Shankill Road bombing

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Shankill Road bombing | |

|---|---|

Part of the Troubles | |

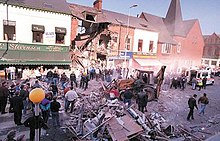

Aftermath of the bombing | |

| Location | Shankill Road, Belfast, Northern Ireland |

| Coordinates | 54°36′14″N 5°57′11″W / 54.604°N 5.953°W / 54.604; -5.953Coordinates: 54°36′14″N 5°57′11″W / 54.604°N 5.953°W / 54.604; -5.953 |

| Date | 23 October 1993 13:00 (GMT) |

| Target | UDA leadership |

Attack type | Premature explosion of time bomb |

| Deaths | 10 (including bomber) |

Non-fatal injuries | 57 |

| Perpetrator | 3rd Battalion, "A" Company, Provisional IRA Belfast Brigade |

The Shankill Road bombing was carried out by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 23 October 1993 and is one of the most notorious incidents of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The IRA aimed to assassinate the leadership of the loyalist Ulster Defence Association (UDA), who were to be meeting in a room above Frizzell's fish and chip shop on the Shankill Road, Belfast.[1][2] Two IRA members were to enter the shop disguised as deliverymen, then force the customers out at gunpoint and plant a time bomb with a short fuse. However, when the IRA members entered the shop with the bomb, it exploded prematurely. One of the IRA members was killed along with a UDA member and eight Protestant civilians.[3] More than fifty people were wounded. Unknown to the IRA, the meeting had been rescheduled.

The loyalist Shankill Road had been the location of other bomb and gun attacks, including the Balmoral Furniture Company bombing in 1971 and Bayardo Bar attack in 1975, but the 1993 bombing had the highest casualties. It also resulted in a wave of revenge attacks by loyalists, who killed 14 civilians in the week that followed, almost all of them Catholics. The deadliest attack was the Greysteel massacre.

Contents

1 Background

2 The bombing

3 Aftermath

4 Informer allegations

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Background

During the early 1990s, loyalist paramilitaries drastically increased their attacks on the Irish Catholic and Irish nationalist community and – for the first time since the beginning of the Troubles – were responsible for more deaths than republicans.[4][5] The UDA's West Belfast brigade, and its commander Johnny Adair, played a key role in this. Adair had become the group's commander in 1990.

The UDA's Shankill headquarters was above Frizzell's fish shop on the Shankill Road.[1][2] The UDA's Inner Council and West Belfast brigade regularly met there on Saturdays.[1][6][7]Peter Taylor says it was also the office of the Loyalist Prisoners' Association (LPA), and on Saturday mornings was normally crowded, as that was when money was given to prisoners' families.[8] According to Henry McDonald and Jim Cusack, the IRA had the building under surveillance for some time.[1] They say that the IRA decided to strike when one of their scouts spotted Adair entering the building on the morning of Saturday 23 October 1993.[1] Later, in a secretly-recorded conversation with police, Adair confirmed that he had been in the building that morning.[2]

The bombing

The IRA's Belfast Brigade launched an operation to assassinate the UDA's top commanders, whom it believed were at the meeting.[1][2] The plan was for two IRA members to enter the shop with a time bomb, force out the customers at gunpoint and flee before it exploded; killing those at the meeting.[1] As they believed the meeting was being held in the room above the shop, the bomb was designed to send the blast upwards. IRA members maintained that they would have warned the customers as the bomb was primed.[9] It had an eleven-second fuse, and the IRA explained that this would have allowed just enough time to clear the downstairs shop but not enough for those upstairs to escape.[6][7]

The operation would be carried out by Thomas Begley and Seán Kelly, two relatively young IRA members from Ardoyne. They drove from Ardoyne to the Shankill in a hijacked blue Ford Escort, which they parked on Berlin Street, around the corner from Frizzell's. Dressed as deliverymen, they entered the shop with the five-pound bomb in a holdall.[2] It was shortly after 1PM on a Saturday afternoon and the area was crowded with mostly women and children.[10] Whilst Kelly waited at the door, Begley made his way through the customers towards the counter, where the bomb detonated prematurely.[9] Forensic evidence showed that Begley had been holding the bomb over the refrigerated serving counter when it exploded.[11] Begley was killed along with nine other people[9]—including the owner John Frizzell, his daughter Sharon McBride, 13-year-old Leanne Murray and Michael Morrison. His common-law wife Evelyn Baird and seven-year-old daughter Michelle were also killed as was another couple, George and Gillian Williamson, and Wilma McKee.[12] The force of the blast caused the old building to collapse into a pile of rubble. The upper floor came down upon those inside the shop, crushing many of the survivors under the rubble, where they remained until rescued some hours later by volunteers and emergency services. About 57 people were injured.[6] At the scene during the rescue operation were several senior loyalists, including Adair and Billy McQuiston. The latter had been in a pub on the nearest corner when the bomb went off.[4][8] Among those rescued from the rubble was the badly-wounded Seán Kelly.[1]

Unknown to the IRA, the UDA meeting had ended early[7][2] and those attending it had left the building before the bomb exploded.[2][1] McDonald and Cusack claim that Adair and his men had stopped using the room for important meetings, allegedly because a sympathiser within the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) told Adair that the police had it bugged.[1]

Aftermath

Scene of the bombing, as of 2011

There was great anger and outrage in the Shankill in the wake of the bombing. Billy McQuiston told journalist Peter Taylor that "anybody on the Shankill Road that day, from a Boy Scout to a granny, if you'd given them a gun they would have gone out and retaliated".[8] Many Protestants saw the bombing as an indiscriminate attack on them.[6] Adair believed that the bomb was meant for him.[6] Two days after the bombing, as Adair was driving away from his house, he stopped and told a police officer "I'm away to plan a mass murder".[13] In the week following the bombing, the UDA and UVF launched a wave of "revenge attacks", killing 14 civilians.[12] The UDA shot a Catholic delivery driver in Belfast after luring him to a bogus call just a few hours after the bombing. He died on 25 October.[14] On 26 October, the UDA shot dead another two Catholic civilians and wounded five in an indiscriminate attack at a Council Depot on Kennedy Way, Belfast.[12] On 30 October, UDA members entered a pub in Greysteel frequented by Catholics and again opened-fire indiscriminately. Eight civilians (six Catholics and two Protestants) were killed and 13 were wounded. This became known as the Greysteel massacre. The UDA claimed it was a direct retaliation for the Shankill Road bombing.[4]Michael Stone and another UDA member said that Adair also vowed to launch simultaneous attacks on Catholics attending mass in Belfast. The day after the attack (Sunday), the security forces were sent to guard all Catholic churches in Belfast. A UDA member said that a carload of gunmen were sent to attack Holy Family Catholic Church on the Limestone Road, but called off the attack due to the high security.[6] Adair denied the claims.[6] The UVF shot dead a Catholic man in Newtownabbey and two Catholic brothers in Bleary.[12]

At Begley's wake, a British soldier fired upon a group of mourners standing outside Begley's home. The soldier fired twenty shots from a passing Land Rover. Among those wounded was republican activist Eddie Copeland, who needed extensive surgery. The court heard that the soldiers had been shown a photograph of Copeland before being sent on patrol. The soldier who fired the shots, Trooper Andrew Clarke, was jailed for ten years for attempted murder.[15][16] Begley was given a well-attended republican funeral in west Belfast.[17][18]Gerry Adams, president of Sinn Féin, used "unusually strong language" in condemning the bombing, saying it was wrong and could not be excused. However, he was criticised for being a pall-bearer at Begley's funeral.[10][19] David McKittrick and Eamonn Mallie wrote that if Adams had shunned the funeral it would have been "the end of him as a republican leader". They explain that it would have severely damaged his credibility within the republican movement and made it difficult for him to secure an IRA ceasefire.[20] Others, such as Taoiseach Albert Reynolds and RUC Chief Constable Hugh Annesley, agreed with this view.[21]

Seán Kelly, the surviving IRA member, was badly wounded in the blast, having lost his left eye and unable to move his left arm.[9] Upon his release from hospital, however, he was arrested and convicted of nine counts of murder, each with a corresponding life sentence. In July 2000, he was released under the terms of the Belfast Agreement.[9] In an interview shortly after his release, he said he had never intended to kill innocent people and regrets what happened.[9]

Relatives of those killed in the Shankill Road bombing adopted different positions during the 20th anniversary commemorative events in 2013.

Informer allegations

In 2016, allegations were made that the IRA commander who planned the bombing was a police informer for the RUC's Special Branch, and that he told his handlers of the planned attack. This information came from classified documents stolen by the IRA from Castlereagh RUC base in 2002.[22] IRA members believe the informer was given the go-ahead by his handlers to rig the bomb so that it exploded prematurely. They believe the goal was to cause mass civilian casualties, weakening those in the IRA who opposed a ceasefire and who wanted to continue the armed campaign.[23] Relatives of the victims asked the Police Ombudsman to investigate whether police knew about the attack before it happened.[22]

See also

- Chronology of Provisional Irish Republican Army actions (1990–99)

- Timeline of Ulster Defence Association actions

References

^ abcdefghij Henry McDonald & Jim Cusack. UDA: Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror. Penguin Ireland, 2004. pp. 247–249

^ abcdefg Dillon, Martin. The Trigger Men: Assassins and Terror Bosses in the Ireland Conflict. Random House, 2011. Part 2: Taking Down 'Mad Dog'.

^ Malcolm Sutton's Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland: 23 October 1993. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

^ abc "Johnny Adair: Feared Loyalist Leader". BBC News, 6 July 2000. Retrieved on 27 February 2007.

^ Clayton, Pamela (1996). Enemies and Passing Friends: Settler ideologies in twentieth-century Ulster. Pluto Press. p. 156.More recently, the resurgence in loyalist violence that led to their carrying out more killings than republicans from the beginning of 1992 until their ceasefire (a fact widely reported in Northern Ireland) was still described as following 'the IRA's well-tested tactic of trying to usurp the political process by violence'…

.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcdefg Wood, Ian S. Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA. Edinburgh University Press, 2006. pp.170–172

^ abc Moloney, Ed. A Secret History of the IRA. 2007 [2002]. p.415

^ abc Taylor, Peter. Loyalists. Bloomsbury Publishing, 1999. p.224.

ISBN 0-7475-4519-7

^ abcdef "Freed Shankill bomber regrets 'accident'". The Guardian, 5 August 2000. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

^ ab Oireactas debate Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

^ Connolly, Maeve. "Remembering a black week in Irish history". Irish News. 21 October 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

^ abcd Sutton, Malcolm. "CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths". cain.ulst.ac.uk.

^ David Lister, Hugh Jordan. Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and 'C Company. Random House, 2013. Chapter 8: Big Mouth.

^ David McKittrick, p.1333

^ "Leading Republican awarded almost £28,000 shooting by soldier". RTÉ News, 19 May 1999. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

^ McKittrick, p.113

^ "BBC News – UK – I only want justice says bomb victims' daughter". news.bbc.co.uk.

^ "Time". Archived from the original on 26 May 2012.

^ News Monitor for October 2001 Retrieved: 9 August 2007

^ McKittrick, p.1333

^ Taylor, Peter. Provos: The IRA and Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury Publishing, 1998. pp.338–339

^ ab "Top level agent gave information on Shankill attack". The Irish News. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

^ "Shankill Road bomb: IRA double-agent 'deliberately set device to explode prematurely'". The Independent. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

External links

- BBC interview with victim of the attack

- BBC on Johnny Adair

- BBC on Sean Kelly