Tarnów

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP Tarnów | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

Tarnów Show map of Lesser Poland Voivodeship  Tarnów Show map of Poland | |||

| Coordinates: 50°00′45″N 20°59′19″E / 50.01250°N 20.98861°E / 50.01250; 20.98861 | |||

| Country | Poland | ||

| Voivodeship | Lesser Poland | ||

| County | city county | ||

| Town rights | 7 March 1330 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Roman Ciepiela | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 72.4 km2 (28.0 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2013) | |||

| • City | 112,478 | ||

| • Density | 1,600/km2 (4,000/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 269,000 | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code | 33-100 to 33-110 | ||

| Area code(s) | +48 14 | ||

| Car plates | KT | ||

| Website | http://www.tarnow.pl | ||

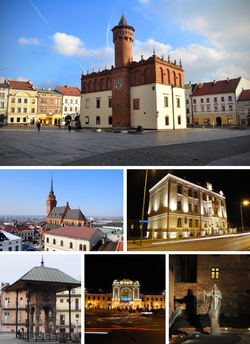

Tarnów (Polish pronunciation: [ˈtarnuf] (![]() listen); is a city in southeastern Poland with 115,341 inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of 269,000 inhabitants. The city is situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship since 1999. From 1975 to 1998, it was the capital of the Tarnów Voivodeship. It is a major rail junction, located on the strategic east–west connection from Lviv to Kraków, and two additional lines, one of which links the city with the Slovak border. Tarnów is known for its traditional Polish architecture, which was strongly influenced by foreign cultures and foreigners that once lived in the area, most notably Jews, Germans and Austrians.[1] The entire Old Town, featuring 16th century tenements, houses and defensive walls, has been fully preserved. Tarnów is also the warmest city of Poland, with the highest long-term mean annual temperature in the whole country.[2]

listen); is a city in southeastern Poland with 115,341 inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of 269,000 inhabitants. The city is situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship since 1999. From 1975 to 1998, it was the capital of the Tarnów Voivodeship. It is a major rail junction, located on the strategic east–west connection from Lviv to Kraków, and two additional lines, one of which links the city with the Slovak border. Tarnów is known for its traditional Polish architecture, which was strongly influenced by foreign cultures and foreigners that once lived in the area, most notably Jews, Germans and Austrians.[1] The entire Old Town, featuring 16th century tenements, houses and defensive walls, has been fully preserved. Tarnów is also the warmest city of Poland, with the highest long-term mean annual temperature in the whole country.[2]

Contents

1 Names and etymology

2 History

2.1 Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

2.2 Habsburg Empire

2.3 Second Polish Republic

2.4 1939 invasion of Poland

2.5 The Jews of Tarnów

2.6 Holocaust resistance

3 Geography

3.1 Climate

4 Economy

5 Transport

6 Politics

7 Attractions

8 Education

9 Sports

10 Religion

11 International relations

11.1 Twin towns — Sister cities

12 Notable residents

13 Notes

14 References

Names and etymology

The first documented mention of the settlement dates back to 1105, spelled as Tharnow. The name later evolved to Tarnowo (1229), Tarnów (1327), and Tharnow (1473).[3] The place name Tarnów is widely used in different forms across Slavic Europe, and lands which used to be inhabited by Slavs, such as eastern Germany, Hungary, and northern Greece. There is a German town, Tarnow, Greek Tyrnavos (also spelled as Tirnovo), Czech Trnov, Bulgarian Veliko Tarnovo and Malko Tarnovo, as well as different Trnovos/Trnowos in Slovenia, Slovakia, Serbia, Bosnia, and Macedonia. The name Tarnów comes from an early Slavic word trn/tarn, which means "thorn", or an area covered by thorny plants.

History

Polish Gothic-styled Cathedral located in the Old Town district

Casimir the Great Square

Already in the mid-9th century, on the Tarnów’s St. Martin Mount (Góra sw. Marcina, 2.5 kilometes from the centre of today’s city), a Slavic gord was established, probably by the Vistulans. Due to efforts of local archaeologists, we know that the size of the gord was almost 16 hectares, and it was surrounded by a rampart. The settlement was probably destroyed in the 1030s or the 1050s, during either a popular rebellion against Christianity (see Baptism of Poland), or Czech invasion of Lesser Poland. In the mid-11th century, a new gord was established on the Biała river. It was a royal property, which in the late 11th or early 12th century was handed over to the Tyniec Benedictine Abbey. The name Tarnów, with a different spelling, was for the first time mentioned in a document of Papal legate, Cardinal Gilles de Paris (1124).[3]

The first documented mention of Tarnów occurs in the year 1309, when a list of miracles of Kinga of Poland specifies a woman named Marta, who was resident of the settlement. In 1327, a knight named Spicymir (Leliwa coat of arms) purchased a village of Tarnów Wielki, and three years later, founded his own private town. On March 7, 1330, King Władysław I the Elbow-high granted Magdeburg rights to Tarnów. In the same year, construction of a castle on the St. Martin Hill was completed by Castellan of Kraków, Spycimir Leliwita of Leliwa coat of arms (its ruins can still be seen).

Tarnów remained in the hands of the Leliwa family, out of which in the 15th century the Tarnowski family emerged. In the 14th century, numerous German settlers immigrated from Kraków and Nowy Sącz (see Walddeutsche, Ostsiedlung). During the 17th century Scottish immigrants began to come in large numbers. In 1528 the exiled King of Hungary János Szapolyai lived in the town.[4] The town prospered during the Polish Golden Age, when it belonged to Hetman Jan Tarnowski (1488–1561). In the mid-16th century, its population was app. 1,200, with 200 houses located within town’s defensive wall (the wall itself had been built in the mid-15th century, and expanded in the early 16th century). In 1467, the waterworks and sewage systems were completed, with large cisterns filled with drinking water built in the main market square. In the 16th century, during the period known as the Polish Golden Age, Tarnów had a school, a synagogue, a Calvinist prayer house, Roman Catholic churches, and up to twelve guilds.

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Tarnów Cathedral preserved one of the most beautiful examples of renaissance and mannerist tomb monuments in the country.[5]

After the death of Jan Tarnowski (16 May 1561), Italian sculptor Jan Maria Padovano began creating one of the most beautiful examples of Renaissance headstones in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The monument of hetman Tarnowski is almost 14 meters tall, and stands in St. Anne Chapel, which is located in northern nave of the Tarnów Cathedral. Padovano completed his work in 1573; furthermore, he designed the Renaissance town hall, and oversaw its remodeling in the 1560s. At that time, in 28 niches of the town hall were portraits of members of the Tarnowski family - from Spicymir Leliwita to Jan Krzysztof Tarnowski, who died in 1567. In 1570 Tarnów became property of the Ostrogski family, after Zofia Tarnowska, the daughter of the hetman, married prince Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski. In 1588, after Konstanty’s death, the town changed hands several times, belonging to different families, which slowed its development. Until the Partitions of Poland, Tarnów belonged to the County of Pilzno, Sandomierz Voivodeship. The town, like almost all locations of Lesser Poland, was devastated in October 1655, during the Swedish invasion of Poland, and as a result, its population declined from 2,000 to 768. In 1723, the town became property of the Sanguszko family, which purchased it from the Lubomirski family.

Habsburg Empire

Tomb of General Józef Bem, national hero of Poland, Hungary and the former Ottoman Empire

After the first partition of Poland (1772), Tarnów was annexed by the Habsburg Empire, and remained in Austrian Galicia until late 1918. Austrian rule initially brought positive changes, as the town ceased to be private property, became the seat of a county (German: kreis), and of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tarnów (1783). On March 14, 1794, Józef Bem was born in Tarnów. In the 1830s, under the influence of events in Congress Poland (see November Uprising), Tarnów emerged as a center of Polish conspiratorial organizations. Plans for a national uprising in Galicia failed in early 1846, when local peasants began murdering the nobility in the Galician slaughter. The massacre, led by Jakub Szela (born in Smarżowa), began on February 18, 1846. Szela’s peasant units surrounded and attacked manor houses and settlements located in three counties - Sanok, Jasło, and Tarnów. The revolt got out of hand and the Austrians had to put it down.

Tarnów went through the period of quick development in the second half of the 19th century, due to the program of construction of railway system. In 1852, the town received rail connection with Kraków, due to the Galician Railway of Archduke Charles Louis, and in 1870, its population was 21,779. In 1878, gas lighting was introduced, and three years later, first daily newspaper appeared. In 1888, the Diocese Museum was founded by Rev. Jozef Baba, and in 1910, Tarnów received modern waterworks, a power plant and a new complex of the main rail station. The city remained a hotspot of Polish conspirational activities, with up to 20% of all members of the Polish Legions in World War I coming from Tarnów and its area. On November 10, 1914, units of the Russian Imperial Army captured Tarnów, and remained in the city until May 6, 1915 (see Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive). In the early stages of the offensive, Tarnów was shelled by German-Austrian heavy artillery, which brought destruction to some of its districts.

Market Square with historic and colourful tenements

Second Polish Republic

Tarnów was one of the first Polish cities to be freed during the rebirth of Poland following World War I. The Polish Legions liberated the city on the night of October 30–31, 1918. In the Second Polish Republic, Tarnów belonged to Kraków Voivodeship, and gave the newly established country many outstanding figures, such as Franciszek Latinik and Wincenty Witos. In early 1927, construction of a large chemical plant was initiated in the suburban village of Świerczków Świerczków [pl], which is now a part of the industrial borough of Mościce, a district of the city. Before the outbreak of World War II, the population of Tarnów was 40,000, of which almost half were Jewish.

1939 invasion of Poland

First transport of Polish captives deported from Tarnów to Auschwitz concentration camp during German AB-Aktion in Poland, June 1940

On August 28, 1939, a Nazi saboteur conducted the Tarnów rail station bomb attack killing 20 civilians, two days before the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany. The city was overrun by the German forces on September 7, 1939. Tarnów was incorporated into the General Government territory as the seat of the Kreishauptmanschaft Tarnow district on October 26, 1939.

On June 14, 1940, the first mass transport left the Tarnów station to Auschwitz concentration camp, with 728 Polish political prisoners. All throughout the German occupation of Poland Tarnów was an important center of the Armia Krajowa (AK) and other resistance organizations. In the mid-1944, AK’s 16th Infantry Regiment “Barbara” took part in Operation Tempest. The Wehrmacht retreated from Tarnów on January 18, 1945, and the city was captured by the Red Army.

Ludwik Solski Theatre

A few months later, the Museum of Tarnów Land was opened, and Tarnów began a postwar recovery. In 1957, State Theatre of Ludwik Solski was opened, and in 1975 Tarnów became the capital of a voivodeship.

The Jews of Tarnów

Before World War II, about 25,000 Jews lived in Tarnów.[6] Jews, whose recorded presence in the town went back to the mid-15th century, comprised about half of the town's total population. A large portion of Jewish business in Tarnów was devoted to garment and hat manufacturing. The Jewish community was ideologically diverse and included religious Hasidim, secular Zionists, and many more.[7]

Immediately following the German occupation of the city on September 8, 1939, the persecution of the Jews began. German units burned down most of the city's synagogues on September 9 and drafted Jews for forced-labor projects.[6] Tarnów was incorporated into the Generalgouvernement. Many Tarnów Jews fled to the east, while a large influx of refugees from elsewhere in occupied Poland continued to increase the town's Jewish population. In early November, the Germans ordered the establishment of a Jewish council (Judenrat) to transmit orders and regulations to the Jewish community. Among the duties of the Jewish council were enforcement of special taxation on the community and providing workers for forced labor.[7]

During 1941, life for the Jews of Tarnów became increasingly precarious.[6] The Germans imposed a large collective fine on the community. Jews were required to hand in their valuables. Roundups for labor became more frequent and killings became more commonplace and arbitrary. Deportations from Tarnów began in June 1942, when about 13,500 Jews were sent to the Belzec extermination camp. The first major act in the extermination of the Jews of Tarnów was the so-called "first operation" from 11–19 June 1942. The Germans gathered thousands of Jews in the Rynek (market place), and then they were tortured and killed. During this time period, on the streets of the town and in the Jewish cemetery, about 3,000 Jews were shot; in the woods of Zbylitowska Góra a few kilometers away from Tarnów a further 7,000 were murdered.[8] According to a document from Michal Borawski born in 1926, featured at the entry of the Bimah as part of the panel offered by the Batorego Foundation, the street stairs ("małe schody" or little stairs) from the town-center to the Bernardynski street (where the Bernardine Monastery is located), had to be cleaned of the blood by the local fire brigade for three days.[9]

Existing remains of the old synagogue

After the June deportations, the Germans forced the surviving Jews of Tarnów, along with thousands of Jews from neighboring towns, into the new Tarnów Ghetto. The ghetto was surrounded by a high wooden fence. Living conditions in the ghetto were deplorable, marked by severe food shortages, a lack of sanitary facilities, and a forced-labor regimen in factories and workshops producing goods for the German war industry. In September 1942, the Germans ordered all ghetto residents to report to Targowica Square, where they were subjected to a 'selection' in which those deemed 'non-essential' were singled out for deportation to Belzec. About 8,000 people were deported. Thereafter, deportations from Tarnów to extermination camps continued sporadically; the Germans deported a group of 2,500 in November 1942.[6]

Holocaust resistance

In the midst of the 1942 deportations, some Jews in Tarnów organized a Jewish resistance movement. Many of the resistance leaders were young Zionists involved in the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. Many of those who left the ghetto to join the partisans fighting in the forests later fell in battle with SS units. Other resisters sought to establish escape routes to Hungary, but with limited success. The Germans decided to destroy the Tarnów ghetto in September 1943. The surviving 10,000 Jews were deported, 7,000 of them to Auschwitz and 3,000 to the Plaszow concentration camp in Kraków. In late 1943, Tarnów was declared "free of Jews" (Judenrein). By the end of the war, the overwhelming majority of Tarnów Jews had been murdered by the Germans. Although 700 Jews returned in 1945, some of them soon left the city. Many moved to Israel.[6]

Geography

Tarnów lies at the Carpathian foothills, on the Dunajec and the Biała rivers. The area of the city is 72.4 square kilometres (28.0 sq mi). It is divided into sixteen districts, known in Polish as osiedla. A few kilometers west of the city lies the district of Mościce, built in the late 1920s, together with a large chemical plant. The district was named after President of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki.[3]

Climate

Tarnów is one of the warmest cities in Poland. The average temperature in January is −0.4 °C (31 °F) and 19.8 °C (68 °F) in July.[10] It is claimed that Tarnów has the longest summer in Poland spreading from mid May to mid September (above 118 days).

| Climate data for Tarnów | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) | 20.6 (69.1) | 25.1 (77.2) | 29.9 (85.8) | 32.8 (91) | 34.5 (94.1) | 36.6 (97.9) | 38.2 (100.8) | 36.8 (98.2) | 26.9 (80.4) | 22.0 (71.6) | 19.5 (67.1) | 38.2 (100.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) | 4.3 (39.7) | 8.7 (47.7) | 15.5 (59.9) | 20.5 (68.9) | 23.6 (74.5) | 25.4 (77.7) | 24.5 (76.1) | 19.4 (66.9) | 14.3 (57.7) | 8.2 (46.8) | 3.1 (37.6) | 14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) | 1.0 (33.8) | 4.6 (40.3) | 10.1 (50.2) | 14.7 (58.5) | 17.5 (63.5) | 19.8 (67.6) | 18.8 (65.8) | 14.2 (57.6) | 10.2 (50.4) | 5.3 (41.5) | 0.7 (33.3) | 9.7 (49.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) | −2.2 (28) | 0.5 (32.9) | 4.6 (40.3) | 8.9 (48) | 12.0 (53.6) | 14.2 (57.6) | 13.2 (55.8) | 9.0 (48.2) | 6.1 (43) | 2.6 (36.7) | −1.7 (28.9) | 5.4 (41.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.8 (−23.4) | −29.9 (−21.8) | −21.9 (−7.4) | −8.6 (16.5) | −3.0 (26.6) | 0.7 (33.3) | 3.8 (38.8) | 1.9 (35.4) | −4.9 (23.2) | −8.3 (17.1) | −17.1 (1.2) | −25.2 (−13.4) | −30.8 (−23.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 32 (1.26) | 31 (1.22) | 35 (1.38) | 40 (1.57) | 55 (2.17) | 77 (3.03) | 81 (3.19) | 70 (2.76) | 49 (1.93) | 43 (1.69) | 38 (1.5) | 40 (1.57) | 591 (23.27) |

| Average precipitation days | 15 | 12 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 141 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85 | 84 | 80 | 69 | 64 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 79 | 85 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 44 | 58 | 112 | 159 | 200 | 216 | 215 | 202 | 155 | 111 | 59 | 39 | 1,570 |

| Source: [1] [2] [3] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Grupa Azoty headquarters in Tarnów's industrial district Mościce

Tarnów is an important center of economy and industry. The city has chemical plants including Zakłady Azotowe w Tarnowie-Mościcach S.A., which is part of Poland's biggest company operating within the chemical sector Grupa Azoty, Becker Farby Przemysłowe Sp. z o.o., Summit Packaging Polska Sp. z o.o.; as well as food plants (Fritar), building materials (Leier Polska S.A., Bruk-Bet), textiles (Spółdzielnia "Tarnowska Odzież, Tarnospin, Tarkonfex"), and several warehouses, as well as a distribution center of the Lidl supermarket chain. Tarnów is an important center of natural gas industry, with headquarters of three different gas corporations.[3]

Another significant company based in Tarnów is the Zakłady Mechaniczne Tarnów operating in the defence industry. It manufactures handguns, assault rifles, sniper rifles and anti-air guns. It is part of the state-controlled Bumar Corporation.

Among the major shopping malls in Tarnów are the Gemini Park Tarnów and Galeria Tarnovia.

Transport

Railway station in Tarnów

Tarnów is an important road and rail hub. It lies at the intersection of two major roads - the ![]() motorway along European route E40, and the National Road nr. 73, which goes from Kielce to Jasło. Furthermore, the city is a rail junction, with four lines: three main electrified routes (westward to Kraków, eastward to Dębica and southward to Nowy Sącz), as well as secondary-importance local connection to Szczucin. The history of rail transport in Tarnów dates back to the year 1856, when the Galician Railway of Archduke Charles Louis reached the city. The architectural complex of Tarnów Main Station, fashioned after the Lviv railway station was completed in 1906 by the Austrian Partition. Since 2010, Tarnów station houses a gallery of modern art, the only such gallery located in a rail station in Poland. Tarnów also has three additional stations: Tarnów Mościce, as well as Tarnów Północny and Tarnów Klikowa, both of which are currently out of service.

motorway along European route E40, and the National Road nr. 73, which goes from Kielce to Jasło. Furthermore, the city is a rail junction, with four lines: three main electrified routes (westward to Kraków, eastward to Dębica and southward to Nowy Sącz), as well as secondary-importance local connection to Szczucin. The history of rail transport in Tarnów dates back to the year 1856, when the Galician Railway of Archduke Charles Louis reached the city. The architectural complex of Tarnów Main Station, fashioned after the Lviv railway station was completed in 1906 by the Austrian Partition. Since 2010, Tarnów station houses a gallery of modern art, the only such gallery located in a rail station in Poland. Tarnów also has three additional stations: Tarnów Mościce, as well as Tarnów Północny and Tarnów Klikowa, both of which are currently out of service.

The city's public transport system consists of 29 municipal bus routes, which provide convenient transportation to all districts. In 1911-1942 Tarnów had a tram line, with the length of 2.5 kilometres, since replaced by buses.[3]

Politics

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Tarnów constituency in 2005 included: Urszula Augustyn, PO, Edward Czesak, PiS, Aleksander Grad, PO, Barbara Marianowska, PiS, Józef Rojek, PiS, Wiesław Woda, PSL and Michał Wojtkiewicz, PiS. Member of the European Parliament elected in 2007 was Urszula Gacek, PO, EPP-ED.

Attractions

Points of interest around the city include:

- Market Square in the Old Town, with medieval urban layout of streets and tenement houses, some from the Renaissance period,

- 14th century Town Hall,

- Mikolajowski House (1524), the oldest tenement house in Tarnow,

- Remains of the Tarnowski family castle,

- Remains of the Old Synagogue,

- Remains of the 14th - 16th century defensive wall,

- 16th century two fortified towers,

- Bernadine Abbey complex,

- Late 16th century Florencki House,

- 18th and 19th century manor houses in the suburbs,

- Jewish Cemetery, founded in 1583,

- Old Cemetery (late 18th century),

- Sanguszko Palace at Gumniska,

- Railway Station (1855),

- City Park (1866),

Mausoleum of Józef Bem,- Roman Catholic churches, such as the Tarnów Cathedral (14th century, renovated in 1889-1900), and Holy Trinity church (16th century).

Education

PWST College in Tarnów

- Małopolska Wyższa Szkoła Ekonomiczna

- Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa in Tarnów (PWST)

- Wyższa Szkoła Biznesu

- John Paul II High School in Tarnów

Sports

Unia Tarnów - speedway team, championship of Poland in 2004, 2005 and 2012. Sponsored by Mościce Nitrate Factory. Also called Jaskółki (Swallows)

ZKS Unia Tarnów - Zakładowy Klub Sportowy Unia Tarnów (Workplace Sports Club United Tarnów) - Soccer team, currently in the I League in the Polska Liga 2005/2006 season.

Tarnovia Tarnów - Soccer team, also in II League in the Polska Liga 2005/2006 season.

Unia Wisła Paged Tarnów - men's basketball team, 6th in Era Basket Liga in 2003/2004 season.

Religion

Gothic Revival Church of the Holy Family

Besides Catholics other Christian denominations are also present in Tarnów including: Baptist Church, Free Brothers Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, Methodist Church, Pentecostal Church, Seventh-day Adventist Church and the non-denominational Evangelical Movement "The Lord is my Banner". Before World War II there was a large population of Jews comprising half of the city's population, but now there remain just monuments of their past presence.

According to 2007 Catholic Church statistics provided by the Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego SAC, Tarnów is the most religious city in Poland, with 72.5% of the congregation of the Diocese of Tarnów attending Mass weekly. However, as noted by the Institute director, Father Witold Zdaniewicz, the church teachings are not being followed in the area of intimacy.[11]

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Tarnów is twinned with:[12]

Trenčín in Slovakia

Trenčín in Slovakia Kiskőrös in Hungary[13]

Kiskőrös in Hungary[13] Schoten in Belgium

Schoten in Belgium Blackburn in United Kingdom

Blackburn in United Kingdom Casalmaggiore in Italy

Casalmaggiore in Italy Veszprém in Hungary

Veszprém in Hungary Nowy Sącz in Poland [14]

Nowy Sącz in Poland [14] Kotlas in Russia

Kotlas in Russia Ternopil in Ukraine

Ternopil in Ukraine Bila Tserkva in Ukraine

Bila Tserkva in Ukraine Vinnytsia in Ukraine

Vinnytsia in Ukraine

Notable residents

Józef Bem (1794–1850), general

Roman Brandstaetter (1906–1987), writer

Józef Cyrankiewicz (1911–1989), Prime Minister of Poland

Charles Denner (1926–1995), French actor

Jacek Dukaj (born 1974), writer

Ignace J(ay). Gelb (1907–1985), Polish-American ancient historian, Assyriologist

Allan Gray (born Josef Żmigród, 1902–1973), composer

Michał Heller (born 1936), philosopher- Rabbi Löb Judah ben Isaac[15]

Bartosz Kapustka (born 1996), footballer

Naphtali Keller (1834–1865), Jewish scholar; son of Israel Mendel Keller [16]- Leon Kellner (1859–?), Jewish scholar[16]

Mateusz Klich (born 1990), footballer

Tadeusz Klimecki (1895–1943), Chief of Polish General Staff

José Krakover (1883–1957), Argentinian Jewish Photographer

Andrzej Krasicki (1918–1995), film and theatre actor and theatre director

Krystyna Kuperberg (born 1944), mathematician

Siegfried Lipiner (1856–1911), Galician-Austrian Jewish poet[17]

Agata Mróz-Olszewska (1982–2008), volleyball player and two-time European Champion

Anny Ondra (1903–1987), Czech movie star

Stanisław Opałko (1911–1993), industrialist and politician- Joseph Öttinger (1818–1895), Galician-Jewish physician[18]

Tony Rickardsson (born 1970), motorcycle speedway rider, honorable resident (since June 22, 2006)

Eustachy Stanisław Sanguszko (1842–1903), nobleman, conservative politician

Wilhelm Sasnal (born 1972), painter

Jan Szczepanik (1872–1926), inventor

Jan Tarnowski (1488–1561), nobleman and Hetman

Jan of Tarnów (c.1349-1409)

Jan of Tarnów (1367–1433)

Rafał z Tarnowa (c. 1330-1373)- Rabbi Marcus Weissmann-Chajes (1830–1914), Jewish scholar[19]

- Rabbi Salo Wittmayer Baron (1895–1989), Jewish historian

Franciszek Zachara (1898–1966), composer and pianist

Notes

^ Gzyl, Krzysztof. "Tarnów / Worth seeing / Tarnow and region - Tourist Information - Polski Biegun Ciepła * Polish Hot-Spot". www.it.tarnow.pl. Retrieved 9 November 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Gzyl, Krzysztof. "Tarnów - the warmest place in Poland / Did you know that...? / Worth seeing / Tarnow and region - Tourist Information - Polski Biegun Ciepła * Polish Hot-Spot". www.it.tarnow.pl. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

^ abcde Gmina Miasta Tarnowa. "Kalendarium miasta Tarnowa". Retrieved 2016-04-01.

^ Zdzisław Spieralski, Jan Tarnowski 1488-1561, Warszawa 1977, pp. 124–125.

^ (in English) "Volume 24". The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. C. Knight. 1842. p. 66.

^ abcde "Tarnow". Ushmm.org. OTRS Ticket. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

^ ab Jewish Community in Tarnów on Virtual Shtetl, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw.

^ Adam Bartosz, In the footsteps of the Jews of Tarnów, 2007 Archived 2 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Batorego Foundation english homepage". Batory.org.pl. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

^ "TARNW, Weather History and Climate Data". Worldclimate.com. 2007-02-04. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

^ Art-4.net. "Tygodnik Katolicki - Gość Niedzielny - Wydanie Internetowe". Goscniedzielny.wiara.pl. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

^ "Miasta Partnerskie". Retrieved 1 May 2014.

^ "Testvértelepülések". Retrieved 30 April 2014.

^ "Miasta partnerskie i zaprzyjaźnione Nowego Sącza". Urząd Miasta Nowego Sącza (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

^ "Löb Judah B. Isaac". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

^ ab "Kellner, Leon". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

^ "Lipiner, Siegfried". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

^ "Öttinger, Joseph". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

^ "Weissmann-Chajes, Marcus". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tarnów. |

References

This article incorporates text from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and has been released under the GFDL as "Tarnow". OTRS ticket number.

City of Tarnów English version of Tarnów's official webpage.

Coordinates: 50°00′45″N 20°59′19″E / 50.01250°N 20.98861°E / 50.01250; 20.98861