Begging

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

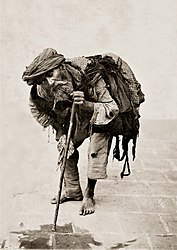

A beggar in 1880s Tehran, photographed by Antoin Sevruguin

Begging (also panhandling or mendicancy) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a beggar, panhandler, or mendicant. Street beggars may be found in public places such as transport routes, urban parks, and near busy markets. Besides money, they may also ask for food, drink, cigarettes or other small items.

Internet begging is the modern practice of asking people to give money to others over the internet, rather than in person. Internet begging is usually targeted at people who are acquainted with the beggar, but it may be advertised to strangers. Internet begging encompasses requests for help meeting basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter, as well as requests for people to pay for vacations, school trips, and other things that the beggar wants but can't comfortably afford.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Greece

1.2 Britain

1.3 In India

2 Religious begging

3 Legal restrictions

3.1 Australia

3.2 Austria

3.3 Canada

3.4 China

3.5 Denmark

3.6 Finland

3.7 France

3.8 Greece

3.9 Hungary

3.10 India

3.11 Italy

3.12 Japan

3.13 Luxembourg

3.14 Norway

3.15 Philippines

3.16 Portugal

3.17 Romania

3.18 England & Wales

3.19 United States

4 Use of funds

5 Communities reducing street begging

6 Notable beggars

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

History

Beggars have existed in human society since before the dawn of recorded history. Street begging has happened in most societies around the world, though its prevalence and exact form vary.

A beggar in Uppsala, Sweden. June 2014.

Greece

Ancient Greeks distinguished between the penes (Greek: ποινής, "active poor") and the ptochos (Greek: πτωχός, "passive poor"). The penes was somebody with a job, only not enough to make a living, while the ptochos depended on others entirely. The working poor were accorded a higher social status.[1] The New Testament contains several references to Jesus' status as the savior of the ptochos, usually translated as "the poor", considered the most wretched portion of society.

Britain

A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, vulgarly called vagabonds, was first published in 1566 by Thomas Harman. From early modern England, another example is Robert Greene in his coney-catching pamphlets, the titles of which included "The Defence of Conny-catching," in which he argued there were worse crimes to be found among "reputable" people. The Beggar's Opera is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay. The Life and Adventures of Bampfylde Moore Carew was first published in 1745. There are similar writers for many European countries in the early modern period.[citation needed]

According to Jackson J. Spielvogel, "Poverty was a highly visible problem in the eighteenth century, both in cities and in the countryside... Beggars in Bologna were estimated at 25 percent of the population; in Mainz, figures indicate that 30 percent of the people were beggars or prostitutes... In France and Britain by the end of the century, an estimated 10 percent of the people depended on charity or begging for their food."[2]

The British Poor Laws, dating from the Renaissance, placed various restrictions on begging. At various times, begging was restricted to the disabled. This system developed into the workhouse, a state-operated institution where those unable to obtain other employment were forced to work in often grim conditions in exchange for a small amount of food. The welfare state of the 20th century greatly reduced the number of beggars by directly providing for the basic necessities of the poor from state funds.

In India

A street beggar in India gets into a car

Beggary is an age old social phenomenon in India. In the medieval and earlier times begging was considered to be an acceptable occupation which was embraced within the traditional social structure.[3] This system of begging and alms-giving to mendicants and the poor is still widely practiced in India, with over 400,000 beggars in 2015.[4]

In contemporary India, beggars are often stigmatized as undeserving. People often believe that beggars are not destitute and instead call them professional beggars.[vague][5][better source needed] There is a wide perception of begging scams.[6] This view is refuted by grassroots research organizations such as Aashray Adhikar Abhiyan, which claim that beggars and other homeless people are overwhelmingly destitute and vulnerable. Their studies indicate that 99 percent men and 97 percent women resort to beggary due to abject poverty, distress migration from rural villages and the unavailability of employment.[7]

Religious begging

A mendicant outside ‘Kalkaji Mandir’ in Delhi, India

Many religions have prescribed begging as the only acceptable means of support for certain classes of adherents, including Hinduism, Sufism, Buddhism, and typically to provide a way for certain adherents to focus exclusively on spiritual development without the possibility of becoming caught up in worldly affairs.

Religious ideals of ‘Bhiksha’ in Hinduism ,‘Charity’ in Christianity besides others promote alms-giving.[8] This obligation of making gifts to God by alms-giving explains the occurrence of generous donations outside religious sites like temples and mosques to mendicants begging in the name of God.

Tzedakah plays a central role in Judaism. According to the Torah, Jews are obligated to contribute 10% of their income as tithes, which also can include giving to the poor.

In Buddhism, monks and nuns traditionally live by begging for alms, as did the historical Gautama Buddha himself. This is, among other reasons, so that lay people can gain religious merit by giving food, medicines, and other essential items to the monks. The monks seldom need to plead for food; in villages and towns throughout modern Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and other Buddhist countries, householders can often be found at dawn every morning streaming down the road to the local temple to give food to the monks. In East Asia, monks and nuns were expected to farm or work for returns to feed themselves.[9][10][11]

Legal restrictions

A kindness meter in downtown Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The meter accepts donations for charitable efforts to help the poor as part of an official effort to discourage panhandling.

Begging has been restricted or prohibited at various times and for various reasons, typically revolving around a desire to preserve public order or to induce people to work rather than to beg for economic or moral reasons. Various European poor laws prohibited or regulated begging from the Renaissance to modern times, with varying levels of effectiveness and enforcement. Similar laws were adopted by many developing countries such as India.

"Aggressive panhandling" has been specifically prohibited by law in various jurisdictions in the United States and Canada, typically defined as persistent or intimidating begging.[12]

Australia

Each State and Territory has individual laws regarding begging and panhandling.

In South Australia, begging for alms is illegal, and may bring a maximum penalty of $250. This legislation is outlined in the Summary Offences Act 1953 - Section 12 [13]

Austria

There is no nationwide ban but it is illegal in several federal states.[14]

Canada

The province of Ontario introduced its Safe Streets Act in 1999 to restrict specific kinds of begging, particularly certain narrowly defined cases of "aggressive" or abusive begging.[15] In 2001 this law survived a court challenge under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[16] The law was further upheld by the Court of Appeal for Ontario in January 2007.[17]

One response to the anti-panhandling laws which were passed was the creation of the Ottawa Panhandlers Union which fights for the political rights of panhandlers. The union is a shop of the Industrial Workers of the World.

British Columbia enacted its own Safe Streets Act in 2004 which resembles the Ontario law. There are also critics in that province who oppose such laws.[18]

China

Begging in China is illegal if:

- Coercing, decoying or utilizing others to beg;

- Forcing others to beg, repeatedly tangling or using other means of nuisance.

Those cases are violations of the Article 41 of the Public Security Administration Punishment Law of the People's Republic of China. For the first case, offenders would receive a detention between 10 days and 15 days, with an additional fine under RMB 1,000; for the second case, it is punishable by a 5-day detention or warning.

According to Article 262(2) or the Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China, organizing disabled or children under 14 to beg is illegal and will be punished by up to 7 years in prison, and fined.

Denmark

Begging in Denmark is illegal under section 197 of the penal code. Begging or letting a member of your household under 18 beg is illegal after being warned by the police and is punishable by 6 months in jail.[14][19]

Finland

Begging has been legal in Finland since 1987 when the poor law was invalidated. In 2003, the Public Order Act replaced any local government rules and completely decriminalized begging.[20]

France

Louis Dewis, "The Old Beggar", Bordeaux, France, 1916

A law against begging ended in 1994 but begging with aggressive animals or children is still outlawed.[14]

Greece

A woman begging at traffic lights in Patras, Greece.

Under article 407 of the Greek Penal Code, begging was punishable by up to 6 months in jail and up to a 3000 euro fine. However, this law was repelled in November 2018, after protests from street musicians in the city of Thessaloniki. [14]

Hungary

Hungary has a nationwide ban. This may include stricter related laws in cities such as Budapest, which prohibits picking things from rubbish bins.[14]

India

Begging is criminalized in cities such as Mumbai and Delhi as per the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, BPBA (1959).[21] Under this law, officials of the Social Welfare Department assisted by the police, conduct raids to pick up beggars who they then try in special courts called ‘beggar courts’. If convicted, they are sent to certified institutions called ‘beggar homes’ also known as ‘Sewa Kutir’ for a period ranging from one to ten years for detention, training and employment. The government of Delhi, besides criminalizing alms-seeking has also criminalized alms-giving on traffic signals to reduce the ‘nuisance’ of begging and ensure the smooth flow of traffic.

Aashray Adhikar Abhiyan and People's Union of Civil Liberties, PUCL have critiqued this Act and advocated for its repeal.[22] Section 2(1) of the BPBA broadly defines ‘beggars’ as those individuals who directly solicit alms as well as those who have no visible means of subsistence and are found wandering around as beggars. Therefore, during the implementation of this law the homeless are often mistaken as beggars.[7] Beggar homes, which are meant to provide vocational training, have been often found to have abysmal living conditions.[22]

Italy

Begging with children or animals is forbidden but the law is not enforced.[14]

Japan

Buddhist monks appear in public when begging for alms.[23] Although homelessness in Japan is common, such people rarely beg.

Luxembourg

Begging in Luxembourg is legal except when it is indulged in as a group or the beggar is a part of an organised effort. According to Chachipe a Roma rights advocacy NGO 1639 begging cases were reported by Luxembourgian law enforcement authorities. Roma beggars were arrested, handcuffed, taken to police stations and held for hours and had their money confiscated.[24]

Norway

Begging is banned in some counties and there were plans for a nationwide ban in 2015, however this was dropped after the Centre Party withdrew their support.[14]

The Singing Beggars by Russian painter Ivan Yermenyov c. 1775

Philippines

Begging is prohibited in the Philippines under the Anti-Mendicancy Law of 1978 although this is not strictly enforced.[25]

Portugal

In Portugal, panhandlers normally beg in front of Catholic churches, at traffic lights or on special places in Lisbon or Oporto downtowns. Begging is not illegal in Portugal. Many social and religious institutions support homeless people and panhandlers and the Portuguese Social Security normally gives them a survival monetary subsidy.

Romania

Law 61 of 1991 forbids the persistent call for the mercy of the public, by a person who is able to work.[26]

US State Department Human Rights reports note a pattern of Roma children registered for "vagrancy and begging".[27]

In a 1786 James Gillray caricature, the plentiful money bags handed to King George III are contrasted with the beggar whose legs and arms were amputated, in the left corner

England & Wales

Begging is illegal under the Vagrancy Act of 1824. However it does not carry a jail sentence and is not well enforced in many cities,[28] although since the Act applies in all public places it is enforced more frequently on public transport.

United States

In parts of San Francisco, California, aggressive panhandling is prohibited.[29]

In May 2010, police in the city of Boston started cracking down on panhandling in the streets in downtown, and were conducting an educational outreach to residents advising them not to give to panhandlers. The Boston police distinguished active solicitation, or aggressive panhandling, versus passive panhandling of which an example is opening doors at a store with a cup in hand but saying nothing.[30]

U. S. Courts have repeatedly ruled that begging is protected by the First Amendment's free speech provisions. On August 14, 2013, the U. S. Court of Appeals struck down a Grand Rapids, Michigan anti-begging law on free speech grounds.[31] An Arcata, California law banning panhandling within twenty feet of stores was struck down on similar grounds in 2012.[32]

Use of funds

A beggar in Denver, USA in 2018.

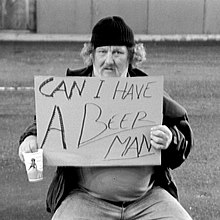

A man holding a sign using self-deprecating humor for begging

A 2002 study of 54 panhandlers in Toronto reported that of a median monthly income of $638 Canadian dollars (CAD), those interviewed spent a median of $200 CAD on food and $192 CAD on alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs, according to

Income and spending patterns among panhandlers, by Rohit Bose and Stephen W. Hwang.[33] The Fraser Institute criticized this study, citing problems with potential exclusion of lucrative forms of begging and the unreliability of reports from the panhandlers who were polled in the Bose/Hwang study.[34]

In North America, panhandling money is widely reported to support substance abuse and other addictions. For example, outreach workers in downtown Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, surveyed that city's panhandling community and determined that approximately three-quarters use some of the donated money to buy tobacco products, while two-thirds buy solvents or alcohol.[35] In Midtown Manhattan, one outreach worker anecdotally commented to the New York Times that substance abuse accounts for 90 percent of panhandling funds.[36] This, too, may not be representative since outreach workers work with those with abuse problems.[citation needed]

Communities reducing street begging

Please do not Encourage the Beggars Sarahan, India

Because of concerns that people begging on the street may use the money to support alcohol or drug abuse, some advise those wishing to give to beggars to give gift cards or vouchers for food or services, and not cash.[35][37][38][39][40][41] Some shelters also offer business cards with information on the shelter's location and services, which can be given in lieu of cash.[42] This has been criticised since there are typically far fewer shelter beds than people in need.

"The Man with the Twisted Lip", illustrated by Sidney Paget, a beggar playing a major role in a Sherlock Holmes adventure.

Notable beggars

Bampfylde Moore Carew, self-styled King of the Beggars- Diogenes of Sinope

Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism accepted alms from people to survive[43]- Gavroche Thenardier in Victor Hugo's Les Misérables

- Lazarus

- Nicholas Jennings in Thomas Harman's Caveat for Common Cursitors

So Chan, Chinese folk hero of Drunken Fist

Dobri Dobrev, Bulgarian ascetic and philanthropist

See also

- Begging behavior in animals

- Begging letter

- Belisarius

- Busking

- Child Begging

- Fundraising

- Garbage picking

- Mendicant Orders

- Street fundraising

References

^ Cavallo, Guglielmo (1997). The Byzantines. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-226-09792-3..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Jackson J. Spielvogel (2008). "Western Civilization: Since 1500". Cengage Learning. p.566.

ISBN 0-495-50287-1

^ Pande, B.B (1983). "The Administration of Beggary Prevention Laws in India: a legal aid viewpoint". 11. International Journal of the Sociology of Law: 291–304.

^ "Over 4 Lakh Beggars in India, West Bengal Tops the List Among States".

^ "6 Professional Beggars In India Who Are Probably Richer Than You & I". 2015-07-25.

^ "India Beggars and Begging Scams: What You Should Know".

^ ab AAA, Ashray Adhikar Abhiyan (2006). People Without A Nation: the destituted people; A documented outcome of the national consultation on Urban Poor: Special Focus on Beggary and Vagrancy Laws- the issue of De-custodialisation (De-criminalization). Print-O-Graph, New Delhi. p. 8.

^ Gopalakrishnan, A. (2002). "Poverty As Crime". Frontline Magazine. 19: 23.

^ "農禪vs商禪" (in Chinese). Blog.udn.com. 2009-08-19. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

^ "僧俗". 2007.tibetmagazine.net. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

^ "鐵鞋踏破心無礙 濁汗成泥意志堅——記山東博山正覺寺仁達法師". Hkbuddhist.org. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

^ Johnny Johnson (November 3, 2008). "In tough times, panhandling may increase in Oklahoma City". The Oklahoman.

^ "Summary Offences Act 1953 - Sect. 12". South Australian Government. Australia. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

^ abcdefg "(swedish) I Haag stoppade man tiggarna med förbud". Sveriges Television.

^ "Safe Streets Act". Government of Ontario. 1999. Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ "'Squeegee kids' law upheld in Ontario". CBC News. 2001-08-03. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ "Squeegee panhandling washed out by Ontario Appeal Court". CBC News. 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

^ "Police chief welcomes Safe Streets Act". CBC News. 2004-10-26. Archived from the original on 2007-05-10. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ "Straffeloven kap. 22" (in Danish). Archived from the original on 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2014-11-09.

^ "Authorities powerless to act against beggars with children in tow". Helsingin Sanomat.

^ "The Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959" (PDF).

^ ab "Criminalizing Poverty".

^ "The Zen - Teaching of Mu". Japan National Tourist Organisation. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

^ Groth, Annette (2012-06-01). "The situation of Roma in Europe: movement and migration" (PDF). Council of Europe: Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

^ Borromeo, Rene (16 December 2013). "Should you give to beggars? Cebu City's Anti-Mendicancy Campaign" (in Cebuano and English). Cebu: The Freeman. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

^ "Legea nr. 61/1991 (republicata 2011)" (in Romanian). Poliția de Proximitate. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2006-03-08). "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 (Romania)". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on September 19, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ Bunyan, Nigel (2003-08-22). "Beggar ban may spark nationwide crackdown". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

^ Debate Continues Over Proposed Sit-Lie Ordinance, KTVU, 10 March 2010

^ Schuler, Melina, "Cops Planning to Combat Panhandling", The Boston Courant, May 14–20 issue, 2010. "Aggressive solicitation is against the law and is defined as an action that is likely to cause a reasonable person to fear harm or to intimidate him or her into compliance, Ivens said. Passive panhandling, like in front of a convenience store, is constitutionally allowed, however, it is a violation of a Boston ordinance to do it within 10 feet [3 m] of an ATM, bank, or check cashing business during hours of operation, [Boston Police Captain Paul] Ivens said."

^ John Agar, "Michigan's begging law violates First Amendment: federal appeals court" mlive.com

^ Romney, Lee (September 27, 2012). "Arcata panhandling law mostly struck down by judge: A Humboldt County judge says provisions of the ordinance banning non-aggressive panhandling within 20 feet of stores, intersections, parking lots and bus stops are unconstitutional". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

^ Bose, Rohit & Hwang, Stephen W. (2002-09-03). "Income and spending patterns among panhandlers". 167 (5). Canadian Medical Association Journal. pp. 477–479. PMC 121964.

^ "Begging for Data". Canstats. 3 September 2002. Archived from the original on 20 April 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ ab ""Change for the Better" fact sheet" (PDF). Downtown Winnipeg Biz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ Tierney, John (1999-12-04). "The Big City; The Handout That's No Help To the Needy". The New York Times. p. B1. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

^ Wahlstedt, Eero. "Evaluation study of the Oxford Begging Initiative". Oxford City Council. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

^ Johnsen & Fitzpatrick, S. & S. (2010). "Revanchist Sanitisation or Coercive Care? The Use of Enforcement to Combat Begging, Street Drinking and Rough Sleeping in England". Urban Studies. 47 (8): 1703–1723. doi:10.1177/0042098009356128. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

^ Hermer, J. (1999). Policing compassion: 'Diverted Giving' on the Winchester High Street. Bristol: The Policy Press. ISBN 978-1861341556. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

^ "Real Change, not Spare Change". Portland Business Alliance. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

^ Dromi, Shai M. (2012). "Penny for your Thoughts: Beggars and the Exercise of Morality in Daily Life". Sociological Forum. 27 (4): 847–871. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01359.x.

^ Peace Studies Program. "Homelessness Contact Cards". George Washington University. Archived from the original on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

^ "Begging Bowl - Buddhist Things". ReligionFacts. Archived from the original on 2011-12-05. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

Further reading

- Karash, Robert L., "Spare Change?", Spare Change News, March 25, 2010.

- Malanga, Steven, The Professional Panhandling Plague, City Journal, v.18, n.3, Summer 2008, The Manhattan Institute, New York, NY.

- Sandage, Scott A., Born Losers: A History of Failure in America, Harvard University Press, 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Begging. |

| Look up begging, spanging, panhandling, or mendicancy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Begging. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article mendicancy. |

Rooney, Emily, "Panhandling — Public Nuisance Or Basic Right?", The Emily Rooney Show, WGBH-FM Radio, Boston, Tuesday, June 5, 2012. Guests: Vincent Flanagan, Executive Director of Homeless Empowerment Project Spare Change News; Robert Haas, Cambridge Police Commissioner; Denise Jillson, President of the Harvard Square Business Association

Selected legal cases on panhandling in the United States, University of Albany Center for Problem Oriented Policing.