Burning of Cork

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Workers clearing rubble on St Patrick's Street in Cork following the fires

The Burning of Cork by British forces took place on the night of 11–12 December 1920, during the Irish War of Independence. It followed an Irish Republican Army (IRA) ambush of a British Auxiliary patrol in the city, which wounded twelve Auxiliaries, one fatally. In retaliation, the Auxiliaries, Black and Tans and British soldiers looted and burnt numerous buildings in the city centre. Many civilians reported being beaten, shot at, and robbed by British forces. Firefighters testified that British forces hindered their attempts to tackle the blazes through intimidation, cutting their hoses and shooting at them.

More than 40 business premises, 300 residential properties, the City Hall and Carnegie Library were destroyed by the fire. Over £3 million worth of damage (equivalent to €172 million today) was wrought, 2,000 were left jobless and many more became homeless. Two unarmed IRA volunteers were shot dead in the north of the city.

British forces carried out other reprisals on Irish civilians during the war, but the burning of Cork was one of the most significant. The British government at first denied that its forces had started the fires, and blamed the IRA. Later, a British Army inquiry concluded that a company of Auxiliaries were responsible.

Contents

1 Background

2 Ambush at Dillon's Cross

3 Burning and looting

4 Shooting of the Delaney brothers

5 Aftermath

5.1 Investigation

6 See also

7 References

7.1 Notes

7.2 Sources

Background

The Irish War of Independence began in 1919, following the declaration of an Irish Republic and its parliament, Dáil Éireann. The army of the new republic, the Irish Republican Army (IRA), waged guerrilla warfare against British forces: the British Army and the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). To help fight the IRA, the British Government formed the Auxiliary Division; a paramilitary unit composed of ex-soldiers from Britain which specialized in counter-insurgency. It also recruited thousands of British ex-soldiers into the RIC, who became known as "Black and Tans". IRA intelligence officer Florence O'Donoghue claimed the subsequent burning and looting of Cork was "not an isolated incident, but rather the large-scale application of a policy initiated and approved, implicitly or explicitly, by the British government".[1]

A group of "Black and Tans" and Auxiliaries in Dublin, April 1921

County Cork was an epicenter of the war. On 23 November 1920, a "Black and Tan" in civilian dress threw a grenade into a group of IRA volunteers who had just left a brigade meeting on St Patrick Street in Cork. Three IRA volunteers of the 1st Cork Brigade were killed: Paddy Trahey, Patrick Donohue and Seamus Mehigan.[2]The New York Times reported that sixteen people were injured.[3]

On 28 November 1920, the IRA's 3rd Cork Brigade ambushed an Auxiliary patrol at Kilmichael, killing 17 Auxiliaries. This was the biggest loss of life for the British in County Cork. On 10 December, British forces declared martial law in counties Cork (including the city), Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary. It also imposed a military curfew on Cork city, which began at 10PM each night. IRA volunteer Seán Healy later recalled that "at least 1,000 troops would pour out of Victoria Barracks at this hour and take over complete control of the city".[4]

Ambush at Dillon's Cross

IRA intelligence established that an Auxiliary patrol usually left Victoria Barracks (in the north of the city) each night at 8PM and made its way to the city centre via Dillon's Cross. On 11 December, IRA commander Seán O'Donoghue received intelligence that two lorries of Auxiliaries would be leaving the barracks that night and travelling with them would be British Army Intelligence Corps Captain James Kelly.[4]

That evening, a unit of six IRA volunteers commanded by O'Donoghue took up position between the barracks and Dillon's Cross.[5] Their goal was to destroy the patrol and capture or kill Captain Kelly. Five of the volunteers hid behind a stone wall while one, Michael Kenny, stood across the road dressed as an off-duty British officer. When the lorries neared he was to beckon the driver of the first lorry to slow down or stop.[5] The neighbourhood was close (within a "couple of hundred yards") of a military barracks.[6][7]

At 8PM, two lorries each carrying 13 Auxiliaries emerged from the barracks. The first lorry slowed when the driver spotted Kenny and, as it did so, the IRA unit attacked with grenades and revolvers.[5] The official British report said that 12 members of the Auxiliary Division were wounded and that one, Temporary Cadet Spencer Chapman, a former Officer in the 4th Battalion London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), died from his wounds shortly after.[4][8] As the IRA unit made its escape, some of the Auxiliaries managed to fire their rifles in the direction of the volunteers while others dragged the wounded to the nearest cover: O'Sullivan's pub.[4]

The Auxiliaries broke into the pub with weapons drawn.[5] They ordered everyone to put their hands over their heads to be searched. Backup and an ambulance were sent from the nearby barracks. One witness described a number of young men being rounded-up and forced to lie on the ground. The Auxiliaries dragged one of them to the middle of the crossroads, stripped him naked and forced him to sing "God Save the King" until he collapsed on the road.[4]

Burning and looting

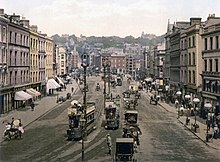

St Patrick's Street, Cork, c. 1900

Angered by an attack so near their headquarters and seeking retribution for the deaths of their colleagues at Kilmichael, the Auxiliaries gathered to wreak their revenge.[9] Charles Schulze, a member of the Auxiliaries and a former British Army Captain in the Dorsetshire Regiment during World War I, organized a group of Auxiliaries to burn the centre of Cork.[10]

At 9:30PM, lorries of Auxiliaries and British soldiers left the barracks and alighted at Dillon's Cross, where they broke into a number of houses and herded the occupants on to the street. They then set the houses on fire and stood guard as they were razed to the ground.[11] Those who tried to intervene were fired upon and some were badly beaten.[9] Seven buildings were set alight at the crossroads. When one was found to be owned by Protestants, the Auxiliaries quickly doused the fire.[12]

At about the same time, a group of armed and uniformed Auxiliaries surrounded a tram at Summerhill, smashed its windows, and forced all the passengers out.[13] A number of the passengers (including at least three women) were repeatedly kicked, hit with rifle butts, threatened, and verbally abused. The Auxiliaries then forced the passengers to line-up against a wall and searched them, while continuing the physical and verbal abuse. Some had their money and belongings stolen.[14] Another tram was set alight near Father Mathew's statue. Meanwhile, witnesses reported seeing a group of 14–18 Black and Tans firing wildly for upwards of 20 minutes on nearby MacCurtain Street.[15]

Soon after, witnesses reported groups of armed men on St Patrick's Street, the city's main shopping area. Some were uniformed or partially uniformed members of the Auxiliaries and British Army while others wore no uniforms.[16] They were seen firing into the air, smashing shop windows and setting buildings alight. Many reported hearing bombs exploding. A group of Auxiliaries were seen throwing a bomb into the ground floor of the Munster Arcade, which housed both shops and flats. It exploded under the residential quarters while people were inside the building. They managed to escape unharmed but were detained by the Auxiliaries.[16]

Cork City Hall in the 1870s. The building was destroyed during the Burning of Cork

The fire brigade was informed of the fire at Dillon's Cross shortly before 10 pm and were sent to deal with it at once. However, on finding that Grant's department store on St Patrick's Street was ablaze, they decided to tackle it first.[17] The fire brigade's Superintendent, Alfred Hutson, called Victoria Barracks and asked them to tackle the fire at Dillon's Cross so that he could focus on the city centre. However, the barracks took no heed of his request. As he did not have enough resources to deal with all the fires at once, "he would have to make choices – some fires he would fight, others he could not".[18]

Hutson oversaw the operation on St Patrick's Street, and met Cork Examiner reporter Alan Ellis. He told Ellis "that all the fires were being deliberately started by incendiary bombs, and in several cases he had seen soldiers pouring cans of petrol into buildings and setting them alight".[19]

A number of firemen later testified that British forces hindered their attempts to tackle the blazes by intimidating them, cutting their hoses and/or driving lorries over the hoses. They also said that firemen were shot at and that at least two were wounded by gunfire.[20] Shortly after 3AM, Cork Examiner reporter Alan Ellis came upon a unit of the fire brigade pinned down by gunfire near City Hall. The firemen said that they were being shot at by Black and Tans who had broken into the building. They also claimed to have seen uniformed men carrying cans of petrol into the building from nearby Union Quay barracks.[21]

At about 4AM a large explosion was heard and City Hall and the neighbouring Carnegie Library went up in flames, resulting in the loss of many of the city's public records.[21][22] When more firefighters arrived, British forces fired at them and refused them access to water. The last act of arson took place at about 6AM when a group of policemen looted and burnt the Murphy Brothers' clothes shop on Washington Street.[21]

Shooting of the Delaney brothers

After the ambush at Dillon's Cross, IRA commander Seán O'Donoghue and volunteer James O'Mahony made their way to the Delaney farmhouse at Dublin Hill in the north of the city. Brothers Cornelius and Jeremiah Delaney were members of F Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Cork Brigade IRA.[23]

O'Donoghue hid a number of unused grenades on the farm and the two men went their separate ways.[24] At about 2AM at least eight armed men entered the house and went upstairs into the brothers' bedroom. The brothers got up and stood at the bedside and were asked their names. When they answered, the gunmen opened fire.[23][25] Both brothers were shot dead and their elderly relative, William Dunlea, was wounded by gunfire.[26] According to Daniel Delaney, the father of the brothers, the gunmen wore long overcoats and spoke with English accents.[23] It is thought that, while searching the site of the ambush, the Auxiliaries had found a cap belonging to one of the volunteers and had used bloodhounds to follow the scent to the Delaney home.[27]

Aftermath

Fire engines sent from Dublin to help deal with the aftermath of the fires

Over 40 business premises and 300 residential properties had been destroyed.[28] This amounted to over five acres of the city.[29] Over £3 million worth of damage (1920 value) was suffered, although the value of property looted by British forces was not clear. Many people became homeless and 2,000 were left jobless.[10] Fatalities included an Auxiliary killed by the IRA, two IRA volunteers killed by Auxiliaries, and a woman who died from a heart-attack when Auxiliaries burst into her house. A number of people, including firefighters, had reportedly been assaulted or otherwise wounded.[28]

Florence O'Donoghue, intelligence officer of the 1st Cork Brigade IRA at the time, described the scene in Cork on the morning of the 12th:

"Many familiar landmarks were gone forever – where whole buildings had collapsed here and there a solitary wall leaned at some crazy angle from its foundation. The streets ran with sooty water, the footpaths were strewn with broken glass and debris, ruins smoked and smoldered and over everything was the all-pervasive smell of burning."[30]

At midday mass in the North Cathedral the Bishop of Cork, Daniel Cohalan, condemned the arson but said the burning of the city was a result of the "murderous ambush at Dillon's Cross" and vowed, "I will certainly issue a decree of excommunication against anyone who, after this notice, shall take part in an ambush or a kidnapping or attempted murder or arson".[31] No excommunications, however, were issued, and the bishop's edict was largely ignored by pro-IRA priests and chaplains.[32]

A meeting of Cork Corporation was held that afternoon at the Corn Exchange. Councillor J.J. Walsh condemned the bishop for his comments, which he claimed held the Irish people up as the "evil-doers". Walsh said that while the people of Cork had been suffering, "not a single word of protest was uttered [by the bishop], and today, after the city has been decimated, he saw no better course than to add insult to injury". Councillor Michael Ó Cuill, alderman Tadhg Barry and the Lord Mayor, Daniel O'Callaghan, agreed with Walsh's sentiments. The members resolved that the Lord Mayor should send a telegram asking for the intervention of the European governments and the USA.[33]

Three days after the fire, on 15 December, two lorry-loads of Auxiliaries were travelling from Dunmanway to Cork for the funeral of Spencer Chapman, a comrade killed at Dillon's Cross. When they met two men (an elderly priest, Canon Magner, walking with a parishioner, a farmer's son) helping a resident magistrate fix his car, an Auxiliary, Vernon Anwyl Hart, got out and began questioning them, then shot Magner and his companion, Timothy (or Tadhg) Crowley. Both died of their injuries. A military court of inquiry heard that he had been a friend of Chapman and had been "drinking steadily" since his death. Hart was found guilty of murder, but insane.[34] At a subsequent investigation, one of the reasons given for his murder was that he refused to have the parish church bells tolled after the Kilmichael ambush, in which 17 Auxiliaries were killed.[35]

Investigation

The re-built Cork City Hall, completed in the 1930s

Irish nationalists called for an open and impartial inquiry.[36] In the British House of Commons, Sir Hamar Greenwood, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, refused demands for such an inquiry. He denied that British forces had any involvement and accused the IRA of starting the fires.[22][37] When asked about reports of firefighters being hampered by British forces he said "Every available policeman and soldier in Cork was turned out at once and without their assistance the fire brigade could not have gone through the crowds and did the work that they tried to do".[37]

Bonar Law said "in the present condition of Ireland, we are much more likely to get an impartial inquiry in a military court than in any other".[36] The British military launched its own inquiry, the "Strickland Report",[38] but Cork Corporation instructed its employees and other corporate officials to take no part.[39] The report pointed the finger of blame at members of the Auxiliaries' K Company, based at Victoria Barracks. The Auxiliaries, it was claimed, set the fires in reprisal for the IRA attack at Dillon's Cross.[22] However, the British Government refused to publish the report.[38]

The Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress published a pamphlet in January 1921 entitled Who burned Cork City? The work drew on evidence from hundreds of eyewitness which suggested that the fires had been set by British forces and that British forces had prevented firefighters from tackling the blaze.[29] The material was compiled by the President of University College Cork, Alfred O'Rahilly.[22]

K Company Auxiliary Charles Schulze, a former British Army Captain,[40] wrote in a letter to his girlfriend in England that it was "sweet revenge", while in a letter to his mother he wrote: "Many who had witnessed scenes in France and Flanders say that nothing they had experienced was comparable with the punishment meted out in Cork".[10] After the fire, K Company was moved to Dunmanway and began wearing burnt corks in their caps in reference to the burning of the city.[29] For their part in the arson and looting, K Company was disbanded on 31 March 1921.[41]

There has been debate over whether British forces at Victoria Barracks had planned to burn the city before the ambush at Dillon's Cross, whether the British Army itself was involved, and whether those who set the fires were being commanded by superior officers. Florence O'Donoghue, who was intelligence officer of the 1st Cork Brigade IRA at the time, wrote:

"What appears more probable is that the ambush provided the excuse for an act which was long premeditated and for which all arrangements had been made. The rapidity with which supplies of petrol and Verey lights were brought from Cork barracks to the centre of the city, and the deliberate manner in which the work of firing the various premises was divided amongst groups under the control of officers, gives evidence of organisation and pre-arrangement. Moreover, the selection of certain premises for destruction and the attempt made by an Auxiliary officer to prevent the looting of one shop by Black and Tans: 'You are in the wrong shop; that man is a Loyalist' and the reply, 'We don't give a damn; this is the shop that was pointed out to us', is additional proof that the matter had been carefully planned beforehand."[42]

See also

- Sack of Balbriggan

References

Notes

^ O'Donoghue 2009, pp. 88–89.

^ Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History 1956, pp. 29–30.

^ New York Times 1920.

^ abcde White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 104–10.

^ abcd O'Brien 2017, chpt. 10.

^ O'Donoghue 2009, p. 93.

^ Bennett 2010.

^ "The Auxiliaries – Spencer R Chapman". Retrieved 14 August 2012

^ ab White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 111–12.

^ abc O'Riordan 2010.

^ O'Donoghue 2009, p. 94.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 114.

^ O'Donoghue 2009, p. 95.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 115–17.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 118-20.

^ ab White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 121–25.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 125.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 126.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 128.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 126-27.

^ abc White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 135–36.

^ abcd Cork History.

^ abc Delaney Brothers.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 109.

^ O'Donoghue 2009, p. 101.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 9.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 134.

^ ab Ellis 2004, p. 244.

^ abc Hidden History.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 139.

^ White & O'Shea 2006, pp. 140–42.

^ Coogan, Tim Pat."Clune arrived in Rome in the wake of the publicity over this decree and a growing belief, fostered by the British, that some priests were preaching that it was not a sin to shoot policemen. In fact the British were not entirely wide of the mark as the following letter to Florrie O'Donoghue, on Cohalan's edict, from the Chaplain to the Brigade shows", Michael Collins: A Biography, Head of Zeus Ltd, December 16, 2015 (524 pages); .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 1784975362/

ISBN 9781784975364

^ White & O'Shea 2006, p. 143.

^ Leeson 2011, p. 204.

^ Canon Magner murder, theauxiliaries.com; accessed 17 February 2018.

^ ab O'Donoghue 2009, p. 102.

^ ab White & O'Shea 2006, p. 148.

^ ab "Greenwood heckled on Strickland Report", The New York Times, 17 February 1921.

^ O'Donoghue 2009, p. 103.

^ Charles Schulze profile, theauxiliaries.com; accessed 17 February 2018.

^ Leeson 2011, p. 101.

^ O'Donoghue 2009, pp. 93–94.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Cork City Council. "History of Cork – Burning of Cork". Retrieved 28 May 2017.

Ellis, Peter (2004). Eyewitness to Irish History. John Wiley & Sons.

"Hidden History – The Burning of Cork". RTÉ News. Archived from the original on March 2008.

Bennett, Richard (2010). The Black and Tans. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473812420.

O'Brien, Paul (2017). Havoc: The Auxiliaries in Ireland’s War of Independence. Collins Press. ISBN 9781788410106.

Leeson, D. M. (2011). The Black and Tans: British Police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence. Oxford University Press.

"Murder of Delaney Brothers at Dublin Hill". Retrieved 28 May 2017.

New York Times (1920). "Two die from Cork explosion - 25 November 1920".

O'Donoghue, F. (2009). "The Sacking of Cork". In Ó Conchubhair, Brian. Rebel Cork's Fighting Story, 1916–21: Told by the Men who Made it: with a Unique Pictorial Record of the Period. Mercier Press Ltd. pp. 88–105. ISBN 978-1-85635-644-2.

O'Riordan, Sean (11 December 2010). "Culprit who led burning of Cork finally identified". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History (1956). "1913–21 Statement by Witness. Document No. W.S. 1547. Witness Michael Murphy" (PDF). Retrieved 28 May 2017.

White, Gerry; O'Shea, Brendan (2006). The Burning of Cork. Mercier Press. ISBN 1-85635-522-5.