Christopher Isherwood

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Christopher Isherwood | |

|---|---|

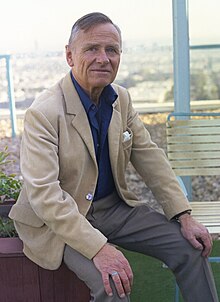

Christopher Isherwood in 1973 | |

| Born | Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood (1904-08-26)26 August 1904 Wyberslegh Hall, High Lane, Cheshire, UK |

| Died | 4 January 1986(1986-01-04) (aged 81) Santa Monica, California, US |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Language | English |

| Citizenship | British (until 1946) American (from 1946) |

| Education | Repton School, Derbyshire |

| Alma mater | Corpus Christi College, Cambridge King's College London |

| Partner | Heinz Neddermeyer (1932–37) Don Bachardy (1953–86) |

| Signature | |

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood (26 August 1904 – 4 January 1986) was an English-American novelist.[1][2] His best-known works include The Berlin Stories (1935–39), two semi-autobiographical novellas inspired by Isherwood's time in Weimar Republic Germany. These enhanced his postwar reputation when they were adapted first into the play I Am a Camera (1951), then the 1955 film of the same name, I am a Camera; much later (1966) into the bravura stage musical Cabaret which was acclaimed on Broadway, and Bob Fosse's inventive re-creation for the film Cabaret (1972). His novel A Single Man was published in 1964 and adapted into the film of the same name in 2009.

Contents

1 Early life and work

2 Life in the United States

3 Later recognition

4 Works

4.1 Translations

4.2 Work on Vedanta and the West

5 Audio and video recordings

6 See also

7 References

7.1 Notes

7.2 Bibliography

8 Further reading

9 External links

Early life and work

Isherwood was born in 1904 on his family's estate close to the Cheshire–Derbyshire border.[3] He was the elder son of Francis Edward Bradshaw Isherwood (1869–1915), known as Frank, a professional officer in the York and Lancaster Regiment who fought in the Boer War and was killed in the First World War, and his wife Kathleen (née Machell Smith; 1868–1960), whose family were successful merchants.[4] Frank Isherwood was the son of John Henry Isherwood, head of the landed gentry family of Isherwood of Marple Hall and Wyberslegh Hall, Cheshire, and a descendant of the regicide John Bradshaw.[5] The Isherwood family estates came into their possession on the marriage of Mary Bradshaw (of the family that had held them for centuries) to Nathaniel Isherwood, a felt-maker from Bolton, Lancashire, in the early 1700s.[6][7]

Repton School

At Repton School in Derbyshire, Isherwood met his lifelong friend Edward Upward with whom he wrote the extravagant "Mortmere" stories, of which one was published during his lifetime, a few others appeared after his death, and others he summarised in Lions and Shadows. He deliberately failed his tripos and left Corpus Christi College, Cambridge without a degree in 1925. For the next few years he lived with violinist André Mangeot, worked as secretary to Mangeot's string quartet and studied medicine. During this time he wrote a book of nonsense poems, People One Ought to Know, with illustrations by Mangeot's eleven-year-old son, Sylvain. It was not published until 1982.

In 1925 A. S. T. Fisher reintroduced him to W. H. Auden,[8][9][10] and Isherwood became Auden's literary mentor and partner in an intermittent, casual liaison. Auden sent his poems to Isherwood for comment and approval. Through Auden, Isherwood met Stephen Spender, with whom he later spent much time in Germany. His first novel, All the Conspirators, appeared in 1928. It was an anti-heroic story, written in a pastiche of many modernist novelists, about a young man who is defeated by his mother. In 1928–29 Isherwood studied medicine at King's College London, but gave up his studies after six months to join Auden for a few weeks in Berlin.

Rejecting his upper class background and embracing his attraction to men, he remained in Berlin, the capital of the young Weimar Republic, drawn by its reputation for sexual freedom. There, he "fully indulged his taste for pretty youths. He went to Berlin in search of boys and found one called Heinz, who became his first great love."[11] Commenting on John Henry Mackay's Der Puppenjunge (The Pansy), Isherwood wrote: "It gives a picture of the Berlin sexual underworld early in this century which I know, from my own experience, to be authentic."[12]

In 1931 he met Jean Ross, the inspiration for his fictional character Sally Bowles. He also met Gerald Hamilton, the inspiration for the fictional Mr Norris. In September 1931 the poet William Plomer introduced him to E. M. Forster. They became close and Forster served as his mentor. Isherwood's second novel, The Memorial (1932), was another story of conflict between mother and son, based closely on his own family history. During one of his return trips to London he worked with the director Berthold Viertel on the film Little Friend, an experience that became the basis of his novel Prater Violet (1945). He worked as a private tutor in Berlin and elsewhere while writing the novel Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935) and a short novel called Goodbye to Berlin (1939), often published together in a collection called The Berlin Stories. These works provided the inspiration for the play I Am a Camera (1951), the 1955 film I am a Camera (both starring Julie Harris), Yes/Buggles' song "Into the Lens/I am a Camera" (1980), the Broadway musical Cabaret (1966) and the film (1972) of the same name. In 1932 he met and fell in love with a young German man named Heinz Neddermeyer.[13]

After leaving Berlin in 1933, he and Heinz moved around Europe, and lived in Copenhagen, Sintra and elsewhere. Heinz was arrested as a draft-evader in 1937 following his brief return to Nazi Germany after he was ejected from Luxembourg as an "undesirable alien". Convicted of "reciprocal onanism",[14] he was sentenced to six months in prison, a year of state labour and two years of compulsory military service.[15] Isherwood collaborated on three plays with Auden: The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), The Ascent of F6 (1936), and On the Frontier (1939). Isherwood wrote a lightly fictionalised autobiographical account of his childhood and youth, Lions and Shadows (1938), using the title of an abandoned novel. Auden and Isherwood traveled to China in 1938 to gather material for their book on the Sino-Japanese War called Journey to a War (1939). In 1939, Auden and Isherwood set sail for the United States on temporary visas, a controversial move, later regarded by some as a flight from danger on the eve of war in Europe.[16]Evelyn Waugh, in his novel Put Out More Flags (1942), included a caricature of Auden and Isherwood as "two despicable poets, Parsnip and Pimpernel", who flee to America to avoid the Second World War.[17]

Life in the United States

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Don Bachardy at nineteen (1954), photographed by Carl Van Vechten

While living in Hollywood, California, Isherwood befriended Truman Capote, an up-and-coming young writer who would be influenced by Isherwood's Berlin Stories, most specifically in the traces of the story "Sally Bowles" that surface in Capote's famed novella, Breakfast at Tiffany's.[18]

Isherwood also had a close friendship with the British writer Aldous Huxley, with whom he sometimes collaborated. Gerald Heard had introduced Huxley to Vedanta (Upanishad-centered philosophy) and meditation. Huxley became a Vedantist in the circle of Hindu Swami Prabhavananda, and introduced Isherwood to the Swami's Vedanta circle.[19] Isherwood became a convinced Vedantist himself and adopted Prabhavananda as his own guru, visiting the Swami every Wednesday for the next 35 years and collaborating with him on a translation of the Bhagavad Gita.[20] The process of conversion to Vedanta was so intense that Isherwood was unable to write another novel between the years 1939-1945, while he immersed himself in study of the Vedas.[21]

Isherwood also befriended Dodie Smith, a British novelist and playwright who had also moved to California, and who became one of the few people to whom Isherwood showed his work in progress.[22]

Isherwood considered becoming an American citizen in 1945 but balked at taking an oath that included the statement that he would defend the country. The next year he applied for citizenship and answered questions honestly, saying he would accept non-combatant duties like loading ships with food. The fact that he had volunteered for service with the Medical Corps helped as well. At the naturalisation ceremony, he found he was required to swear to defend the nation and decided to take the oath since he had already stated his objections and reservations. He became an American citizen on 8 November 1946.[23]

He began living with the photographer William "Bill" Caskey. In 1947, the two traveled to South America. Isherwood wrote the prose and Caskey took the photographs for a 1949 book about their journey entitled The Condor and the Cows.

On Valentine's Day 1953, at the age of 48, he met teenaged Don Bachardy among a group of friends on the beach at Santa Monica. Reports of Bachardy's age at the time vary, but Bachardy later said, "At the time I was probably 16."[24]. In fact, he was 18.[25] Despite the age difference, this meeting began a partnership that, though interrupted by affairs and separations, continued until the end of Isherwood's life.[26]

During the early months of their affair, Isherwood finished—and Bachardy typed—the novel on which he had worked for some years, The World in the Evening (1954). Isherwood also taught a course on modern English literature at Los Angeles State College (now California State University, Los Angeles) for several years during the 1950s and early 1960s.

The 30-year age difference between Isherwood and Bachardy raised eyebrows at the time, with Bachardy, in his own words, "regarded as a sort of child prostitute,"[27] but the two became a well-known and well-established couple in Southern Californian society with many Hollywood friends.

Down There on a Visit, a novel published in 1962, comprised four related stories that overlap the period covered in his Berlin stories. In the opinion of many reviewers, Isherwood's finest achievement was his 1964 novel A Single Man, that depicted a day in the life of George, a middle-aged, gay Englishman who is a professor at a Los Angeles university.[28] The novel was adapted into the film, A Single Man, in 2009. During 1964 Isherwood collaborated with American writer Terry Southern on the screenplay for the Tony Richardson film adaptation of The Loved One, Evelyn Waugh's caustic satire on the American funeral industry.

Isherwood and Bachardy lived together in Santa Monica for the rest of Isherwood's life. Isherwood was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1981, and died of the disease on 4 January 1986 at his Santa Monica home, aged 81. His body was donated to medical science at UCLA, and his ashes were later scattered at sea.[29] Bachardy became a successful artist with an independent reputation, and his portraits of the dying Isherwood became well known after Isherwood's death.[30]

Plaque, Nollendorfstraße 17. Christopher Isherwood lived here between March 1929 and January/February 1933.

Later recognition

- The house in the Schöneberg district of Berlin where Isherwood lived bears a memorial plaque to mark his stay there between 1929 and 1933.

- The 2008 film Chris & Don: A Love Story chronicled Isherwood and Bachardy's lifelong relationship.

A Single Man was adapted into a film A Single Man in 2009.- In 2010 Isherwood's autobiography, Christopher and His Kind, was adapted into a television film by the BBC, starring Matt Smith as Isherwood and directed by Geoffrey Sax.[31] It was broadcast in France and Germany on the Arte channel in February 2011, and in Britain on BBC 2 the following month.

Works

All the Conspirators (1928; new edition 1957 with new foreword)

The Memorial (1932)

Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935; U.S. edition titled The Last of Mr Norris)

The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935, with W. H. Auden)

The Ascent of F6 (1937, with W. H. Auden)

Sally Bowles (1937; later included in Goodbye to Berlin)

On the Frontier (1938, with W. H. Auden)

Lions and Shadows (1938, autobiography)

Goodbye to Berlin (1939)

Journey to a War (1939, with W. H. Auden)

Bhagavad Gita, The Song of God (1944, with Prabhavananda)

Vedanta for Modern Man (1945)

Prater Violet (1945)

The Berlin Stories (1945; contains Mr Norris Changes Trains and Goodbye to Berlin; reissued as The Berlin of Sally Bowles, 1975)

Vedanta for the Western World (Unwin Books, London, 1949, ed. and contributor)

The Condor and the Cows (1949, South-American travel diary)

What Vedanta Means to Me (1951, pamphlet)

The World in the Evening (1954)

Down There on a Visit (1962)

An Approach to Vedanta (1963)

A Single Man (1964)

Ramakrishna and His Disciples (1965)

Exhumations (1966; journalism and stories)

A Meeting by the River (1967)

Essentials of Vedanta (1969)

Kathleen and Frank (1971, about Isherwood's parents)

Frankenstein: The True Story (1973, with Don Bachardy; based on their 1973 film script)

Christopher and His Kind (1976, autobiography), published by Sylvester & Orphanos

My Guru and His Disciple (1980)

October (1980, with Don Bachardy)

The Mortmere Stories (with Edward Upward) (1994)

Where Joy Resides: An Isherwood Reader (1989; Don Bachardy and James P. White, eds.)

Diaries: 1939–1960, Katherine Bucknell, ed. (1996)

Jacob's Hands: A Fable (1997) originally co-written with Aldous Huxley

Lost Years: A Memoir 1945–1951, Katherine Bucknell, ed. (2000)

Lions and Shadows (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000)

Kathleen and Christopher, Lisa Colletta, ed. (Letters to his mother, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press], 2005)

Isherwood on Writing (University of Minnesota Press, 2007)

The Sixties: Diaries:1960-1969 Katherine Bucknell, ed. 2010

Liberation: Diaries:1970-1983 Katherine Bucknell, ed. 2012

The Animals: Love Letters Between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, Edited by Katherine Bucknell (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014)

Translations

Charles Baudelaire, Intimate Journals (1930; revised edition 1947)

The Song of God: Bhagavad-Gita (with Swami Prabhavananda, 1944)

Shankara's Crest-Jewel of Discrimination (with Swami Prabhavananda, 1947)

How to Know God: The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali (with Swami Prabhavananda, 1953)

Work on Vedanta and the West

Vedanta and the West was the official publication of the Vedanta Society of Southern California. It offered essays by many of the leading intellectuals of the time and had contributions from Aldous Huxley, Gerald Heard, Alan Watts, J. Krishnamurti, W. Somerset Maugham, and many others. Isherwood was Managing Editor from 1943 until 1945. Together with Huxley and Heard, he served on the Editorial Advisory Board from 1951 until 1962.

Isherwood wrote the following articles that appeared in Vedanta and the West:

|

|

In 1948 several articles from Vedanta and the West were issued in book form as Vedanta for the Western World. Isherwood edited the selection and provided an introduction and three articles ("Hypothesis and Belief," "Vivekananda and Sarah Bernhardt," "The Gita and War"). Other contributors included Aldous Huxley, Gerald Heard, Swami Prabhavananda, Swami Vivekananda et al.

Audio and video recordings

Christopher Isherwood reads selections from the Bhagavad Gita – CD[32]

Christopher Isherwood reads selections from the Upanishads – CD[32]- Lecture on Girish Ghosh – CD[33][34]

Christopher Isherwood Reads Two Lectures on the Bhagavad Gita by Swami Vivekananda – DVD

See also

LGBT portal

LGBT portal

References

Notes

^ Berg, James J. ed., Isherwood on Writing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 19

^ Obituary Variety (15 January 1986)

^ Parker, Peter. Isherwood. Picador: 2004 .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 0-330-32826-3 p. 6

^ Kathleen and Frank, Christopher Isherwood, 2013, Vintage Books, pg 3

^ Kathleen and Frank, Christopher Isherwood, 2013, Vintage Books, pp. xi, 306, 309

^ Kathleen and Frank, Christopher Isherwood, 2013, Vintage Books, p. 303

^ http://www.marple-uk.com/Hall1.htm

^ "Consolidated index". Oxford Poetry. Graham Nelson. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

^ James, Callum (10 September 2012). "Ambassador of Loss by Michael Scarrott". Front Free Endpaper. Blogspot. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

^ "W. H. Auden". Helensburgh Heroes. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

^ Bate, Jonathan (28 May 2004). "Hello to Berlin, boys and books". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

^ Hubert Kennedy, Mackay, John Henry in glbtq.com Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Mackay's work was "a classic boy-love novel set in the contemporary milieu of boy prostitutes in Berlin."

^ Fryer, p. 128

^ Christopher and His Kind, p. 287

^ Fryer, p. 168

^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1981). W. H. Auden: A Biography. George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-928044-9.

^ "Christopher Isherwood Is Dead at 81". The New York Times. 6 January 1986. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

^ Norton, Ingrid (1 July 2010). "Year with Short Novels: Breakfast at Sally Bowles'". Open Letters Monthly. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

^ Braubach, Mary Ann. "Huxley on Huxley". Cinedigm, 2010. DVD.

^ "Christopher Isherwood 1904–1986; Vedantist Writer/Seeker, An Inner Man of Wit, Warmth and Depth". Hinduism Today. Himalayan Academy. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

^ Izzo, David Garrett (2001). Christopher Isherwood: His Era, His Gang, and the Legacy of the Truly Strong Man. Univ of South Carolina Press. pp. 163–64. ISBN 978-1570034039. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

^ "Christopher Isherwood", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed on 3 March 2014

^ Bucknell (ed.), pp.40, 77–8

^ The biographical film Chris & Don: A Love Story

^ Bachardy was born in May 1934, meaning that in February 1953 he was 18

^ Peter Parker, Isherwood, 2004

^ "The First Couple: Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood", by Armistead Maupin, The Village Voice, Volume 30, Number 16, 2 July 1985.

^ "The Britons who made their mark on LA". 2011-09-11. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 23105). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

^ Bachardy, Don, Christopher Isherwood: Last Drawings, Faber and Faber: 1990,

ISBN 978-0571140756

^ [1] BBC Press Release for "Christopher and His Kind"

^ ab CD produced by mondayMEDIA, distributed on the GemsTone label

^ Lecture given in the Santa Barbara Vedanta Temple

^ "Review in". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

Bibliography

- Fryer, Jonathan (1977), Isherwood: A Biography, Garden City, NY, Doubleday & Company.

ISBN 0-385-12608-5.

Further reading

- Berg, James J. and Freeman, Chris eds, Conversations with Christopher Isherwood (2001)

- Berg, James J. and Freeman, Chris eds. The Isherwood century: essays on the life and work of Christopher Isherwood (2000)

- Finney, Brian. Christopher Isherwood: A Critical Biography (1979)

- Marsh, Victor. Mr Isherwood Changes Trains: Christopher Isherwood and the search for the 'home self (2010) Clouds of Magellen

ISBN 9780980712056 - Page, Norman. Auden and Isherwood: The Berlin Years (2000)

- Parker, Peter. Isherwood: A Life (2004)

- Prosser, Lee. Isherwood, Bowles, Vedanta, Wicca, and Me (2001)

ISBN 0-595-20284-5 - Prosser, Lee. Night Tigers (2002)

ISBN 0-595-21739-7

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Christopher Isherwood |

Christopher Isherwood on IMDb

Christopher Isherwood at the Internet Broadway Database

Christopher Isherwood at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

Summers, Claude J. "Isherwood, Christopher (1904-1986)". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

Summers, Claude J. (1 February 2010). "A Single Man: Ford's Film / Isherwood's Novel". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

Isherwood Exhibit at the Huntington Archived 25 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

W.I. Scobie (Spring 1974). "Christopher Isherwood, The Art of Fiction No. 49". The Paris Review.- LitWeb.net: Christopher Isherwood Biography

- Christopher Isherwood Foundation

Christopher Isherwood Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

"Huxley on Huxley". Dir. Mary Ann Braubach. Cinedigm, 2010. DVD.

Where Joy Resides An Isherwood Reader

"Cabaret Berlin" Information on Christopher Isherwood and the entertainment of the Weimar era