Jeffersonville, Indiana

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Jeffersonville, Indiana | |

|---|---|

City | |

City of Jeffersonville | |

Skyline of Jeffersonville | |

Nickname(s): The Jeff, Jeff | |

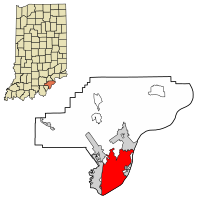

Location of Jeffersonville in Clark County, Indiana. | |

Coordinates: 38°17′44″N 85°43′53″W / 38.29556°N 85.73139°W / 38.29556; -85.73139Coordinates: 38°17′44″N 85°43′53″W / 38.29556°N 85.73139°W / 38.29556; -85.73139 | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Indiana |

| County | Clark |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mike Moore (R) |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 34.38 sq mi (89.06 km2) |

| • Land | 34.10 sq mi (88.31 km2) |

| • Water | 0.29 sq mi (0.74 km2) |

| Elevation | 446 ft (136 m) |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 44,953 |

| • Estimate (2016)[3] | 47,124 |

| • Density | 1,381.98/sq mi (533.59/km2) |

Census | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 47130, 47131, and 47199 |

| Area code(s) | 812 & 930 |

| FIPS code | 18-38358[4] |

GNIS feature ID | 0436979[5] |

| Website | cityofjeff.net |

Jeffersonville is a city in Clark County, Indiana, along the Ohio River. Locally, the city is often referred to by the abbreviated name Jeff. It is directly across the Ohio River to the north of Louisville, Kentucky, along I-65. The population was 44,953 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of Clark County.[6]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Antebellum

1.2 Civil War

1.3 20th century

1.4 Shipbuilding industry

1.5 Annexation

1.6 Big Four Pedestrian Bridge

2 Geography

3 Demographics

3.1 2010 census

3.2 2000 census

4 Dining and bars

5 National Processing Center

6 Notable people

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

History

Statue at Warder Park honoring Thomas Jefferson

Spring St is the main shopping area in downtown

Antebellum

In 1786 Fort Finney was situated where the Kennedy Bridge is today to protect the area from Native Americans, and a settlement grew around the fort. The fort was renamed in 1791 to Fort Steuben in honor of Baron von Steuben. In 1793 the fort was abandoned. Precisely when the settlement became known as Jeffersonville is unclear, but it was probably around 1801, the year in which President Thomas Jefferson took office.[7] In 1802 local residents used a grid pattern designed by Thomas Jefferson for the formation of a city.[8] On September 13, 1803, a post office was established in the city. In 1808 Indiana's second federal land sale office was established in Jeffersonville, which initiated a growth in settling in Indiana that was further spurred by the end of the War of 1812.

Shortly after formation, Jeffersonville was named to be the county seat of Clark County in 1802, replacing Springville. In 1812 Charlestown was named the county seat, but the county seat returned to Jeffersonville in 1878, where it remains.[7]

In 1813 and 1814 Jeffersonville was briefly the de facto capital of the Indiana Territory, as then-governor Thomas Posey disliked then-capital Corydon, and wanting to be closer to his personal physician in Louisville, decided to live in Jeffersonville. However, it is debated by some that Dennis Pennington had some involvement to his location to Jeffersonville.[9] The territorial legislature remained in Corydon and communicated with Posey by messenger.

In 1825, General Lafayette visited Jeffersonville on his United States tour.[10]

Civil War

The Civil War increased the importance of Jeffersonville, as the city was one of the principal gateways to the South during the war, due to its location directly opposite Louisville. It was served by three railroads from the north and had the waterway of the Ohio River. This factor influenced its selection as one of the principal bases for supplies and troops for the Union Army. Operating in the South, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad furnished the connecting link between Louisville and the rest of the South. Camp Joe Holt[11] was instrumental in keeping Kentucky within the Union. The third largest Civil War hospital, Jefferson General Hospital was located in nearby Port Fulton (now within Jeffersonville) from 1864 to 1866,[11] as it was close to the river and Louisville. The original land was seized by the federal government from the Honorable Jesse D. Bright, United States Senator, a sympathizer of the Confederate cause.[11] During the war it housed 16,120 patients in its 5,200 beds and was under the command of Dr. Middleton Goldsmith. A cemetery was built for fallen soldiers down the hill, but the wooden grave markers had decayed by 1927, causing the Jeffersonville city council to build a ball field over the cemetery, and not bothering to move the graves, located on Crestview Avenue. The Jeffersonville Quartermaster Intermediate Depot had its first beginning in the early days of the Civil War, near its present location.

20th century

By 1870, 17% of Jeffersonville residents were foreign-born, mostly from Germany. During the 1920s, Jeffersonville was a popular gathering place for the Ku Klux Klan, as Louisville and New Albany had strong anti-Klan laws and Jeffersonville did not.

City Hall in the Quadrangle complex

Gambling in the 1930s and 1940s was instrumental in Jeffersonville's recovery from the Great Depression and the Flood of 1937. Casinos, betting parlors, night clubs, and even a dog track were present, giving the town the nickname "Little Las Vegas". After Clarence Amster, a New Albany businessman was gunned down on July 2, 1937, public sentiment turned against gambling. On January 2, 1948, Indiana State Police raided every casino in the city before the operators could warn each other, and the judge who had devoted the past nine years to eliminating gambling from Jeffersonville, James L. Bottorff, ensured that the equipment was confiscated and the money at the casinos given to charity. This may have played a factor in keeping Jeffersonville residents from voting to approve riverboat gambling in the 1990s. In 2006, riverboat gambling was approved, but for the return of gambling to occur the Indiana State legislature would either have to approve an additional riverboat, or one of the existing riverboats in Indiana would have to relocate to Jeffersonville; presumably, it would be one of the three currently serving the Cincinnati market.

During World War II, the Quartermaster Depot, in conjunction with Fort Knox, Kentucky housed German prisoners of war until 1945. Now the Depot is used as a shopping center.[12][13]

Shipbuilding industry

Part of Jeffboat in Jeffersonville. Jeffboat is the largest inland shipbuilder in the U.S.

In 1819 the first shipbuilding took place in Jeffersonville, and steamboats would become key to Jeffersonville's economy.[7] In 1834, James Howard built his first steamboat, named the Hyperion, in Jeffersonville.[7] He established his ship building company in Jeffersonville that year but moved his business to Madison, Indiana in 1836 and remained there until 1844. Howard returned his business to the Jeffersonville area to its final location in Port Fulton in 1849. In 1925 the United States Navy assumed control of the Howard Ship Yards until 1941, after Jeffersonville finally annexed Port Fulton.[14] During World War II, the shipyards built landing vessels such as the LST. It was later established as the Jeffersonville Boat & Machine Company, later simply known as Jeffboat, which still supports the local economy.[15] The history of shipbuilding in Jeffersonville is the focus of the Howard Steamboat Museum. There is an annual festival held in September called Steamboat Days that celebrates Jeffersonville's heritage.[16]

Annexation

On February 5, 2008 the city of Jeffersonville officially annexed four out of six planned annex zones.[17] The proposed annexation of the other two zones was postponed due to lawsuits. One of the two areas remaining to be annexed was Oak Park, Indiana an area of about 5,000 more citizens. The areas annexed added about 5,500 acres (22 km2) to the city and about 4,500 citizens, raising the population to an estimated 33,100. The total area planned to be annexed was 7,800 acres (32 km2). The annexed areas received planning and zoning, building permits and drainage issues services immediately, with new in-city sewer rates which are lower. Other services were phased in, such as police and fire, and worked jointly with the pre-existing non-city services until they were available.[18]

The Clark County Courts dismissed the lawsuits against the city on February 25, 2008.[19] This dismissal brought the remaining Oak Park area into the city. The population of the city grew to nearly 50,000 citizens and this was the largest annexation in Jeffersonville's history.

Big Four Pedestrian Bridge

Big Four Station is a park that opened in 2014 at the base of the Big Four Bridge

In February 2011, Kentucky governor Steve Beshear and Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels announced that the two states, along with the City of Jeffersonville, would allocate $22 million in funding to complete the Big Four Bridge project – converting an abandoned railroad bridge into a pedestrian and bicycle path linking Louisville's Waterfront Park and downtown Jeffersonville. Indiana spent $8 million and the City of Jeffersonville spent an extra $2 million in matching funds to pay for construction of a ramp to the Big Four Bridge on the Indiana side.

In July 2012, Jeffersonville City officials unveiled plans for an $8 million plaza, named "Big Four Station", to surround the new ramp. The plaza opened in 2014 and includes a covered playground, fountain, stage, pavilion and plenty of green space. The project has pulled thousands of pedestrians a week into downtown Jeffersonville's main shopping district and has spurred further development. A Marriott motel was built adjacent to the park.

Geography

Jeffersonville is located at 38°17′44″N 85°43′53″W / 38.29556°N 85.73139°W / 38.29556; -85.73139 (38.295669, -85.731485).[20]

According to the 2010 census, Jeffersonville has a total area of 34.354 square miles (88.98 km2), of which 34.06 square miles (88.21 km2) (or 99.14%) is land and 0.294 square miles (0.76 km2) (or 0.86%) is water.[21]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,122 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,020 | 89.4% | |

| 1870 | 7,254 | 80.4% | |

| 1880 | 9,357 | 29.0% | |

| 1890 | 10,666 | 14.0% | |

| 1900 | 10,774 | 1.0% | |

| 1910 | 10,412 | −3.4% | |

| 1920 | 10,098 | −3.0% | |

| 1930 | 11,946 | 18.3% | |

| 1940 | 11,493 | −3.8% | |

| 1950 | 14,685 | 27.8% | |

| 1960 | 19,522 | 32.9% | |

| 1970 | 20,008 | 2.5% | |

| 1980 | 21,220 | 6.1% | |

| 1990 | 21,841 | 2.9% | |

| 2000 | 27,362 | 25.3% | |

| 2010 | 44,953 | 64.3% | |

| Est. 2016 | 47,124 | [3] | 4.8% |

| Source: US Census Bureau | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 44,953 people, 18,580 households, and 11,697 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,319.8 inhabitants per square mile (509.6/km2). There were 19,991 housing units at an average density of 586.9 per square mile (226.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 80.4% White, 13.2% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 1.9% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 4.1% of the population.

There were 18,580 households of which 31.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.1% were married couples living together, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.0% were non-families. 30.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 2.95.

The median age in the city was 37.3 years. 23.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 29.2% were from 25 to 44; 27.5% were from 45 to 64; and 11.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.8% male and 51.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 27,362 people, 11,643 households, and 7,241 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,014.7 people per square mile (777.9/km²). There were 12,402 housing units at an average density of 913.2 per square mile (352.6/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 82.50% White, 13.68% African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.84% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 0.65% from other races, and 1.97% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 1.80% of the population.

There were 11,643 households out of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.3% were married couples living together, 14.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.8% were non-families. 32.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.90.

The age distribution was 23.6% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 31.2% from 25 to 44, 23.8% from 45 to 64, and 12.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $37,234, and the median income for a family was $45,264. Males had a median income of $32,491 versus $24,738 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,656. About 6.9% of families and 10.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.9% of those under age 18 and 7.2% of those age 65 or over.

Dining and bars

Mick's Lounge where Papa John's Pizza began

Jeffersonville has a mix of restaurants that range in popularity along the river front and downtown. The city is scattered with smaller scale bars, restaurants and fast food chains in areas such as Quartermaster Station in which the Town Hall is now located and other shopping centers.[22] Jeffersonville is most known for its being the birthplace of the national pizza chain Papa John's Pizza. The pizza chain started in Mick's Lounge, a local bar in Jeffersonville.

National Processing Center

Jeffersonville is home to the United States Bureau of the Census's National Processing Center, which is the bureau's primary center for collecting, capturing, and delivering data. The facility is one of southern Indiana's largest employers.[23]

Notable people

Ernie Andres, baseball player for Boston Red Sox, basketball player and baseball head coach for Indiana Hoosiers, was born in Jeffersonville.- Jeffersonville is the birthplace of major league pitcher Walt Terrell, NFL wide receiver Jermaine Ross and professional wrestler Nick Dinsmore.

- Musicians Travis Meeks of Days of the New and Duane Roland, a guitarist and founder of Molly Hatchet.

- Former New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan spent part of his childhood in Jeffersonville and actress Natalie West lived in the city at one time.

- Businessman John Schnatter graduated from Jeffersonville High School and started Papa John's in Jeffersonville.

- Jeffersonville politician Richard B. Wathen represented the city in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1973 to 1990. Wathen Park and the Wathen Heights neighborhood are named after his family.

- Evangelist William Branham lived in Jeffersonville for much of his life, and the Branham Tabernacle still stands on the corner of 8th and Penn Streets.

- Admiral Jonas Ingram, Medal of Honor recipient and United States Atlantic Fleet commander during the later years of World War II, was born in Jeffersonville, and attended Jeffersonville High School for a short time prior to attending Culver Military Academy.

- Professional basketball player Mike Flynn, 1971 Indiana Mr. Basketball, Kentucky Wildcats star and Indiana Pacers player, grew up in Jeffersonville.

- Country music star Judy Lynn died at her Jeffersonville home in 2010.

Amanda Ruter Dufour (1822–1899), poet

See also

- Howard Steamboat Museum

- List of cities and towns along the Ohio River

- List of mayors of Jeffersonville, Indiana

- Waterfront Park

- Big Four Bridge

References

^ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 28, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

^ ab "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

^ ab "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

^ abcd "Official History of Jeffersonville". Cityofjeff.net. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

^ Biographical and Historical Souvenir for the Counties of Clark, Crawford, Harrison, Floyd, Jefferson, Jennings, Scott, and Washington, Indiana. Chicago Printing Company. 1889. p. 29.

^ Life of Walter Quintin Gresham, 1832–1895 By Matilda Gresham (Rand, McNally & company 1919) page 23-23

^ Neal, Andrea (May 19, 2014). "Indiana at 200 (25): Marquis de Lafayette a Big Hit in Jeffersonville". Indiana Policy Review. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

^ abc "Camp Joe Holt and Jefferson General Hospital Photographs, 1865, Collection Guide" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

^ "Jeffersonville Quartermaster Intermediate Depot - History and Functions". Qmfound.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

^ "The German Prisoner of war camp in Indiana". Archived from the original on 2011-05-25.

^ "The Howard Ship Yards & Dock Company". Indiana.edu. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

^ "Clark County, Indiana - History". Co.clark.in.us. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

^ http://www.jeffsteamboatdays.com/

^ Jeff absorbs 4 annexed areas (by Harold J. Adams) Courier Journal February 8, 2008

^ Parts of Jeffersonville annexation official (by David Mann) The Evening News February 8, 2008

^ Jeffersonville annexation challenge is rejected (Ben Zion Hershberg) Courier Journal February 26, 2008

^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

^ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

^ "Dining". City of Jeff. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

^ "National Processing Center". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jeffersonville, Indiana. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Jeffersonville. |

- City of Jeffersonville, Indiana website

Jeffersonville, Indiana travel guide from Wikivoyage

Jeffersonville, Indiana travel guide from Wikivoyage- http://www.city-data.com/city/Jeffersonville-Indiana.html

- http://newsandtribune.com/local/x62526264/Growth-Spurt-Census-shows-Clark-County-has-grown-14-3-percent-in-last-decade

Convention and Tourism Bureau[permanent dead link]