Balaklava

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP Balaklava Балаклава Balıqlava | |||

|---|---|---|---|

part of Sevastopol | |||

| |||

Balaklava Location of Balaklava within Sevastopol. | |||

Coordinates: 44°30′0″N 33°36′0″E / 44.50000°N 33.60000°E / 44.50000; 33.60000Coordinates: 44°30′0″N 33°36′0″E / 44.50000°N 33.60000°E / 44.50000; 33.60000 | |||

| Country | Disputed | ||

| Region | Sevastopol | ||

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) | ||

| Population | |||

| • Total | 18,649 | ||

| Time zone | MSK (UTC+4) | ||

| Postal code | 299xxx | ||

| Area code(s) | +380-692 | ||

| Former name | Cembalo (until 1475), Yamboli, Symbolon | ||

| Website | http://balaklava.crimea.ua/ | ||

Balaklava (Ukrainian: Балаклáва, Russian: Балаклáва, Crimean Tatar: Balıqlava, Greek: Σύμβολον) is a former city on the Crimean Peninsula and part of the city of Sevastopol. It was a city in its own right until 1957 when it was formally incorporated into the municipal borders of Sevastopol by the Soviet government. It also is an administrative center of Balaklava Raion that used to be part of the Crimean Oblast before it was transferred to Sevastopol Municipality. Population: 18,649 (2014 Census).[1]

Contents

1 History

2 Underground submarine base

3 See also

4 Notes

5 External links

History

Balaklava harbor, 1830

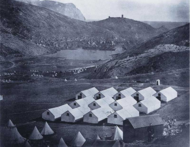

Balaklava harbor, 1855, photographed by Roger Fenton

Balaklava has changed possession several times during its history. A settlement at its present location was founded under the name of Symbolon (Σύμβολον) by the Ancient Greeks, for whom it was an important commercial city.

During the Middle Ages, it was controlled by the Byzantine Empire and then by the Genoese who conquered it in 1365. The Byzantines called the town Yamboli and the Genoese named it Cembalo. The Genoese built a large trading empire in both the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, buying slaves in Eastern Europe and shipping them to Egypt via the Crimea, a lucrative market hotly contested with by the Venetians.

The ruins of a Genoese fortress positioned high on a clifftop above the entrance to the Balaklava Inlet are a popular tourist attraction and have recently become the stage for a Medieval festival. The fortress is a subject of Mickiewicz's penultimate poem in his 1826 cycle of Crimean Sonnets.

In 1475 Cembalo City was conquered by Turks and they rename it to Balyk-Yuva (Fish's Nest) which subsequently became Balaklava.[2]

During the Russo-Turkish War, 1768-1774, the Russian troops invaded Crimea in 1771. Thirteen years later, Crimea was definitively annexed by the Russian Empire. After that, Crimean Tatar and Turkish population was forcefully replaced by Greek Orthodox people from the Archipelago.[citation needed]

In 1787 the city was visited by Catherine the Great.[3]

The town became famous for the Battle of Balaclava during the Crimean War thanks to the suicidal Charge of the Light Brigade, a British cavalry charge due to a misunderstanding sent up a valley strongly held on three sides by the Russians, in which about 250 men were killed or wounded, and over 400 horses lost, effectively reducing the size of the mounted brigade by two thirds and destroying some of the finest light cavalry in the world to no military purpose.[4] The British poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson immortalized the battle in verse in his Charge of the Light Brigade.

The balaclava, a tight knitted garment covering the whole head and neck with holes for the eyes and mouth, also takes its name from this settlement, where soldiers first wore them. Also numerous towns founded in English-speaking countries in later parts of the 19th Century were named "Balaklava" (see Balaklava (disambiguation)).

During the Second World War, Balaklava was the southernmost point in the Soviet-German lines.[citation needed]

In 1954 Balaklava, together with the whole Crimea, passed from Russia to Ukraine. It became part of the independent state of Ukraine in 1991. Today there are over 50 monuments in the town dedicated to the remembrance of military valour in past wars, including the Great Patriotic War, the Crimean War and the Russian Civil War.[citation needed]

In 2014, due to the 2014 Crimean crisis, Balaklava, along with the rest of the Crimea, was annexed by Russian Federation.

Underground submarine base

One of the monuments is an underground, formerly classified submarine base that was operational until 1993. The base was said to be virtually indestructible and designed to survive a direct atomic impact. During that period, Balaklava was one of the most secret residential areas in the Soviet Union. Almost the entire population of Balaklava at one time worked at the base; even family members could not visit the town of Balaklava without a good reason and proper identification. The base remained operational after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 until 1993 when the decommissioning process started. This process saw the removal of the warheads and low-yield torpedoes. In 1996, the last Russian submarine left the base. The base has since been opened to the public as the Naval museum complex Balaklava.

Army camp at Balaklava during the Crimean War

Modern Balaklava - view from the Genoese fortress

Entrance to submarine Soviet navy base

Tunnel

See also

Cape Aya – a headland near Balaklava known for its scenic grottoes- Great Storm of 1854

- Hicks Withers-Lancashire

Notes

^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2014). "Таблица 1.3. Численность населения Крымского федерального округа, городских округов, муниципальных районов, городских и сельских поселений" [Table 1.3. Population of Crimean Federal District, Its Urban Okrugs, Municipal Districts, Urban and Rural Settlements]. Федеральное статистическое наблюдение «Перепись населения в Крымском федеральном округе». ("Population Census in Crimean Federal District" Federal Statistical Examination) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

^ Sergei R. Grinevetsky, et. al. ” The Black Sea Encyclopedia”, Springer, 2014: 80-81.

^ Some rural communities surrounding Balaklava remained populated by Crimean Tatars until their deportation in 1944.[citation needed]

^ Brighton, Terry, Hell Riders: The Truth about the Charge of the Light Brigade. London: Penguin, 2005. New York: Henry Holt, 2005.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Balaklava. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balaklava. |

(in English) Balaklava and the Sevastopol Inquiry, 1855, by Commander W.Gordon, R.N.

(in English) Balaklava Photoalbum

(in Russian) Genoese fortress in Balaklava

(in English) Russian underground Submarine Base Englishrussia.com (photos)

(in English) Russian underground Submarine Base Iconicarchive.ch (iconicarchive gallery)

(in Russian) Panorams of Balaklava

(in English) Photos of underground Submarine Base