Ben Affleck

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Ben Affleck | |

|---|---|

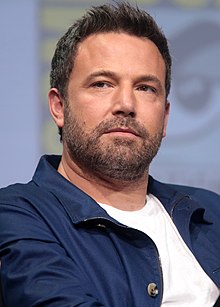

Affleck in 2017 | |

| Born | Benjamin Géza Affleck-Boldt (1972-08-15) August 15, 1972 Berkeley, California, U.S. |

| Residence | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Occidental College |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1981–present |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Jennifer Garner (m. 2005; div. 2018) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Casey Affleck (brother) |

Benjamin Géza Affleck-Boldt (born August 15, 1972) is an American actor and filmmaker. His accolades include two Academy Awards, three Golden Globe Awards, two BAFTA Awards, and two Screen Actors Guild Awards. He began his career as a child and starred in the PBS educational series The Voyage of the Mimi in 1984, before a second run in 1988. He later appeared in the independent coming-of-age comedy Dazed and Confused (1993) and various Kevin Smith films, including Chasing Amy (1997) and Dogma (1999). Affleck gained wider recognition when he and childhood friend Matt Damon won the Golden Globe and Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for writing Good Will Hunting (1997), which they also starred in. He then established himself as a leading man in studio films, including the disaster drama Armageddon (1998), the romantic comedy Forces of Nature (1999), the war drama Pearl Harbor (2001), and the spy thriller The Sum of All Fears (2002).

After a career downturn, during which he appeared in Daredevil and Gigli (both 2003), Affleck received a Golden Globe nomination for his performance in the noir biopic Hollywoodland (2006). His directorial debut, Gone Baby Gone (2007), which he also co-wrote, was well received. He then directed, co-wrote, and starred in the crime drama The Town (2010). For the political thriller Argo (2012), which he directed, co-produced, and starred in, Affleck won the Golden Globe and BAFTA Award for Best Director, and the Golden Globe, BAFTA, and Academy Award for Best Picture. He starred in the psychological thriller Gone Girl in 2014. In 2016, Affleck began playing Batman in the DC Extended Universe, starred in the action thriller The Accountant, and directed, wrote and acted in the gangster drama Live by Night.

Affleck is the co-founder of the Eastern Congo Initiative, a grantmaking and advocacy-based nonprofit organization. He is also a stalwart member of the Democratic Party. Affleck and Damon are co-owners of the production company Pearl Street Films. His younger brother is actor Casey Affleck, with whom he has worked on several films, including Good Will Hunting and Gone Baby Gone. Affleck married actress Jennifer Garner in 2005; they have three children together. The couple separated in 2015 and filed for divorce in early 2017.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Career

2.1 1981–1997: Child acting and Good Will Hunting

2.2 1998–2002: Leading man status

2.3 2003–2005: Career downturn and tabloid notoriety

2.4 2006–2015: Emergence as a director

2.5 2016–present: Batman role and continued directing

3 Humanitarian work

3.1 Eastern Congo Initiative

3.2 Other charitable causes

4 Politics

4.1 Political views

4.2 Democratic Party activism

5 Personal life

5.1 Relationships and family

5.2 Alcoholism

5.3 Professional gambling

5.4 Religion

5.5 Ancestry

5.6 TRL incident

6 Filmography and awards

7 References

8 External links

Early life

Benjamin Géza Affleck-Boldt was born on August 15, 1972, in Berkeley, California.[1][2][3] His family moved to Massachusetts when he was three,[4] living in Falmouth, where his brother Casey was born, before settling in Cambridge.[5] His mother, Christopher Anne "Chris" (née Boldt),[6] was a Harvard-educated elementary school teacher.[7][8] His father, Timothy Byers "Tim" Affleck,[9] was an aspiring playwright[9] who made a living as a carpenter,[10] auto mechanic,[4]bookie,[11] electrician,[12] bartender,[13] and janitor at Harvard.[14] In the mid-1960s, he had been an actor and stage manager with the Theater Company of Boston.[15] During Affleck's childhood, his father had a self-described "severe, chronic problem with alcoholism",[16] and Affleck has recalled him drinking "all day ... every day".[17] He and his younger brother attended Al-Anon support meetings from a young age.[18] His parents divorced when he was 12,[16] and he and Casey lived with their mother.[9] His father continued to drink,[7] and spent two years homeless.[11][19] When Affleck was 16, his father moved to Indio, California, to enter a rehabilitation facility and, after gaining sobriety, he lived at the facility for many years while working as an addiction counselor.[7][20]

Affleck was raised in a politically active, liberal household.[11][21] He and his brother were surrounded by people who worked in the arts,[22] regularly attended theater performances with their mother,[23] and were encouraged to make their own home movies.[24] The brothers auditioned for roles in local commercials and film productions because of their mother's friendship with a Cambridge-area casting director,[13] and Affleck first acted professionally at the age of seven.[25] His mother saved his wages in a college trust fund,[9] and hoped her son would ultimately become a teacher, worrying that acting was an insecure and "frivolous" profession.[26]David Wheeler, a family friend, was Affleck's acting coach and later described him as a "very bright and intensely curious" child.[25] When Affleck was 13, he filmed a children's television program in Mexico and learned to speak Spanish during a year spent traveling around the country with his mother and brother.[27]

As a Cambridge Rindge and Latin high school student, Affleck acted in theater productions and was inspired by drama teacher Gerry Speca.[28][29] During this time he became close friends with Matt Damon, whom he had known since the age of eight.[30] Although Damon was two years older, the two had "identical interests",[30] and traveled to New York together for acting auditions.[31] They saved their acting earnings in a joint bank account to buy train and airline tickets.[32] While Affleck had high SAT scores,[9] he was an unfocused student with poor attendance.[7][33] He spent a few months studying Spanish at the University of Vermont, chosen because of its proximity to his then-girlfriend,[12] but left after fracturing his hip while playing basketball.[31] At 18, Affleck moved to Los Angeles,[26] studying Middle Eastern affairs at Occidental College for a year and a half.[34][35]

Career

1981–1997: Child acting and Good Will Hunting

Affleck acted professionally throughout his childhood but, in his own words, "not in the sense that I had a mom that wanted to take me to Hollywood or a family that wanted to make money from me ... I kind of chanced into something."[36] He first appeared, at the age of seven, in a local independent film called Dark Side of the Street (1981), directed by a family friend.[37] His biggest success as a child actor was as the star of the PBS children's series The Voyage of the Mimi (1984) and The Second Voyage of the Mimi (1988), produced for sixth-grade science classes. Affleck worked "sporadically" on Mimi from the age of eight to fifteen in both Massachusetts and Mexico.[36] As a teenager, he appeared in the ABC after school special Wanted: A Perfect Man (1986),[38] the television film Hands of a Stranger (1987),[36] and a 1989 Burger King commercial.[29]

After high school, Affleck moved briefly to New York in search of acting work.[36] Later, while studying at Occidental College in Los Angeles, Affleck directed student films.[11][39] As an actor, he had a series of "knock-around parts, one to the next".[36] He played Patrick Duffy's son in the television film Daddy (1991), made an uncredited appearance as a basketball player in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer film (1992), and had a supporting role as a prep school student in School Ties (1992).[40] He played a high school quarterback in the NBC television series Against the Grain (1993), and a steroid-abusing high school football player in Body to Die For: The Aaron Henry Story (1994). Affleck's most notable role during this period was as a high school bully in Richard Linklater's cult classic Dazed and Confused (1993).[41] Linklater wanted a likeable actor for the villainous role and, while Affleck was "big and imposing," he was "so smart and full of life ... I just liked him."[42][43] Affleck later said Linklater was instrumental in demystifying the filmmaking process for him.[11]

Affleck and Matt Damon attend a Camp David screening of Good Will Hunting with President Bill Clinton in early 1998.

Affleck's first starring film role was as an aimless art student in the college drama Glory Daze (1995), with Stephen Holden of The New York Times remarking that his "affably mopey performance finds just the right balance between obnoxious and sad sack".[44] He then played a bully in filmmaker Kevin Smith's comedy Mallrats (1995), and became friends with Smith during the filming. Affleck began to worry that he would be relegated to a career of "throwing people into their lockers",[36] but Smith put him in the lead role in Smith's romantic comedy Chasing Amy (1997).[4][36] The film was Affleck's breakthrough.[36]Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised Affleck's "wonderful ease" playing the role, combining "suave good looks with cool comic timing".[45] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly described it as a "wholesome and quick-witted" performance.[46] When Affleck starred as a recently returned Korean War veteran in the coming-of-age drama Going All the Way (1997), Todd McCarthy of Variety found him "excellent",[47] while Janet Maslin of The New York Times noted that his "flair for comic self-doubt made a strong impression."[48]

The success of 1997's Good Will Hunting, which Affleck co-wrote and acted in, marked a turning point in his career. The screenplay originated in 1992 when Damon wrote a 40-page script for a playwriting class at Harvard University.[49] He asked Affleck to act out the scenes with him in front of the class and, when Damon later moved into Affleck's Los Angeles apartment, they began working on the script in earnest.[30] The film, which they wrote mainly during improvisation sessions, was set partly in their hometown of Cambridge, and drew from their own experiences.[49][50] They sold the screenplay to Castle Rock in 1994 when Affleck was 22 years old. During the development process, they received notes from industry figures including Rob Reiner and William Goldman.[51] Following a lengthy dispute with Castle Rock about a suitable director, Affleck and Damon persuaded Miramax to purchase the screenplay.[10] The two friends moved back to Boston for a year before the film finally went into production, directed by Gus Van Sant, and co-starring Damon, Affleck, Minnie Driver, and Robin Williams.[49] On its release, Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised the "smart and touching screenplay",[52] while Emanuel Levy of Variety found it "funny, nonchalant, moving and angry".[53] Jay Carr of The Boston Globe wrote that Affleck brought "a beautifully nuanced tenderness" to his role as the working-class friend of Damon's mathematical prodigy character.[54] Affleck and Damon eventually won both the Golden Globe and the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[11] Affleck has described this period of his life as "dreamlike": "It was like one of those scenes in an old movie when a newspaper comes spinning out of the black on to the screen. You know, '$100 Million Box Office! Awards!' "[31] He remains the youngest writer (at age 25) to ever win an Oscar for screenwriting.[49][55]

1998–2002: Leading man status

Affleck with Michael Bay and Liv Tyler at the Armageddon premiere in 1998

Armageddon, released in 1998, established Affleck as a viable leading man for Hollywood studio films. Good Will Hunting had not yet been released during the casting process and, after Affleck's screen test, director Michael Bay dismissed him as "a geek". He was convinced by producer Jerry Bruckheimer that Affleck would be a star,[26] but the actor was required to lose weight, become tanned, and get his teeth capped before filming began.[56] The film, where he starred opposite Bruce Willis as a blue-collar driller tasked by NASA with stopping an asteroid from colliding with Earth, was a box office success.[57] Daphne Merkin of The New Yorker remarked: "Affleck demonstrates a sexy Paul Newmanish charm and is clearly bound for stardom."[58] Later in 1998, Affleck had a supporting role as an arrogant English actor in the period romantic comedy Shakespeare in Love, starring his then-girlfriend Gwyneth Paltrow. Lael Loewenstein of Variety remarked that Affleck "does some of his very best work, suggesting that comedy may be his true calling,"[59] while Janet Maslin of The New York Times found him "very funny".[60]Shakespeare in Love won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, while the cast won the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast. Affleck then appeared as a small-town sheriff in the supernatural horror film Phantoms.[36] Stephen Holden of The New York Times wondered why actors like Affleck and Peter O'Toole had agreed to appear in the "junky" film: "Affleck's thudding performance suggests he is reading his dialogue for the first time, directly from cue cards."[61]

Affleck and Damon had an on-screen reunion in Kevin Smith's religious satire Dogma (after having appeared in Smith's previous films, Mallrats and Chasing Amy), which premiered at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival. Janet Maslin of The New York Times remarked that the pair, playing fallen angels, "bring great, understandable enthusiasm to Mr. Smith's smart talk and wild imaginings".[62] Affleck starred opposite Sandra Bullock in the romantic comedy Forces of Nature (1999), playing a groom whose attempts to get to his wedding are complicated by his free-spirited traveling companion. Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly remarked that Affleck "has the fast-break charm you want in a screwball hero,"[63] while Joe Leydon of Variety praised "his winning ability to play against his good looks in a self-effacing comic turn".[64] Affleck then appeared opposite Courtney Love in the little-seen ensemble comedy 200 Cigarettes (1999).[65]

Interested in a directorial career, Affleck shadowed John Frankenheimer throughout pre-production of the action thriller Reindeer Games (2000).[26][66] Frankenheimer, directing his last feature film, described Affleck as having "a very winning, likable quality about him. I've been doing this for a long time and he's really one of the nicest."[67] He starred opposite Charlize Theron as a hardened criminal, with Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times enjoying the unexpected casting choice: "Affleck often suggests one of the Kennedys playing Clark Kent ... He looks as if he has never missed a party or a night's sleep. He's game, though, and his slight dislocation works to the advantage of Reindeer Games."[68] He then had a supporting role as a ruthless stockbroker in the crime drama Boiler Room (2000).[66] A.O. Scott of The New York Times felt Affleck had "traced over" Alec Baldwin's performance in Glengarry Glen Ross,[69] while Peter Rainer of New York Magazine said he "does a series of riffs on Baldwin's aria, and each one is funnier and crueler than the next".[70] He then provided the voice of Joseph in the animated Joseph: King of Dreams.[71] In his last film role of 2000, Affleck starred opposite his girlfriend Paltrow in the romantic drama Bounce. Stephen Holden of The New York Times praised the "understated intensity and exquisite detail" of his performance: "His portrait of a young, sarcastically self-defined 'people person' who isn't half as confident as he would like to appear is close to definitive."[72]

Affleck reunited with director Michael Bay for the critically derided war drama Pearl Harbor (2001). He later characterized it as a film he did "for money – for the wrong reasons".[73] A.O. Scott of The New York Times felt Affleck and Kate Beckinsale "do what they can with their lines, and glow with the satiny shine of real movie stars".[74] But Todd McCarthy of Variety said, "the blandly handsome Affleck couldn’t convince that he’d ever so much as been turned down for a date, much less lost the love of his life to his best friend".[75] Affleck then parodied Good Will Hunting with Damon and Van Sant in Kevin Smith's Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back (2001),[76] made a cameo in the comedy Daddy and Them (2001),[77] and had a supporting role in the little-seen The Third Wheel (2002).[25] He portrayed the CIA analyst Jack Ryan in the thriller The Sum of All Fears (2002). Stephen Holden of The New York Times felt he was miscast in a role previously played by both Harrison Ford and Alec Baldwin: "Although Mr. Affleck can be appealing when playing earnest young men groping toward maturity, he simply lacks the gravitas for the role."[78] Affleck had an "amazing experience" making the thriller Changing Lanes (2002),[36] and later cited Roger Michell as someone he learned from as a director.[66][79] Robert Koehler of Variety described it as one of the actor's "most thoroughly wrought" performances: "The journey into a moral fog compels him to play more inwardly and thoughtfully than he ever has before."[80]

Affleck became more involved with television and film production in the early 2000s. He and Damon had set up Pearl Street Films in 1998,[81] named after the street that ran between their childhood homes.[82] Their next production company LivePlanet, co-founded in 2000 with Sean Bailey and Chris Moore, sought to integrate the Internet into mainstream television and film production.[82][83] LivePlanet's biggest success was the documentary series Project Greenlight, aired on HBO and later Bravo, which focused on first-time filmmakers being given the chance to direct a feature film. Project Greenlight was nominated for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Reality Program in 2002, 2004 and 2005.[84]Push, Nevada (2002), created, written and produced by Affleck and Bailey,[85] was an ABC mystery drama series that placed a viewer-participation game within the frame of the show.[86]Caryn James of The New York Times praised the show's "nerve, imagination and clever writing",[87] but Robert Bianco of USA Today described it as a "knock-off" of Twin Peaks.[88] The show was cancelled by ABC after seven episodes due to low ratings.[89] Over time, LivePlanet's focus shifted from multimedia projects to more traditional film production.[83] Affleck and his partners signed a film production deal with Disney in 2002; it expired in 2007.[90][91]

2003–2005: Career downturn and tabloid notoriety

While Affleck had been a tabloid figure for much of his career, and was named Sexiest Man Alive by People Magazine in 2002,[25] he was the subject of increased media attention in 2003 because of his relationship with Jennifer Lopez. By the end of the year, Affleck had become, in the words of GQ, the "world's most over-exposed actor".[92] His newfound tabloid notoriety coincided with a series of poorly received films.

Affleck visiting US Marines in Manama, Bahrain in 2003

The first of these was Daredevil (2003), in which Affleck starred as the blind superhero. Affleck was a longtime comic book fan, and had written a foreword for Kevin Smith's Guardian Devil (1999) about his love for the character of Daredevil.[93] The film was a commercial success,[94] but received a mixed response from critics. Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times said Affleck was "lost" in the role: "A big man, Mr. Affleck is shriveled by the one-dimensional role ... [Only his scenes with Jon Favreau have] a playful side that allows Mr. Affleck to show his generosity as an actor."[95] In 2014, Affleck described Daredevil as the only film he regretted making.[11] He next appeared as a low-ranking mobster in the romantic comedy Gigli (2003), co-starring Lopez. The film was almost uniformly panned,[96] with Manohla Dargis of the Los Angeles Times remarking that "Affleck doesn't have the chops or the charm to maneuver around (or past) bad material."[97] Yet Affleck has repeatedly defended director Marty Brest since the film's release, describing him as "one of the really great directors".[66][98] In his last film role of 2003, Affleck starred as a reverse engineer in the sci-fi thriller Paycheck (2003). Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian remarked on Affleck's "self-deprecating charm" and wondered why he could not find better scripts.[99] Manohla Dargis of the Los Angeles Times found it "almost unfair" to critique Affleck, given that he "had such a rough year".[100]

Affleck's poor critical notices continued in 2004 when he starred as a bereaved husband in the romantic comedy Jersey Girl, directed by longtime collaborator Smith. Stephen Holden of The New York Times described Affleck as an actor "whose talent has curdled as his tabloid notoriety has spread,"[101] while Joe Leydon of Variety found his onscreen role as a father "affecting".[102] Later that year, he starred opposite James Gandolfini in the holiday comedy Surviving Christmas. Holden noted in The New York Times that the film "found a clever way to use Ben Affleck's disagreeable qualities. The actor's shark-like grin, cocky petulance and bullying frat-boy swagger befit his character."[103] At this point, the quality of scripts offered to Affleck "was just getting worse and worse" and he decided to take a career break.[104] The Los Angeles Times published a piece on the downfall of Affleck's career in late 2004. The article noted that, unlike film critics and tabloid journalists, "few industry professionals seem to be gloating over Affleck's travails".[105]

2006–2015: Emergence as a director

After marrying actress Jennifer Garner in 2005, and welcoming their first child, Affleck began a career comeback in 2006. Following a starring role in the little-seen Man About Town and a minor role in the crime drama Smokin' Aces,[106][107] Affleck won acclaim for his performance as George Reeves in the noir biopic Hollywoodland. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone praised "an award-caliber performance ... This is feeling, nuanced work from an actor some of us had prematurely written off."[108] Geoffrey Macnab of The Guardian said he "beautifully" captured "the character's curious mix of charm, vulnerability and fatalism".[109] He was awarded the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor.[110] Also in 2006, he made a cameo in Smith's Clerks II.[111] Although they remain fans of each other's work,[112][113] Affleck and Smith have had little contact since the making of Clerks II.[114]

In 2007, Affleck made his feature film directorial debut with Gone Baby Gone, a crime drama set in a working-class Boston neighborhood, starring his brother Casey. Affleck co‑wrote the screenplay, based on the book by Dennis Lehane, with childhood friend Aaron Stockard, having first mentioned his intention to adapt the story in 2003.[115][116] It opened to enthusiastic reviews.[117] Manohla Dargis of The New York Times praised the film's "sensitivity to real struggle",[118] while Stephen Farber of The Hollywood Reporter described it as "thoughtful, deeply poignant, [and] splendidly executed".[119]

While Affleck intended to "keep a primary emphasis on directing" going forward in his career,[120] he acted in three films in 2009. In the ensemble romantic comedy He's Just Not That Into You, the chemistry between Affleck and Jennifer Aniston was praised.[121][122] Affleck played a congressman in the political thriller State of Play. Wesley Morris of The Boston Globe found him "very good in the film's silliest role,"[123] but David Edelstein of New York Magazine remarked of Affleck: "He might be smart and thoughtful in life [but] as an actor his wheels turn too slowly."[124] He had a supporting role as a bartender in the little-seen comedy film Extract.[125] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone described his performance as "a goofball delight",[126] while Manhola Dargis of The New York Times declared it "a real performance".[127] In 2010, Affleck starred in The Company Men as a mid-level sales executive who is made redundant during the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[128] David Denby of The New Yorker declared that Affleck "gives his best performance yet",[129] while Richard Corliss of Time found he "nails Bobby's plunge from hubris to humiliation".[130]

Affleck on the set of The Town in 2010

Following the modest commercial success of Gone Baby Gone, Warner Bros. developed a close working relationship with Affleck and offered him his choice of the studio's scripts.[7] He decided to direct the crime drama The Town (2010), an adaptation of Chuck Hogan's novel Prince of Thieves. He also co-wrote the screenplay and starred in the film as a bank robber. The film became a surprise box office hit, and gained further critical acclaim for Affleck.[131][132] A.O. Scott of The New York Times praised his "skill and self-confidence as a serious director,"[133] while Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times noted: "Affleck has the stuff of a real director. Everything is here. It's an effective thriller, he works closely with actors, he has a feel for pacing."[134] Also in 2010, Affleck and Damon's production company, Pearl Street Films, signed a first-look producing deal at Warner Bros.[135]

Affleck soon began work on his next directorial project, Argo (2012), for Warner Bros. Written by Chris Terrio and starring Affleck as a CIA operative, the film tells the story of the CIA plan to save six U.S. diplomats during the 1979 Iran hostage crisis by faking a production for a large-scale science fiction film. Anthony Lane of The New Yorker said the film offered "further proof that we were wrong about Ben Affleck".[136] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone remarked: "Affleck takes the next step in what looks like a major directing career ... He directs the hell out of it, nailing the quickening pace, the wayward humor, the nerve-frying suspense."[137] A major critical and commercial success,[138]Argo won the Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, and BAFTA Award for Best Picture.[139] The cast won the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast. Affleck himself won the Golden Globe Award, Directors Guild of America Award, and BAFTA Award for Best Director, becoming the first director to win these awards without a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Director.[140]

The following year Affleck played a romantic lead in Terrence Malick's experimental drama To the Wonder. Malick, a close friend of Affleck's godfather, had first met with the actor in the 1990s to offer advice about the plot of Good Will Hunting.[141] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian enjoyed "a performance of dignity and sensitivity,"[142] while The New Yorker 's Richard Brody described Affleck as "a solid and muscular performer" who "conveys a sense of thoughtful and willful individuality".[143] Affleck's performance as a poker boss was considered a highlight of the poorly-reviewed thriller Runner Runner (2013).[144][145] Betsy Sharkey of the Los Angeles Times remarked that it was "one killer of a character, and Affleck plays him like a Bach concerto—every note perfectly played."[146] Also in 2013, Affleck hosted the sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live for the fifth time since 2000, becoming a member of the Five Timers Club.[147] He then pushed back production on his own directorial project to star as a husband accused of murder in David Fincher's psychological thriller Gone Girl (2014).[148] Fincher cast him partly because he understood what it felt like to be misrepresented by tabloid media: "What many people don’t know is that he's crazy smart, but since he doesn’t want that to get awkward, he downplays it. I think he learned how to skate on charm."[149] David Edelstein of New York Magazine noted that Fincher's controlled style of directing had a "remarkable" effect on Affleck's acting: "I never thought I’d write these words, but he carries the movie. He's terrific."[150] Justin Chang of Variety found Affleck "perfectly cast": "It's a tricky turn, requiring a measure of careful underplaying and emotional aloofness, and he nails it completely."[151] In 2015, Affleck and Damon's Project Greenlight was resurrected by HBO for one season.[152]

2016–present: Batman role and continued directing

Given Affleck's growing reputation as a filmmaker, his decision to star as Batman in the 2016 superhero film Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was regarded by Anthony Lane of The New Yorker as a "backward step into the realm of beefcake",[153] and by Dave Itzkoff of The New York Times as "a somewhat bewildering choice".[154] Although the casting choice was met with intense fan backlash,[155] Affleck's performance ultimately earned a positive reception. Andrew Barker of Variety found him "a winningly cranky, charismatic presence,"[156] while Brian Truitt of USA Today enjoyed his "strong" and "surprisingly emotional" take on the character.[157] Affleck reprised his role as Batman twice, making a cameo appearance in Suicide Squad (2016)[158] and starring in Justice League (2017). Each of these films are part of the DC Extended Universe (DCEU).[159]Justice League drew mixed opinions from critics; Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter wrote that Affleck "looks like he'd rather be almost anywhere else but here."[160][161]

In addition to his various Batman commitments, Affleck appeared in two other films in 2016. He starred as an autistic accountant in the action thriller The Accountant (2016), which was an unexpected commercial success.[162] Peter Debruge of Variety felt Affleck's "boy-next-door" demeanor – "so normal and non-actorly that most of his performances feel like watching one of your buddies up on screen" – was "a terrific fit" for the role.[163] Stephen Holden of The New York Times wondered why Affleck, "looking appropriately dead-eyed and miserable," committed himself to the film.[164]Live by Night, which Affleck wrote, directed, co-produced, and starred in, was released in late 2016.[165] Adapted from Dennis Lehane's novel of the same name, the Prohibition-era gangster drama received largely unenthusiastic reviews and failed to recoup its $65 million production budget.[166] David Sims of The Atlantic described it as "a fascinating mess of a movie" and criticized Affleck's "stiff, uncomfortable" performance. He noted that one of the last action scenes "is so wonderfully staged, its action crisp and easy to follow, that it reminds you what skill Affleck has with the camera".[167] In October 2016, Affleck and Damon made a one-off stage appearance for a live reading of the Good Will Hunting screenplay at New York's Skirball Theater.[168]

Affleck did not work in 2017; he stepped down as director and writer of The Batman, citing an unmanageable workload,[169][170] and withdrew from Netflix's Triple Frontier, citing personal reasons.[171] He rejoined Triple Frontier, directed by J. C. Chandor, when filming was moved to early 2018. Oscar Isaac, Garrett Hedlund and Charlie Hunnam co-star in the drug-trafficking thriller.[171] Later in 2018, he filmed a role opposite Anne Hathaway in Dee Rees's political thriller The Last Thing He Wanted.[172] Both films are expected to be released in 2019.

Humanitarian work

Eastern Congo Initiative

Affleck in 2011, testifying before the House Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health and Human Rights

After travelling in the region between 2007 and early 2010, Affleck and Whitney Williams co-founded the nonprofit organization Eastern Congo Initiative in 2010.[173][174] ECI acts as a grant maker for Congolese-led, community-based charities.[175] It offers training and resources to cooperatives of Congolese farmers while leveraging partnerships with companies including Theo Chocolate and Starbucks.[176][177] ECI also aims to raise public awareness and drive policy change in the United States.[178]

Affleck has written op-eds about issues facing eastern Congo for the Washington Post,[179][180]Politico,[181] the Huffington Post,[182] and Time.[183] He has appeared as a discussion panelist at many events, including at the Center for Strategic and International Studies,[184] the Global Philanthropy Forum,[185] and the Clinton Global Initiative.[186] During visits to Washington D.C., Affleck has testified before the House Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health and Human Rights,[187] the House Armed Services Committee,[188] the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,[189] and the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Projects.[190]

Other charitable causes

Affleck is a supporter of the A-T Children's Project. While filming Forces of Nature in 1998, Affleck befriended ten-year-old Joe Kindregan (1988–2015), who had the rare disease ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T), and his family.[191] He became actively involved in fundraising for A-T,[192][193] and he and Kindregan testified before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health & Human Services, and Education in 2001, asking senators to support stem-cell research and to double the budget of the National Institutes of Health.[191] In 2007, Affleck was the keynote speaker at Kindregan's high school graduation ceremony in Fairfax, Virginia.[194] Kindregan appeared as an extra in Argo (2012).[195] In 2013, in celebration of Kindregan's 25th birthday and "15 years of friendship with Joe and his family," Affleck and Garner matched donations made to the A-T Children's Project.[196] Affleck appeared in CinemAbility (2013), a documentary film which explores Hollywood's portrayals of people with disabilities.[197]

Affleck speaking at a Feeding America rally in 2009

As part of USO-sponsored tours, Affleck visited marines stationed in the Persian Gulf in 2003,[198] and troops at Germany's Ramstein Air Base in 2017.[199] He is a supporter of Paralyzed Veterans of America.[200] He filmed public service announcements for the organization in both 2009 and 2014.[201][202] He has also volunteered on behalf of Operation Gratitude.[203][204]

Affleck is a member of Feeding America's Entertainment Council.[205] He made an appearance at the Greater Boston Food Bank in 2007,[206] and at a Denver food bank in 2008.[207] Affleck spoke at a Feeding America rally in Washington D.C. in 2009,[208] and filmed a public service announcement for the charity in 2010.[209] Affleck and Ellen DeGeneres launched Feeding America's Small Change Campaign in 2011.[210] Also that year, he and Howard Graham Buffett co-wrote an article for The Huffington Post, highlighting the "growing percentage of the food insecure population that is not eligible for federal nutrition programs".[211]

In March 2018, he and Damon announced that they would adopt the Inclusion rider agreement to promote cast and crew diversity in all future projects through their Pearl Street Films.[212]

Politics

Political views

Affleck has described himself as "moderately liberal."[213] He was raised in "a very strong union household".[214] In 2000, he spoke at a rally at Harvard University in support of an increased living wage for all workers on campus; his father and stepmother worked as janitors at the university.[14] He later narrated a documentary, Occupation (2002), about a sit-in organized by the Harvard Living Wage Campaign.[215] Affleck and Senator Ted Kennedy held a press conference on Capitol Hill in 2004, pushing for an increase in the minimum wage.[216] He spoke at a 2007 press conference at Boston's City Hall in support of SEIU's unionization efforts for the city's low-paid hospital workers.[217] During the Writers' Strike in 2008, Affleck voiced support for the picketers.[218] He criticized the Bush tax cuts on many occasions.[219][220][221]

Affleck is pro-choice. In a 2000 interview, he stated that he believes "very strongly in a woman's right to choose".[21] In 2012, he supported the Draw the Line campaign, describing reproductive rights as "fundamental".[222] Affleck was a longtime supporter of legalizing gay marriage, saying in 2004 that he hoped to look back on the marriage debate "with some degree of embarrassment for how antiquated it was".[223] Also that year, he remarked that it was "outrageous and offensive" to suggest members of the transgender community were not entitled to equal rights.[224] He appeared alongside his gay cousin in a 2005 Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays print advertising campaign.[225] Affleck filmed a public service announcement for Divided We Fail, a nonpartisan AARP campaign seeking affordable, quality healthcare for all Americans, in 2007.[226]

Affleck appeared at a press conference with New York Senator Chuck Schumer in 2002, in support of a proposed Anti-Nuclear Terrorism Prevention Act.[227] In 2003, he criticized the "questionable and aggressive" use of the Patriot Act and the resulting "encroachments on civil liberties".[219] A reporter for The Washington Post overheard Affleck denouncing the Israeli invasion of Gaza at a Washington party in 2009.[228]Steven Clemons, a participant in the conversation, said Affleck listened "to alternative takes ... What Affleck spoke about that night was reasoned, complex and made a lot of sense."[229] Later that year, in a New York Times interview, Affleck remarked that his views were closer to those of the Israeli Labor Party than Likud.[230]

Affleck with Russ Feingold and Secretary of State John Kerry in February 2014

During the 2008 presidential campaign, Affleck expressed concerns about conspiracy theories claiming Barack Obama was an Arab or a Muslim: "This prejudice that we have allowed to fester in this campaign ... the acceptance of both of those things as a legitimate slur is really a problem."[231][232] In 2012, he praised Senator John McCain's leadership in defending Huma Abedin against anti-Muslim attacks.[233][234] Affleck engaged in a discussion about the relationship between liberal principles and Islam during a 2014 appearance on Real Time with Bill Maher.[235] In a 2017 Guardian interview, he said: "I strongly believe that no one should be stereotyped on the basis of their race or religion. It’s one of the most fundamental tenets of liberal thought."[236]

Affleck is a supporter of the Second Amendment.[213] In a 2012 interview, he said he owns several guns, both for skeet shooting and for the protection of his family.[7]

Affleck appeared alongside then-Senator Barack Obama at a 2006 rally in support of Proposition 87, which sought to reduce petroleum consumption in favor of alternative energy.[237] He appeared in a global warming awareness video produced by the Center for American Progress Action Fund in 2007.[238] Also that year, Affleck admitted he was not "particularly good at being green" while, in 2014, he named "a 1966 Chevelle" as his guilty pleasure.[239][11] In 2016, Affleck filmed an endorsement for Rezpect Our Water, an online petition to stop construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.[240]

Democratic Party activism

Affleck registered to vote as a Democrat in 1992, and has campaigned on behalf of several Democratic presidential nominees. He supported Al Gore in the final weeks of the 2000 presidential campaign, attending rallies in California,[241] Pennsylvania,[242] and Florida.[243] However, Affleck was unable to vote due to a registration issue in New York, where he was then residing, and later joked, "I'm going to vote twice next time, in true Boston fashion."[244]

Affleck speaking at a John Kerry rally in Zanesville, Ohio in 2004

Affleck was involved in the 2004 presidential campaign of John Kerry. During the Democratic National Convention in Boston, he spoke to many delegations, appeared on political discussion shows, and attended fundraising events.[245][246] Affleck took part in a voter registration public service announcement,[247] and traveled with Kerry during the opening weekend of his Believe in America Tour, making speeches at rallies in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio.[248]

Affleck appeared alongside then-Senator Barack Obama at a 2006 rally, introducing him as "the most galvanizing leader to come out of either party, in my opinion, in at least a decade".[237] He donated to Obama's presidential campaign in 2007,[249] and hosted two fundraisers for the candidate during the 2008 Democratic Primary.[250][251] Affleck urged voters to "help make history" in a MoveOn.org campaign,[252] and made several appearances during the 2008 Democratic National Convention.[253] In the week of the presidential election, he appeared on Saturday Night Live to jokingly endorse Senator John McCain.[254] Affleck did not actively campaign for Obama's reelection in 2012,[7] but stated: "I like the president, I’m going to vote for the president."[255]

In 2000, Affleck introduced Senate candidate Hillary Clinton at a Cornell University rally and helped fundraise for her campaign.[256] Affleck, who first met the Clintons at Camp David in 1998,[257] pointed to the First Lady's work with children, women and "working families".[258] He supported Obama during the 2008 Democratic Primary, noting that Clinton had "moved toward the center" during the campaign.[239] Affleck supported Clinton during the 2016 Democratic Primary.[259] He recorded a New Hampshire voter public service announcement,[260] and was named by the Clinton campaign as a "Hillblazer" – one of 1,100 individuals who had contributed or raised at least $100,000.[261] The Center for Responsive Politics reported that he raised $149,028.[262]

In 2002, Affleck donated to Dick Gephardt's Congressional campaign,[263] and appeared in campaign literature for former classmate Marjorie Decker, running as a city councillor in Massachusetts.[264] He made donations to the presidential campaigns of both Dennis Kucinich and Wesley Clark in 2003.[265] In 2005, he donated to the campaign fund of Deval Patrick, a candidate for Governor of Massachusetts.[266] In 2006, Affleck contributed to Cory Booker's Newark mayoral campaign,[267] and introduced Congressmen Joe Courtney and Chris Murphy at rallies in Connecticut.[268] He donated to the 2008 Congressional campaign of Pennsylvania's Patrick Murphy,[269] and to the 2010 Senate campaign of Kirsten Gillibrand.[263] Affleck hosted a 2012 fundraiser for Senate candidate Elizabeth Warren,[270] endorsed her in a Progressive Change Campaign Committee video,[271] and made a campaign donation.[263] In 2013, he hosted a fundraiser for Senate candidate Cory Booker,[272] and made donations to the campaigns of both Booker and Alison Lundergan Grimes.[273][274] He donated to the campaign of Senate candidate Kamala Harris in 2015, and to the Congressional campaign of Melissa Gilbert in 2016.[263]

In the early 2000s, Affleck often expressed an interest in running for political office one day,[244] but since 2007, he has denied any political ambitions and spoken repeatedly about the need for campaign finance reform.[236][239][275] In 2005, The Washington Post reported that Virginia Democrats were trying to persuade Affleck to run as a Senate candidate.[276] His publicist dismissed the rumor.[277] In 2012, political pundits and Democratic strategists including Bob Shrum and Tad Devine speculated that Affleck was considering running for a Massachusetts Senate seat.[278] Affleck denied the rumor,[279] and joked that he "also won't be throwing my hat in the ring to run the U.N."[280]

Personal life

Relationships and family

Affleck began dating actress Gwyneth Paltrow in October 1997 after meeting at a Miramax dinner,[281] and they later worked together on Shakespeare in Love (1998). Although they first broke up in January 1999, months later, Paltrow persuaded Affleck to co-star with her in Bounce (2000) and they soon resumed their relationship.[282] They separated again in October 2000.[283] In a 2015 interview, Paltrow said she and Affleck remain friends.[281]

Affleck had an 18-month relationship with actress/singer Jennifer Lopez from 2002 to 2004. They began dating in July 2002, after meeting on the set of Gigli (2003), and later worked together on the "Jenny from the Block" music video and Jersey Girl (2004).[284][285] Their relationship received extensive media coverage.[286] They became engaged in November 2002,[287] but their planned wedding on September 14, 2003, was postponed with four days' notice because of "excessive media attention".[288] They broke up in January 2004.[289] Lopez later described the split as "my first real heartbreak" and attributed it in part to Affleck's discomfort with the media scrutiny.[290][291] In 2013, Affleck said he and Lopez occasionally "touch base".[292]

Affleck began dating actress Jennifer Garner in mid-2004,[293] having established a friendship on the sets of Pearl Harbor (2001) and Daredevil (2003).[294] They were married on June 29, 2005, in a private Turks and Caicos ceremony.[295]Victor Garber, who officiated the ceremony, and his partner, Rainer Andreesen, were the only guests.[296] They announced their intention to divorce in June 2015,[297] and filed legal documents in April 2017.[298]

Affleck and Garner have three children together: daughters Violet Anne (b. December 2005), Seraphina "Sera" Rose Elizabeth (b. January 2009),[299][300] and son Samuel "Sam" Garner (b. February 2012).[301] In their divorce filings, Affleck and Garner sought joint physical and legal custody of their children.[298] While Affleck believes paparazzi attention is "part of the deal" of stardom, he has spoken out against paparazzi interest in his children.[302] He has called for legislation to require paparazzi to maintain a certain distance from children and to blur their faces in published photos.[11]

Affleck dated television producer Lindsay Shookus from mid-2017 to mid-2018.[303][304]

Alcoholism

Affleck at the 2008 World Series of Poker in Las Vegas, Nevada

Affleck has struggled with alcoholism for much of his adult life.[305] In a 1998 interview, he said he had quit drinking alcohol because it was "dangerous" for him.[306] In 2001, he completed a 30-day residential rehabilitation program for alcohol abuse. When the story leaked to the press, a spokesperson said the actor "decided that a fuller life awaits him without alcohol".[307] Affleck later described the rehab stay as a "pre-emptive strike" given his family's history of alcoholism.[308]

In March 2017, Affleck completed a residential rehabilitation program,[309] confirming in a statement that he had received "treatment for alcohol addiction; something I've dealt with in the past and will continue to confront".[310] In August 2018, he entered another residential treatment facility.[311]

Professional gambling

Affleck won the 2004 California State Poker Championship, taking home the first prize of $356,400 and qualifying for the 2004 World Poker Tour final tournament.[312] He was one of many celebrities, along with Tobey Maguire and Leonardo DiCaprio, rumored to have taken part in Molly Bloom's high-stake poker games at The Viper Room in the mid-2000s.[313] In 2014, Affleck was asked to refrain from playing blackjack at the Hard Rock Hotel in Las Vegas, after a series of wins aroused suspicion that he was counting cards, which is a legal gambling strategy frowned upon by casinos.[314] Affleck has repeatedly denied tabloid reports of a gambling addiction.[315][316]

Religion

In a 2003 interview, Affleck described himself as a "lapsed" Protestant,[317][7] and later listed the Gospel of Matthew as one of the books that made a difference in his life.[318] As infants, each of his three children were baptized as members of the United Methodist Church.[319] In 2015, he began attending Methodist church services in Los Angeles.[320][321]

Ancestry

Much of the Affleck’s ancestry is English, Irish, Scottish and German.[322] Affleck’s maternal great-great grandfather, Heinrich Boldt, who is also known for the discovery of the Curmsun Disc, emigrated from Prussia in the late 1840s.[323][324]

Affleck appeared on the PBS genealogy series Finding Your Roots in 2014. When told that an ancestor of his had been a slave owner in Georgia, Affleck responded: "God. It gives me kind of a sagging feeling to see a biological relationship to that. But, you know, there it is, part of our history ... We tend to separate ourselves from these things by going like, 'It's just dry history, and it's all over now'."[325] Leaked emails from the 2015 Sony email hacking scandal showed that, after filming, Affleck's representative emailed the documentary maker to say the actor felt "uncomfortable" about the segment, which was not included in the final broadcast.[326] PBS denied the claim that it had censored the show at Affleck's behest, and the show's host, professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., stated "we focused on what we felt were the most interesting aspects of his ancestry".[326]

TRL incident

In 2017, actress and former Total Request Live (TRL) host Hilarie Burton retweeted a video clip from TRL Uncensored, in which Burton is seen recalling how Affleck "wraps his arm around me, and comes over and tweaks my left boob" during an appearance in 2003. Burton said, "I didn't forget [about it]." Affleck responded on Twitter, "I acted inappropriately toward Ms. Burton and I sincerely apologize."[327]

Filmography and awards

Affleck has appeared in more than 50 films, and won many accolades throughout his career as an actor, writer, and director. He first gained recognition as a writer when he won the Golden Globe and the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Good Will Hunting (1997), which he co-wrote with Matt Damon.[328] As an actor, he received a Golden Globe nomination for his performance in Hollywoodland (2006). The film Argo (2012), which he directed, co-produced, and starred in, won him the Golden Globe Award, BAFTA, and Directors Guild Award for Best Director, as well as the Golden Globe Award, BAFTA, the Producers Guild Award, and the Academy Award for Best Picture.[139]

References

^ Radloff, Jessica (February 15, 2015). "You Won't Believe Shonda Rhime's Method for Knowing Whether a Story Works". Glamour. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ He is listed as "Benjamin G. Affleckbold"; born on August 15, 1972 in Alameda County according to the State of California. California Birth Index, 1905–1995. Center for Health Statistics, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, California.

^ Casey, Nora Sørena. "Ben Affleck – American actor, writer, and director". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

^ abc McCarthy, Kevin (1997). "Cinezine – Frank Discussions With Ben Affleck". View Askew Productions Official Website. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ Morris, Wesley (September 15, 2010). "With New Film, Affleck Ties Boston Knot Tighter". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

^ "Tidbits, One Ringtailed". Harvard Magazine. March 1, 2010. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ abcdefgh Galloway, Stephen (November 17, 2011). "Confessions of Ben Affleck". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

^ "Christopher Anne Affleck – Events – 20th Anniversary Luminaries". Breakthrough Greater Boston. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ abcde Lidz, Franz (September 10, 2000). "I Bargained With Devil for Fame". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ ab Weinraub, Bernard (December 1, 1999). "Playboy Interview: Ben Affleck". Playboy. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017 – via HighBeam Research.

^ abcdefghi Fleming, Michael (January 27, 2014). "Ben Affleck on Argo, His Distaste For Politics and the Batman Backlash". Playboy. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

^ ab Leiby, Richard (May 10, 2002). "The 'Sum' and The Substance". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ ab Atkinson, Kim (May 15, 2006). "Casey, the Other Affleck". Boston. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ ab Powell, Alvin (May 11, 2000). "Damon, Affleck Rally to Living Wage Cause". Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on March 13, 2005. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Sorbello, Donna (January 27, 2012). "Father Of The Boston Theatre Scene". Actors' Equity Association. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ ab Schneider, Karen (February 21, 2000). "Cover Story: Good Time Hunting – Vol. 53 No. 7". People. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Shanahan, Mark (March 15, 2017). "Ben Affleck has Struggled with Alcohol for a Long Time". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ "Episode 767 - Casey Affleck". WTF with Marc Maron Podcast. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

^ "Interview: Ben Affleck, Actor". The Scotsman. September 19, 2010. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

^ McGinty, Kate (January 5, 2013). "Palm Springs Film Festival: Ben Affleck Spit on Me". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ ab Reiter, Amy (November 8, 2000). "Ben Affleck: "I Hope Nader Can Still Sleep"". Salon. p. 6(7), 36–100. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ Berk, Sheryl (July 2002). "Ben Affleck on Stardom, Settling Down, and Working with Best Buddy Matt Damon". Biography Magazine. pp. 36–100.

^ Roberts, Sheila (August 12, 2013). "Casey Affleck Talks Ain't Them Bodies Saints, Working with Rooney Mara, His Relationship with His Brother, I'm Still Here, and More". Collider. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ Stern, Marlow (December 2, 2013). "Casey Affleck, Star of 'Out of the Furnace,' on His Hollywood Struggles". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ abcd Miller, Samantha (December 2, 2002). "Cover Story: Sexiest Man Alive…Ben Affleck – Vol. 58 No. 23". People. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ abcd Wallace, Amy (March 7, 1999). "Opportunity Knocked at Every Turn". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Garratt, Sheryl (May 30, 2008). "Casey Affleck's Time to Shine". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ Booth, William (October 17, 2007). "Bond of Brothers". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ ab Mitchell, Russ (September 12, 2010). "Ben Affleck: Insecurity, Fear Good Motivators". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ abc Sischy, Ingrid (April 16, 2014). "New Again: Ben Affleck". Interview. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ abc Rader, Dotson (October 10, 2007). "Ben Affleck: 'I Have a Strong Sense of Where I Want to Go'". Parade Magazine. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "Interview With 'The Adjustment Bureau' Star Matt Damon". CNN. March 3, 2011. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "PrimeTime: The Real Ben Affleck". ABC News. November 16, 2002. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ Edwards, Sian (October 29, 2012). "Enter Ben's World". Global Citizen Magazine. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ Singh, Ajay (January 15, 2013). "Did Ben Affleck Major in Middle Eastern Studies From Oxy?". Eagle Rock Patch. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ abcdefghij Riley, Jenelle (December 23, 2010). "Ben Affleck Knows His Way Around the 'Town'". Backstage. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ Sherman, Paul (May 1, 2008). Big Screen Boston: From Mystery Street to The Departed and Beyond. Black Bars Publishing. ISBN 978-0977639748. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

^ "Profiles of Ex-Couple Ben Affleck, Jennifer Lopez". CNN. January 24, 2004. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Davis, Edward (February 18, 2013). "Watch: Ben Affleck's Directorial Debut 'I Killed My Lesbian Wife, Ηung Ηer On A Μeathook & Νow I Have A Three-Picture Deal With Disney' [Short Film]". IndieWire. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ "School Ties, Ben Affleck". Entertainment Weekly. January 14, 2007. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Stern, Marlow (September 24, 2013). "'Dazed and Confused' 20th Anniversary: 20 Craziest Facts About the Cult Classic". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

^ Stern, Marlow (September 24, 2013). "'Dazed and Confused' Director Richard Linklater on Its 20th Anniversary". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ Spitz, Marc (December 27, 2013). "An Oral History of 'Dazed and Confused'". Maxim. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ Holden, Stephen (September 27, 1996). "A Major in Parties and a Minor in Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ Maslin, Janet (April 4, 1997). "Chasing Amy (1997)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Gleiberman, Owen (April 4, 1997). "Movie Review: 'Chasing Amy' (1997)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ McCarthy, Todd (January 30, 1997). "Review: Going All the Way". Variety. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Maslin, Janet (January 27, 1997). "Independent Films Have Their Sundance Night". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

^ abcd Nanos, Janelle (January 2013). "Good Will Hunting: An Oral History". Boston Magazine. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

^ Shone, Tom (February 26, 2011). "The Double Life of Matt Damon". The Times. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

^ Goldman, William (May 2, 2000). "Good Will Hunting: the Truth". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Maslin, Janet (December 5, 1997). "Good Will Hunting: Logarithms and Biorhythms Test a Young Janitor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Levy, Emanuel (November 30, 1997). "Review: Good Will Hunting". Variety. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Carr, Jay (December 25, 1997). "'Will' Has its Way". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Malla, Pasha (February 26, 2016). "What Makes a Great Script? The Oscar Nominees for Best Original Screenplay". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on February 27, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

^ Fennessey, Sean (June 27, 2011). "An Oral History of Transformers Director Michael Bay". GQ. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "Armageddon (1998) – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Merkin, Daphne (July 20, 1998). "The Film File: Armageddon". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 5, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Loewenstein, Lael (December 6, 1998). "Review: 'Shakespeare in Love'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Maslin, Janet (December 11, 1998). "Shakespeare in Love (1998)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Holden, Stephen (January 23, 1998). "Phantoms: A Monster Hungry for Attention". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Maslin, Janet (October 4, 1999). "Dogma: There's Devilment Afoot: 2 Fallen Angels Want Back In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Gleiberman, Owen (March 26, 1998). "Forces of Nature (1999)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Leydon, Joe (March 14, 1999). "Review: 'Forces of Nature'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ "200 Cigarettes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ abcd Nashawaty, Chris (September 9, 2010). "Ben Affleck Calls The Shots". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Peretz, Evgenia. "Let's Try It Ben's Way". Vanity Fair (October 1999). p. 262.

^ Mitchell, Elvis (February 25, 2000). "Reindeer Games: Santa Would Surely Be Useful Right Now". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Scott, A.O. (February 18, 2000). "Boiler Room (2000)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Rainer, Peter (February 28, 2000). "Perfect Pitch". New York. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Leydon, Joe (November 6, 2000). "Review: 'Joseph: King of Dreams'". Variety. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

^ Holden, Stephen (November 17, 2000). "Bounce (2000)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Shone, Tom (November 6, 2012). "Ben Affleck Talks About His New Film, Argo". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Scott, A.O. (May 25, 2001). "Pearl Harbor: War Is Hell but Very Pretty". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ McCarthy, Todd (May 23, 2001). "Review:Pearl Harbor". Variety. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Mitchell, Elvis (August 24, 2001). "Jay And Silent Bob Strike Back: Hitchhiking in a Hurry: What Does That Tell You?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Cockrell, Eddie (August 28, 2001). "Review: Daddy and Them". Variety. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Holden, Stephen (May 31, 2002). "The Sum of all Fears: Terrorism That's All Too Real". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ "Interview: Out on The Town with Ben Affleck". Emirates 24/7. Reuters. December 27, 2010. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Koehler, Robert (April 5, 2002). "Review: 'Changing Lanes'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 14, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Petrikin, Chris (July 27, 1998). "Pearl Street Taps Kubena". Variety. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ ab Holson, Laura M. (May 27, 2001). "Bidding To Be Moguls Of a Risky Business- Page 2". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

^ ab Holson, Laura (August 5, 2002). "Affleck and Damon Find Real-Life Obstacles to Their Media Venture". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

^ Barile, Louise A. (August 21, 2002). "Ben & Matt To Give Second 'Greenlight'". People. Archived from the original on April 17, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

^ Gallo, Phil (September 11, 2002). "Review: 'Push, Nevada'". Variety. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Connolly, Kelly (October 10, 2002). "Ben Affleck & Matt Damon". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

^ James, Caryn (September 17, 2002). "Sex in Unison: Just One Quirk Among Many". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Bianco, Robert (September 16, 2002). "Quirky 'Push' is Truly a Mystery Within a Mystery". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Friedman, Wayne (October 14, 2002). "Cancellation of Push, Nevada Miffs Marketers". Advertising Age. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

^ Fleming, Michael (August 5, 2002). "Planet in Disney Pic Prod'n Orbit". Variety. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Fleming, Michael (January 30, 2008). "LivePlanet Film Unit Takes Final Bow". Variety. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "The Verge: Building a New Ben". GQ. January 4, 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

^ Downey, Ryan J. (June 24, 2002). "Affleck, Garner Open Up About 'Daredevil'". MTV. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

^ "Ben Affleck Movie Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

^ Mitchell, Elvis (February 14, 2003). "Daredevil: Blind Lawyer As Hero In Red". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ "Gigli (2003)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

^ Dargis, Manohla (August 1, 2003). "Gigli's Faults: More Than a Couple". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Shone, Tom (November 6, 2012). "Ben Affleck Talks about His New Film, Argo". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 2, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

^ Bradshaw, Peter (January 15, 2004). "Paycheck". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Dargis, Manohla (December 24, 2003). "Director Woo Falls Down on the Job with 'Paycheck'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

^ Holden, Stephen (March 26, 2004). "How to End a Career: Take a Baby to a News Conference". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Leydon, Joe (March 15, 2004). "Jersey Girl". Variety. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Holden, Stephen (October 22, 2004). "You Can't Go Home, or Perhaps You Just Shouldn't". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Silverman, Stephen M. (November 29, 2006). "Ben Affleck: 'I Would Love' More Kids". People. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Masters, Kim (October 27, 2004). "Ben's Big Fall". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ "Man About Town – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

^ Siegel, Tatiana (January 2, 2014). "Chris Pine Reveals His Politics Amid High-Risk 'Jack Ryan' Play". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

^ Travers, Peter (September 7, 2006). "Hollywoodland: Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

^ Macnab, Geoffrey (November 7, 2006). "Come Fly With Me". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ "HFPA – Awards Search". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

^ Bowles, Scott (July 21, 2006). "Inspired Moments are Too Few in Clerks II". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ "Ben Affleck – Movies That Made Me, Movies That Made Me". BBC Radio 1. January 24, 2017. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

^ Gonzalez, Umberto (October 6, 2016). "Why Kevin Smith Prefers Ben Affleck's Batman to 'Mr. Mom' Michael Keaton's". TheWrap. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Stern, Marlow (September 9, 2014). "Kevin Smith's Marijuanaissance: On 'Tusk,' 'Falling Out' with Ben Affleck, and 20 Years of 'Clerks'". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

^ Archerd, Army (May 1, 2003). "Lopez Flies to Affleck During 'Life' Breaks". Variety. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "Interviews: Ben Affleck Talks Paycheck". ComingSoon. December 15, 2003. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "Gone Baby Gone (2007)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Dargis, Manohla (October 19, 2007). "Human Frailty and Pain on Boston's Mean Streets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Farber, Stephen (September 4, 2007). "Gone Baby Gone". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Stein, Ruthe (October 5, 2007). "Ben Affleck Behind the Camera in 'Gone Baby Gone'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Gleiberman, Owen (February 4, 2009). "He's Just Not That Into You". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Burr, Ty (February 6, 2009). "Love and Star Power Mingle in 'He's Just Not That Into You'". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Morris, Wesley (April 17, 2009). "'State of Play' Chases Juicy Story and Lionizes Print Reporters". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Edelstein, David (April 17, 2009). "State of Play". New York. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Lemire, Christy (August 31, 2009). "Review: 'Extract' Tastes Too Bland". Salon. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

^ Travers, Peter (September 3, 2009). "Extract". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 8, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Dargis, Manohla (September 3, 2009). "Working in the Salt Mines: The Boss's View". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ "Affleck: When 'Company Men' Lose A Firm Footing". NPR. December 21, 2010. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Denby, David (December 20, 2010). "Roundup". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Corliss, Richard (January 22, 2011). "The Company Men: You're Hired!". Time. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Finke, Nikki (September 19, 2010). "Ben Affleck's 'The Town' Surprises For #1; 'Easy A' #2, 'Devil' #3, 'Alpha & Omega' #5". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ "The Town (2010)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 12, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

^ Scott, A.O. (September 16, 2010). "Bunker Hill to Fenway: A Crook's Freedom Trail". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Ebert, Roger (September 15, 2010). "The Town". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ McNary, Dave (February 17, 2010). "Affleck, Damon in Talks with Warner Bros". Variety. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Lane, Anthony (October 15, 2012). "Film Within a Film". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Travers, Peter (October 11, 2012). "Argo". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ McClintock, Pamela (November 2, 2013). "Box Office Milestone: Ben Affleck's 'Argo' Hitting $200 Million Worldwide". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ ab Thompson, Anne (January 27, 2013). "SAG Awards: With Critics Choice, Globes, PGA and SAG Wins, 'Argo' Now Challenges 'Lincoln'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

^ Feinberg, Scott (January 16, 2013). "How to Fix Oscar's Baffling Snub of Ben Affleck (Analysis)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Lyttelton, Oliver (January 6, 2011). "How Do You Like That? Terrence Malick Gave Ben Affleck & Matt Damon Notes On 'Good Will Hunting'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 21, 2013). "To the Wonder". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Brody, Richard (April 10, 2013). "The Cinematic Miracle of 'To The Wonder'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 13, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Hornaday, Ann (October 3, 2013). "Runner Runner Review: Talented Cast, Director Deal a Weak Hand". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Barker, Andrew (September 25, 2013). "Film Review: Runner Runner". Variety. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Sharkey, Betsy (October 3, 2013). "'Runner Runner' Runs Hot, Cold with Ben Affleck, Justin Timberlake". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Cappadona, Bryanna (May 16, 2013). "Watch Ben Affleck's Top Sketches from 'Saturday Night Live'". Boston. Archived from the original on April 17, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

^ Pierce, Nev (September 27, 2014). "David Fincher on Gone Girl: 'Bad Things Happen in This Movie…'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 17, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Robinson, Joanna (September 18, 2014). "Gone Girl Director David Fincher Cast Ben Affleck After Googling His Nervous Smile". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Edelstein, David (October 1, 2014). "David Fincher Puts Ben Affleck's Evasiveness to Good Use in Gone Girl". New York. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Chang, Justin (September 21, 2014). "Film Review: 'Gone Girl'". Variety. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

^ Thompson, Anne (October 12, 2015). "The Unsinkable Effie Brown Makes HBO's 'Project Greenlight' a Must-See: "I'm not his favorite person"". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Lane, Anthony (April 4, 2016). "In "Batman v Superman," Nobody Wins". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

^ Itzkoff, Dave (March 14, 2016). "Ben Affleck's 'Broken' Batman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

^ McDonald, Soraya Nadia (July 12, 2015). "Paging Hair and Makeup! Ben Affleck Makes his First Public Appearance Since Splitting with Jennifer Garner — at Comic-Con". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Barker, Andrew (March 22, 2016). "Film Review: 'Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice'". Variety. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Truitt, Brian (March 22, 2016). "Review: New Heroes Shine in 'Batman v Superman'". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Berman, Eliza (August 5, 2016). "Does Suicide Squad Really Need That Post-Credits Scene?". Time. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

^ Child, Ben (November 1, 2017). "Five tasks Justice League must complete to save the DC universe". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

^ "Justice League Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

^ McCarthy, Todd (November 14, 2017). "'Justice League': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

^ Lincoln, Kevin (October 16, 2016). "The Accountant Is a Hit, and Ben Affleck Is Truly a Movie Star Again". New York. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

^ Debruge, Peter (October 12, 2016). "Film Review: 'The Accountant'". Variety. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Holden, Stephen (October 13, 2016). "Review: In 'The Accountant,' Ben Affleck Plays a Savant With a Dark Secret". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Lincoln, Ross A. (June 18, 2016). "Warner Bros Pushes 'Lego Movie 2' Release To 2019". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ McClintock, Pamela (January 14, 2017). "Box Office: Why Ben Affleck's 'Live by Night' and Martin Scorsese's 'Silence' Fared So Poorly". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

^ Sims, David (January 13, 2017). "'Live by Night' Is Too Epic for Its Own Good". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017.