Romanization of Ukrainian

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP The romanization or Latinization of Ukrainian is the representation of the Ukrainian language using Latin letters. Ukrainian is natively written in its own Ukrainian alphabet, which is based on the Cyrillic script.

Romanization may be employed to represent Ukrainian text or pronunciation for non-Ukrainian readers, on computer systems that cannot reproduce Cyrillic characters, or for typists who are not familiar with the Ukrainian keyboard layout. Methods of romanization include transliteration, representing written text, and transcription, representing the spoken word.

In contrast to romanization, there have been several historical proposals for a native Ukrainian Latin alphabet, usually based on those used by West Slavic languages, but none has caught on.

Contents

1 Romanization systems

1.1 Transliteration

1.1.1 International scholarly system

1.1.2 Library of Congress system

1.1.3 British Standard

1.1.4 BGN/PCGN

1.1.5 GOST (1971, 1983)/Derzhstandart (1995)

1.1.6 ISO 9:1995

1.1.7 Ukrainian National transliteration

1.1.8 Romanization for other languages

1.1.9 Ad hoc romanization

1.1.10 Ukrainian telegraph code

1.2 Transcription

2 Conventional romanization of proper names

3 Tables of romanization systems

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

7 External links

7.1 Transliteration systems

Romanization systems

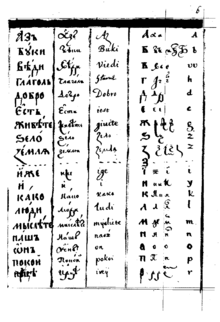

Part of a table of letters of the alphabet for the Ruthenian language, from Ivan Uzhevych's Hrammatyka Slovenskaja (1645). Columns show the letter names printed, in manuscript Cyrillic and Latin, common Cyrillic letterforms, and the Latin transliteration. Part 2, part 3.

Transliteration

Transliteration is the letter-for-letter representation of text using another writing system. Rudnyckyj classified transliteration systems into the scholarly system, used in academic and especially linguistic works, and practical systems, used in administration, journalism, in the postal system, in schools, etc.[1] The scholarly or scientific system is used internationally, with very little variation, while the various practical methods of transliteration are adapted to the orthographical conventions of other languages, like English, French, German, etc.

Depending on the purpose of the transliteration it may be necessary to be able to reconstruct the original text, or it may be preferable to have a transliteration which sounds like the original language when read aloud.

International scholarly system

- Also called scientific transliteration, this system is most often seen in linguistic publications on Slavic languages. It is purely phonemic, meaning each character represents one meaningful unit of sound, and is based on the Croatian Latin alphabet.[2] It was codified in the 1898 Prussian Instructions for libraries, or Preußische Instruktionen (PI). It was later adopted by the International Organization for Standardization, with minor differences, as ISO/R 9.

- Representing all of the necessary diacritics on computers requires Unicode, Latin-2, Latin-4, or Latin-7 encoding. Other Slavic based romanizations occasionally seen are those based on the Slovak alphabet or the Polish alphabet, which include symbols for palatalized consonants.

Library of Congress system

- The ALA-LC Romanization Tables, published by the American Library Association (1885) and Library of Congress (1905). Used to represent bibliographic information by US and Canadian libraries, by the British Library since 1975,[3] and in North American publications. The latest 1997 revision is very similar to the 1905 version.

- Requires Unicode for connecting diacritics—these are used in bibliographies and catalogues, but typically omitted in running text.

British Standard

British Standard 2979:1958, from BSI, is used by the Oxford University Press.[4] A variation is used by the British Museum and British Library, but since 1975 their new acquisitions have been catalogued using Library of Congress transliteration.[3]

BGN/PCGN

BGN/PCGN romanization is a series of standards approved by the United States Board on Geographic Names and Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use, and also adopted by the United Nations. Pronunciation is intuitive for English-speakers. Latest revision is from 1965. A modified version is also mentioned in the Oxford Style Manual.[4]- Requires only ASCII characters if optional separators are not used.

GOST (1971, 1983)/Derzhstandart (1995)

- The Soviet Union's GOST, COMECON's SEV, and Ukraine's Derzhstandart are government standards bodies of the former Eurasian communist countries. They published a series of romanization systems for Ukrainian, which were replaced by ISO 9:1995. For details, see GOST 16876-71.

ISO 9:1995

ISO 9 is a standard from the International Organization for Standardization. It supports most national Cyrillic alphabets in a single transliteration table. Each Cyrillic character is represented by exactly one unique Latin character, so the transliteration is reliably reversible. This was originally derived from the Scholarly system in 1954, and is meant to be usable by readers of most European languages.- The 1995 revision considers only graphemes and disregards phonemic differences. So, for example, г (Ukrainian He or Russian Ge) is always represented by the transliteration g; ґ (Ukrainian letter Ge) is represented by g̀.

- Representing all of the necessary diacritics on computers requires Unicode, and a few characters are rarely present in computer fonts, for example g-grave: g̀.

Ukrainian National transliteration

- The official system of Ukraine, also employed by the United Nations and many countries' foreign services, is currently widely used to represent Ukrainian geographic names, which were almost exclusively romanized from Russian before Ukrainian independence in 1991. Based on English orthography, it was codified in Decision No. 9 of the Committee on Issues of Legal Terminology on April 19, 1996.[5][6]

- The decision states that the system is binding for the transliteration of Ukrainian names in English in legislative and official acts. A new official system has been introduced for transliteration of Ukrainian personal names in Ukrainian passport in 2007.

- The system is used for transliterating all proper names (i.e. personal names in Ukrainian passports, geographical names on maps and road signs, etc.) approved as Resolution 55 of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, January 27, 2010.[7][8] This resolution brought together a unified system and modified earlier laws.

- The system requires only ASCII characters. The 27th session of the UN Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) held in New York 30 July and 10 August 2012 [9] after listening The State Agency of Land Resources of Ukraine (now known as Derzhheokadastr: Ukraine State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre)[10] experts[11] approved the Ukrainian system of romanization proper names used in official documents, in publication of cartographic works, on signs and indicators of inhabited localities, streets, stops, subway stations and other.[12]

Romanization for other languages

- Romanization intended for readers of other languages is usually transcribed phonetically into the familiar orthography. For example, y, kh, ch, sh, shch for anglophones may be transcribed j, ch, tsch, sch, schtsch for German readers (for letters й, х, ч, ш, щ). Or it may be rendered in Latin letters according to the normal orthography of another Slavic language, such as Polish or Croatian (as does the established scholarly system, above).

Ad hoc romanization

- Users of public-access computers or mobile text messaging services sometimes improvise informal romanization due to limitations in keyboard or character set. These may include both sound-alike and look-alike letter substitutions. Example: YKPAIHCbKA ABTOPKA for "УКРАЇНСЬКА АВТОРКА". See also Volapuk encoding.

- This system uses the available character set.

Ukrainian telegraph code

- For telegraph transmission. Each separate Ukrainian letter had a 1:1 equivalence to a Latin letter. Latin Q, W, V, and X are equivalent to Ukrainian Я (or sometimes Щ), В, Ж, Ь. Other letters are transcribed phonetically. This equivalency is used in building the KOI8-U table.

Transcription

Transcription is the representation of the spoken word. Phonological, or phonemic, transcription represents the phonemes, or meaningful sounds of a language, and is useful to describe the general pronunciation of a word. Phonetic transcription represents every single sound, or phone, and can be used to compare different dialects of a language. Both methods can use the same sets of symbols, but linguists usually denote phonemic transcriptions by enclosing them in slashes / ... /, while phonetic transcriptions are enclosed in square brackets [ ... ].

- IPA

- The International Phonetic Alphabet precisely represents pronunciation. Requires a special Unicode font.

Conventional romanization of proper names

In many contexts, it is common to use a modified system of transliteration that strives to be read and pronounced naturally by anglophones. Such transcriptions are also used for the surnames of people of Ukrainian ancestry in English-speaking countries (personal names have often been translated to equivalent or similar English names, e.g., "Alexander" for Oleksandr, "Terry" for Taras).

Usually such a usage is based on either the Library of Congress (in North America) or British Standard system. Such a simplified system usually omits diacritics and tie-bars, simplifies -yj and -ij word endings to "-y", ignores the Ukrainian soft sign (ь) and apostrophe (’), and may substitute ya, ye, yu, yo for ia, ie, iu, io at the beginnings of words. It may also simplify doubled letters. Unlike in the English language where an apostrophe is punctuation, in the Ukrainian language it is a letter. Therefore sometimes Rus’ is translated with an apostrophe, even when the apostrophe is dropped for all other names and words.

Conventional transliterations can reflect the history of a person or place. Many well-known spellings are based on transcriptions into another Latin alphabet, such as the German or Polish. Others are transcribed from equivalent names in other languages, for example Ukrainian Pavlo ("Paul") may be called by the Russian equivalent Pavel, Ukrainian Kyiv by the Russian equivalent Kiev.

The employment of romanization systems can become complex. For example, the English translation of Kubijovyč's Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopædia uses a modified Library of Congress (ALA-LC) system as outlined above for Ukrainian and Russian names—with the exceptions for endings or doubled consonants applying variously to personal and geographic names. For technical reasons, maps in the Encyclopedia follow different conventions. Names of persons are anglicized in the encyclopedia's text, but also presented in their original form in the index. Various geographic names are presented in their anglicized, Russian, or both Ukrainian and Polish forms, and appear in several forms in the index. Scholarly transliteration is used in linguistics articles. The Encyclopedia's explanation of its transliteration and naming convention occupies 2-1/2 pages.

Kubijovyč, Volodymyr, ed. (1963). Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopædia, Vol. 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. xxxii–xxxiv. ISBN 0-8020-3105-6.

Tables of romanization systems

| Cyrillic | Scholarly* | ALA-LC† | British‡ | BGN/PCGN** | ISO 9 | National†† | French‡‡ | German*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А а | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| Б б | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b |

| В в | v | v | v | v | v | v | v | w |

| Г г | h | h | h | h | g | h, gh¹ | h | h |

| Ґ ґ | g | g | g | g | g̀ | g | g | g |

| Д д | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d |

| Е е | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | e |

| Є є | je | i͡e | ye | ye | ê | ie, ye² | ie | je |

| Ж ж | ž | z͡h | zh | zh | ž | zh | j | sh |

| З з | z | z | z | z | z | z | z | s |

| И и | y | y | ȳ | y | i | y | y | y |

| І і | i | i | i | i | ì | i | i | i |

| Ї ї | ji (ï) | ï | yi | yi | ï | i, yi² | ï | ji |

| Й й | j | ĭ | ĭ | y | j | i, y² | y | j |

| К к | k | k | k | k | k | k | k | k |

| Л л | l | l | l | l | l | l | l | l |

| М м | m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m |

| Н н | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| О о | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| П п | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p |

| Р р | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| С с | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s, ss |

| Т т | t | t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

| У у | u | u | u | u | u | u | ou | u |

| Ф ф | f | f | f | f | f | f | f | f |

| Х х | ch | kh | kh | kh | h | kh | kh | ch |

| Ц ц | c | t͡s | ts | ts | c | ts | ts | z |

| Ч ч | č | ch | ch | ch | č | ch | tch | tsch |

| Ш ш | š | sh | sh | sh | š | sh | ch | sch |

| Щ щ | šč | shch | shch | shch | ŝ | shch | chtch | schtsch |

| Ь ь | ′ | ′ | ’, ' | ’ | ′ | – | – | – |

| Ю ю | ju | i͡u | yu | yu | û | iu, yu² | iou | ju |

| Я я | ja | i͡a | ya | ya | â | ia, ya² | ia | ja |

| ’ | - (″) | - | ”, " | ” | ’ | – | – | – |

| Historical letters | ||||||||

| Ъ ъ | ”, " | |||||||

| Ѣ ѣ | ê | |||||||

- * Scholarly transliteration

- Where two transliterations appear, the first is according to the traditional system, and the second according to ISO/R 9:1968.

- † ALA-LC

- When applied strictly, ALA-LC requires the use of two-character combining diacritics, but in practice these are often omitted.

- ‡ British Standard

- The character sequence тс = t-s, to distinguish it from ц = ts.

- Accents and diacritics may be omitted when back-transliteration is not required.

- ** BGN/PCGN

- The character sequences зг = z·h, кг = k·h, сг = s·h, тс = t·s, and цг = ts·h may be romanized with midpoints to differentiate them from the digraphs ж = zh, х = kh, ш = sh, ц = ts, and the letter sequence тш = tsh.

- †† Ukrainian National transliteration

- 1. gh is used in the romanization of зг = zgh, avoiding confusion with ж = zh.

- 2. The second variant is used at the beginning of a word.

- ‡‡ French

- Jean Girodet (1976), Dictionnaire de la langue française, Paris: Éditions Bordas.

- *** German

- (2000) Duden, v 22, Mannheim: Dudenverlag.

| Cyrillic | GOST 1971 | GOST 1986 | Derzhstandart 1995 | National 1996 | Passport 2004 | Passport 2007[13] | National 2010[7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А а | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| Б б | b | b | b | b | b | b | b |

| В в | v | v | v | v | v, w | v | v |

| Г г | g | g | gh | h, gh†† | h, g | g | h, gh†† |

| Ґ ґ | – | – | g | g | g, h | g | g |

| Д д | d | d | d | d | d | d | d |

| Е е | e | e | e | e | e | e | e |

| Є є | je | je | je | ie, ye* | ie, ye* | ie | ie, ye* |

| Ж ж | zh | ž | zh | zh | zh, j | zh | zh |

| З з | z | z | z | z | z | z | z |

| И и | i | i | y | y | y | y | y |

| І i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i |

| Ї ї | ji | i | ji | i, yi* | i, yi* | i | i, yi* |

| Й й | j | j | j† | i, y* | i, y* | i | i, y* |

| К к | k | k | k | k | k, c | k | k |

| Л л | l | l | l | l | l | l | l |

| М м | m | m | m | m | m | m | m |

| Н н | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| О о | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| П п | p | p | p | p | p | p | p |

| Р р | r | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| С с | s | s | s | s | s | s | s |

| Т т | t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

| У у | u | u | u | u | u | u | u |

| Ф ф | f | f | f | f | f | f | f |

| Х х | kh | h | kh | kh | kh | kh | kh |

| Ц ц | c | c | c | ts | ts | ts | ts |

| Ч ч | ch | č | ch | ch | ch | ch | ch |

| Ш ш | sh | š | sh | sh | sh | sh | sh |

| Щ щ | shh | šč | shh | sch | shch | shch | shch |

| Ь ь | ' | ' | j‡ | ’ | ' | – | – |

| Ю ю | ju | ju | ju | iu, yu* | iu, yu* | iu | iu, yu* |

| Я я | ja | ja | ja | ia, ya* | ia, ya* | ia | ia, ya* |

| ’ | * | " | '** | ” | – | – | – |

- * The second transliteration is used word-initially

- † Word-initially, after vowels or after the apostrophe

- ‡ After consonants

- ** Apostrophe is used before iotated ja, ju, je, ji, jo, and to distinguish the combination ьа (j'a) in compound words from я (ja), for example, Волиньавто = Volynj'avto

- †† gh is used in the romanization of зг (zgh), avoiding confusion with ж (zh)

In the National (1996) system transliteration can be rendered in a simplified form:

- Doubled consonants ж, х, ц, ч, ш are simplified, for example Запоріжжя = Zaporizhia

- Apostrophe and soft sign are omitted, but always render ьо = ’o and ьї = ’i

See also

- Cyrillic alphabets

- Cyrillic script

- Faux Cyrillic

- Romanization of Belarusian

- Romanization of Bulgarian

- Romanization of Macedonian

- Romanization of Russian

- Romanization of Serbian

- Scientific romanization of Cyrillic

- Ukrainian Latin alphabet

Notes

^ Rudnyckyj 1948, p 1.

^ [1] Transliteration Timeline on the website of the University of Arizona Library

^ ab “Searching for Cyrillic items in the catalogues of the British Library: guidelines and transliteration tables”

^ ab Oxford Style Manual (2003), “Slavonic Languages”, s 11.41.2, p 350. Oxford University Press.

^ "Official Ukrainian-English transliteration system adopted by the Ukrainian Legal Terminology Commission (in English)". Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

^ Рішення Української Комісії з питань правничої термінології (in Ukrainian)

^ ab Resolution no. 55 of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, January 27, 2010

^ Romanization system in Ukraine, paper presented on East Central and South-East Europe Division of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names

^ The 27th session of the UNGEGN materials on the UN site.

^ Держгеокадастр: Державна служба України з питань геодезії, картографії та кадастру [Derzhheokadastr: Ukraine State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre]. land.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 28 May 2016.

^ The document prepared for the UNGEGN session by Ukrainian Experts.

^ The article[dead link] about the UNGEGN 27th session on the official State of The Agency of Land Resources of Ukraine site.

^ Decision no. 858 of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, July 26, 2007

References

- Clara Beetle ed. (1949), A.L.A. Cataloging Rules for Author and Title Entries, Chicago: American Library Association, p 246.

British Standard 2979 : 1958, London: British Standards Institution.

Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems, pp. 700, 702, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.- G. Gerych (1965), Transliteration of Cyrillic Alphabets, masters thesis, Ottawa: University of Ottawa.

- Maryniak, K. (2008), 'Короткий огляд систем транслітерації з української на англійську мову' (Brief Overview of Transliteration Systems from Ukrainian to English), Захiдньоканадський збiрник — Collected Papers on Ukrainian Life in Western Canada, Part Five, Edmonton–Ostroh: Shevchenko Scientific Society in Canada, pp. 478–84.

Rudnyc’kyj, Jaroslav B. (1948). Чужомовні транслітерації українських назв: Iнтернаціональна, англійська, французька, німецька, еспанська й португальська (Foreign transliterations of Ukrainian names: The international, English, French, German, Spanish and Portuguese), Augsburg: Iнститут родо- й знаменознавства.

U.S. Board on Geographic Names, Foreign Names Committee Staff (1994). Romanization Systems and Roman-Script Spelling Conventions, p. 105.

External links

English Transliteration[permanent dead link] by the State Migration Service of Ukraine

Standard Ukrainian Transliteration — multistandard bidirectional online transliteration (BGN/PCGN, scholarly, national, ISO 9, ALA-LC, etc.) (in Ukrainian)

Ukrainian Transliteration — online Ukrainian transliteration

Ukrainian Translit — online Ukrainian transliteration service (non-standard system)

Ukrainian-Latin and Latin-Ukrainian — online transliterator (non-standard system)

Transliteration history — history of the transliteration of Slavic languages into Latin alphabets

Lingua::Translit Perl module covering a variety of writing systems. Transliteration according to several standards (e.g. ISO 9 and DIN 1460).

Transliteration systems

Transliteration of Non-Roman Scripts A collection of writing systems and transliteration tables, by Thomas T. Pedersen. PDF reference charts for many languages' transliteration systems. Ukrainian PDF

Latin transliteration — transliteration systems used for national Ukrainian domain names (in Ukrainian)

Decision No. 858 affecting transliteration of names passports (2007) (Ukrainian)

Working Group on Romanization Systems, under the United Nations Conferences on the Standardization of Geographical Names. Ukrainian PDF

ALA-LC Romanization Tables Scanned text of the 1997 edition of the ALA-LC Romanization Tables: Transliteration Schemes for Non-Roman Scripts. Ukrainian PDF

BGN/PCGN 1965 Romanization System for Ukrainian at geonames.nga.mil

Cyrillic Transliteration Table (Ukrainian and Russian), based on both International Linguistic and ALA-LC systems

Ukrainian language in the International Phonetic Alphabet (PDF, in Ukrainian)