Ultimate (sport)

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| |

| Highest governing body | World Flying Disc Federation |

|---|---|

| Nicknames |

|

| Characteristics | |

| Team members | Grass: 7/team; indoor: 5/team; beach: 5/team (sometimes fewer or more) |

| Mixed gender | In some competitions and most leagues |

| Equipment | Flying disc (disc, frisbee) |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Recognized by International Olympic Committee;[1][2] eligible for 2024 Olympics.[3] |

| World Games | 1989 (invitational), 2001 – present[3] |

Ultimate, originally known as Ultimate frisbee, is a non-contact team sport played with a flying disc (frisbee). Ultimate was developed in 1968 by a group of students at Columbia High School in Maplewood, New Jersey. Although Ultimate resembles many traditional sports in its athletic requirements, it is unlike most sports due to its focus on self-officiating, even at the highest levels of competition.[4] The term frisbee, often used to generically describe all flying discs, is a registered trademark of the Wham-O toy company, and thus the sport is not formally called "Ultimate frisbee", though this name is still in common casual use. Points are scored by passing the disc to a teammate in the opposing end zone. Other basic rules are that players must not take steps while holding the disc, and interceptions, incomplete passes, and passes out of bounds are turnovers. Rain, wind, or occasionally other adversities can make for a testing match with rapid turnovers, heightening the pressure of play.

From its beginnings in the American counterculture of the late 1960s, ultimate has resisted empowering any referee with rule enforcement. Instead it relies on the sportsmanship of players and invokes "Spirit of the Game" to maintain fair play.[5] Players call their own fouls, and dispute a foul only when they genuinely believe it did not occur. Playing without referees is the norm for league play but has been supplanted in club competition by the use of "observers" or "game advisors" to help in disputes, and the professional league employs empowered referees.

In 2012, there were 5.1 million Ultimate players in the United States.[6] Ultimate is played across the world in pickup games and by recreational, school, club, professional, and national teams at various age levels and with open, women's, and mixed divisions.

The United States wins most of the world titles, but not all of them. US teams won 4 out of 5 divisions in 2014 world championship,[7][clarification needed] and all divisions in 2016 competitions between national teams [2][3] (both grass). USA won the 2017 beach world championships, but the Russian women's team ended the American previous undefeated streak by defeating team USA in the women's final[8] (US teams won the other six divisions).[9]

Contents

1 Invention and history

2 Players associations

3 Rules

3.1 Rulebooks: USAU (North America) WFDF (world wide) AUDL (NA pro league)

3.1.1 AUDL rule changes

4 Throwing and catching techniques

5 Strategy and tactics

5.1 Offense

5.1.1 Handlers and cutters

5.1.2 Vertical stack

5.1.3 Horizontal stack

5.1.4 Feature, German, or isolation

5.1.5 Hexagon or Mexican

5.2 Defense

5.2.1 Pull

5.2.2 Force

5.2.3 Man-to-man

5.2.4 Zonal

5.2.4.1 Cup

5.2.4.2 Wall

5.2.5 Junk or clam

5.2.6 Hexagon or flexagon

6 Spirit of the game

7 Competitions

7.1 Professional league – AUDL

7.2 North American leagues

7.3 College teams

7.4 National teams

7.5 Hat tournaments

8 Common concepts and terms

9 See also

10 References

11 External links

Invention and history

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

I just remember one time running for a pass and leaping up in the air and just feeling the Frisbee making it into my hand and feeling the perfect synchrony and the joy of the moment, and as I landed I said to myself, 'This is the ultimate game. This is the ultimate game.'

— Jared Kass, one of the inventors of ultimate, interviewed in 2003, speaking of the summer of 1968[10]

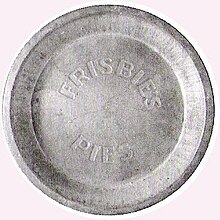

Team flying disc games using pie tins and cake pan lids were part of Amherst College student culture for decades before plastic discs were available. A similar two-hand, touch-football-based game was played at Kenyon College in Ohio starting in 1942.[10]

Frisbie pie tin

From 1965 or 1966 Jared Kass and fellow Amherst students Bob Fein, Richard Jacobson, Robert Marblestone, Steve Ward, Fred Hoxie, Gordon Murray, and others evolved a team frisbee game based on concepts from American football, basketball, and soccer. This game had some of the basics of modern Ultimate including scoring by passing over a goal line, advancing the disc by passing, no travelling with the disc, and turnovers on interception or incomplete pass. Jared, an instructor and dorm advisor, taught this game to high school student Joel Silver during the summer of 1967 or 1968 at Mount Hermon Prep school summer camp.

Joel Silver, along with fellow students Jonny Hines, Buzzy Hellring, and others, further developed Ultimate beginning in 1968 at Columbia High School, Maplewood, New Jersey, USA (CHS). The first sanctioned game was played at CHS in 1968 between the student council and the student newspaper staff. Beginning the following year evening games were played in the glow of mercury-vapor lights on the school's student-designated parking lot. Initially players of Ultimate frisbee (as it was known at the time) used a "Master" disc marketed by Wham-O, based on Fred Morrison's inspired "Pluto Platter" design. Hellring, Silver, and Hines developed the first and second edition of "Rules of Ultimate Frisbee". In 1970 CHS defeated Millburn High 43–10 in the first interscholastic Ultimate game. CHS, Millburn, and three other New Jersey high schools made up the first conference of Ultimate teams beginning in 1971.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

Alumni of that first league took the game to their colleges and universities. Rutgers defeated Princeton 29–27 in 1972 in the first intercollegiate game. This game was played exactly 103 years after the first intercollegiate American football game by the same teams at precisely the same site, which had been paved as a parking lot in the interim. Rutgers won both games by an identical margin.[12]

Rutgers also won the first ultimate frisbee tournament in 1975, hosted by Yale, with 8 college teams participating. That summer ultimate was introduced at the Second World Frisbee Championships at the Rose Bowl. This event introduced ultimate on the west coast of the USA.[12]

In 1975, ultimate was introduced at the Canadian Open Frisbee Championships in Toronto as a showcase event.[16] Ultimate league play in Canada began in Toronto in 1979.[17] The Toronto Ultimate Club is one of ultimate's oldest leagues.[18]

In January 1977 Wham-O introduced the World Class "80 Mold" 165 gram frisbee. This disc quickly replaced the relatively light and flimsy Master frisbee with much improved stability and consistency of throws even in windy conditions. Throws like the flick and hammer were possible with greater control and accuracy with this sturdier disc. The 80 Mold was used in Ultimate tournaments even after it was discontinued in 1983.[19]

Discraft, founded in the late 1970s by Jim Kenner in London, Ontario, later moved the company from Canada to its present location in Wixom, Michigan.[20] Discraft introduced the Ultrastar 175 gram disc in 1981, with an updated mold in 1983. This disc was adopted as the standard for ultimate during the 1980s, with Wham-O holdouts frustrated by the discontinuation of the 80 mold and plastic quality problems with discs made on the replacement 80e mold.[21] Wham-O soon introduced a contending 175 gram disc, the U-Max, that also suffered from quality problems and was never widely popular for ultimate. In 1991 the Ultrastar was specified as the official disc for UPA tournament play and remains in wide use.[19][22][23]

The popularity of the sport spread quickly, taking hold as a free-spirited alternative to traditional organized sports. In recent years college ultimate has attracted a greater number of traditional athletes, raising the level of competition and athleticism and providing a challenge to its laid back, free-spirited roots.[24]

In 2010, Anne Watson, a Vermont teacher and Ultimate coach, launched a seven-year effort to have Ultimate Frisbee recognized as full varsity sport in the state's high schools.[25][26] Watson's effort culminated on November 3, 2017, when the Vermont Principals Association, which oversees the state's high school sports programs, unanimously approved Ultimate Frisbee as a varsity sport beginning in the Spring 2019 season.[25][27] The approval made Vermont the first U.S. state to recognize Ultimate Frisbee as a varsity sport.[25][27]

Players associations

In late December 1979, the first national player-run ultimate organization was founded in the United States as the Ultimate Players Association (UPA). Tom Kennedy was elected its first director. Before the UPA, events had been sponsored by the International Frisbee Association (IFA), a promotional arm of Wham-O.[12]

The UPA organized regional tournaments and has crowned a national champion every year since 1979. Glassboro State College defeated the Santa Barbara Condors 19–18 at the first UPA Nationals in 1979.[12]

In 2010, the UPA rebranded itself as USA Ultimate.

The first European Championship tournament for national teams was held in 1980 in Paris. Finland won, with England and Sweden finishing second and third.[12] In 1981 the European Flying Disc Federation (EFDF) was formed.[12] In 1984 the World Flying Disc Federation was formed by the EFDF to be the international governing body for disc sports.[12] The first World Championships tournament was held in 1983 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

The European Ultimate Federation is the governing body for the sport of Ultimate in Europe. Funded in 2009, it is part of the European Flying Disc Federation (EFDF) and of the World Flying Disc Federation.

Ultimate Canada, the national governing body in Canada, was formed in 1993. The first Canadian National Ultimate Championships were held in Ottawa 1987.[28]

In 2006, ultimate became a BUCS accredited sport at Australian and UK universities for both indoor and outdoor open division events. In 2012, Robert Knight captained Australia's National Frisbee team to the World Championship Final, coining a tactic now popularly referred to as the "reverse-double-double cheese stack", and inspiring a huge grass roots following.

The WFDF was granted full IOC recognition on 2 Aug 2015.[29] This allows the possibility for the organization to receive IOC funding and become an Olympic Game.[30]

Rules

Ultimate playing field

A point is scored when one team catches the disc in the opposing team's end zone.

Each point begins with both teams lining up on the front of their respective end zone line. A player cannot run with the disc—it may be moved only by passing. The defense throws ("pulls") the disc to the offense. A regulation grass outdoor game has seven players per team, but 5-6 player games are common. In ultimate, there is no concept of intentional vs. unintentional fouls: infractions are called by the players themselves and resolved in such a way as to minimise the impact of such calls on the outcome of the play (sometimes resulting in "do-overs" where the disc is returned to the last uncontested possession), rather than emphasizing penalties or "win-at-all-costs" behaviour. The integrity of ultimate depends on each player's responsibility to uphold the spirit of the game.

The player holding the disc establishes a pivot point (i.e. they cannot run with the disc, just step out from a single point). The disc is advanced by throwing it to team-mates.

If a pass is incomplete, it is a "turnover" and the opposing team immediately gains possession, playing to score in the opposite direction. Passes are incomplete if they are caught by a defender, touch the ground (meaning defenders need only knock the disc out of the air to gain possession), or touch an out-of-bounds object (including the ground, or an out-of-bounds player). However, if a player jumps from in bounds, catches and then throws the disc while in the air and technically out of bounds, the disc is still in play and can be caught or defended by players on the field. This feat of athleticism and precision is highly praised, and dubbed "Greatest."

Ultimate is non-contact, meaning non-incidental (play-affecting or dangerous) physical contact is disallowed. Defenders cannot take the disc from an offensive player who has secured a catch (this is known as a strip). Non-incidental contact is a foul, regardless of intent, with various consequences depending on the situation and the league rules. Incidental contact, like minor collisions while jumping for the disc or running for it can be acceptable, depending on the circumstances. Parameters like who has the "right" for the relevant space, who got the disc etc. will determine whether a foul has been committed or not. Attitudes can vary between leagues and countries, even if the letter of the rule remains the same.

Contact is also disallowed for the defender marking the offense player with the disc, and there are further restrictions on positions this defender can take in order to minimise incidental contact.[31]

Defending against the person who has the disc is a central part of the defensive strategy (colloquially "marking"). The defensive "marker" counts aloud to 10 seconds, which is referred to as "stalling". If the disc has not been thrown when the defending player reaches 10, it is turned over to the other team. "Stall" can be only be called after the defender has actually counted the 10 seconds.[32] There can only be one player defending in a 3-meter radius around the person who has the disc unless that player is defending against another offensive player. The marker must stay one disc's diameter away from the thrower and must not wrap their hands around the thrower, or the person with the disc can call a foul ("wrapping").

Ultimate is predominantly self-refereed, relying on the on-field players to call their own infractions and to try their best to play within the rules of the game. It is assumed that players will not intentionally violate the rules and will be honest when discussing foul calls with opponents. This is called Spirit of the Game.[5] After a call is made, the players should agree on an outcome, based on what they think happened and how the rules apply to that situation. If players cannot come to agreement on the call's validity, the disc can be given back to the last uncontested thrower, with play restarting as if before the disputed throw.

Each point begins with the two teams starting in opposite end zones. The team who scored the previous point are now on defense. The teams indicate their readiness by raising a hand, and the team on defense will throw the disc to the other team. This throw is called a "pull". When the pull is released, all players are free to leave their end zones and occupy any area on the field. Both teams should not leave the endzone before the pull is released. Thus, the defending team must run most of the field length at speed to defend immediately. And a good pull is designed to hang in the air as long as possible to give the defending team time to make the run.

A regulation outdoor game is played 7 vs. 7, with substitutions allowed between points and for injuries. Games are typically played to a points limit of 13/15/17 and/or a time limit of 75/90/100 minutes. There is usually a halftime break and an allowance of a 2 timeouts per team each half.[33][34]

A WFDF [35] regulation field is 100 meters by 37 meters, including end zones each 18 meters deep.[36] As of 2016, a USA Ultimate regulation field for all divisions has been changed to match that of the WFDF by way of an "experimental rule".[31]

Competitive ultimate is played in gender divisions using gender determination rules based on those of the IOC.[37] Different competitions may have a "men's" or an "open" division (the latter usually being extremely male-dominated at competitive levels, but technically unrestricted). Mixed is officially played with 4 of one gender and 3 of the other, but variants exist for different numbers. Men's, women's, and mixed ultimate are played by the same rules besides those explicitly dealing with gender restrictions.

Rulebooks: USAU (North America) WFDF (world wide) AUDL (NA pro league)

Some rules vary between North America and the rest of the world.

More significant rule changes were made in the AUDL pro league games.

Most differences are minor and they can can be found online.[38] USAU rules have been slowly shifting toward WFDF compatibility.

AUDL rule changes

American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL), the semi-professional ultimate league with teams in the U.S. and Canada, has its own variant of the rules, and has made multiple rule changes in recent years. Some of the more important include:[39]

- Slightly larger field sizes

- Shorter end zone

- In WFDF, games are played to X points with two halves and global time caps. In AUDL, The game is played in four quarters of 12:00 minutes each. The counted times is only when the disc is in actual play, resulting in games lasting for over two hours at times. The game stops on the timed second, rather than until the end of the point.

This precise cut-off has resulted in adapted strategies for the final seconds of the quarters or games. - Referees making calls instead of players. But players can overrule the referees when the players call is against their own team. Its called the integrity rule, as players will call a foul against themselves even when the referee deemed it not to be a foul and so on.

- Most fouls are penalized automatically by the referee with a 10 yard move of position against the fouling team.

- Double team is allowed in defense, but not triple team.

- Stall count is 7 seconds instead of 10 seconds

- Stall count is counted by the referees with a stopwatch, in silence. The players has to figure the time on his own.

Throwing and catching techniques

A player may catch the disc with one or two hands. A catch can grab the rim, or simultaneously grab the top and bottom of the frisbee – in a clap-catch / "pancake catch". Care is needed with the hand placement when catching with one hand on the disc rim, making sure to catch on the proper side of the disc, according to which way the disc is spinning. When a frisbee is thrown at high speeds, as is frequently the case in a competitive game of ultimate, one side of the disc can spin out of the player's hand, and the other side can spin into their hand, which can make a catch far more secure. For this reason, along with the desire to secure the frisbee strongly and "cleanly", the general advice is to strongly prefer a two hands if possible.

The most popular throws are backhand, and forehand/flick and less frequently, hammer and scoober or any other throw. Part of the area of ultimate where skill and strategy meet is a player's capacity to plot and execute on throwing and passing to outrun another team, which is colloquially known as "being a deep threat". For example, multiple throwing techniques and the ability to pass the disc before the defense has had a chance to reset helps increase a player or team's threat level, and merging that with speed and coordinated plays can form a phalanx that is hard for competitors to overcome.

Apart from these formal strategies, there is also a freestyle practice, where players throw and catch with fewer limitations, in order to advance their ultimate handling skills.[40]

Strategy and tactics

Offense

Teams can employ many different offensive strategies, each with distinct goals. Most basic strategies are an attempt to create open space (e.g. lanes) on the field in which the thrower and receiver can complete a pass. Organized teams assign positions to the players based on their specific strengths. Designated throwers are called handlers and designated receivers are called cutters. The amount of autonomy or overlap between these positions depends on the make-up of the team.

Many advanced teams develop variations on the basic offenses to take advantage of the strengths of specific players. Frequently, these offenses are meant to isolate a few key players in one-on-one situations, allowing them more freedom of movement and the ability to make most of the plays, while the others play a supporting role.

Handlers and cutters

In most settings, there are a few "handlers" which are the players positioned around the disc, and their task is to distribute the disc forward, and provide easy receiving options to whoever has the disc. Cutters, are the players positioned downfield, whose job is usually to catch the disc farther afield and progress the disc through the field or score goals by catching the disc in the end zone.

Typically, when the offense is playing against a zone defense the cutters will be assigned positions based on their location on the field, often times referred to as "poppers and rails." Poppers will typically make cuts within 15 yards of the handler positions while rails alternate between longer movements downfield. Additionally, against a zone there will usually be three handlers rather than two, and sometimes even four.

Vertical stack

The standard configuration for a vertical stack (offense and force/one-to-one defense)

One of the most common offensive strategies is the vertical stack. In this strategy, a number of offensive players line up between the disc and the end zone they are attacking. From this position, players in the stack make cuts (sudden sprints, usually after throwing off the defender by a "fake" move the other way) into the space available, attempting to get open and receive the disc. The stack generally lines up in the middle of the field, thereby opening up two lanes along the sidelines for cuts, although a captain may occasionally call for the stack to line up closer to one sideline, leaving open just one larger cutting lane on the other side. Variations of the vertical stack include the Side Stack, where the stack is moved to a sideline and one player is isolated in the open space, and the Split Stack, where players are split between two stacks, one on either sideline. The Side Stack is most helpful in an end zone play where your players line up on one side of the end zone and the handler calls an "ISO" (isolation) using one of the player's names. This then signals for the rest of the players on your team to clear away from that one person in order for them to receive a pass.[41] In vertical stack offenses, one player usually plays the role of 'dump', offering a reset option which sets up behind the player with the disc.

Horizontal stack

Another popular offensive strategy is the horizontal stack. In the most popular form of this offense, three "handlers" line up across the width of the field with four "cutters" downfield, spaced evenly across the field. This formation encourages cutters to attack any of the space either towards or away from the disc, granting each cutter access to the full width of the field and thereby allowing a degree more creativity than is possible with a vertical stack. If cutters cannot get open, the handlers swing the disc side to side to reset the stall count and in an attempt to get the defense out of position. Usually players will cut towards the disc at an angle and away from the disc straight, creating a 'diamond' or 'peppermill' pattern.[42][43][44][45]

Feature, German, or isolation

A variation on the horizontal stack offense is called a feature, German, or isolation (or "iso" for short). In this offensive strategy three of the cutters line up deeper than usual (this can vary from 5 yards farther downfield to at the endzone) while the remaining cutter lines up closer to the handlers. This closest cutter is known as the "feature", or "German". The idea behind this strategy is that it opens up space for the feature to cut, and at the same time it allows handlers to focus all of their attention on only one cutter. This maximizes the ability for give-and-go strategies between the feature and the handlers. It is also an excellent strategy if one cutter is superior to other cutters, or if they are guarded by someone slower than them. While the main focus is on the handlers and the feature, the remaining three cutters can be used if the feature cannot get open, if there is an open deep look, or for a continuation throw from the feature itself. Typically, however, these three remaining cutters do all they can to get out of the feature's way.[46]

Hexagon or Mexican

A newer strategy, credited to Felix Shardlow from the Brighton Ultimate team, is called Hexagon Offence. Players spread out in equilateral triangles, creating a Hexagon shape with one player (usually not the thrower) in the middle. They create space for each other dynamically, aiming to keep the disc moving by taking the open pass in any direction. This maximizes options, changes the angles of attack rapidly, and hopes to create and exploit holes in the defense. Whereas vertical and horizontal aim to open up space for individual yard-gaining throws, Hex aims to generate and maintain flow to lead to scoring opportunities.[47]

Defense

The marker blocking the handler's access to half of the field. Tartu, Estonia.

Pull

The pull is the first throw of the game and also begins each period of play. A strong accurate pull is an important part of a defensive strategy. A pullers responsibility is to start the offense as deep into their own end-zone as conditions will permit, giving the defense time to get set up before the first offensive pass, or in the case of a deep end-zone pull, chooses to run up to the front of their end-zone line and begin their offense at yard zero.[48]

Force

One of the most basic defensive principles is the "force" or "mark". The defender marking the thrower essentially tries to force them to throw in a particular direction (to the "force side" or "open side"), whilst making it difficult for them to throw in the opposite direction (the "break side"). Downfield defenders make it hard for the receiving players to get free on the open/force side, knowing throws to the break side are less likely to be accurate. The space is divided in this way because it is very hard for the player marking the disc to stop every throw, and very hard for the downfield defenders to cover every space.

The force can be decided by the defence before the point or during play. The most common force is a one-way force, either towards the "home" side (where the team has their bags/kit), or "away". Other forces are "sideline" (force towards the closest sideline), "middle" (force towards the center of the field), "straight up" (the force stands directly in front of the thrower – useful against long throwers), or "sidearm/backhand" if one wishes their opponents to throw a particular throw. Another, more advanced marking technique is called the "triangle mark". This involves shuffling and drop stepping to take away throwing angles in an order that usually goes: 1) take away shown throw "inside" 2) shuffle to take away 1st pivot "around" 3) drop step and shuffle to take away 2nd pivot 4) recover.[49][50][51]

Man-to-man

Marking with a force

The simplest defensive strategy is the man-to-man defense (also known as "one-to-one" or "person-to-person"), where each defender guards a specific offensive player, called their "mark". This defense creates one-to-one matchups all over the field – if each defender shuts out their mark, the team will likely earn a turn over. The defensive players will usually choose their mark at the beginning of the point before the pull. Often players will mark the same person throughout the game, giving them an opportunity to pick up on their opponent's strengths and weaknesses as they play.[52]

Zonal

With a zonal defensive strategy, the defenders cover an area rather than a specific person. The area they cover varies depending on the particular zone they are playing, and the position of the disc. Zone defense is frequently used in poor weather conditions, as it can pressure the offense into completing more passes, or the thrower into making bigger or harder throws. Zone defence is also effective at neutralising the deep throw threat from the offense. A zone defense usually has two components – (1) a number of players who stay close to the disc and attempt to contain the offenses' ability to pass and move forward (a "cup" or "wall"), and (2) a number of players spaced out further from the disc, ready to bid on overhead or longer throws.[53][54][55]

Cup

An offensive player tries to play through a three-man cup defense during an informal game.

The cup involves three players, arranged in a semi-circular cup-shaped formation, one in the middle and back, the other two on the sides and forward. One of the side players marks the handler with a force, while the other two guard the open side. Therefore, the handler will normally have to throw into the cup, allowing the defenders to more easily make blocks. With a cup, usually the center cup blocks the up-field lane to cutters, while the side cup blocks the cross-field swing pass to other handlers. The center cup usually also has the responsibility to call out which of the two sides should mark the thrower, usually the defender closest to the sideline of the field. The idea of the cup is to force the offense into making many short passes behind and around the cup. The cup (except the marker) must also remember to stay 3 meters or more away from the offensive player with the disc. The only time a player in the cups can come within 3 meters of the player with the disc is when another offensive player comes within 3 meters of the person with the disc, also known as "crashing the cup".[53]

Wall

The "wall" sometimes referred to as the "1-3-3" involves four players in the close defense. One player is the marker, also called the "rabbit", "chaser" or "puke" because they often have to run quickly between multiple handlers spread out across the field. The other three defenders form a horizontal "wall" or line across the field in front of the handler to stop throws to short in-cuts and prevent forward progress. The players in the second group of a zone defense, called "mids" and "deeps", position themselves further out to stop throws that escape the cup and fly upfield. A variation of the 1-3-3 is to have two markers: The "rabbit" marks in the middle third and strike side third of the field. The goal is for the "rabbit" to trap the thrower and collapse a cup around him. If the rabbit is broken for large horizontal yardage, or if the disc reaches the break side third of the field, the break side defender of the front wall marks the throw. In this variation the force is directed one way. This variation plays to the strength of a superior marking "rabbit".[56][57]

Junk or clam

A junk defense is a defense using elements of both zone and man defenses; the most well-known is the "clam" or "chrome wall". In clam defenses, defenders cover cutting lanes rather than zones of the field or individual players. It is so named because, when played against a vertical stack, it is often disguised by lining up in a traditional person defense and right before play starts, defenders spread out to their zonal positions, forming the shape of an opening clam. The clam can be used by several players on a team while the rest are running a man defense. Typically, a few defenders play man on the throwers while the cutter defenders play as "flats", taking away in cuts by guarding their respective areas, or as the "deep" or "monster", taking away any deep throws.

This defensive strategy is often referred to as "bait and switch". In this case, when the two players the defenders are covering are standing close to each other in the stack, one defender will move over to shade them deep, and the other will move slightly more towards the thrower. When one of the receivers makes a deep cut, the first defender picks them up, and if one makes an in-cut, the second defender covers them. The defenders communicate and switch their marks if their respective charges change their cuts from in to deep, or vice versa. The clam can also be used by the entire team, with different defenders covering in cuts, deep cuts, break side cuts, and dump cuts.

The term "junk defense" is also often used to refer to zone defenses in general (or to zone defense applied by the defending team momentarily, before switching to a man defense), especially by members of the attacking team before they have determined which exact type of zone defense they are facing.[58][59][60]

Hexagon or flexagon

A separate type of defense is hexagon or "flexagon", which incorporates elements of both man-to-man and zonal defense. All defenders are encouraged to communicate, to sandwich their opponents and switch marks wherever appropriate, and to ensure no opposing player is left unmarked.[61]

Spirit of the game

A disputed foul was called by the Swedish player (in blue) after this attempted block in the 2007 European Championship final between Great Britain and Sweden in Southampton, UK.

All youth and most club ultimate games are self-officiated through the "spirit of the game", often abbreviated SOTG. Spirit of the game is described by WFDF as an expectation that each player will be a good sport and play fair, including "following and enforcing the rules".[62] SOTG is further contextualized and described in the rules established by USA Ultimate; according to The Official Rules of Ultimate, 11th Edition:[63]

Ultimate has traditionally relied upon a spirit of sportsmanship which places the responsibility for fair play on the player. Highly competitive play is encouraged, but never at the expense of the bond of mutual respect between players, adherence to the agreed upon rules of the game, or the basic joy of play. Protection of these vital elements serves to eliminate adverse conduct from the ultimate field. Such actions as taunting of opposing players, dangerous aggression, intentional fouling, or other 'win-at-all-costs' behavior are contrary to the spirit of the game and must be avoided by all players.

Many tournaments give awards for the most spirited teams and/or players, often based on ratings provided by opposing teams. The largest youth ultimate tournament in the world, Spring Reign, uses spirit scores to award a spirit prize within each pool and to determine eligibility of teams the following year.[64] In many non-professional games, it is common for teams to meet after the game in a "spirit circle" to discuss the game, and in some cases grant individual spirit awards.

While "spirit of the game" is a general attitude, ultimate has an agreed upon procedure to deal with unclear or disputed situations.[65]

In Europe and other continents, even top-level play does not have referees. Some world championship games have had no referees, and disputes were decided by the players themselves.

"Observers" are used in some high-level tournaments outside the US, as well as in some tournaments sanctioned by USA Ultimate. Calls and disputes are initially handled by the players, but observers step in if no agreement is reached. In some settings, officials use a stopwatch to track the stall count and the defending players are not counting the stall.

Other forms of refereeing exist in ultimate. Professional ultimate in North America uses referees, in part to increase the pace of the game. Game Advisors are used in some international competitions, though calls and final decisions remain in control of the on-field players.

Competitions

The common types of competitions are:

- Hat tournaments – random player allocations, mixed levels, and amateur

- Club leagues – usually considered semi-professional

- Pro ultimate – usually refers to the full league played by the American Ultimate Disc League during the regular season between April and August, with a championship week for the title

- College teams

- National teams competing in international tournaments

Professional league – AUDL

North America has the American Ultimate Disc League (AUDL), a professional-level ultimate league that involve teams from the United States and Canada.

The AUDL was founded by Josh Moore and its inaugural season began in April 2012. In 2013 the league was bought by Ultimate Xperience Ventures LLC, a company founded by Rob Lloyd who was serving as VP of Cisco but has since become the CEO of Hyperloop. In 2012 the league began with eight teams, but currently consists of 26 teams in four divisions (East, South, Midwest, and West). Since the league's inaugural season, they have added 24 new teams and had 10 teams fold. Only two of the original eight teams remain in the league (Detroit Mechanix and Indianapolis Alleycats). Each team plays a total of 14 regular season games on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday during the months of April through July. In late July there are playoffs in each division followed by a championship weekend held the first weekend in August. The AUDL uses the Discraft Ultrastar as the official game disc. The team funding comes from sources similar to those of other professional sports: sales of tickets, merchandise, concessions and sponsorship.[66] In 2014, the league entered an agreement with ESPN to broadcast 18 games per season for a 2-year period (with a 3rd year option) on the online streaming service ESPN3. That contract was executed by Fulcrum Media Group.

There used to be a rival league named Major League Ultimate (MLU). Active between 2013 and 2016, it had eight teams, and was considered the main alternative to the AUDL, until it closed down.

In 2018, there was a planned mixed league called the United Ultimate League (UUL),[67] but it failed due to a lack of interest. The plan was to present an alternative to the AUDL, which at the time was dealing with a boycott related to gender equality. The UUL was supposed to be supported by crowd sourced funding, but the initial Kickstarter failed, raising only $23,517 of the $50,000 goal.

North American leagues

Regulation play, sanctioned in the United States by the USA Ultimate, occurs at the college (open and women's divisions), club (open, women's, mixed [male + female on each team], masters, and grandmasters divisions) and youth levels (in boys and girls divisions), with annual championships in all divisions. Top teams from the championship series compete in semi-annual world championships regulated by the WFDF (alternating between Club Championships and National Championships), made up of national flying disc organizations and federations from about 50 countries.

Australia vs. Canada ultimate players at WUGC 2012 in Japan. Ultimate Canada

Ultimate Canada (UC) is the governing body for the sport of ultimate in Canada.[28] Beginning in 1993, the goals of UC include representing the interests of the sport and all ultimate players, as well as promoting its growth and development throughout Canada. UC also facilitates open and continuous communication within the ultimate community and within the sports community and to organize ongoing activities for the sport including national competitions and educational programs.[17]

Founded in 1986, incorporated in 1993, the Ottawa-Carleton Ultimate Association based in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, claims to have the largest summer league in the world with 354 teams and over 5000 players as of 2004.[68]

The Vancouver Ultimate League, based in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, formed in 1986, claims to have 5300 active members as of 2017.[69]

The Toronto Ultimate Club,[70] founded in 1979 by Ken Westerfield and Chris Lowcock, based in Toronto Canada, has 3300 members and 250 teams, playing the year round.[71][17]

The Los Angeles Organization of Ultimate Teams puts on annual tournaments with thousands of players.

There have been a small number of children's leagues. The largest and first known pre-high school league was started in 1993 by Mary Lowry, Joe Bisignano, and Jeff Jorgenson in Seattle, Washington.[72] In 2005, the DiscNW Middle School Spring League had over 450 players on 30 mixed teams. Large high school leagues are also becoming common. The largest one is the DiscNW High School Spring League. It has both mixed and single gender divisions with over 30 teams total. The largest adult league is the San Francisco Ultimate League, with 350 teams and over 4000 active members in 2005, located in San Francisco, California. The largest per capita is the Madison Ultimate Frisbee association, with an estimated 1.8% of the population of Madison, WI playing in active leagues. Dating back to 1977, the Mercer County (New Jersey) Ultimate Disc League (www.mercerultimate.org) is the world's oldest recreational league. There are even large leagues with children as young as third grade, an example being the junior division of the SULA ultimate league in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Other countries have their own regional and country wide competitions, which are not listed here.

College teams

There are over 12,000 student athletes playing on over 700 college ultimate teams in North America,[73] and the number of teams is steadily growing.

Ultimate Canada operates one main competition for university ultimate teams in Canada: Canadian University Ultimate Championships (CUUC) with six qualifying regional events, one of which is the Canadian Eastern University Ultimate Championships (CEUUC).[28]

National teams

There are also national teams participating in international tournament, both field and beach formats.

Yearly or twice-yearly national competitions are held. [4]

In the USA and other countries, the national teams is selected after an arduous tryout process.[74]

WFDF maintains an international ranking list for the national teams [75]

Hat tournaments

Hat tournaments are common in the ultimate circuit. At these tournaments players join individually rather than as a team. The tournament organizers form teams by randomly taking the names of the participants from a hat. This sort of procedure is an excellent way to meet people from all skill levels.

Many hat tournaments on the US west coast have a "hat rule" requiring all players to wear a hat at all times during play. If a player gains possession of the disc, yet loses his hat in the process, the play is considered a turnover and possession of the disc reverts to the other team.[76]

However, in some tournaments, the organizers do not actually use a hat, but form teams while taking into account skill, experience, sex, age, height, and fitness level of the players in the attempt to form teams of even strength. Many times the random element remains, so that organizers randomly pick players from each level for each team, combining a lottery with skill matching. Usually, the player provides this information when he or she signs up to enter the tournament. There are also many cities that run hat leagues, structured like a hat tournament, but where the group of players stay together over the course of a season.

Common concepts and terms

- layout

- A player extends his body horizontally towards the disc, ending up lying on the ground usually. This can happen offensively to catch a far or low disc, or defensively to hit the disc and force a turnover.[77]

- Callahan

- A defensive player catches the disc in the far end endzone while defending. This yields an immediate score for the defending team (akin to an own goal in other sports), as this endzone is their endzone to score in.[78]

- D

- Getting the defense or turnover.

- greatest

- A player jumps to out of bounds for the disc, and while in the air throws back the disc to be caught inside the field of play.[79]

- sky

- To grab the disc in the air over the opponent.

- huck

- To throw the disc a long distance.

- spike

- To throw the disc to the ground forcefully after scoring; borrowed from American football.

- brick

- when the pull goes out of bound, the game starts at the brick point somewhat infront of the center of the endzone. (The offensive player picking up the disc signals that he wants to play from there clapping hands above head)

Other terms are borrowed from football with similar meanings, including goal, assist, and pass completion.

Rundquist

To throw the disc immediately out of bounds on the pull giving the other team field position at their goal line

Bookends

To both cause the turnover and score the point

See also

Player trying to score.

Competitions and Leagues:

- American Ultimate Disc League

- Major League Ultimate

- USA Ultimate

- World Flying Disc Federation

- List of Ultimate teams

- U.S. intercollegiate Ultimate champions

- Ultimate Canada

- Ultimate in Japan

- Beach Ultimate Lovers Association

- Deutscher Frisbeesport-Verband

Disc games and other:

- Disc golf

- Disc throws

- Flying disc

- Flying disc freestyle

- Flying disc games

- Goaltimate

Misc:

- Ken Westerfield

- Ultimate glossary

Currier Island, a fictional nation competing in national beach ultimate events

- History of Early Frisbee Sport

- History of Ultimate and Disc Golf

References

^ "IOC Session receives updates on implementation of Olympic Agenda 2020". Olympic News. August 2, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "World Flying Disc Federation Receives Recognition by the International Olympic Committee". World Flying Disc Federation. May 31, 2013.

^ ab Bethea, Charles (August 12, 2015). "Ultimate Frisbee's Surprising Arrival as a Likely Olympic Sport". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

^ "What Is Ultimate?". USAUltimate.org. USA Ultimate. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

^ ab "About Spirit of the Game". USAUltimate.org. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee Participation [SFIA]". Sludge Output. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

^ "2014 World Ultimate Club Championships (WUCC)". www.wfdf.org. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

^ "Pools & Standings". #WCBU2017 live. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

^ "Final Standings". #WCBU2017 live. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

^ abc Leonardo, Pasquale Anthony; Zagoria, Adam (2005). Seidler, Joe, ed. Ultimate: The First Four Decades. Ultimate History Inc. ASIN B01A0CKFHK. ISBN 0976449609. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

^ "Ultimate History – General". Retrieved January 23, 2015 – via Vimeo.com.

^ abcdefgh Iacovella, Michael E. "An Abbreviated History of Ultimate". wfdf.org. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

^ "Major Steps in History of Ultimate". WFDF.org. World Flying Disc Federation. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

^ "Timeline of early history of Flying Disc Play (1871–1995)". WFDF.org. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

^ "History of the Frisbee". WFDF.org. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

^ "History of Frisbee and Flying Disc freestyle". Development of Frisbee in the US and Canada. Retrieved February 6, 2018. Note: The Canadian Open Frisbee Championships (1972) in Toronto Canada and the Vancouver Open Frisbee Championships (1974) along with the IFT Guts Frisbee tournament in Northern Michigan were the first tournaments to introduce Frisbee as a disc sport (up until then, the Frisbee was only used as a toy.

^ abc "History of Frisbee and Flying Disc freestyle". Development of Frisbee in Canada. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

^ "TUC History". Toronto Ultimate Club History. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

^ ab "Special Merit: The "80 Mold"". USAUltimate.org. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

^ "FPA Freestyle Disc Hall of Fame Pioneer Class Inductee Jim Kenner". Retrieved April 10, 2016.

^ "Ultimate Hall of Fame". USAUltimate.org. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

^ "The Discraft Ultrastar (Class of 2011)". USAUltimate.org. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

^ "When Wham-O Was King: Why The Innova V. Discraft Debate Is Old News". UltiWorld.com. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

^ Holtzman-Conston, Jordan (2010). Countercultural Sports in America: The History and Meaning of Ultimate Frisbee. Waltham, Mass: Lambert Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-3838311951.

^ abc Ring, Wilson (2017-11-06). "Vermont first state to recognize 'ultimate' as varsity sport". Associated Press. Daily Hampshire Gazette. Archived from the original on 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

^ Mills, Stephen (2018-02-12). "Watson to run unchallenged for Capital City mayor". Barre Montpelier Times Argus. Archived from the original on 2018-05-06. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

^ ab Eisenhood, Charlie (2017-11-03). "Vermont Becomes First State To Approve Ultimate As High School Varsity Sport". Ultiworld. Archived from the original on 2017-11-10. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

^ abc "[Home page]". CanadianUltimate.com. Ultimate Canada. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

^ "'Ultimate Frisbee' recognised by International Olympic Committee". BBC News.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee recognized by International Olympic Committee". Sports Illustrated. Time Inc.

^ ab "Rules of Ultimate". USAUltimate.org. USA Ultimate. August 1, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

^ "9. Stall count" (PDF). Wfdf.org. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

^ "11th Edition Rules". www.usaultimate.org. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

^ "20. Time-Outs". WFDF Rules of Ultimate. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

^ "Ultimate". February 12, 2012. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

^ "Ultimate". Wfdf.org. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

^ Bernardi, Volker. "WFDF approves transgender athlete policy". www.wfdf.org. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

^ "Downloads | Ultimate | Rules of Play". Wfdf.org. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Rules - The AUDL". Theaudl.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

^ "Freestyle the Ultimate Edge". Retrieved November 13, 2015.

^ "Ultimate Terms and Lingo". Ultimate Frisbee HQ. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Nadeau, Ben (August 1, 2016). "CoachUp Nation | Excelling In The Horizontal Stack". Coachup.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Horizontal Offense | Vancouver Ultimate League". Vul.ca. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Considering The Horizontal Stack: Are You Sure It's Right For Your Team?". Ultiworld.com. August 27, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Handbook". UltimateHandbook.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee | American Football – The 4-1-2 'German' offense". Playspedia.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Hexagon Offence –". Felixultimate.com. April 14, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ Westerfield, Ken. "The Art and Psychology of the Ultimate Pull". Ultimate Rob. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

^ Rob, Ultimate. "Forcing in Ultimate – What Does it Mean?". Ultimate Rob. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Basics". UltimateHandbook.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Mailbag with Mario: Playing Time, Defense, and Triangle Marking". Ultiworld.com.

^ Hordern, Tim (March 15, 2013). "Ultimate Frisbee Defensive Skills". TimHordern.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ ab "The Cup: Defensive zone plays". Ultimate Frisbee HQ. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Handbook". UltimateHandbook.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Zone Defenses At College Nationals: A Reference Guide to Playing (and Beating) Junks". UltiWorld. May 19, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee | American Football – The Wall". Playspedia.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee | American Football – 1-3-3 Zone Defense". Playspedia.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Junk defense - Ultipedia". March 7, 2007. Archived from the original on March 7, 2007. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee | American Football – Clam (5/50)". Playspedia.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Frisbee | American Football – Clam Zone Defense". Playspedia.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Flexagon Defence –". FelixUltimate.com. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Spirit of the game". WFDF.org. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

^ "11th Edition Rules". USAUltimate.org. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

^ "Spring Reign (2015)". DiscNW. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

^ "Basic Rules". WFDF.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

^ Earley, Mark. "Ultimate Interviews". UltimateInterviews.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

^ [1]

^ "Play Ultimate". OCUA.ca. Ottawa Carleton Ultimate Association. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

^ "About the Vancouver Ultimate League Society". VUL.ca. Vancouver Ultimate League. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "[Home page]". TUC.org. Toronto Ultimate Club. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

^ "TUC History". Toronto Ultimate Club History. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

^ Bock, Paula (July 24, 2005). "The Sport of Free Spirits". The Seattle Times Sunday Magazine. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

^ "College Division". USAUltimate.org. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "News USA Ultimate Announces New Team Selection Procedures For WUGC". USAUltimate.org. December 8, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "World Rankings". Wfdf.org. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "Ultimate Field Locator – Ultimate Frisbee Pickup Games & Tournaments: Hat Tournament Rules". Ultimatefieldlocator.info. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "All Ultimate Frisbee Terms and lingo – L". The Ultimate HQ. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "All Ultimate Frisbee Terms and lingo – C". The Ultimate HQ. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

^ "All Ultimate Frisbee Terms and lingo – G". The Ultimate HQ. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ultimate frisbee. |

- World Flying Disc Federation official website

- American Ultimate Disc League website