Armistice of Cassibile

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

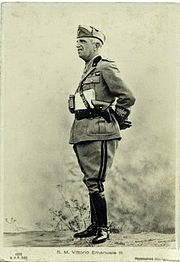

King Victor Emmanuel III in his uniform as Marshal of Italy.

The Armistice of Cassibile[1] was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 by Walter Bedell Smith and Giuseppe Castellano, and made public on 8 September, between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was signed at a conference of generals from both sides in an Allied military camp at Cassibile in Sicily, which had recently been occupied by the Allies. The armistice was approved by both King Victor Emmanuel III and Italian Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio. The armistice stipulated the surrender of Italy to the Allies.

After its publication, Germany retaliated against Italy, attacking Italian forces in Italy, South of France and the Balkans. Italian forces were quickly defeated and most of Italy was occupied by German troops, while the King, the government and most of the navy reached territories occupied by the Allies.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Towards the signing

2 Treaty

2.1 Conditions

2.2 The way to the signing

3 Aftermath

4 Italian Navy

5 See also

6 Notes

7 References

8 External links

Background

Following the surrender of the Axis powers in North Africa on 13 May 1943, the Allies bombed Rome first on 16 May, invaded Sicily on 10 July and were preparing to land on the Italian mainland.

In the spring of 1943, preoccupied by the disastrous situation of the Italian military in the war, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini removed several figures from the government whom he considered to be more loyal to King Victor Emmanuel III than to the Fascist regime. These moves by Mussolini were described[by whom?] as slightly hostile acts to the king, who had been growing increasingly critical of the war.

To help carry out his plan[clarification needed], the King asked for the assistance of Dino Grandi. Grandi was one of the leading members of the Fascist hierarchy and, in his younger years, he had been considered to be the sole credible alternative to Mussolini as leader of the National Fascist Party. The King was also motivated by the suspicion that Grandi's ideas about Fascism might be changed abruptly. Various ambassadors, including Pietro Badoglio himself, proposed to him the vague possibility of succeeding Mussolini as dictator.

The secret frondeur later involved Giuseppe Bottai, another high member of the Fascist directorate and Minister of Culture, and Galeazzo Ciano, probably the second most powerful man in the Fascist party and Mussolini's son-in-law. The conspirators devised an Order of the Day for the next reunion of the Grand Council of Fascism (Gran Consiglio del Fascismo) which contained a proposal to restore direct control of politics to the king. Following the Council, held on 23 July 1943, where the "order of the day" was adopted by majority vote, Mussolini was summoned to meet the King and dismissed as Prime Minister. Upon leaving the meeting, Mussolini was arrested by carabinieri and spirited off to the island of Ponza. Badoglio took the position of Prime Minister. This went against what had been promised to Grandi, who had been told that another general of greater personal and professional qualities (Enrico Caviglia) would have taken the place of Mussolini.

The appointment of Badoglio apparently did not change the position of Italy as Germany's ally in the war. However, many channels were being probed to seek a peace treaty with the Allies. Meanwhile, Hitler sent several divisions south of the Alps, officially to help defend Italy from allied landings but in reality to control the country.

Towards the signing

General Giuseppe Castellano

Three Italian generals (including Giuseppe Castellano) were separately sent to Lisbon in order to contact Allied diplomats. However, to start out the proceedings the Allies had to solve a problem concerning who was the most authoritative envoy: the three generals had in fact soon started to quarrel about the question of who enjoyed the highest authority. In the end, Castellano was admitted to speak with the Allies in order to set the conditions for the surrender of Italy. Among the representatives of the Allies, there was the British ambassador to Portugal, Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell, and two generals sent by Dwight D. Eisenhower, the American Walter Bedell Smith (Eisenhower's Chief of Staff) and the British Kenneth Strong (Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence).

On 27 August Castellano returned to Italy and, three days later, briefed Badoglio about the Allied request for a meeting to be held in Sicily, which had been suggested by the British ambassador to the Vatican.

To ease communication between the Allies and the Italian Government, a captured British SOE agent, Dick Mallaby, was released from Verona prison and secretly moved to the Quirinale. It was vital that the Germans remained ignorant of any suggestion of Italian surrender and the SOE was seen as the most secure method in the circumstances.[2]

Treaty

Conditions

Badoglio still considered it possible to gain favourable conditions in exchange for the surrender. He ordered Castellano to insist that any surrender of Italy was subordinate to a landing of Allied troops on the Italian mainland (the Allies at this point were holding only Sicily and some minor islands).

On 31 August General Castellano reached Termini Imerese, in Sicily, by plane and was subsequently transferred to Cassibile, a small town in the neighbourhood of Syracuse. It soon became obvious that the two sides in the negotiations had adopted rather distant positions. Castellano pressed the request that the Italian territory be defended from the inevitable reaction of the German Wehrmacht against Italy after the signing. In return, he received only vague promises, which included the launching of a Parachute division over Rome. Moreover, these actions were to be conducted contemporaneously with the signing and not preceding it, as the Italians had wanted.

The following day Castellano was received by Badoglio and his entourage. The Minister of Foreign Affairs Baron Raffaele Guariglia declared that the Allied conditions were to be accepted. Other generals like Giacomo Carboni maintained however that the Army Corps deployed around Rome was insufficient to protect the city, due to lack of fuel and ammunition, and that the armistice had to be postponed. Badoglio did not pronounce himself in the meeting. In the afternoon he appeared before the King, who decided to accept the armistice conditions.

The way to the signing

A confirmation telegram was sent to the Allies. The message, however, was intercepted by the German armed forces, which had long since begun to suspect that Italy was seeking a separate armistice. The Germans contacted Badoglio, who repeatedly confirmed the unwavering loyalty of Italy to its German ally. His reassurances were doubted by the Germans, and the Wehrmacht started to devise an effective plan (Operation Achse) to take control of Italy as soon as the Italian government had switched allegiance to the Allies.

On 2 September Castellano set off again to Cassibile with an order to confirm the acceptance of the Allied conditions. He had no written authorisation from the head of the Italian Government, Badoglio, who wanted to dissociate himself as much as possible from the forthcoming defeat of his country.

The signing ceremony began at 14:00 on 3 September. Castellano and Bedell Smith signed the accepted text on behalf of respectively Badoglio and Eisenhower. A bombing mission on Rome by five hundred airplanes was stopped at the last moment: it had been Eisenhower's deterrent to accelerate the procedure of the armistice. Harold Macmillan, the British government's representative minister at the Allied Staff, informed Winston Churchill that the armistice had been signed "without amendments of any kind".

Aftermath

Only after the signing had taken place was Castellano informed of the additional clauses that had been presented by General Campbell to another Italian general, Zanussi, who had also been in Cassibile since 31 August. Zanussi, for unclear reasons, had not informed Castellano about them. Bedell Smith, nevertheless, explained to Castellano that the further conditions were to have taken effect only if Italy had not taken on a fighting role in the war alongside the Allies.

On the afternoon of the same day, Badoglio had a briefing with the Italian Ministers of Navy, Air Forces and War, and with the King's representatives as well. However, he omitted any mention of the signing of the armistice, referring only to ongoing negotiations.

The day of entry into force of the armistice was linked to a planned landing in Central Italy and was left to Allied discretion. Castellano still understood the date intended to be 12 September and Badoglio started to move troops to Rome.

On 7 September, a small Allied delegation reached Rome to inform Badoglio that the next day would have been the day of the armistice. He was also informed about the pending arrival of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division into airports around the city. Badoglio told this delegation that his army was not ready to support this landing and that most airports in the area were under German control; he asked for a deferral of the armistice of a few days. When General Eisenhower learned of this, the landing in Rome of American troops was cancelled, but the day of the armistice was confirmed since other troops were already en route by sea to land on southern Italy.

When the armistice was announced by Allied radio, on the afternoon of 8 September, German forces immediately attacked Italian forces by executing Operation Achse; the majority of the Italian Army had not been informed about the armistice and no clear orders had been issued about the line of conduct to be taken in the face of the German armed forces. Some of the Italian divisions that should have defended Rome were still in transit from the south of France. The King, along with the royal family and Badoglio, fled Rome on the early morning of the 9th, taking shelter in Brindisi, in the south of the country. The initial intention had been to move army headquarters out of Rome together with the King and the prime minister, but few staff officers reached Brindisi. In the meanwhile the Italian troops, without instructions, collapsed and were soon overwhelmed, and some small units decided to stay loyal to the German ally. Between 8 and 12 September, German forces therefore occupied all of the Italian territory still not under Allied control except Sardinia and part of Apulia, without meeting great organized resistance. In Rome, an Italian governor, with the support of an Italian infantry division, nominally ruled the city until 23 September but in practice, the city was under German control from 11 September.

On 3 September, British and Canadian troops had crossed the Strait of Messina and begun landing in the southernmost tip of Calabria in Operation Baytown. The day after the armistice was made public, 9 September, the Allies made landings at Salerno and at Taranto.

The Allies failed to take full advantage of the Italian armistice and they were quickly checked by German troops. In terrain that favoured defence, it took 20 months for the Allied forces to reach the northern borders of Italy.

Some of the Italian troops based outside of Italy, in the occupied Balkans and Greek islands, were able to stand some weeks after the armistice but without any determined support by the Allies, they were all overwhelmed by the Germans by the end of September 1943. On the island of Cephalonia, the Italian Acqui Division was massacred after resisting German forces. Only on the islands of Leros and Samos, with British reinforcements, did the resistance last until November 1943, and in Corsica Italian troops forced German troops to leave the island.

In other cases individual Italian units of various size stayed on the Axis side. Many of these units formed the nucleus of the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic[citation needed].

While Italy's army and air force virtually disintegrated with the announcement of the armistice on 8 September, the Allies coveted the country's navy with 206 ships in total, including the battleships Roma, Vittorio Veneto and Italia (known as the Littorio until July 1943).[3] There was a danger that some of the Italian Navy might fight on, be scuttled or, of more concern for the Allies, end up in German hands.[3] As such, the truce called for Italian warships on Italy's west coast, mostly located at La Spezia and Genoa, to sail for North Africa (passing Corsica and Sardinia); and for those at Taranto, in the heel of Italy, to sail for Malta.[3]

At 02:30, on 9 September, the three battleships Roma, Vittorio Veneto and Italia, "shoved off from La Spezia escorted by three light cruisers and eight destroyers".[3] When German troops who had stormed into the town to prevent the defection became enraged by these ships' escape, "they rounded up and summarily shot several Italian captains who, unable to get their vessels under way, had scuttled them".[3] That afternoon German bombers attacked the ships, sailing without air cover, off Sardinia, launching guided bombs; several ships suffered damage and Roma sank with the loss of nearly 1,400 men.[3] Most of the remaining ships made it safely to North Africa, "while three destroyers and a cruiser which had stopped to rescue survivors, docked in Menorca."[3] The Italian navy's turnover proceeded more smoothly in other areas of Italy. When an Allied naval force headed for the big naval base of Taranto, they watched a flotilla of Italian ships sailing out of Taranto harbour towards surrender at Malta.[3]

An agreement between the Allies and the Italians in late September provided for some of the Italian Navy to be kept in commission, but the battleships were to be reduced to care and maintenance, effectively disarmed. Italian mercantile marine vessels were to operate under the same general conditions as those of the Allies. In all cases, the Italian vessels would retain their Italian crews and fly Italian flags.[4]

See also

- Military history of Italy during World War II

- Allied invasion of Italy

- European Theatre of World War II

- Italian Co-Belligerent Army

- Operation Panzerfaust

- King Michael's Coup

- Bulgarian coup d'état of 1944

- Moscow Armistice

- Italian Army in Russia

- Badoglio Proclamation

- Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947

Notes

^ Howard McGaw Smyth, "The Armistice of Cassibile", Military Affairs 12:1 (1948), 12–35.

^ Marks, Leo (1998). Between Silk and Cyanide. London: HarperCollins. chapter 47. ISBN 0-00-255944-7.

^ abcdefgh Robert Wallace & the editors of Time-Life Books, The Italian Campaign, Time-Life Books Inc, 1978. p.57

^ Armistice with Italy: Employment and Disposition of Italian Fleet and Merchant Marine (Cunningham-de Courten Agreement) 23 September 1943

References

Aga Rossi, Elena (1993). Una nazione allo sbando (in Italian). Bologna.

Bianchi, Gianfranco (1963). 25 luglio, crollo di un regime (in Italian). Milan.

Marchesi, Luigi (1969). Come siamo arrivati a Brindisi (in Italian). Milan.

External links

(in Italian) Il diario del generale Giuseppe Castellano, La Sicilia, 8 settembre 2003

(in Italian) 8 Settembre 1943, l'armistizio Centro Studi della Resistenza dell'Anpi di Roma- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: Terms of the Armistice with Italy; September 3, 1943