014.954224. PMC 4594508. PMID 25483582.

^ Stein DM, Santucci RA (July 2015). "An update on urotrauma". Current Opinion in Urology. 25 (4): 323–30. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000184. PMID 26049876.

^ Stravodimos, Konstantinos G; Koritsiadis, Georgios; Koutalellis, Georgios (2009). "Electrical wire as a foreign body in a male urethra: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 3: 49. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-3-49. PMC 2649937. PMID 19192284.

External links

Histology at KUMC epithel-epith07 "Male Urethra"