Brighton Beach

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Brighton Beach | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood in Brooklyn | |

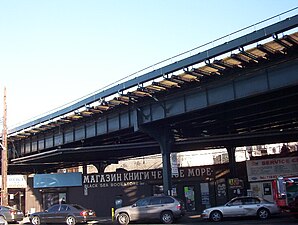

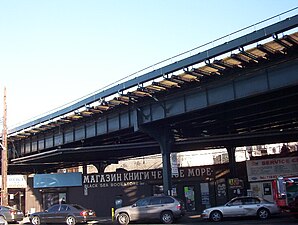

Looking east along Brighton Beach Avenue from the corner of Coney Island Avenue | |

Brighton Beach Location Show map of New York City  Brighton Beach Brighton Beach (New York) Show map of New York  Brighton Beach Brighton Beach (the US) Show map of the US | |

Coordinates: 40°34′39″N 73°57′41″W / 40.57750°N 73.96139°W / 40.57750; -73.96139Coordinates: 40°34′39″N 73°57′41″W / 40.57750°N 73.96139°W / 40.57750; -73.96139 | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | |

| Borough | |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 35,547 |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 |

| ZIP code | 11235 |

| Telephone area code | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

Brighton Beach is an oceanside neighborhood in the southern portion of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, along the Coney Island peninsula. According to the 2010 United States Census report, the Brighton Beach and Coney Island area, combined, had more than 110,000 residents. Brighton Beach is bounded by Coney Island proper at Ocean Parkway to the west, Manhattan Beach at Corbin Place to the east, Sheepshead Bay at the Belt Parkway to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the south along the beach and boardwalk.

It is known for its high population of Russian-speaking immigrants, and as a summer destination for New York City residents due to its beaches along the Atlantic Ocean and its proximity to the amusement parks in Coney Island.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Early development

1.2 Early 20th century

1.3 Late 20th century and Soviet immigration

2 Culture

2.1 Russian-speaking cultures

2.2 Demographics

2.3 Theater

3 Crime

4 Transportation

5 Education

6 In popular culture

7 Notable residents

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

History

Early development

Brighton Beach is included in an area from Sheepshead Bay to Sea Gate that was purchased from the Natives Americans in 1645 for a gun, a blanket and a kettle.[2]

Brighton Beach was located on sandy terrain, and before development in the 1860s, had mostly farms. The area was part of the "Middle Division" of the town of Gravesend, which was the sole English settlement out of the original six towns in Kings County. By the mid-18th century, thirty-nine lots in the division had been distributed to the descendants of English colonists.[3]

In 1868, William A. Engeman built a resort in the area.[4] The resort was given the name "Brighton Beach" in 1878 by Henry C. Murphy and a group of businessmen, who chose to name as an allusion to the English resort city of Brighton.[5][6] With the help of Gravesend's surveyor William Stillwell, Engeman acquired all 39 lots for the relatively low cost of $20,000.[7][8]:38 This 460-by-210-foot (140 by 64 m) hotel, with rooms for up to 5,000 people nightly and meals for up to 20,000 people daily, was close to the then-rundown western Coney Island, so it was mostly the upper middle class that went to this hotel.[3] The 400-foot (120 m), double-decker Brighton Beach Bathing Pavilion was also built nearby and opened in 1878, with the capacity for 1,200 bathers.[9][8]:38[6] "Hotel Brighton", also known as the "Brighton Beach Hotel", was situated on the beach at what is now the foot of Coney Island Avenue.[4] The Brooklyn, Flatbush, and Coney Island Railway, the predecessor to the New York City Subway's present-day Brighton Line, opened on July 2, 1878, and provided access to the hotel.[10][8]:38[11]

Adjacent to the hotel, Engeman built the Brighton Beach Race Course for thoroughbred horse racing.[4] In December 1887, an extremely high tide washed over the area, creating a new, temporary connection between Sheepshead Bay and the ocean. Wrote the Brooklyn Daily Eagle: "Unless [Engeman] is very lucky the next races on the Brighton Beach track will be conducted by the white crested horses of Neptune."[12]

After that extremely high tide, and a decade of beach erosion, the Brighton Beach Hotel, by then owned by the Railway, faced the possibility of being "undermined and carried away."[13][14] A plan termed "highly ingenious and novel" was initiated by the superintendent of the Railway, J.L. Morrow, and its Secretary, E.L. Langford, to elevate and move the building as a whole, 495 feet further inland. This was accomplished by lifting the estimated 5000 ton, 460 by 150 feet (140 m × 46 m) building, using 13 hydraulic jacks, after which 24 lines of railroad track – a mile and a half length in total – were laid under it, and 112 railroad "platform cars" (flat cars) pulled by six steam locomotives were used to pull the hotel away from the sea.[13] This careful engineering (by B.C. Miller) made the move successful; it began on April 2, 1888, and continued for the next nine days, and was the largest building move of the 19th century.[15]

Anton Seidl and the Metropolitan Opera brought their popular interpretations of Wagner to the Brighton Beach Music Hall, where John Philip Sousa was in residence, and the New Brighton Theater was a hotspot for vaudeville. Visitors for tea at Reisenweber’s Brighton Beach Casino would be served by Japanese waitresses in full costume. At an enormous private club, the Brighton Beach Baths, members could swim, access a private beach, and play handball, mah-jongg, and cards.[3]

The village, along with the rest of Gravesend, was annexed into the 31st Ward of the City of Brooklyn in 1894.[16]

Early 20th century

In 1905, Brighton Beach Park opened its own area of amusements, calling it Brighton Pike. Brighton Pike offered a boardwalk, games, live entertainment (including the Miller Brothers’ wild-west show (101 Ranch), and a huge steel roller coaster. The park was shut down in 1919 after it burned down.[3] The actual beach remained popular, though.[6]

Brighton Beach was re-developed as a fairly dense residential community with the final rebuilding of the Brighton Beach railway to rapid transit standards, becoming the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) Brighton Line (B and Q services) of the New York City Subway c. 1920. The subway system in the neighborhood is above ground on an elevated structure. The opening of the BMT Brighton Line had conflicting consequences: although it made Brighton Beach viable as a year-round community, it was now much more feasible for visitors to return home in the evening rather than spend the night. This led to the closure of the Brighton Beach Hotel in 1924.[3]

The years just before and following the Great Depression brought with them a neighborhood consisting mostly of first- and second-generation Jewish-Americans and, later, Holocaust concentration camp survivors.[17][18] Of the estimated 55,000 Holocaust survivors living in New York City as of 2011, most live in Brighton Beach.[19] To meet the bursting cultural demands, the New Brighton Theater converted itself to the States' first Yiddish theater in 1919.[3][17]

Late 20th century and Soviet immigration

The "Millennium Theater", now the "Master Theater"

After World War II, the quality of life in Brighton Beach decreased significantly as the poverty rate and the ratio of older residents to younger residents increased.[6] Due to the 1970s fiscal crisis, government workers and the middle class had moved to suburban areas, while people subdivided houses into single room occupancy residences for the poor, the elderly, and the mentally ill. Brighton Beach suffered from arson as much as it did from constant drug trades.[6] During the summer, however, people from all around the city went to Brighton Beach's beach next to the Atlantic Ocean.[6]

In the mid-1970s, Brighton Beach became a popular place to settle for the Soviet immigrants, mostly Jews from Russia and Ukraine.[6] So many ex-Soviets immigrated to Brighton Beach that the area became known as "Little Odessa" (after the Ukrainian city on the Black Sea).[6]

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent significant changes in the social and economic circumstances of post-Soviet states led thousands of former Soviet citizens to immigrate to the United States.[6] Many more of the Soviet and post-Soviet immigrants, who primarily spoke Russian, chose Brighton Beach as a place to settle.

A large number of Russian-speaking, immigrant-oriented firms, shops, restaurants, clubs, offices, banks, schools, and children's play centers opened in the area.[20] The value of real estate in Brighton Beach started to rise again, even though drugs remained a social issue in the area through the early 1990s.[6]

In the early 2000s, a high-income ocean-front condominium complex, the "Oceana", was constructed.[21] This address has become the destination of wealthy businessmen, entertainers, and senior officials from the former Soviet Union, and with their purchase of units at the Oceana, area housing prices have risen.[20]

Since the early 2010s, a significant number of Central Asian immigrants have also chosen Brighton Beach as a place to settle.[20]

Culture

The proximity of Brighton Beach to the city's beaches—Brighton Beach Avenue runs parallel to the Coney Island beach and boardwalk[22]—and the fact that the neighborhood is directly served by a subway station makes it a popular summer weekend destination for New York City residents.[6]

- Brighton Beach's culture

Russian stores in Brighton Beach

Backgammon players at Second Street Park in 2012

A Russian-language bookstore under the New York City Subway tracks on Coney Island Avenue in Brighton Beach

Crowded Brighton Beach on a summer afternoon

Water sports on Brighton Beach

- Brighton Beach housing

The Oceana luxury condominiums on Brighton Beach, built in the early 2000s

Juxtaposition of apartments and private homes

Brighton 15th Street

Russian-speaking cultures

A Brighton Beach storefront's sign, which contains both its English and its Russian names

As apartment buildings started to be built in large numbers in the 1930s, many of those who moved into the neighborhood were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, often by way of the Lower East Side. They came from many countries, but also set the stage for a later wave of immigration from the Soviet Union that started in the 1970s, when Brighton Beach became known as "Little Odessa,"[23] and "Little Russia".[24] An annual festival, the Brighton Jubilee, celebrates the area's Russian-speaking heritage.[3] The area has also been called "the land of pelmeni, matryoshkas, tracksuits, and...vodka" due to its large population of Soviet immigrants.[25]

In 2006, Alec Brook-Krasny was elected for the 46th District of the New York State Assembly, which includes Brighton Beach, becoming the country's first elected Soviet-born politician.[26]

Demographics

As of 1983[update], Brighton Beach had a middle class, mostly Jewish, older population. 27% of Brighton Beach was of age 62 or older, while the national average of persons aged 62 or older was 13.9%.[27] Since the 1990s, however, the neighborhood's ethnic demographics have been changing, with a large influx of mainly Muslim immigrants from Central Asia, such as Uzbeks.[20] In subsequent years, the proportion of whites leveled out, the proportion of the black population decreased significantly, and the proportion of the Asian population increased to 14% as of 2014.[28] As of 2010[update], increasing numbers of Muslim Central Asians were moving into Brighton Beach, and based on the historic Soviet influence over these area, these immigrants also speak Russian.[20][29]

According to the United States Census report of 2010, Brighton Beach and Coney Island, combined, had 111,063 residents as of 2009.[30] In that year, the median age of residents of Brooklyn was 34.2 and in New York City as a whole, it was 36.0 years, while in the combined Brighton Beach and Coney Island area it was 47.9 years.[30] hence, the area is distinguished by a higher median age of its population. As DiNapoli and Bleiwas note in a city report, "the number of residents aged 65 years and older in [this area] rose by 4.1 percent, so that senior citizens accounted for more than one-quarter of the area’s population" at that date.[30] According to the census, the population density in Brighton Beach, per se (52,109 people per square mile), was almost twice the average population density of New York City (27,012 people per square mile), though the average household size was 2.1 people, lower than the city average of 2.6 people. The average income of households in the area was $36,574, while the average income in the whole city was $55,217, according to the 2010 census.[31] In Brighton Beach, 21% of the population lives below the poverty line,[28] compared to only 15.4% citywide.[32]

Most of the population of Brighton Beach are immigrants. Less than a quarter (23.3%) of Brighton Beach residents were born in the United States, and nearly three-quarters were born abroad (72.9%). Because of this, English language proficiency in Brighton Beach is lower than the city average. More than a third (36.1%) of the population of Brighton Beach does not speak or understand English, while citywide, only one in fourteen people (7.2%) cannot speak or understand English.[30]

Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Brighton Beach was 35,547, an increase of 303 (0.9%) from the 35,244 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 393.32 acres (159.17 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 90.4 inhabitants per acre (57,900/sq mi; 22,300/km2).[1]

The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 69.7% (24,774) White, 1.0% (352) African American, 0.2% (61) Native American, 12.9% (4,580) Asian, 0.0% (10) Pacific Islander, 0.4% (139) from other races, and 1.2% (442) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14.6% (5,189) of the population.[33]

Theater

The Brighton Ballet Theater, established in 1987, is one of the most famous Russian ballet schools in the United States.[34] More than 3,000 children have trained in ballet, modern and character dances, and folk dances here.[34]

A Russian-speaking theater near the waterfront, Master Theater,[35] features performances by actors from the U.S., Russia, and other countries.[36]

Crime

Brighton Beach is patrolled by the New York City Police Department's 60th Precinct.[37] The crime statistics for 2014 indicated that there were 10 murders, 21 rapes, 267 robberies, 314 felony assaults, 193 burglaries, 592 grand larcenies, and 68 grand larcenies auto in the 60th Precinct in this time frame.[38]

Brighton Beach is considered a hot spot for the "Russian Mafia",[39] though public perception has been that organized crime "has largely gone away."[40] In the 1970s, the most notorious leg of the mafia was the Potato Bag Gang,[41] which served as a robbery gang for larger Russian crime syndicates in New York City. Marat Balagula was a crime boss from Brighton Beach who denies having any connection to the American Mafia or the Russian-speaking Mafia.[citation needed]The major Russian criminal element in Brighton Beach was the international Russian mafia group, known as vor v zakone or "vory," and the first vory crime boss in Brighton Beach was Evsei Agron, who controlled the area's crime during the 70s and 80s until his death in 1985.[42] After the fall of the Soviet Union in the 90s, many ethnic Russian criminals illegally entered the United States, coming especially to Brighton Beach.[citation needed] The infamous vor Vyacheslav Ivankov, who dominated the Brighton Beach underworld until his arrest in 1995, arrived during this wave.[43]

Transportation

The New York City Subway's B and Q trains serve the neighborhood at the Brighton Beach and Ocean Parkway stations. Both are located on the elevated Brighton Line structure over Brighton Beach Avenue.[44] Buses serving Brighton Beach include the B1, B36, B49 and B68.[45]

Education

Brighton Beach is served by the New York City Department of Education. Primary and middle schools within Brighton Beach include PS 225 The Eileen E. Zaglin School for grades K-8,[46][47] and the P.S. 253 Ezra Jack Keats International School.[48] In 1983, the Community School District 21 operated PS 225, PS 253, and Junior High School 302.[27] During that year, over 62% of its students read at or above their grade level, far above the national average.[27] Schools near Brighton Beach within Coney Island are PS 100, The Coney Island School for grades K-5[49][50][51][52] and Intermediate School 303 Herbert S. Eisenberg.[51][53][54][54]William E. Grady Vocational High School, a vocational high school, is located in Brighton Beach.[55]Abraham Lincoln High School, an academic high school, is in Coney Island.[51][56] In 1983 Lincoln was the zoned academic high school of Brighton Beach.[27] Other nearby high schools include the Rachel Carson High School for Coastal Studies[57] and The Leon M. Goldstein High School for the Sciences.[58]

Brooklyn Public Library also operates the Brighton Beach Library.[59]

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .mw-module-gallerydisplay:block!important;float:none!important.mw-parser-output .mw-module-gallery divdisplay:inherit!important;float:none!important;width:auto!important

In popular culture

The neighborhood has been mentioned or appears many times in popular culture:

Films:- Brighton Beach is featured in the Russian spy-comedy film Weather Is Good on Deribasovskaya, It Rains Again on Brighton Beach (1992).[60]

- The film Little Odessa (1994) is set in Brighton Beach.[61]

- In the film Maximum Risk (1996), starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, the main character faces off against the Russian Mob in Brighton Beach.[62]

- The film Requiem for a Dream (2000) is largely set in Brighton Beach.[63]

- In the film Two Lovers (2008), the action takes place in Brighton Beach.[64]

- Brighton Beach is featured in the 2005 drama Lord of War starring Nicolas Cage, where the protagonist and his family immigrated to from Ukraine in order to escape the Soviet Union.[65]

Literature:- In Robin Cook's novel Vector (2000), disillusioned former Russian biochemical worker Yuri Davydov develops weapons-grade anthrax in the basement of his Brighton Beach home.[66]

Hubert Selby's novel Requiem for a Dream is set in Brighton Beach during the 1970s.

Plays:

Neil Simon's play Brighton Beach Memoirs (1983), which won two Tony awards in 1983, as well as its 1986 film adaptation, are both set against the backdrop of Brighton Beach during the Great Depression, in 1937.[27]

Television:- A Lifetime reality TV show called Russian Dolls, documenting the lives of young Russian-Americans and a group of Brighton Beach housewives spending time in a popular Russian nightclub, Rasputin Restaurant, premiered August 11, 2011.[67]

Video Games:- A fictionalized version of Brighton Beach, known as Hove Beach, is a neighborhood in the 2008 video game Grand Theft Auto IV.

Notable residents

Notable current and former residents of Brighton Beach include:

Marat Balagula (born 1943), neighborhood mob boss during the 1980s[citation needed]

Adele Cohen (born 1942), member of the New York State Assembly, representing the 46th district, from to 1998 to 2006[citation needed]

Eddie Daniels (born 1941), clarinettist and saxophonist[68]

Neil Diamond (born 1941), songwriter, musician artist grew up in Brighton Beach

Howard Greenfield (1936–1986), songwriter[69]

Alfred Harvey (1913-1994), founder of Harvey Comics

David B. Hollander (1913-2009), longest active pulpit rabbi in America[70]

Vyacheslav Ivankov (1940–2009), alleged crime boss

Jack Kirby (1917–1994), comic book artist, co-creator of Captain America during the early 1940s and the Fantastic Four, X-Men, and Incredible Hulk in the 1960s

Sergei Kobozev (1964-1995), Russian boxer

Arthur Miller (born 1915), writer

Lea Bayers Rapp (born 1946), author, journalist, playwright[71]

Vladimir Reznikov, Russian-American hitman, murdered outside of the infamous Odessa Restaurant in 1986.[72]- Lynn Ross (stage name), dancer in the original 1957 Broadway production of West Side Story[73]

Neil Sedaka (born 1939), songwriter[74]

Willi Tokarev (born 1934), Russian singer-songwriter

The Tokens, vocal group formed in 1955 at Abraham Lincoln High School[75]

Jerry Wurf, U.S. labor leader and president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) from 1964 to 1981.

See also

- Coney Island and Brooklyn Railroad

- Russian diaspora

References

^ ab Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

^ Douglass, Harvey (1933). "Coney Island Scenes Shift, Never Change". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (online, 23 March). Retrieved March 23, 2016.

^ abcdefg Williams, Keith. "Brighton Beach: Old World mentality, New World reality". The Weekly Nabe. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

^ abc Stanton, Jeffrey (1997). "Coney Island — Luxury Hotels". Coney Island History Site. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ Weinstein, Stephen (2000). "Brighton Beach". In Jackson, Kenneth T.; Keller, Lisa; Flood, Nancy. The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New York, NY, and New Haven, CT, USA: The New York Historical Society and Yale University Press. pp. 139–140. ISBN 0-300-11465-6. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ abcdefghijk "Brighton Beach History". Our Brooklyn. Brooklyn Public Library. 1936-08-30. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

^ "The Real Brighton Beach". The New Yorker. 2010-03-29. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

^ abc Phalen, William (2016). Coney Island : 150 years of rides, fires, floods, the rich, the poor and finally Robert Moses. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-9816-1. OCLC 933438460.

^ "Engeman's New Bathing Hotel". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 1, 1878. p. 1. Retrieved 2018-07-23 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

^ Feinman, Mark S. (February 17, 2001). "Early Rapid Transit in Brooklyn, 1878–1913". nycsubway.org. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "ANOTHER CONEY ISLAND RAILROAD.; OPENING OF THE BROOKLYN AND FLATBUSH LINE TO BRIGHTON BEACH". The New York Times. July 2, 1878. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ "High Tides". Brooklyn Daily Eagle (December 7). 1887. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

^ ab "Moving the Brighton Beach Hotel". Scientific American. New York: Scientificamerican.com. April 14, 1888. Retrieved November 12, 2015.Reprinted as "A Hotel on Wheels," in The Engineer (London, ENG), April 27, 1888

(subscription required)

^ "Brighton Beach". Arrts-arrchives.com. May 11, 2004. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "The Big Hotel on Wheels". The New York Times. April 4, 1888. Retrieved November 12, 2015. (subscription required)

^ Appleton's Dictionary of New York and Vicinity. 1904. p. 66. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ ab "Coney Island and the Jews". Internet Archive. November 27, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

^ Nancy Foner (2001). New Immigrants in New York. Google Books. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231124157. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ Suddath, Claire (2010). "The Plot to Cheat Germany's Holocaust Survivors' Fund". Time (online, November 13). Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ abcde Larson, Michael; Liao, Bingling; Stulberg, Ariel; Kordunsky, Anna (2012). "Changing Face of Brighton Beach: Central Asians Join Russian Jews in Brooklyn Neighborhood". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ Sheftell, Jason (2008). "Oceana - a residential resort village off Brighton Beach's main drag". Daily News. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ Google (November 11, 2015). "Brighton Beach Ave" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ Ortiz, Brennan (2014). "NYC's Micro Neighborhoods: Little Odessa in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn". Untapped Cities (online, January 23). Retrieved September 9, 2014.

^ Johnstone, Sarah (2005). Ukraine. Melbourne, AUS: Lonely Planet. p. 119.

^ Idov, Michael (2009). "New York Guides: The Everything Guide to Brighton Beach". New York (magazine, online, April 13). Retrieved November 12, 2015.Subtitle: Inside the land of pelmeni, matryoshkas, tracksuits, and of course, vodka.

^ Conn, Phyllis (2012). DeSena, Judith, ed. The Dual Roles of Brighton Beach: A Local and Global Community. The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 352. ISBN 9780739166703.

^ abcde Dolan, Dolores. (1983). "If You're Thinking of Living in Brighton Beach". The New York Times (online, June 19). Retrieved October 15, 2012.

^ ab "Census profile: NYC-Brooklyn Community District 13--Brighton Beach & Coney Island PUMA, NY". Census Reporter. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

^ [1] Archived March 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

^ abcd DiNapoli, Thomas P.; Bleiwas, Kenneth B. (2011). Economic Snapshot of Coney Island and Brighton Beach [Report 8-2012, July 2011] (PDF). New York, NY, USA: Office of the State Comptroller, New York City Public Information Office. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "11235 Zip Code (New York, New York) Profile - homes, apartments, schools, population, income, averages, housing, demographics, location, statistics, sex offenders, residents and real estate info". www.city-data.com. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

^ "New York Report - 2016 - Talk Poverty". Talk Poverty. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

^ Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

^ ab See:

Peretti, Viviana (2011). "Russian Ballet, Brooklyn Flavor". The New York Times. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

Zoepf, Katherine (2003). "Urban Tactics: Bolshoi To Brooklyn, In a Bound". The New York Times. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

Shelby, Joyce (2002). "Ballet School Excels at Language of Dance". Daily News. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

Rush, Alex (December 12, 2010). "Brighton Ballet Theater's version of Tchaikovsky classic is no hard 'Nut'". Nypost.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "Home". mastertheater.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "NYPD - Precincts". Nyc.gov. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "Police Department : City of New York : CompStat" (PDF). Nyc.gov. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ Raab, Selwyn (1994). "Influx of Russian Gangsters Troubles F.B.I. in Brooklyn". The New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ Keteyian, Armen (2008). "Undercover Look Inside The Russian Mob". CBS News (online, May 13). Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ Orleck, Annelise; Cooke, Elizabeth (1999). The Soviet Jewish Americans. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 9780313300745.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

^ "Reputed Russian crime chief arrested". The New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

^ "Brooklyn Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. November 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

^ "Directions - P.S. K225 - The Eileen E. Zaglin - K225 - New York City Department of Education". schools.nyc.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

^ Rich, Motoko (2009). "In Web Age, Library Job Gets Update". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

^ "Directions - P.S. 253 - K253 - New York City Department of Education". schools.nyc.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

^ Fertig, Beth (2012). "Test Driving a Pilot Teacher Evaluation System". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.Ms. Moloney has been testing a new framework for evaluating teachers this year at the school, which is actually in Brighton Beach...

^ "The Magnet School of Media Arts & Communication". nyc.gov. July 22, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ abc Scharfenberg, David (2006). "Safety Belts On? Renewal Has Its Hazards". The New York Times. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "Map of Brighton Beach environs" (JPG). Graphics8.nytimes.com. Retrieved November 11, 2015.Coney Island, which has a residential population of about 53,000, is bounded by the Belt Parkway to the north, Ocean Parkway to the east and the Atlantic Ocean to the south.

^ Hughes, C. J. (2010). "Waterfront Living That Doesn't Break the Bank". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

^ ab "Welcome To I.S. 303 Academy for Career Exploration - I.S. 303 Herbert S. Eisenberg - K303 - New York City Department of Education". schools.nyc.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

^ "Student, 17, Is Shot in Brighton Beach". The New York Times. 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

^ "Welcome". nyc.gov. July 23, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "Directions - Rachel Carson High School for Coastal Studies - K344 - New York City Department of Education". schools.nyc.gov. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

^ [2][dead link]

^ "Brighton Beach Library". brooklynpubliclibrary.org. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ Gaidai, Leonid (October 8, 2015). "There's Good Weather on Deribasovskaya, It's Raining Again in Brighton Beach (Na Deribasovskoi khoroshaia pogoda, ili Na Braiton bich opiat' idut dozhdi, 1992)". KinoKultura. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

^ Ebert, Roger. "Little Odessa Movie Review & Film Summary (1995) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (September 14, 1996). "Double the Fun? Or Just the Bodies?". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

^ Mitchell, Elvis. "FILM REVIEW; Addicted to Drugs and Drug Rituals", The New York Times, October 6, 2000. Accessed February 26, 2017. "It's never clear when the movie is set, but its Brighton Beach isn't pretty."

^ Fairbanks, Amanda M. "Brighton Beach, N.J.", The New York Times, February 27, 2009. Accessed February 26, 2017. "IN scene after scene in Two Lovers, the new movie starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Joaquin Phoenix as a star-crossed couple, the Brooklyn neighborhood of Brighton Beach is on lush display."

^ Swartzfell, Griffin. "Netflix Picks: Lords of War", Colorado Springs Independent, August 23, 2015. Accessed January 19, 2018. "Lord of War is the tale of the American dream gone as wrong as possible. Yuri Orlov (Cage) and his family fled the Ukraine for Brighton Beach."

^ "Vector by Robin Cook", Kirkus Reviews. Accessed February 26, 2017. "An anti-Semite, Yuri feels dismissed as a human being by American Zionists and has set up a bioweapons lab in his basement in Brighton Beach, undertaking what he calls Operation Revenge."

^ "Lifetime TV Shows - myLifetime.com". myLifetime.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

^ "Eddie Daniels"[permanent dead link], National Public Radio. Accessed February 26, 2017. "Clarinetist Eddie Daniels was born in 1941 and raised in the Brighton Beach neighborhood of Brookly, New York, NY."

^ Berger, Joseph (2004). "Vintage Pop Star With the Soul of a Bar Mitzvah Boy". The New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2009.Several years before enrolling in Juilliard, he had been introduced to a neighbor with a touch of the poet, Howard Greenfield, and they became a songwriting team for the next 20 years.

^ Zaklikowski, Dovid. "Rabbi David B. Hollander, Defender of Jewish Faith and Practice, Passes Away", Chabad, February 18, 2009. Accessed February 26, 2017. "Hollander remained at the Mount Eden Jewish Center until its closing in 1980 due to the migration of Jews to other areas of the city. His next pulpit, which he held until his passing, was at the Hebrew Alliance Congregation in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn."

^ "Lea Bayers Rapp". Archived from the original on December 6, 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

^ McFadden, Robert D. (June 16, 1986). "Link is Sought After Slaying of 2d Russian". New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

^ "Broadway World". Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

^ Dettelbach, Cynthia (2004). "From angst-ridden teenager to world-class music star". Cleveland Jewish News. Retrieved September 23, 2009.That includes instant face and name recognition, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, a place in the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and even a street named after him in his native Brighton Beach, Brooklyn.

^ "The Tokens - Inductees - The Vocal Group Hall of Fame Foundation". vocalgroup.org. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

Further reading

Coney Island History: The Rise and Fall of Engeman's Brighton Beach Resort at Heart of Coney Island

Weinstein, Stephen (2000). "Brighton Beach". In Jackson, Kenneth T.; Keller, Lisa; Flood, Nancy. The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New York, NY, and New Haven, CT, USA: The New York Historical Society and Yale University Press. pp. 139–140. ISBN 0300114656. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

Williams, Keith (2012). "Brighton Beach: Old World mentality, New World reality". The Weekly Nabe (online, July 29). Retrieved July 29, 2012.

External links

Brooklyn/Coney Island and Brighton Beach travel guide from Wikivoyage

Brooklyn/Coney Island and Brighton Beach travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Brighton Beach, Brooklyn at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brighton Beach, Brooklyn at Wikimedia Commons