Colorectal polyp

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| Colon polyps | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polyp of sigmoid colon as revealed by colonoscopy. Approximately 1 cm in diameter. The polyp was removed by snare cautery. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

A colorectal polyp is a polyp (fleshy growth) occurring on the lining of the colon or rectum.[1] Untreated colorectal polyps can develop into colorectal cancer.[2]

Colorectal polyps are often classified by their behaviour (i.e. benign vs. malignant) or cause (e.g. as a consequence of inflammatory bowel disease).

They may be benign (e.g. hyperplastic polyp), pre-malignant (e.g. tubular adenoma) or malignant (e.g. colorectal adenocarcinoma).

Contents

1 Signs and symptoms

2 Structure

3 Types

3.1 Hyperplastic polyp

3.2 Neoplastic polyp

3.2.1 Adenomas

3.3 Hamartomatous polyp

3.4 Inflammatory polyp

4 Diagnosis

5 Prevention

6 Treatment

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Signs and symptoms

Colorectal polyps are not usually associated with symptoms.[2] When they occur, symptoms include rectal bleeding, bloody stools, abdominal pain and fatigue.[2] Due to chronic blood loss from rectal bleeding and bloody stools, they sometimes present with iron deficiency anemia.[3] Other symptom might be increased mucous production especially those involving villous adenomas[3]. Copious production of mucous causes loss of potassium that can occasionally result in symptomatic hypokalemia[3]. A change in bowel habits may occur including constipation and diarrhoea.[4] Occasionally, if a polyp is big enough to cause a bowel obstruction, there may be nausea, vomiting and severe constipation.[4]

Structure

Polyps are either pedunculated (attached to the intestinal wall by a stalk) or sessile (grow directly from the wall).[5] In addition to the gross appearance categorization, They are further divided by their histologic appearance as tubular adenoma which are tubular glands, villous adenoma which are long finger like projections on the surface, and tubulovillous adenoma which has features of both[6].

Types

The most common general classification is:

- hyperplastic,

- neoplastic (adenomatous & malignant),

- hamartomatous and,

- inflammatory.

Hyperplastic polyp

Most hyperplastic polyps are found in the distal colon and rectum.[7] They have no malignant potential,[7] which means that they are no more likely than normal tissue to eventually become a cancer.

Hyperplastic polyps are serrated polyps. Hyperplastic polyps have three histologic patterns of growth: microvesicular, goblet cell and mucin poor.

Hyperplastic polyposis syndrome is a rare condition that has been defined by the World Health Organization as either:

- Five or more hyperplastic polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon, with two polyps greater than 10mm in diameter; or

- Any number of hyperplastic polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in a person with a first degree relative who has hyperplastic polyposis syndrome; or

- More than 30 hyperplastic polyps of any size throughout the colon and rectum.[8]

Although thought to exhibit no malignant potential, hyperplastic polyps have been shown that on the right side of the colon do exhibit a malignant potential. This occurs through multiple mutations which affect the DNA-mismatch-repair pathways. As such DNA mutations during replication are not repaired. This leads to microsatellite instability which can eventually lead to malignant transformation in polyps on the right side of the colon.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP)

FAP is a form of hereditary cancer syndrome involving the APC gene located on chromosome q521.[6] The syndrome was first described in 1863 by Virchow on a 15-year-old boy with multiple polyps in his colon.[6] The syndrome involves development of multiple polyps at an early age and those left untreated will all eventually develop cancer.[6] The gene is expressed 100% in those with the mutation and it is autosomal dominant.[6] 10% to 20% of patients have negative family history and acquire the syndrome from spontaneous germline mutation.[6] The average age of newly diagnosed patient is 29 and the average age of newly discovered colorectal cancer is 39.[6] It is recommended that those affected undergo colorectal cancer screening at younger age with treatment and prevention are surgical with removal of affected tissues.[6]

Lynch Syndrome

Also unknown as hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer or HNPCC is an hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome.[6] It is the most common hereditary form of colorectal cancer in the United States and accounts for about 3% of all cases of cancer.[6] It was first recognized by Alder S. Warthin in 1885 at the University of Michigan.[6] It was later further studied by Henry Lynch who recognized an autosomal dominant transmission pattern with those affected having relatively early onset of cancer (mean age 44 years), greater occurrence of proximal lesions, mostly mucinous or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, greater number of synchronous and metachronous cancer cells, and good outcome after surgical intervention.[6] The Amsterdam Criteria was initially used to define Lynch syndrome before the underlying genetic mechanism had been worked out.[6] The Criteria required that the patient has 3 family members all first-degreee relatives with colorectal cancer that involves at least 2 generations with at least 1 affected person being younger than 50 years of age when the diagnosis was made.[6] The Amsterdam criteria is too restrictive and was later expanded to include cancers of endometrial, ovarian, gastric, pancreatic, small intestinal, ureteral, and renal pelvic origin.[6] The increased risk of cancer seen in patients with by the syndrome is associated with dysfunction of DNA repair mechanism.[6] Molecular biologists have linked the syndrome to specific genes such as hMSH2, hMSH1, hMSH6, and hPMS2.[6]

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

An autosomal dominant syndrome that presents with hamartomatous polyps, which are disorganized growth of tissues of the intestinal tract, and hyperpigmentation of the interlining of the mouth, lips and fingers.[6] The syndrome was first noted in 1896 by Hutchinson, and later separately described by Peutz, and then again in 1940 by Jeghers.[6] The syndrome is associated with malfunction of serine-threonine kinase 11 or STK 11 gene, and has a 2% to 10% increase in risk of developing cancer of the intestinal tract.[6] The syndrome also causes increased risk of extraintestinal cancer such as that involving breast, ovary, cervix, fallopian tubes, thyroid, lung, gallbladder, bile ducts, pancreas, and testicles.[6] The polyps often bleeds and may cause obstruction that would require surgery.[6] Any polyps larger than 1.5 cm needs removal and patients should be monitored closely and screen every 2 years for malignancy.[6]

Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome

It is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by increased risk of cancer of intestinal tract and extraintestinal cancer.[6] It often presents with bleeding and obstruction of the intestinal tract along with low serum albumin due to protein loss in the intestine.[6] The syndrome is linked to malfunction of SMAD4 a tumor suppression gene which is seen in 50% of cases.[6] Individuals with multiple juvenile polyps have at least 10% chance of developing malignancy and should undergo abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, and close monitoring via endoscopy of rectum.[6] For individuals with few juvenile polyps, patients should undergo endoscopic polypectomy.[6]

Neoplastic polyp

A neoplasm is a tissue whose cells have lost its normal differentiation. They can be either benign growths or malignant growths. The malignant growths can either have primary or secondary causes. Adenomatous polyps are considered precursors to cancer and cancer becomes invasive once malignant cells cross the muscularis mucosa invades the cells below.[6] Any cellular changes seen above the lamina propria are considered none invasive and are labeled atypia or dysplasia. Any invasive carcinoma that has penetrated the muscularis mocos has the potential for lymph node metastasis and local recurrence which will require more aggressive and extensive resection.[6] The Haggitt's criteria is used for classification of polyps containing cancer and is based on the depth of penetration.[6] The Haggitt's criteria has level 0 through level 4 with all invasive carcinoma of sessile polyp variant by definition be classified as level 4.[6]

Level 0: Cancer does not penetrate through the muscularis mucosa.[6]

Level 1: Cancer penetrates through the muscularis mucosa and invades the submucosa below but is limited to the head of the polyp.[6]

Level 2: Cancer invades through with involvement of the neck of polyp.[6]

Level 3: Cancer invades through with involvement of any parts of the stalk.[6]

Level 4: Cancer invades through the submucosa below the stalk of the polyp but above the muscularis propria of the bowel wall.[6]

Adenomas

Neoplastic polyps of the bowel are often benign hence called adenomas. An adenoma is a tumor of glandular tissue, that has not (yet) gained the properties of a cancer.

The common adenomas of the colon (colorectal adenoma) are the tubular, tubulovillous, villous, and sessile serrated (SSA).[7] A vast majority about 65% to 80% are of the benign tubular type with 10% to 25% being tubulovillous, and villous being the most rare at 5% to 10%.[6]

As is evident from their name, sessile serrated and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) have a serrated appearance and can be difficult to distinguish microscopically from hyperplastic polyps.[7] Making this distinction is important, however, since SSAs and TSAs have the potential to become cancers,[8] while hyperplastic polyps do not.[7]

The villous subdivision are associated with the highest malignant potential because they generally have the largest surface area. (This is because the villi are projections into the lumen and hence have a bigger surface area.) However, villous adenomas are no more likely than tubular or tubulovillous adenomas to become cancerous if their sizes are all the same.[7]

Hamartomatous polyp

Hamartomatous polyps are tumours, like growths found in organs as a result of faulty development. They are normally made up of a mixture of tissues. They contain mucus-filled glands, with retention cysts, abundant connective tissue, and a chronic cellular infiltration of eosinophils.[9] They grow at the normal rate of the host tissue and rarely cause problems such as compression. A common example of a hamartomatous lesion is a strawberry naevus. Hamartomatous polyps are often found by chance; occurring in syndromes such as Peutz-Jegher Syndrome or Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is associated with polyps of the GI tract and also increased pigmentation around the lips, genitalia, buccal mucosa feet and hands. People are often diagnosed with Peutz-Jegher after presenting at around the age of 9 with an intussusception. The polyps themselves carry little malignant potential but because of potential coexisting adenomas there is a 15% chance of colonic malignancy.

Juvenile polyps are hamartomatous polyps which often become evident before twenty years of age, but can also be seen in adults. They are usually solitary polyps found in the rectum which most commonly present with rectal bleeding. Juvenile polyposis syndrome is characterised by the presence of more than five polyps in the colon or rectum, or numerous juvenile polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract, or any number of juvenile polyps in any person with a family history of juvenile polyposis. People with juvenile polyposis have an increased risk of colon cancer.[8]

Inflammatory polyp

These are polyps which are associated with inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.

Diagnosis

Colorectal polyps can be detected using a faecal occult blood test, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, virtual colonoscopy, digital rectal examination, barium enema or a pill camera.[4]

Malignant potential is associated with

- degree of dysplasia

- Type of polyp (e.g. villous adenoma):

- Tubular Adenoma: 5% risk of cancer

- Tubulovillous adenoma: 20% risk of cancer

- Villous adenoma: 40% risk of cancer

- Size of polyp:

- <1 cm =<1% risk of cancer[10]

- 1-2 cm=10% risk of cancer[10]

- >2 cm=50% risk of cancer[10]

Normally an adenoma which is greater than 0.5 cm is treated

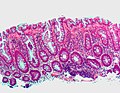

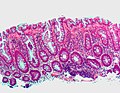

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp. H&E stain.

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp. H&E stain.

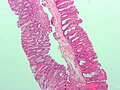

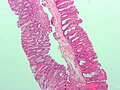

Traditional serrated adenoma. H&E stain.

Gross appearance of a colectomy specimen containing two colorectal polyps and one invasive colorectal carcinoma

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma, the most common type of dysplastic polyp in the colon.

Micrograph of a sessile serrated adenoma. H&E stain.

Micrograph of a Peutz-Jeghers colonic polyp - a type of hamartomatous polyp. H&E stain.

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma – dysplastic epithelium (dark purple) on left of image; normal epithelium (blue) on right. H&E stain.

Micrograph of a villous adenoma. These polyps are considered to have a high risk of malignant transformation. H&E stain.

Prevention

Diet and lifestyle are believed to play a large role in whether colorectal polyps form. Studies show there to be a protective link between consumption of cooked green vegetables, brown rice, legumes, and dried fruit and decreased incidence of colorectal polyps.[11]

Treatment

Polyps can be removed during a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy using a wire loop that cuts the stalk of the polyp and cauterises it to prevent bleeding.[4] Many "defiant" polyps—large, flat, and otherwise laterally spreading adenomas—may be removed endoscopically by a technique called endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), which involves injection of fluid underneath the lesion to lift it and thus facilitate surgical excision. These techniques may be employed as an alternative to the more invasive colectomy.[12]

See also

- Polyp table

References

^ Santero, Michael; Dennis Lee (2005-03-25). "Colon polyp symptoms, diagnosis and treatment". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2007-10-25..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abc Lehrer, Jenifer K. (2006-07-25). "Colorectal polyps". MedlinePlus. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

^ abc Clive R.G. Quick MB, BS(London), FDS, FRCS(England), MS(London), MA(Cambridge), Joanna B. Reed BMedSci(Hons), BM BS(Nottingham), FRCS(Eng), Simon J.F. Harper MB, ChB, BSc, FRCS, MD, Kourosh Saeb-Parsy MA, MB, BChir, FRCS, PhD and Philip J. Deakin BSc(Hons), MBChB(Sheffield) (2014). Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis and Management. Elsevier Ltd.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ abcd "Colon polyps". Mayo Clinic. 2007-07-16. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

^ Classen, Meinhard; Tytgat, G. N. J.; Lightdale, Charles J. (2002). Gastroenterological Endoscopy. Thieme. p. 303. ISBN 1-58890-013-4.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakal Najjia N. Mahmoud, Joshua I.S. Bleier, Cary B. Aarons, E. Carter Paulson, Skandan Shanmugan and Robert D. Fry (2017). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Elsevier, Inc.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ abcdef Kumar, Vinay (2010). "17 - Polyps". Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

^ abc Stoler, Mark A.; Mills, Stacey E.; Carter, Darryl; Joel K Greenson; Reuter, Victor E. (2009). Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7942-1.

[page needed]

^ Calva, Daniel; Howe, James R (2008). "Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes". Surgical Clinics of North America. 88 (4): 779–817, vii. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2008.05.002. PMC 2659506. PMID 18672141.

^ abc Summers, Ronald M (2010). "Polyp Size Measurement at CT Colonography: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know?". Radiology. 255 (3): 707–20. doi:10.1148/radiol.10090877. PMC 2875919. PMID 20501711.

^ Tantamango, Yessenia M; Knutsen, Synnove F; Beeson, W. Lawrence; Fraser, Gary; Sabate, Joan (2011). "Foods and Food Groups Associated with the Incidence of Colorectal Polyps: The Adventist Health Study". Nutrition and Cancer. 63 (4): 565–72. doi:10.1080/01635581.2011.551988. PMC 3427008. PMID 21547850.

^ "How I Do It" — Removing large or sessile colonic polyps. Archived 2008-04-11 at the Wayback Machine Brian Saunders; St. Mark’s Academic Institute; Harrow, Middlesex, UK. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

External links

| Classification | D

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

Villous Adenoma - Medscape