William Jennings Bryan

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

William Jennings Bryan | |

|---|---|

| |

| 41st United States Secretary of State | |

In office March 5, 1913 – June 9, 1915 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Philander C. Knox |

| Succeeded by | Robert Lansing |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Nebraska's 1st district | |

In office March 4, 1891 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | William James Connell |

| Succeeded by | Jesse Burr Strode |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1860-03-19)March 19, 1860 Salem, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1925(1925-07-26) (aged 65) Dayton, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Baird Bryan (m. 1884–1925) |

| Children | 3, including Ruth |

| Education | Illinois College (BA) Northwestern University (LLB) |

| Signature | |

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American orator and politician from Nebraska. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, standing three times as the party's nominee for President of the United States. He also served in the United States House of Representatives and as the United States Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson. Just before his death he gained national attention for attacking the teaching of evolution in the Scopes Trial. Because of his faith in the wisdom of the common people, he was often called "The Great Commoner".[1]

Born and raised in Illinois, Bryan moved to Nebraska in the 1880s. He won election to the House of Representatives in the 1890 elections, serving two terms before making an unsuccessful run for the Senate in 1894. At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Bryan delivered his "Cross of Gold speech" which attacked the gold standard and the eastern moneyed interests and crusaded for inflationary policies built around the expanded coinage of silver coins. In a repudiation of incumbent President Grover Cleveland and his conservative Bourbon Democrats, the Democratic convention nominated Bryan for president, making Bryan the youngest major party presidential nominee in U.S. history. Subsequently, Bryan was also nominated for president by the left-wing Populist Party, and many Populists would eventually follow Bryan into the Democratic Party. In the intensely fought 1896 presidential election, Republican nominee William McKinley emerged triumphant. Bryan gained fame as an orator as he invented the national stumping tour when he reached an audience of 5 million people in 27 states in 1896.

Bryan retained control of the Democratic Party and won the presidential nomination again in 1900. In the aftermath of the Spanish–American War, Bryan became a fierce opponent of American imperialism, and much of the campaign centered on that issue. In the election, McKinley again defeated Bryan, winning several Western states that Bryan had won in 1896. Bryan's influence in the party weakened after the 1900 election, and the Democrats nominated the conservative Alton B. Parker in the 1904 presidential election. Bryan regained his stature in the party after Parker's resounding defeat by Theodore Roosevelt, and voters from both parties increasingly embraced the progressive reforms that had long been championed by Bryan. Bryan won his party's nomination in the 1908 presidential election, but he was defeated by Roosevelt's chosen successor, William Howard Taft. Along with Henry Clay, Bryan is one of the two individuals since 1804 who received electoral votes in three separate presidential elections but never won a presidential election. The 493 cumulative electoral votes cast for Bryan in those three elections are the most received by a presidential candidate never elected.

After the Democrats won the presidency in the 1912 election, Woodrow Wilson rewarded Bryan's support with the important cabinet position of Secretary of State. Bryan helped Wilson pass several progressive reforms through Congress, but he and Wilson clashed over U.S. neutrality in World War I. Bryan resigned from his post in 1915 after Wilson sent Germany a note of protest in response to the sinking of Lusitania by a German U-boat. After leaving office, Bryan retained some of his influence within the Democratic Party, but he increasingly devoted himself to religious matters and anti-evolution activism. He opposed Darwinism on religious and humanitarian grounds, most famously in the 1925 Scopes Trial. Since his death in 1925, Bryan has elicited mixed reactions from various commentators, but he is widely considered to have been one of the most influential figures of the Progressive Era.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Early political career

2.1 Congressional service

3 Presidential candidate and party leader

3.1 Presidential election of 1896

3.1.1 Democratic nomination

3.1.2 General election

3.2 War and peace: 1898–1900

3.2.1 Spanish–American War

3.2.2 Presidential election of 1900

3.3 Between presidential campaigns, 1901–1907

3.4 Presidential election of 1908

4 Wilson presidency

4.1 1912 election

4.2 Secretary of State

5 Later career

5.1 Political involvement

5.2 Florida real estate promoter

5.3 Anti-evolution activism

5.3.1 Scopes Trial

6 Death

7 Family

8 Legacy

8.1 Historical reputation and political legacy

8.2 In popular culture

8.3 Memorials

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

11.1 Works cited

12 Further reading

12.1 Biographies

12.2 Specialized studies

12.3 Writings by Bryan

13 External links

Early life and education

Bryan's birthplace in Salem, Illinois

Attorney Mary Baird Bryan, the wife of William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was born in Salem, Illinois, on March 19, 1860, to Silas Lillard Bryan and Mariah Elizabeth (Jennings) Bryan.[2] Silas Bryan had been born in 1822, and had established a legal practice in Salem in 1851. He married Mariah, a former student of his at McKendree College, in 1852.[3] Of Scots-Irish and English ancestry,[a] Silas Bryan was an avid Jacksonian Democrat. He won election as a state circuit judge, and in 1866 moved his family to a 520-acre (210.4 ha) farm north of Salem, living in a ten-room house that was the envy of Marion County.[5] Silas served in various local positions and sought election to Congress in 1872, but was narrowly defeated by the Republican candidate.[6] An admirer of Andrew Jackson and Stephen A. Douglas, Silas passed on his Democratic affiliation to his son, William, who would remain a life-long Democrat.[7]

Bryan was the fourth child of Silas and Mariah, but all three of his older siblings died during infancy. Bryan also had five younger siblings, four of whom lived to adulthood.[8] Bryan was home-schooled by his mother until the age of ten. Silas was a Baptist and Mariah was a Methodist, but Bryan's parents allowed him to choose his own church. At age fourteen, Bryan had a conversion experience at a revival. He said it was the most important day of his life.[9] Bryan also devoted himself to oratory, giving public speeches as early as the age of four.[10] At age fifteen, Bryan was sent to attend Whipple Academy, a private school in Jacksonville, Illinois.[11]

A young Bryan

After graduating from Whipple Academy, Bryan entered Illinois College, which was also located in Jacksonville. During his time at Illinois College, Bryan served as chaplain of the Sigma Pi literary society.[12] He also continued to hone his public speaking skills, taking part in numerous debates and oratorical contests.[13] In 1879, while still in college, Bryan met Mary Elizabeth Baird, the daughter of an owner of a nearby general store, and began courting her.[14] Bryan and Mary Elizabeth married on October 1, 1884.[15] Mary Elizabeth would emerge as an important part of Bryan's career, managing his correspondence and helping him prepare speeches and articles.[14]

After graduating from college at the top of his class,[12] Bryan studied law at Union Law College (which later became Northwestern University School of Law) in Chicago.[16] While attending law school, Bryan worked for attorney Lyman Trumbull, a former senator and friend of Silas Bryan's who would serve as an important political ally to the younger Bryan until his death in 1896.[17] After graduating from law school, Bryan returned to Jacksonville to take a position with a local law firm. Frustrated by the lack of political and economic opportunities in Jacksonville, in 1887 Bryan and his wife moved west to Lincoln, the capital of the fast-growing state of Nebraska.[18]

Early political career

Congressional service

Bryan established a successful legal practice in Lincoln with partner Adolphus Talbot, a Republican whom Bryan had known in law school.[19] Bryan also entered local politics, campaigning on behalf of Democrats like Julius Sterling Morton and Grover Cleveland.[20] After earning notoriety for his effective speeches in 1888, Bryan ran for Congress in the 1890 election.[21] Bryan called for a reduction in tariff rates, the coinage of silver at a ratio equal to that of gold, and action to stem the power of trusts. In part due to a series of strong debate performances, Bryan defeated incumbent Republican Congressman William James Connell, who campaigned on the orthodox Republican platform centered around the protective tariff.[22] Bryan's victory made him only the second Democrat to represent Nebraska in Congress.[23] Nationwide, Democrats picked up seventy-six seats in the House, giving the party a majority in that chamber. The Populist Party, a third party that drew support from agrarian voters in the West, also picked up several seats in Congress.[24]

With the help of Congressman William McKendree Springer, Bryan secured a coveted spot on the House Ways and Means Committee. He quickly earned a reputation as a talented orator, and he set out to gain a strong understanding of the key economic issues of the day.[25] During the Gilded Age, the Democratic Party had begun to separate into two groups. The conservative northern "Bourbon Democrats," along with some allies in the South, sought to limit the size and power of the federal government. Another group of Democrats, drawings its membership largely from the agrarian movements of the South and West, favored greater federal intervention in order to help farmers, regulate railroads, and limit the power of large corporations.[26] Bryan became affiliated with the latter group, advocating for the free coinage of silver ("free silver") and the establishment of a progressive federal income tax. Though it endeared him to many reformers, Bryan's call for free silver cost him the support of Morton and some other conservative Nebraska Democrats.[27] Free silver advocates were opposed by banks and bond holders who feared the effects of inflation.[28]

Bryan sought re-election in 1892 with the support of many Populists, and he backed Populist presidential candidate James B. Weaver instead of the Democratic presidential candidate, Grover Cleveland. Bryan won re-election by just 140 votes, while Cleveland defeated Weaver and incumbent Republican President Benjamin Harrison in the 1892 presidential election. Cleveland appointed a cabinet consisting largely of conservative Democrats like Morton, who became Cleveland's secretary of agriculture. Shortly after Cleveland took office, a series of bank closures brought on the Panic of 1893, a major economic crisis. In response, Cleveland called a special session of Congress with the intention of repealing the 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which required the federal government to purchase several million ounces of silver every month. Though Bryan mounted a campaign to save the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, a coalition of Republicans and Democrats successfully repealed it.[29] Bryan was, however, successful in passing an amendment that provided for the establishment of the first peacetime federal income tax.[30][b]

As the economy declined after 1893, the reforms favored by Bryan and the Populists became more popular among many voters. Rather than running for re-election in 1894, Bryan sought election to the United States Senate. He also became the editor-in-chief of the Omaha World-Herald, although most editorial duties were performed by Richard Lee Metcalfe and Gilbert Hitchcock. Nationwide, the Republican Party won a huge victory in the elections of 1894, gaining over 120 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. In Nebraska, despite Bryan's popularity, the Republicans elected a majority of the state legislators, and Bryan lost the senate election to Republican John Mellen Thurston.[c] Bryan was nonetheless pleased with the result of the 1894 election, as the Cleveland wing of the Democratic Party had been discredited and Bryan's preferred gubernatorial candidate, Silas A. Holcomb, had been elected by a coalition of Democrats and Populists.[31]

After the 1894 elections, Bryan engaged in a nationwide speaking tour designed to boost free silver, move his party away from the conservative policies of the Cleveland administration, lure Populists and free silver Republicans into the Democratic Party, and raise Bryan's public profile in advance of the next election. Speaking fees allowed Bryan to give up his legal practice and devote himself full-time to oratory.[32]

Presidential candidate and party leader

Presidential election of 1896

Democratic nomination

.mw-parser-output .quoteboxbackground-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleftmargin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatrightmargin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centeredmargin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright pfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .quotebox-titlebackground-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:beforefont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:afterfont-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-alignedtext-align:left.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-alignedtext-align:right.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-alignedtext-align:center.mw-parser-output .quotebox citedisplay:block;font-style:normal@media screen and (max-width:360px).mw-parser-output .quoteboxmin-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important

By 1896, free silver forces were ascendant within the party. Though many Democratic leaders were not as enthusiastic about free silver as Bryan was, most recognized the need to distance the party from the unpopular policies of the Cleveland administration. By the start of the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Congressman Richard P. Bland, a long-time champion of free silver, was widely perceived to be the front-runner for the party's presidential nomination. Bryan hoped to offer himself as a presidential candidate, but his youth and relative inexperience gave him a lower profile than veteran Democrats like Bland, Governor Horace Boies of Iowa, and Vice President Adlai Stevenson. The free silver forces quickly established dominance over the convention, and Bryan helped draft a party platform that repudiated Cleveland, attacked the conservative rulings of the Supreme Court, and called the gold standard "not only un-American but anti-American."[34]

Conservative Democrats demanded a debate on the party platform, and on the third day of the convention each side put forth speakers to debate free silver and the gold standard. Bryan and Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina were chosen as the speakers who would advocate on behalf of free silver, but Tillman's speech was poorly received by delegates from outside the South due to its sectionalism and references to the Civil War. Charged with delivering the convention's last speech on the topic of monetary policy, Bryan seized his opportunity to emerge as the nation's leading Democrat. In his "Cross of Gold" speech, Bryan argued that the debate over monetary policy was part of a broader struggle for democracy, political independence, and the welfare of the "common man." Bryan's speech was met with rapturous applause and a celebration on the floor of the convention that lasted for over half an hour.[35]

Bryan campaigning for president, October 1896

The following day, the Democratic Party held its presidential ballot. With the continuing support of Governor John Altgeld of Illinois, Bland led the first ballot of the convention, but he fell far short of the necessary two-thirds majority of delegates. Bryan finished in a distant second on the convention's first ballot, but his Cross of Gold speech had left a strong impression on many delegates. Despite the distrust of party leaders like Altgeld, who was wary of supporting an untested candidate, Bryan's strength grew over the next four ballots. He gained the lead on the fourth ballot and won his party's presidential nomination on the fifth ballot.[36] At the age of 36, Bryan became (and still remains) the youngest presidential nominee of a major party in American history.[37] The convention nominated Arthur Sewall, a wealthy Maine shipbuilder who also favored free silver and the income tax, as Bryan's running mate.[36]

General election

Conservative Democrats known as the "Gold Democrats" nominated a separate ticket. Cleveland himself did not publicly attack Bryan, but privately he favored the Republican candidate, William McKinley, over Bryan. Many urban newspapers in the Northeast and Midwest that had supported previous Democratic tickets also opposed Bryan's candidacy.[38] Bryan did, however, win the support of the Populist Party, which nominated a ticket consisting of Bryan and Thomas E. Watson of Georgia. Though Populist leaders feared that the nomination of the Democratic candidate would damage the party in the long-term, they shared many of Bryan's political views and had developed a productive working relationship with Bryan.[39]

The Republican campaign painted McKinley as the "advance agent of prosperity" and social harmony, and warned of the supposed dangers of electing Bryan. McKinley and his campaign manager, Mark Hanna, knew that McKinley could not match Bryan's oratorical skills. Rather than giving speeches on the campaign trail, the Republican nominee conducted a front porch campaign. Hanna, meanwhile, raised an unprecedented amount of money, dispatched campaign surrogates, and organized the distribution of millions of pieces of campaign literature.[40]

1896 electoral vote results

Facing a huge campaign finance disadvantage, the Democratic campaign relied largely on Bryan's oratorical skills. Breaking with the precedent set by most major party nominees, Bryan gave some 600 speeches, primarily in the hotly contested Midwest.[41] Bryan invented the national stumping tour, reaching an audience of 5 million in 27 states.[42] He was building a coalition of the white South, poor northern farmers and industrial workers, and silver miners against banks and railroads and the "money power". Free silver appealed to farmers who would be paid more for their products but not to industrial workers who would not get higher wages but would pay higher prices. The industrial cities voted for McKinley as he swept nearly all of the East and industrial Midwest, and did well along the border and the West Coast. Bryan swept the South and Mountain states and the wheat growing regions of the Midwest. Revivalistic Protestants cheered at Bryan's semi-religious rhetoric. Ethnic voters supported McKinley, who promised they would not be excluded from the new prosperity, as did more prosperous farmers and the fast-growing middle class.[43][44]

McKinley won the election by a fairly comfortable margin, taking 51 percent of the popular vote and 271 electoral votes.[45] Democrats remained loyal to their champion after his defeat; many letters urged him to run again in the 1900 presidential election. William's younger brother, Charles W. Bryan, created a card file of supporters to whom the Bryans would send regular mailings to for the next thirty years.[46] The Populist Party fractured after the election; many Populists, including James Weaver, followed Bryan into the Democratic Party, while others followed Eugene V. Debs into the Socialist Party.[47]

War and peace: 1898–1900

Spanish–American War

Due to better economic conditions for farmers and the effects of the Klondike Gold Rush, free silver lost its potency as an electoral issue in the years following 1896. In 1900, President McKinley signed the Gold Standard Act, which put the United States on the gold standard. Bryan remained popular in the Democratic Party, and his supporters took control of party organizations throughout the country, but he initially resisted shifting his political focus from free silver.[48] Foreign policy emerged as an important issue due to the ongoing Cuban War of Independence against Spain, as many Americans supported Cuban independence. After the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898, beginning the Spanish–American War. Though wary of militarism, Bryan had long favored Cuban independence, and he supported the war.[49] He argued that "universal peace cannot come until justice is enthroned throughout the world. Until the right has triumphed in every land and love reigns in every heart, government must, as a last resort, appeal to force".[50]

The United States and its colonial possessions after the Spanish–American War

At Governor Silas A. Holcomb's request, Bryan recruited a two thousand man regiment for the Nebraska National Guard, and the soldiers of the regiment elected Bryan as their leader. Under Colonel Bryan's command, the regiment was transported to Camp Cuba Libre in Florida, but the fighting between Spain and the United States ended before the regiment was deployed to Cuba. Bryan's regiment remained in Florida for months after the end of the war, thereby preventing Bryan from taking an active role in the 1898 mid-term elections. Bryan resigned his commission and left Florida in December 1898 after the United States and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris.[49]

Bryan had supported the war as a means to gain Cuba's independence, but he was outraged that the Treaty of Paris granted the United States control over the Philippines. While many Republicans believed that the United States had an obligation to "civilize" the Philippines, Bryan strongly opposed what he saw as American imperialism. Despite his opposition to the annexation of the Philippines, Bryan urged his supporters to ratify the Treaty of Paris; he wanted to quickly bring an official end the war and then grant independence to the Philippines as soon as possible. With Bryan's support, the treaty was ratified in a close vote, bringing an official end to the Spanish–American War. In early 1899, the Philippine–American War broke out as Filipinos under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo sought to end American rule over the archipelago.[51]

Presidential election of 1900

Conservatives in 1900 ridiculed Bryan's eclectic platform.

The 1900 Democratic National Convention met in Kansas City, Missouri, the westernmost location that either major party had ever held a national convention. Some Democratic leaders opposed to Bryan had hoped to nominate Admiral George Dewey for president, but Bryan faced no significant opposition by the time of the convention, and he won his party's nomination unanimously. Bryan did not attend the convention, but he exercised control of the convention's proceedings via telegraph.[52] Bryan faced a decision regarding what issue his campaign would focus on. Many of his most fervent supporters wanted Bryan to continue his crusade for free silver, while Democrats from the Northeast advised Bryan to center his campaign on the growing power of trusts. Bryan, however, decided that his campaign would focus on anti-imperialism, partly as a way to unite the factions of the party and win over some Republicans.[53] The party platform contained planks supporting free silver and opposing the power of trusts, but imperialism was labeled as the "paramount issue" of the campaign. The party nominated former Vice President Adlai Stevenson to serve as Bryan's running mate.[54]

In his speech accepting the Democratic nomination, Bryan argued that the election represented "a contest between democracy and plutocracy." He also strongly criticized the U.S. annexation of the Philippines, comparing it to the British rule of the Thirteen Colonies. Bryan argued that the United States should refrain from imperialism, and should seek to become the "supreme moral factor in the world's progress and the accepted arbiter of the world's disputes."[55] By 1900, the American Anti-Imperialist League, which included individuals like Benjamin Harrison, Andrew Carnegie, Carl Schurz, and Mark Twain, had emerged as the primary domestic organization opposed to the continued American control of the Philippines. Many of the leaders of the league had opposed Bryan in 1896 and continued to distrust Bryan and his followers.[56] Despite this distrust, Bryan's strong stance against imperialism convinced most of the league's leadership to throw their support behind the Democratic nominee.[55]

1900 electoral vote results

Once again, the McKinley campaign established a massive financial advantage, while the Democratic campaign relied largely on Bryan's oratory.[57] In a typical day Bryan gave four hour-long speeches and shorter talks that added up to six hours of speaking. At an average rate of 175 words a minute, he turned out 63,000 words a day, enough to fill 52 columns of a newspaper.[58] The Republican Party's superior organization and finances boosted McKinley's candidacy, and, as in the previous campaign, most major newspapers favored McKinley. Bryan also had to contend with the Republican vice presidential nominee, Theodore Roosevelt, who had emerged as national celebrity in the Spanish–American War and proved to be a strong public speaker. Bryan's anti-imperialism failed to register with many voters, and as the campaign neared its end, Bryan increasingly shifted to attacks on corporate power. He once again sought the voter of urban laborers, telling them to vote against the business interests that had "condemn[ed] the boys of this country to perpetual clerkship."[59]

By election day, few believed that Bryan would win, and McKinley ultimately prevailed once again over Bryan. Compared to the results of 1896, McKinley increased his popular vote margin and picked up several Western states, including Bryan's home state of Nebraska.[60] The Republican platform of a strong American industrial economy proved to be more important to voters than questions of the morality of annexing the Philippines.[61] The election also confirmed the continuing organizational advantage of the Republican Party outside of the South.[60]

Between presidential campaigns, 1901–1907

After the election, Bryan returned to journalism and oratory, frequently appearing on the Chautauqua circuits.[62] In January 1901, Bryan published the first issue of his weekly newspaper, The Commoner, which echoed Bryan's long-standing political and religious themes. Bryan served as the editor and publisher of the newspaper, but Charles Bryan, Mary Bryan, and Richard Metcalfe also performed editorial duties when Bryan was traveling. The Commoner became one of the most widely-read newspapers of its era, boasting 145,000 subscribers approximately five years after its founding. Though the paper's subscriber base heavily overlapped with Bryan's political base in the Midwest, content from the papers was frequently re-printed by major newspapers in the Northeast. In 1902, Bryan, his wife, and his three children moved into Fairview, a mansion located in Lincoln; Bryan referred to the house as the "Monticello of the West," and frequently invited politicians and diplomats to visit.[63]

Bryan's defeat in 1900 cost him his status as the clear leader of the Democratic Party, and conservatives like David B. Hill and Arthur Pue Gorman moved to re-establish their control over the party and return it to the policies of the Cleveland era. Meanwhile, Roosevelt succeeded McKinley as president after the latter was assassinated in September 1901. Roosevelt prosecuted anti-trust cases and implemented other progressive policies, but Bryan argued that Roosevelt did not fully embrace progressive causes. Bryan called for a package of reforms, including a federal income tax, pure food and drug laws, a ban on corporate financing of campaigns, a constitutional amendment providing for the direct election of senators, local ownership of utilities, and the state adoption of the initiative and the referendum. He also criticized Roosevelt's foreign policy and attacked Roosevelt's decision to invite Booker T. Washington to dine at the White House.[64]

Bryan in 1908

Prior to the 1904 Democratic National Convention, Alton Parker, a New York judge and conservative ally of David Hill, was seen as the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination. Conservatives feared that Bryan would join with publisher William Randolph Hearst to block Parker's nomination. Seeking to appease Bryan and other progressives, Hill agreed to a party platform that omitted mention of the gold standard and criticized trusts.[65] Parker won the Democratic nomination, but Roosevelt won re-election by the largest popular vote margin since the Civil War. Parker's crushing defeat vindicated Bryan, who published a post-election edition of The Commoner that advised its readers: "Do not Compromise with Plutocracy."[66]

Bryan traveled to Europe in 1903, meeting with figures such as Leo Tolstoy, who shared some of Bryan's religious and political views.[67] In 1905, Bryan and his family embarked on a trip around the globe, visiting eighteen countries in Asia and Europe. Bryan funded the trip with public speaking fees and a travelogue that was published on a weekly basis.[68] Bryan was greeted by a large crowd upon his return to the United States in 1906, and was widely seen as the likely 1908 Democratic presidential nominee. Partly due to the efforts of muckraking journalists, voters had become increasingly open to progressive ideas since 1904. President Roosevelt himself had moved to the left, favoring federal regulation of railroad rates and meatpacking plants.[69] Yet Bryan continued to favor more far-reaching reforms, including federal regulation of banks and securities, protections for union organizers, and federal spending on highway construction and education. Bryan also briefly expressed support for the state and federal ownership of railroads in a manner similar to Germany, but backed down from this policy in the face of an intra-party backlash.[70]

Presidential election of 1908

Bryan speaking at the 1908 Democratic National Convention

Presidential Campaign button for Bryan

Roosevelt, who enjoyed wide popularity among most voters even while he alienated some corporate leaders, anointed Secretary of War William Howard Taft as his successor.[71] Meanwhile, Bryan reestablished his control over the Democratic Party, winning the endorsement of numerous local Democratic organizations. Conservative Democrats again sought to prevent Bryan's nomination, but were unable to unite around an alternative candidate. Bryan was nominated for president on the first ballot of the 1908 Democratic National Convention. He was joined on the Democratic ticket by John W. Kern, a senator from the swing state of Indiana.[72]

Bryan campaigned on a party platform that reflected his long held beliefs, but the Republican platform also advocated for progressive policies, leaving relatively few major differences between the two major parties. One issue that the two parties differed on concerned deposit insurance, as Bryan favored requiring national banks to provide deposit insurance. Bryan was largely able to unify the leaders of his own party, and his pro-labor policies won him the first presidential endorsement ever issued by the American Federation of Labor.[73] As in previous campaigns, Bryan embarked on a public speaking tour to boost his candidacy; he was later joined on the trail by Taft.[74]

Defying Bryan's confidence in his own victory, Taft decisively won the 1908 presidential election. Bryan won just a handful of states outside of the Solid South, as he failed to galvanize the support of urban laborers.[75] Bryan remains the only individual since the Civil War to lose three separate U.S. presidential elections as a major party nominee.[76] Since the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, Bryan and Henry Clay are the lone individuals who received electoral votes in three separate presidential elections but lost all three elections.[77]

1908 electoral vote results

Bryan remained an influential figure in republican politics, and, after Democrats took control of the House of Representatives in the 1910 mid-term elections, he appeared in the House of Representatives to argue for tariff reduction.[78] In 1909, Bryan came out publicly for the first time in favor of Prohibition. A lifelong teetotaler, Bryan had refrained from embracing Prohibition earlier because of the issue's unpopularity among many Democrats.[79] According to biographer Paolo Colletta, Bryan "sincerely believed that prohibition would contribute to the physical health and moral improvement of the individual, stimulate civic progress, and end the notorious abuses connected with the liquor traffic."[80]

In 1910, he also came out in favor of women's suffrage.[81] Bryan crusaded as well for legislation to support introduction of the initiative and referendum as a means of giving voters a direct voice, making a whistle-stop campaign tour of Arkansas in 1910.[82] Although some observers, including President Taft, speculated that Bryan would make a fourth run for the presidency, Bryan repeatedly denied that he had any such intention.[83]

Wilson presidency

1912 election

Bryan attending the 1912 Democratic National Convention

A growing rift in the Republican Party gave Democrats their best chance in years to win the presidency. Though Bryan would not seek the Democratic presidential nomination, his continuing influence in the party gave him a role in choosing the party's nominee. Bryan was intent on preventing the conservatives in the party from nominating their candidate of choice, as they had done in 1904. For a mix of practical and ideological reasons, Bryan ruled out supporting the candidacies of Oscar Underwood, Judson Harmon, and Joseph W. Folk, leaving two major candidates competing for his backing: New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson and Speaker of the House Champ Clark. As Speaker, Clark could lay claim to progressive accomplishments, including the passage of constitutional amendments providing for the direct election of senators and the establishment of a federal income tax. But Clark had alienated Bryan for his failure to lower the tariff, and Bryan viewed the Speaker as overly friendly to conservative business interests. Wilson had criticized Bryan in the past, but he had compiled a strong progressive record as governor. As the 1912 Democratic National Convention approached, Bryan continued to deny that he would seek the presidency, but many journalists and politicians suspected that Bryan hoped a deadlocked convention would turn to him.[84]

After the start of the convention, Bryan engineered the passage of a resolution stating that the party was "opposed to the nomination of any candidate who is a representative of, or under any obligation to, J. Pierpont Morgan, Thomas F. Ryan, August Belmont, or any other member of the privilege-hunting and favor-seeking class." Clark and Wilson won the support of most delegates on the first several presidential ballots of the Democratic convention, but each fell short of the necessary two-thirds majority. After Tammany Hall came out in favor Clark and the New York delegation threw its support behind the Speaker, Bryan announced that he would support Wilson. In explaining his decision, Bryan stated that he could "not be a party to the nomination of any man ... who will not, when elected, be absolutely free to carry out the anti-Morgan-Ryan-Belmont resolution." Bryan's speech marked the start of a long shift away from Clark, and Wilson would finally clinch the presidential nomination after over 40 ballots. Journalists attributed much of the credit for Wilson's victory to Bryan.[85]

In the 1912 presidential election, Wilson faced off against President Taft and former President Roosevelt, the latter of whom ran on the Progressive Party ticket. Bryan campaigned throughout the West on behalf of Wilson, while also offering advice to the Democratic nominee on various issues. The split in the Republican ranks helped give Wilson the presidency, and Wilson won over 400 electoral votes despite taking just 41.8 percent of the popular vote. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats expanded their majority in the House and gained control of the Senate, giving the party unified control of Congress and the presidency for the first time since the early 1890s.[86]

Secretary of State

Bryan served as Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson

Cartoon of Secretary of State Bryan reading war news in 1914

Upon taking office, Wilson named Bryan as Secretary of State. Bryan's extensive travels, popularity in the party, and support for Wilson in the 1912 election made him the obvious choice for what was traditionally considered to be the highest-ranking position in the Cabinet. Bryan took charge of a State Department that employed 150 officials in Washington and an additional 400 employees in embassies abroad. Early in Wilson's tenure, the president and the secretary of state broadly agreed on foreign policy goals, including the rejection of Taft's Dollar diplomacy.[87] They also shared many priorities in domestic affairs, and, with Bryan's help, Wilson orchestrated passage of laws that reduced tariff rates, imposed a progressive income tax, introduced new anti-trust measures, and established the Federal Reserve System. Bryan proved particularly influential in ensuring that the president, rather than private bankers, was empowered to appoint the members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.[88]

Secretary of State Bryan pursued a series of bilateral treaties in which both signatories promised to submit all disputes to an investigative tribunal. He quickly won approval from the president and the Senate to proceed with his initiative, and in mid-1913 El Salvador became the first nation to sign one of Bryan's treaties. 29 other countries, including every great power in Europe other than Germany and Austria-Hungary, also agreed to sign the treaties.[89] Despite Bryan's aversion to conflict, he oversaw U.S. interventions in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico.[90]

After World War I broke out in Europe, Bryan consistently advocated for U.S. neutrality between the Entente and the Central Powers. With Bryan's support, Wilson initially sought to stay out of the conflict, urging Americans to be "impartial in thought as well as action."[91] For much of 1914, Bryan attempted to bring a negotiated end to the war, but the leaders of both the Entente and the Central Powers were ultimately uninterested in American mediation. While Bryan remained firmly committed to neutrality, Wilson and others within the administration became increasingly sympathetic to the Entente. The March 1915 Thrasher incident, in which a German U-boat sank a British passenger ship with an American citizen onboard, provided a major blow to the cause of American neutrality. The May 1915 sinking of RMS Lusitania by another German U-boat further galvanized anti-German sentiment, as 128 Americans died in the incident. Bryan argued that the British blockade of Germany was equally as offensive as the German U-boat Campaign.[92] He also maintained that by traveling on British vessels, "an American citizen can, by putting his own business above his regard for this country, assume for his own advantage unnecessary risks and thus involve his country in international complications."[93] After Wilson sent an official message of protest to Germany, and refused to publicly warn Americans not to travel on British ships, Bryan delivered his letter of resignation to Wilson on June 8, 1915.[94]

Later career

Political involvement

Despite their differences over foreign policy, Bryan supported Wilson's 1916 re-election campaign. Though he did not attend as an official delegate, the 1916 Democratic National Convention suspended its own rules to allow Bryan to address the convention; Bryan delivered a well-received speech in which he strongly defended Wilson's domestic record. Bryan served as a campaign surrogate for Wilson in the 1916 campaign, delivering dozens of speeches, primarily to audiences west of the Mississippi River. Ultimately, Wilson narrowly prevailed over the Republican candidate, Charles Evans Hughes.[95] When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Bryan wrote Wilson, "Believing it to be the duty of the citizen to bear his part of the burden of war and his share of the peril, I hereby tender my services to the Government. Please enroll me as a private whenever I am needed and assign me to any work that I can do."[96] Wilson declined to appoint Bryan to a federal position, but Bryan did agree to Wilson's request to provide public support for the war effort through his speeches and articles.[97] After the war, despite some reservations, Bryan supported Wilson's unsuccessful effort to bring the United States into the League of Nations.[98]

After leaving office, Bryan spent much of his time advocating for the eight-hour day, a minimum wage, the right of unions to strike and, increasingly, women's suffrage and Prohibition.[99] Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment, providing for nationwide Prohibition, in 1917. Two years later, Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote nationwide. Both amendments were ratified in 1920.[100] During the 1920s, Bryan called for further reforms, including agricultural subsidies, the guarantee of a living wage, full public financing of political campaigns, and an end to legal gender discrimination.[101]

Some Prohibitionists and other Bryan supporters tried to convince the three-time presidential candidate to enter the 1920 presidential election, and a Literary Digest poll taken in mid-1920 ranked Bryan as the fourth-most popular potential Democratic candidate. Bryan, however, declined to seek public office, writing "if I can help this world to banish alcohol, and after that to banish war ... no office, no Presidency, can offer the honors that will be mine." He attended the 1920 Democratic National Convention as a delegate from Nebraska, but was disappointed by the nomination of Governor James M. Cox, who had not supported ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment. Bryan declined the presidential nomination of the Prohibition Party and refused to campaign for Cox, making the 1920 campaign the first presidential contest in over thirty years in which he did not actively campaign.[102]

Though he became less involved in Democratic politics after 1920, Bryan attended the 1924 Democratic National Convention as a delegate from Florida.[103] He helped defeat a resolution condemning the Ku Klux Klan because he expected that the organization would soon fold; Bryan disliked the Klan but never publicly attacked it.[104] He also strongly opposed the candidacy of Al Smith due to Smith's hostility towards Prohibition. After over 100 ballots, the Democratic convention nominated John W. Davis, a conservative Wall Street lawyer. To balance the conservative Davis with a progressive, the convention nominated Bryan's brother, Charles Bryan, for vice president. Bryan was disappointed by the nomination of Davis, but strongly approved of the nomination of his brother, and he delivered numerous campaign speeches on behalf of the Democratic ticket. Davis suffered one of the worst losses in the Democratic Party's history, taking just 29 percent of the vote against Republican President Calvin Coolidge and third party candidate Robert M. La Follette.[105]

Florida real estate promoter

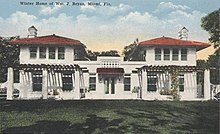

Villa Serena, Bryan's home built in 1913 at Miami, Florida

To help Mary cope with her worsening health during the harsh winters of Nebraska, the Bryans bought a farm in Mission, Texas in 1909.[106] Due to Mary's arthritis, in 1912 the Bryans began building a new home in Miami, Florida, known as Villa Serena. The Bryans made Villa Serena their permanent home, while Charles Bryan continued to oversee The Commoner from Lincoln. The Bryans were active citizens in Miami, leading a fundraising drive for the YMCA and frequently hosting the public at their home.[107] Bryan undertook lucrative speaking engagements, often serving as a spokesman for George E. Merrick's new planned community of Coral Gables.[108] His promotions probably contributed to the Florida real estate boom of the 1920s, which collapsed within months of Bryan's death in 1925.[citation needed]

Anti-evolution activism

In the 1920s, Bryan shifted his focus away from politics, becoming one of the most prominent religious figures in the country.[109] He held a weekly Bible class in Miami and published several religiously themed books.[110] He was one of the first individuals to preach religious faith on the radio, reaching audiences across the country.[111] Bryan welcomed the proliferation of faiths other than Protestant Christianity, but he was deeply concerned by the rejection of Biblical literalism by many Protestants.[112] According to historian Ronald L. Numbers, Bryan was not nearly as much a fundamentalist as many modern-day creationists of the 21st century. Instead he is more accurately described as a "day-age creationist".[113] Bradley J. Longfield posits Bryan was "theologically conservative social gospeler".[114]

In the final years of his life, Bryan became the unofficial leader of a movement that sought to prevent Charles Darwin's theory of evolution from being taught in public schools.[109] Bryan had long expressed skepticism and concern regarding Darwin's theory; in his famous 1909 Chautauqua lecture, "The Prince of Peace", Bryan had warned that the theory of evolution could undermine the foundations of morality.[115] Bryan opposed Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection for two reasons. First, he believed that what he considered a materialistic account of the descent of man (and all life) through evolution was directly contrary to the Biblical creation account. Second, he considered Darwinism as applied to society (social Darwinism) to be a great evil force in the world, promoting hatred and conflicts and inhibiting upward social and economic mobility of the poor and oppressed.[116]

Charles W. and William J. Bryan

As part of his crusade against Darwinism, Bryan called for state and local laws banning public schools from teaching evolution.[117] He requested that lawmakers refrain from attaching a criminal penalty to the anti-evolution laws, and also urged that educators be allowed to teach evolution as a "hypothesis" rather than as a fact. Only five states, all of them located in the South, responded to Bryan's call to bar the teaching of evolution in public schools.[118]

Bryan was worried that the theory of evolution was gaining ground not only in the universities, but also within the church. The developments of 19th century liberal theology, and higher criticism in particular, had allowed many clergymen to be willing to embrace the theory of evolution and claim that it was not contradictory with their being Christians. Determined to put an end to this, Bryan, who had long served as a Presbyterian elder, decided to run for the position of Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, which was at the time embroiled in the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy. Bryan's main competition in the race was the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the College of Wooster in Ohio, who had loudly endorsed the teaching of the theory of evolution in the college. Bryan lost to Wishart by a vote of 451–427. Bryan failed in gaining approval for a proposal to cut off funds to schools where the theory of evolution was taught. Instead, the General Assembly announced disapproval of materialistic (as opposed to theistic) evolution.[citation needed]

Scopes Trial

Congresswoman Ruth Bryan Owen, Bryan's daughter

In 1925, Bryan participated in the highly publicized Scopes Trial, which tested the Butler Act, a Tennessee law barring the teaching of evolution in public schools. The defendant, John T. Scopes, had violated the Butler Act while serving as a substitute biology teacher in Dayton, Tennessee. His defense was funded by the American Civil Liberties Union and led in court by famed lawyer Clarence Darrow. No one disputed that Scopes had violated the Butler Act, but Darrow argued that the statute violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. Bryan defended the right of parents to choose what schools teach, argued that Darwinism was merely a "hypothesis," and claimed that Darrow and other intellectuals were trying to invalidate "every moral standard that the Bible gives us."[119]

The defense called Bryan as a witness and asked him about his belief in the literal word of the Bible.[120] "Asked when the Flood occurred, Bryan consulted Ussher's Bible Concordance, and gave the date as 2348 BC, or 4,273 years ago. Did not Bryan know, asked Darrow, that Chinese civilization had been traced back at least 7,000 years? Bryan conceded that he did not. When he was asked if the records of any other religion made mention of a flood at the time he cited, Bryan replied: "The Christian religion has always been good enough for me—I never found it necessary to study any competing religion.' "[121] The judge expunged Bryan's testimony and instructed the jury to render a verdict of guilty; Scopes was fined $100 for violating the Butler Act.[122]

The national media reported the trial in great detail, with H. L. Mencken ridiculing Bryan as a symbol of Southern ignorance and anti-intellectualism.[citation needed] Even many Southern newspapers criticized Bryan's performance in the trial; the Memphis Commercial Appeal reported that "Darrow succeeded in showing that Bryan knows little about the science of the world." Bryan had not been allowed to deliver a final argument at trial, but he arranged for the publication of the speech he had intended to give. In that publication, Bryan wrote that "science is a magnificent material force, but it is not a teacher of morals."[123]

Death

In days following the Scopes Trial, Bryan delivered several speeches in Tennessee. On Sunday, July 26, 1925, Bryan died in his sleep after attending a church service in Dayton.[124] Bryan's body was transported by rail from Dayton to Washington, D.C. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, with an epitaph that read "Statesman. Yet Friend To Truth! Of Soul Sincere. In Action Faithful. And In Honor Clear"[125] and on the other side "He kept the faith"[126]

Family

William Jennings Bryan and wife Mary in New York City, June 19, 1915

Bryan remained married to his wife, Mary, until his death in 1925. Mary served as an important adviser to her husband; she passed the bar exam and learned German in order to help his career.[127] She was buried next to Bryan after her death in 1930.[128] William and Mary had three children: Ruth, William Jr., and Grace. Ruth won election to Congress in 1928, and later served as the ambassador to Denmark during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt.[129] William Jr. graduated from Georgetown Law and established a legal practice in Los Angeles. Grace also moved to Southern California and wrote a biography of her father. William Jr. held several federal positions and emerged as an important figure in the Los Angeles Democratic Party.[130] William Sr.'s brother, Charles, was an important supporter of his brother until William's death, as well as an influential politician in his own right. Charles served two terms as the mayor of Lincoln and three terms as the governor of Nebraska, and was the Democratic vice presidential nominee in the 1924 presidential election.[131]

Legacy

Historical reputation and political legacy

Statue of Bryan on the lawn of the Rhea County, Tennessee courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee

Bryan elicited mixed views during his lifetime, and his legacy remains complicated.[132] Author Scott Farris argues that "many fail to understand Bryan because he occupies a rare space in society ... too liberal for today's religious [and] too religious for today's liberals."[133] Jeff Taylor rejects the view that Bryan was a "pioneer of the welfare state" and a "forerunner of the New Deal," but argues that Bryan was more accepting of an interventionist federal government than his Democratic predecessors had been.[134] Biographer Michael Kazin, however, opines that

Bryan was the first leader of a major party to argue for permanently expanding the power of the federal government to serve the welfare of ordinary Americans from the working and middle classes ... he did more than any other man—between the fall of Grover Cleveland and the election of Woodrow Wilson—to transform his party from a bulwark of laissez-faire to the citadel of liberalism we identify with Franklin D. Roosevelt and his ideological descendants.[76]

Kazin argues that, compared to Bryan, "only Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had a greater impact on politics and political culture during the era of reform that began in the mid-1890s and lasted until the early 1920s."[135] Writing in 1931, former Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo stated that "with the exception of the men who have occupied the White House, Bryan ... had more to do with the shaping of the public policies of the last forty years than any other American citizen."[136] Historian Robert D. Johnston notes that Bryan was "arguably [the] most influential politician from the Great Plains."[137] In 2015, political scientist Michael G. Miller and historian Ken Owen ranked Bryan as one of the most four most influential American politicians who never served as president, alongside Alexander Hamilton, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun.[138]

Kazin also emphasizes the limits of Bryan's influence, noting that "for decades after [Bryan]'s death, influential scholars and journalists depicted him as a self-righteous simpleton who longed to preserve an age that had already passed."[76] Writing in 2006, editor Richard Lingeman noted that "William Jennings Bryan is mainly remembered as the fanatical old fool Fredric March played in Inherit the Wind."[139] Similarly, in 2011, John McDermott wrote that "Bryan is perhaps best known as the sweaty crank of a lawyer who represented Tennessee in the Scopes trial. After his defence of creationism, he became a mocked caricature, a sweaty possessor of avoirdupois, bereft of bombast."[33] Kazin writes that "scholars have increasingly warmed to Bryan's motives, if not his actions" in the Scopes Trial, due to Bryan's rejection of eugenics, a practice that many evolutionists of the 1920s favored.[140]

Kazin also notes the stain that Bryan's acceptance of the Jim Crow system places on his legacy, writing

His one great flaw was to support, with a studied lack of reflection, the abusive system of Jim Crow—a view that was shared, until the late 1930s, by nearly every white Democrat ... After Bryan's death in 1925, most intellectuals and activists on the broad left rejected the amalgam that had inspired him: a strict populist morality based on a close read reading of Scripture ... Liberals and radicals from the age of FDR to the present have tended to scorn that credo as naïve and bigoted, a remnant of an era of white Protestant supremacy that has, or should have, passed.[76]

Nonetheless, prominent individuals from both parties have praised Bryan and his legacy. In 1962, former President Harry Truman said Bryan "was a great one—one of the greatest." Truman also claimed: "If it wasn't for old Bill Bryan, there wouldn't be any liberalism at all in the country now. Bryan kept liberalism alive, he kept it going."[141][incomplete short citation]Tom L. Johnson, the progressive mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, referred to Bryan's campaign in 1896 as "the first great struggle of the masses in our country against the privileged classes."[citation needed] In a 1934 speech dedicating a memorial to Bryan, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said

I think that we would choose the word 'sincerity' as fitting him [Bryan] most of all ... it was that sincerity that served him so well in his life-long fight against sham and privilege and wrong. It was that sincerity which made him a force for good in his own generation and kept alive many of the ancient faiths on which we are building today. We ... can well agree that he fought the good fight; that he finished the course; and that he kept the faith.[142]

More recently, conservative Republicans such as Ralph Reed have hailed Bryan's legacy; Reed described Bryan as "the most consequential evangelical politician of the twentieth century."[143] Bryan's career has also frequently been compared to that of Donald Trump.[132]

In popular culture

Inherit the Wind, a 1955 play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, is a highly fictionalized account of the Scopes Trial written in response to McCarthyism. A populist thrice-defeated presidential candidate from Nebraska named Matthew Harrison Brady (based on Bryan) comes to a small town to help prosecute a young teacher for teaching evolution to his schoolchildren. He is opposed by a famous trial lawyer, Henry Drummond (based on Darrow), and mocked by a cynical newspaperman (based on H.L. Mencken) as the trial assumes a national profile. A 1960 Hollywood film adaptation, written by the playwrights, was directed by Stanley Kramer and stars Spencer Tracy as lawyer Henry Drummond and Fredric March as Matthew Harrison Brady.

L. Frank Baum satirized Bryan as the Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900. Baum had been a Republican activist in 1896 and wrote on McKinley's behalf.[144][145][146] Bryan appears as a character in Douglas Moore's 1956 opera The Ballad of Baby Doe. Bryan also has a biographical part in "The 42nd Parallel" in John Dos Passos' USA Trilogy.[147]Vachel Lindsay's "singing poem" "Bryan, Bryan, Bryan, Bryan" is a lengthy tribute to the idol of the poet's youth. The actor Ainslie Pryor played Bryan in a 1956 episode of the CBS anthology series You Are There. The short story "Plowshare" by Martha Soukup and part of the novel Job: A Comedy of Justice by Robert A. Heinlein are set in worlds where Bryan became president. Bryan also appears in And Having Writ by Donald R. Bensen.

Memorials

The William Jennings Bryan House in Nebraska was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1963. The Bryan Home Museum is a by-appointment only museum at his birthplace in Salem, Illinois. Salem is also home to Bryan Park and a large statue of Bryan. His home at Asheville, North Carolina, from 1917 to 1920, the William Jennings Bryan House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.[148]Villa Serena, Bryan's property in Miami, Florida, is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

A statue of Bryan represents the state of Nebraska at the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol, as part of the National Statuary Hall Collection. Bryan was named to the Nebraska Hall of Fame in 1971, and a bust of him resides in the Nebraska State Capitol.[149] Bryan was honored by the United States Postal Service with a $2 Great Americans series postage stamp.

Numerous objects, places, and people have been named after Bryan, including Bryan County, Oklahoma,[150]Bryan Medical Center in Lincoln, Nebraska, and Bryan College, located in Dayton, Tennessee. Omaha Bryan High School and Bryan Middle School in Bellevue, Nebraska are also named for Bryan. During World War II the Liberty ship SS William J. Bryan was built in Panama City, Florida, and named in his honor.[151]

See also

- Bryan Money (numismatics)

- Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy

- Progressive Era

Notes

^ Asked when his family "dropped the 'O'" from his O'Bryan surname, he replied there had never been one.[4]

^ The tax would be struck down by the Supreme Court in the 1895 case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co..[30]

^ U.S. senators were elected by the state legislature prior to the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913

References

^ Nimick, John (July 27, 1925). "Great Commoner Bryan dies in sleep, apoplexy given as cause of death". UPI Archives. Retrieved December 26, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ William Jennings Bryan Nebraska State Historical Society

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 4–5

^ Bryan Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan, pp. 22–26.

^ Colletta (1964), p. 3–5.

^ Kazin (2006), p. 5

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 4–5, 9

^ Kazin (2006), p. 8

^ "PCA History On This Day March 19: William Jennings Bryan". PCA History. March 19, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 10–11

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 8–9

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 9–10

^ Kazin (2006), p. 12

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 13–14

^ Colletta (1964), p. 30.

^ Colletta (1964), p. 21.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 15–17

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 17–18

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 17–19

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 22–24

^ Kazin (2006), p. 25

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 25–27

^ Colletta (1964), p. 48.

^ Kazin (2006), p. 27

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 31–34

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 20–22

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 33–36

^ Hibben (1929), p. 175.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 35–38

^ ab Kazin (2006), p. 51

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 40–43

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 46–48

^ ab McDermott, John (19 August 2011). "The life of Bryan, or what did monetary policy ever do for us?". Financial Times.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 53–55, 58

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 56–62

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 62–63

^ Glass, Andrew (19 March 2012). "William Jennings Bryan born, March 19, 1860". Politico. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

^ Kazin (2006), p. 63

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 63–65

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 65–67

^ William Safire (2004). Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History. W.W. Norton. p. 922.

^ Richard J. Ellis And Mark Dedrick, "The Presidential Candidate, Then and Now" Perspectives on Political Science (1997) 26#4 pp 208-216 online

^ Michael Nelson (2015). Guide to the Presidency. Routledge. p. 363.

^ Karl Rove (2016). The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters. pp. 367–69.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 76–79

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 80–82

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 202–203

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 83–86

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 86–89

^ Sicius (2015), p. 182

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 89–91

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 98–99

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 95–98

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 99–100

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 102–103

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 91–92

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 104–105

^ Coletta (1964), p. 272

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 105–107

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 107–108

^ Clements (1982), p. 38.

^ Kazin (2006), p. 122

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 111–113

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 113–114

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 114–116

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 119–120

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 126–128

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 121–122

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 142–143

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 145–149

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 151–152

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 152–154

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 154–157

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 159–160

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 163–164

^ abcd Kazin (2006), p. xix

^ Klotter, James C. (2018). Henry Clay: The Man Who Would Be President. Oxford University Press. p. xvii. ISBN 9780190498054.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 179–181

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 172–173

^ Coletta (1969, Vol. 2), p. 8

^ Kazin (2006), p. 177

^ Steven L. Piott, Giving Voters a Voice: The Origins of the Initiative and Referendum in America (2003) pp. 126–32

^ Kazin (2006), p. 173

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 181–184

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 187–191

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 191–192, 215

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 215–217, 222–223

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 223–227

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 217–218

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 229–231

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 232–233

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 234–236

^ Levine (1987), p. 8

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 237–238

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 248–252

^ Hibben (1929), p. 356

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 254–255

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 258–260

^ Kazin (2006), p. 245

^ Kazin (2006), p. 258

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 267–268

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 269–271

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 282–283

^ Coletta (1969, Vol. 3), pp. 162, 177, 184

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 283–285

^ Kazin (2006), p. 170

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 245–247

^ George, Paul S. "Brokers, Binders & Builders: Greater Miami's Boom of the Mid-1920s." Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 59, no. 4. 1981. pp. 440–63.

^ ab Kazin (2006), pp. 262–263

^ Florida Memory. "William Jennings Bryan Conducting a Bible Class in Royal Palm Park - Miami, Florida". Retrieved August 17, 2018.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 271–272

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 272–273

^ Ronald L. Numbers, The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design, (2006), p. 13

^ Longfield, Bradley J. "The Presbyterian Controversy". Retrieved August 17, 2018.

^ See The Prince of Peace

^ Coletta, (1969, Vol. 3), ch. 8

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 274–275

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 280–281

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 285–288

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 292–293

^ Paul Y. Anderson, "Sad Death of a Hero," American Mercury, v. 37, no. 147 (March 1936) 293–301.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 293–295

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 294–295

^ Kazin (2006), p. 294

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 296–297

^ Find a Grave. "William Jennings Bryan Find a Grave Memorial". Retrieved August 17, 2018.

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 14, 296

^ https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9058097/mary-elizabeth-bryan

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 300–301

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 266–267, 300–301

^ Kazin (2006), pp. 198–199

^ ab Rothman, Lily (24 February 2017). "The Man Steve Bannon Compared to President Trump, as Described in 1925". Time. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

^ Farris (2013), pp. 93–94

^ Taylor (2006), pp. 187–188

^ Kazin (2006), p. xiv

^ Kazin (2006), p. 304

^ Johnston, Robert D. (2011). ""There's No 'There' There": Reflections on Western Political Historiography". Western Historical Quarterly. 42 (3): 334.

^ Masket, Seth (19 November 2015). "A bracket to determine the most influential American who never became president". Vox. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

^ Lingeman, Richard (5 March 2006). "The Man With the Silver Tongue". New York Times.

^ Kazin (2006), p. 263

^ Merle Miller, pp. 118–19

^ "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Address at a Memorial to William Jennings Bryan". ucsb.edu.

^ Kazin (2006), p. 302

^ John G. Geer and Thomas R. Rochon, "William Jennings Bryan on the Yellow Brick Road," The Journal of American Culture Volume 16 Issue 4, (June 2004) pp. 59–63 doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1993.00059.x

^ Dighe, Ranjit S. (2002). The Historian's Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum's Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 31–32.

^ Rockoff, Hugh (1990). "The" Wizard of Oz" as a monetary allegory". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (4): 739–60. doi:10.1086/261704. JSTOR 2937766.

^ Dos Passos, John (1896–1970). U.S.A. Daniel Aaron & Townsend Ludington, eds. New York: Library of America, 1996.

^ National Park Service (July 9, 2010). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

^ "Nebraska Hall of Fame Members". nebraskahistory.org.

^ Oklahoma Historical Society. "Origin of County Names in Oklahoma", Chronicles of Oklahoma 2:1 (March 1924) 7582 (retrieved August 18, 2006).

^ Williams, Greg H. (July 25, 2014). The Liberty Ships of World War II: A Record of the 2,710 Vessels and Their Builders, Operators and Namesakes, with a History of the Jeremiah O'Brien. McFarland. ISBN 1476617546. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

Works cited

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Clements, Kendrick A. (1982). William Jennings Bryan, Missionary Isolationist. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9780870493645.- Coletta, Paolo E. William Jennings Bryan 3 vols. online vol 1; online vol 2; online vol 3

Coletta, Paolo E. (1964). William Jennings Bryan, Vol. 1: Political Evangelist, 1860-1908. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803200227.

Coletta, Paolo E. (1969). William Jennings Bryan, Vol. 2: Progressive Politician and Moral Statesman. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803200234.

Coletta, Paolo E. (1969). William Jennings Bryan, Vol. 3: Political Puritan, 1915-1925. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803200241.

Coletta, Paolo E. (1984). "Will the Real Progressive Stand Up? William Jennings Bryan and Theodore Roosevelt to 1909". Nebraska History. 65: 15–57.

Farris, Scott (2013). Almost President: The Men Who Lost the Race but Changed the Nation. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780762784219.

Hibben, Paxton (1929). The Peerless leader, William Jennings Bryan. Farrar and Rinehart, Incorporated.

Kazin, Michael (2006). A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Knopf. ISBN 978-0375411359.

Levine, Lawrence W. (1965). Defender of The Faith: William Jennings Bryan: The Last Decade 1915-1925. Oxford University Press.

Rove, Karl (2016). The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters. Simon and Schuster.

Thompson, Charles Willis (June 13, 1925). "Silver-Tongue". Profiles. The New Yorker. 1 (17): 9–10.

Sicius, Francis J. (2015). The Progressive Era: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610694476.

Taylor, Jeff (2006). Where Did the Party Go?: William Jennings Bryan, Hubert Humphrey, and the Jeffersonian Legacy. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1659-5.

Further reading

Biographies

Cherny, Robert W. (1985). A Righteous Cause: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0316138543.

Glad, Paul W. (1960). The trumpet soundeth; William Jennings Bryan and his democracy, 1896-1912. University of Nebraska Press. OCLC 964829.

Koenig, Louis William (1971). Bryan: A Political Biography of William Jennings Bryan. Putnam Pub Group. ISBN 978-0399101045.

Leinwand, Gerald (2006). William Jennings Bryan: An Uncertain Trumpet. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742551589.

Werner, M. R. (1929). William Jennings Bryan. Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 1517464.

Specialized studies

Barnes, James A. (1947). "Myths of the Bryan Campaign". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 34 (3): 367–404. doi:10.2307/1898096. JSTOR 1898096. on 1896

Bensel, Richard Franklin (2008). Passion and Preferences: William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Democratic National Convention. Cambridge U.P. ISBN 9780521717625.

Cherny, Robert W. (1996). "William Jennings Bryan and the Historians" (PDF). Nebraska History. 77 (3–4): 184–93. ISSN 0028-1859. Analysis of the historiography.

Clements, Kendrick A. (1992). The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0523-1.

Edwards, Mark (2000). "Rethinking the Failure of Fundamentalist Political Antievolutionism after 1925". Fides et Historia. 32 (2): 89–106. ISSN 0884-5379. PMID 17120377. Argues that fundamentalists thought they had won Scopes trial but death of Bryan shook their confidence.

Folsom, Burton W. (1999). No More Free Markets Or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900–1924. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739100141.

Glad, Paul W. (1964). McKinley, Bryan and the People. Lippincott. OCLC 559539520.

Hohenstein, Kurt (2000). "William Jennings Bryan and the Income Tax: Economic Statism and Judicial Usurpation in the Election of 1896". Journal of Law & Politics. 16 (1): 163–92. ISSN 0749-2227.

Jeansonne, Glen (1988). "Goldbugs, Silverites, and Satirists: Caricature and Humor in the Presidential Election of 1896". Journal of American Culture. 11 (2): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1988.1102_1.x. ISSN 0191-1813.

Larson, Edward (1997). Summer for the Gods: The Scopes trial and America's continuing debate over science and religion. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07509-6.

Longfield, Bradley J. (2000). "For Church and Country: the Fundamentalist-modernist Conflict in the Presbyterian Church". Journal of Presbyterian History. 78 (1): 34–50. ISSN 0022-3883. Puts Scopes in larger religious context.

Magliocca, Gerard N. (2014). The Tragedy of William Jennings Bryan: Constitutional Law and the Politics of Backlash. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300205824.

Mahan, Russell L. (2003). "William Jennings Bryan and the Presidential Campaign of 1896". White House Studies. 3 (2): 215–27. ISSN 1535-4768.

Murphy, Troy A. (2002). "William Jennings Bryan: Boy Orator, Broken Man, and the 'Evolution' of America's Public Philosophy". Great Plains Quarterly. 22 (2): 83–98. ISSN 0275-7664.- Rove, Karl. (2015) The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters, Simon & Schuster,

ISBN 978-1476752952. Detailed narrative of the entire campaign by Karl Rove, a prominent 21st-century Republican campaign advisor.

Scroop, Daniel (2013). "William Jennings Bryan's 1905–1906 World Tour" (PDF). Historical Journal. 56 (2): 459–86. doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000520.

Smith, Willard H. (1966). "William Jennings Bryan and the Social Gospel". Journal of American History. 53 (1): 41–60. doi:10.2307/1893929. JSTOR 1893929.

Williams, R. Hal (2010). Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1721-0.

Wood, L. Maren (2002). "The Monkey Trial Myth: Popular Culture Representations of the Scopes Trial". Canadian Review of American Studies. 32 (2): 147–64. doi:10.3138/CRAS-s032-02-01. ISSN 0007-7720.

Writings by Bryan

- Bryan, William Jennings. William Jennings Bryan: selections ed. by Ray Ginger (1967) 259 pp

- Bryan, William Jennings. The first battle: a story of the campaign of 1896 (1897), 693 pp; campaign speeches online edition

The Commoner Condensed, annual compilation of The Commoner magazine; full text online for 1901, 1902, 1903, 1907, 1907, 1908- Bryan, William Jennings. The old world and its ways (1907) 560 pages full text online

- Bryan, William Jennings. Speeches of William Jennings Bryan edited by Mary Baird Bryan (1909) full text online

- Bryan, William Jennings. In His image (1922) 226 pp full text online

- Bryan, William Jennings. The Memoirs: of William Jennings Bryan, by himself and his wife (1925) 560 pp; online edition

- Bryan, William Jennings. British Rule in India (1906) Online Edition

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Jennings Bryan. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Jennings Bryan |

Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Jennings Bryan |

United States Congress. "William Jennings Bryan (id: B000995)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Works by William Jennings Bryan at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about William Jennings Bryan at Internet Archive

Works by William Jennings Bryan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

William Jennings Bryan, Jr at Find a Grave

William Jennings Bryan cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.- "The Deity of Christ" – paper by Bryan on the subject

William Jennings Bryan papers at Nebraska State Historical Society- William Jennings Bryan Recognition Project (WJBP)

"William Jennings Bryan, Presidential Contender" from C-SPAN's The Contenders