Ogilvy (agency)

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP  | |

Type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Advertising, marketing, public relations |

| Founded | 1948 (1948) |

| Founder | David Ogilvy |

| Headquarters | New York City |

Key people | John Seifert, Chief Executive, Worldwide[1] |

| Parent | WPP plc |

| Subsidiaries | Ogilvy Consulting[2] |

| Website | www.ogilvy.com |

Ogilvy is a New York City-based British advertising, marketing and public relations agency. It started as a London advertising agency founded in 1850 by Edmund Mather, which in 1964 became known as Ogilvy & Mather after merging with a New York City agency that was founded in 1948[3] by David Ogilvy. It is part of the WPP Group, which is by revenue one of the largest marketing and communications companies in the world. The agency is known for its work with Dove, American Express, and IBM.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Foundation

1.2 Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather

1.3 Ogilvy, Benson & Mather

1.4 Ogilvy & Mather

1.5 1980s

1.6 1990s

1.7 2000s to present

2 Services

3 Major work

3.1 Early ads

3.2 American Express

3.3 Merrill Lynch

3.4 IBM

3.5 Incredible India

3.6 Dove

3.7 Aspen

4 Controversies

5 See also

6 References

7 Bibliography

8 External links

History

Foundation

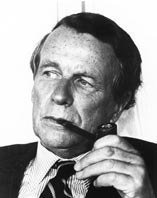

David Ogilvy

The agency was founded in London in 1850 when Edmund Charles Mather began an advertising agency on Fleet Street.[4] After his death in 1886, his son, Harley Lawrence Mather, partnered with Herbert Oakes Crowther and the agency became known as Mather & Crowther.[5] The agency pioneered newspaper advertising, which was in its infancy due to a loosening of tax restrictions and educated manufacturers about the efficacy of advertising and also produced "how-to" manuals for the nascent advertising industry.[5] The company grew in prominence in the 1920s after creating leading non-branded advertising campaigns such as "an apple a day keeps the doctor away" and "Drinka Pinta Milka Day".[5][6]

In 1921, Mather & Crowther hired Francis Ogilvy as a copywriter. Ogilvy eventually became the first non-family member to chair the agency. When the agency launched the Aga cooker, a Swedish cook stove, Francis composed letters in Greek to appeal to British public schools, the appliance's best sales leads. Francis also helped his younger brother, David Ogilvy, secure a position as an Aga salesman.[7] The younger Ogilvy was so successful at selling the cooker, he wrote a sales manual for the company in 1935 called "The Theory and Practice of Selling the Aga Cooker". It was later called "probably the best sales manual ever written" by Fortune magazine.[8]

David Ogilvy sent the manual to Francis who was persuaded to hire him as a trainee. Ogilvy began studying advertising, particularly campaigns from America, which he viewed as the gold standard.[9] In 1938, David Ogilvy convinced Francis to send him to the United States on sabbatical to study American advertising.[10] After a year, Ogilvy presented 32 "basic rules of good advertising" to Mather & Crowther.[11] Over the next ten years, Ogilvy worked in research at the Gallup polling company, worked for British Intelligence during World War II, then spent a few years farming among the Amish community in Pennsylvania.[10]

In 1948, David Ogilvy proposed that Mather & Crowther and another U.K. agency, S.H. Benson, partner to create an American advertising agency in New York City to support British advertising clients. The agencies each invested US$40,000 in the venture but insisted Ogilvy find a more experienced American to run it. David Ogilvy recruited Anderson Hewitt from J. Walter Thompson to serve as president and run sales. Ogilvy would serve as secretary, treasurer, and research director. Along with their British sponsors, which held controlling interest, Hewitt mortgaged his house and invested $14,000 in the agency and Ogilvy invested $6,000.[12][13]

Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather

On September 23, 1948, David Ogilvy opened his United States shop as Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson, & Mather on Madison Avenue in Manhattan.[14] Initially, Mather & Crowther and S.H. Benson gave the agency four clients that were relatively unknown in the United States and had small budgets, including Wedgwood China, British South African Airways, Guinness, and Bovril.[15]

The agency's first account was securing magazine advertising space for Wedgwood.[13] It had its first successful ad with Ogilvy's concept "The Guinness Guide to Oysters", which was followed by several other similar food and Guinness pairing guides.[16] Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson, & Mather's first large client was Sunoco (then called Sun Oil), procured by Hewitt in February 1949.[14]Helena Rubinstein cosmetics was the first client won by Ogilvy.[17]

A breakthrough came after the agency was approached by Maine-based shirt manufacturer C. F. Hathaway Company. The company only had a small budget, but its president promised to "never change a word of copy."[18] In 1951, Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson, & Mather introduced "The man in the Hathaway shirt" campaign. The advertisement featured an aristocratic man in an eyepatch that Ogilvy purchased on the way to the ad's photo shoot. C. F. Hathaway Company sold out of shirts within a week of the first ad's printing. The campaign increased the shirt maker's sales by 160 percent, resulted in new business for Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson, & Mather, and turned the recognizable "Hathaway Man" and his eyepatch into a popular cultural trope.[10][19]

Ogilvy, Benson & Mather

Disagreements between Hewitt and Ogilvy, particularly about creative direction and who should run the agency, resulted in Ogilvy's resignation in 1953.[14]

The agency's backers supported Ogilvy, leading to Hewitt's resignation and the agency reopening as Ogilvy, Benson & Mather in 1954. Ogilvy hired retired Benton & Bowles executive Esty Stowell in 1956 to handle operations and non-creative functions.[20]

During the 1950s, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather became known for its successful campaigns, which David Ogilvy called "Big ideas". The agency, mainly through Ogilvy's creative direction, built a reputation for "quality" advertising, which was defined by its use of well-researched "long copy", large photographs, and clean layouts and typography. Ogilvy believed advertising's purpose was to sell through information and persuasion, as opposed to entertain.[10][21]

That same year, the agency nearly doubled in size after winning the Shell Oil account.[22] The agency agreed to work for Shell on a fee basis, rather than the traditional commission model, and became one of the first major advertising agencies to use the system.[23]

Ogilvy & Mather

As a reaction to the growth of international advertising, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather formed an equal partnership with Mather & Crowther in November 1964.[20] As part of the partnership, the two agencies became subsidiaries of a new parent company called Ogilvy & Mather, which was headquartered in New York. In January 1965, both changed their names to Ogilvy & Mather and the parent company became known as Ogilvy & Mather International inc.[14]

During the 1970s, Ogilvy & Mather acquired numerous other agencies, including S.H. Benson, one of its original sponsors, in 1971, Scali, McCabe, Sloves in 1976, and Cone & Weber in 1977.[14] One of the acquisitions, Hodes-Daniel, resulted in the establishment of the agency's direct response service called Ogilvy & Mather Direct in 1976. It was renamed OgilvyOne Worldwide in 1997.[16] The agency's growth through acquisitions was not led by Ogilvy, who feared the differing philosophies of the acquired agencies would undermine Ogilvy & Mather's culture and advertising beliefs, which he called the "True Church".[24][25] After moving permanently to his French castle Château de Touffou in 1973, David Ogilvy stepped down as chairman and became Worldwide Creative Head in 1975.

1980s

The agency opened its public relations division, Ogilvy & Mather Public Relations, in 1980.[26]

The next year, Ogilvy & Mather established the Interactive Marketing Group and became the first major agency to establish an interactive capability.[27][28] In December 1983, David Ogilvy retired as Creative Head.[29]

In 1985, Ogilvy & Mather International was renamed as The Ogilvy Group inc. The group included three divisions: Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide, a new name for all Ogilvy & Mather offices including Ogilvy & Mather Direct and Ogilvy & Mather Public Relations; Scali McCabe Sloves Group; and several independent associate agencies, such as Cole & Weber. Kenneth Roman, president of Ogilvy & Mather United States, was named president of Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide.[30] He was promoted to chairman of Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide in 1987 and became chairman of Ogilvy Group in 1988, succeeding Phillips.[31]

In 1989, WPP plc, a British advertising holding company, acquired Ogilvy Group for $864 million, which, at the time, was the most ever paid for an advertising agency. David Ogilvy initially resisted the sale, but eventually accepted the title of WPP honorary chairman, a position he relinquished in 1992.[32][33]

Following the departure of Roman for American Express in 1989, Graham Phillips became the chairman and CEO of Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide.[34]

1990s

In 1992, Charlotte Beers replaced Graham Phillips as chairman and CEO of Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide. Philips remained vice chairman. Beers was recruited from agency Tatham, Laird & Kudner and was the first "outsider" to lead the agency.[35] She was also the first woman to lead a major international agency.[36] Beers introduced the concept of "brand stewardship" to the agency, a philosophy of brand-building over time.[37] She is also credited with helping Ogilvy & Mather bring in new business after a downturn.[36]

In 1994, then-North America president Shelly Lazarus and Beers helped win the entire global account of technology corporation IBM for the agency.[37] Worth an estimated $500 million in billings, it was the largest account shift in the history of advertising.[36]

After four years, Beers stepped down as CEO.[36] Lazarus, a 23-year veteran of the agency, was appointed CEO in 1996 and became chairman the next year.[37] It was the first time a woman succeeded another woman at a major agency.[36] Lazarus further developed Beer's brand stewardship approach by introducing "360-degree branding", the idea of communicating a brand message at every touchpoint the brand has with people.[37][38]

David Ogilvy died at age 88 in the Château de Touffou, his home, in July 1999.[10]

2000s to present

Ogilvy purchased The Federalist Group, a Republican lobbying firm, in 2005.[39] The Federalist Group subsequently became bipartisan, changing its name to Ogilvy Government Relations.[40]

In 2005, Shona Seifert and Thomas Early, two former directors of Ogilvy & Mather, were convicted of one count of conspiring to defraud the government and nine counts of filing false claims for Ogilvy over-billing advertising work done for the United States Office of National Drug Control Policy account. The agency was hired by the ONDCP in 1998 to create anti-drug ads aimed at adolescents.[41] At the time, it was

the largest social marketing contract in history.[42] Ogilvy & Mather repaid $1.8 million to the government to settle a civil suit based on the same billing issues.[43][44][45]

Miles Young became Worldwide CEO in January 2009 after leading the company's Asia-Pacific division for 13 years. Lazarus remained chairman until 2012, when Young succeeded her.[46] Under Young's leadership, the agency focused on a "Twin Peaks" strategy of producing advertisements that are equally creative and effective.[47] New business was also Young's priority.[48][49] Young promoted Tham Khai Meng, his creative partner in the Asia-Pacific division, as Worldwide Chief Creative Officer in 2009.[50] Tham laid out a five-year plan to improve the agency's performance at Cannes.[50] According to Adweek, Tham's efforts resulted in the agency being named Cannes Lions "Network of the Year" from 2011 to 2015.[51]

In 2010, the agency established OgilvyRED, a specialty strategic consultancy.[48] In June 2013, OgilvyAction, the agency's activation unit, merged with other WPP-owned properties G2 Worldwide and JWTAction to form Geometry Global, an activation network that operates in 56 markets.[52] Ogilvy's production division, RedWorks Worldwide, merged with production company Hogarth Worldwide forming Hogarth & Ogilvy in March 2015 to serve the production needs of all of WPP's agencies.[53]

The agency was named both the Cannes Lions "Network of the Year" and CLIO "Network of the Year" for four consecutive years, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015.[54][55] It was also named Effies "World's most Effective Agency Network" in 2012, 2013 and 2016.[48][56][57]

Ogilvy Public Relations in China faced accusations in the media of overworking a 24-year-old employee who died of a heart attack while in the office in May 2013. The claims were not confirmed.[58] Four years later a similar event occurred with a young staffer in the Philippines.[59]

In June 2015, Young announced he would retire as both Worldwide Chairman and CEO to take the position of Warden at his alma mater, New College at Oxford University.[46] In January 2016, John Seifert was named CEO of the agency.[60] In November 2017, According to the reports, Ogilvy & Mather won the Turespana account of two million euros.[61]

Similar to other advertising, marketing, and public relations agencies in the years leading up to 2017-2018, Ogilvy has seen an influx of advertisers and publishers establishing in-house "creative" teams, and an industry-wide increase in emphasis in digital media ad buying.[62][63][64] Over the years, the magazine Fast Company wrote, Ogilvy responded to changing demands by creating numerous businesses and "looked more like a holding company of its own".[65] Company leadership said Ogilvy became too complicated.[66] CEO John Seifert launched the company's "re-founding" in June 2018, during which the company changed its name from Ogilvy & Mather to Ogilvy, restructured, and rolled out a new, unified brand and logo to simplify its services.[2] All but one of Ogilvy's sub-brands were wrapped into one: Ogilvy.[2] The company retained its separate strategy division, but renamed it to Ogilvy Consulting.[65][2]

Services

Ogilvy & Mather's services include advertising, public relations, direct marketing, and digital media.[67] Within the company there are a number of units that handle different areas of focus.[68] Ogilvy Public Relations is responsible for the agency's public relations offerings, including branding, public affairs, corporate communication, and digital reputation and influence.[69] OgilvyOne is the agency's direct marketing unit.[68] It also advises clients on customer engagement.[70] The firm's Ogilvy CommonHealth Worldwide unit focuses on healthcare communications and marketing.[71] The agency handles production work through Hogarth & Ogilvy, a joint venture between Ogilvy & Mather and Hogarth Worldwide, formed in 2015.[53] Neo@Ogilvy is a unit of the agency that offers digital media services to all of Ogilvy & Mather's disciplines.[72] As of 2013, sales activation and shopper marketing are administered through Geometry Global, a unit formed through the merger of several WPP agencies, including what was previously known as OgilvyAction.[52]

In addition to agency's main services, Ogilvy & Mather operates several other specialty practices. In 2010,[73] the agency created Ogilvy Noor, a practice focused on creating marketing that appeals to Muslims.[74] OgilvyRED was established in 2011 as a consultancy within the agency that works with Ogilvy's other units to prepare plans for clients' marketing strategies.[75][76] The agency formed Social@Ogilvy in 2012 to work on social media projects for clients. The practice operates within each of Ogilvy & Mather's major units, including advertising, direct marketing, public relations and digital marketing.[67] The behavioural sciences practice #OgilvyChange was also founded in 2012 by Rory Sutherland in Ogilvy & Mather's London office. #OgilvyChange employs psychologists and other behavioural scientists to consult on using research in these fields to understand and influence consumers.[77][78] OgilvyAmp (short for "amplify") handles tasks related to data planning and analytics needs for clients. The unit was established in 2014 and is present at over 50 of the agency's offices.[79] Ogilvy Pride was formed in the agency's London office in 2015 as an LGBT practice.[80]

Major work

Early ads

One of agencies first accounts was Guinness, which tasked it with introducing the beer to an American audience. In 1950, "The Guinness Guide to Oysters" appeared as a magazine advertisement that outlined nine kinds of oysters and their characteristics. The advertisement was successful, and several other pairing guides, including birds and cheeses, followed it.[16][81]

In 1951, "The Man in the Hathaway Shirt", an advertisement created for C. F. Hathaway Company, was first published in The New Yorker. It immediately increased sales for the company and more ads followed. Each featured George Wrangel, a middle-aged man with a moustache and an eye patch. The eye patch was a prop found by David Ogilvy to give the ad what he called "story appeal". Ambassador Lewis Douglas, who wore an eye patch, inspired the concept.[19][82]

To familiarize Americans with Schweppes, the agency created a spokesman named Commander Whitehead. Edward Whitehead, who was the company's president, was introduced as the Commander in a 1952 advertisement, which showed him arriving in New York with a briefcase labeled as the secrets of Schweppes.[83] The campaign resulted in Schweppes becoming the standard tonic used in the country. The campaign continued into the 1960s.[14]

In the 1950s, Ogilvy was hired to increase business in Puerto Rico. The agency created a coupon for businesses that laid out tax advantages of establishing a presence on the island. Approximately 14,000 businesses mailed in the coupon and the territory's foreign industry increased.[84] Following this, David Ogilvy helped Puerto Rico's governor establish and advertise the Casals Festival of Music.[85] The agency created ads using visually captivating images to position the island as a paradise.[86]

In 1952, Ogilvy & Mather launched a campaign to increase tourism for the British Tourist Authority. The "Come to Britain" campaign replaced drawings with photographs of the picturesque countryside. The advertisements resulted in the tripling of tourism to the UK.[16][87]

After the agency was assigned the Rolls Royce account in 1959,[10] David Ogilvy spent three weeks meeting with engineers and researching the car.[88] The resulting advertisement featured the headline "At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls Royce comes from the electric clock", which Ogilvy took (and credited) from a journalist's review.[14] The rest of the copy outlined 11 of the car's distinguishing features and benefits.[20] The advertisement became one of Ogilvy's most famous.[8][10] Ogilvy joked that the ad "sold so many cars we dare not run it again."[88]

American Express

American Express has been an Ogilvy & Mather client since the 1960s.[89] The agency launched the company's "Do You Know Me" campaign in 1974, which focused on the prestige of carrying an American Express card. Each advertisement described the accomplishments of semi-recognizable celebrities who used the card. Their identities were revealed at the end. The campaign emphasized that even if a person was not immediately recognizable, their American Express credit card would be. The campaign ran until 1987.[90][91]

A campaign called "Portraits" followed "Do You Know Me". "Portraits" showed card-carrying personalities like Tip O'Neil and Ella Fitzgerald in leisure activities.[91] The campaign was photographed by Annie Leibovitz and named "Print Campaign of the Decade" by Advertising Age in 1990.[16][92]

Ogilvy & Mather launched the slogan "My Life. My Card." in 2004 with ads featuring celebrities such as Ellen DeGeneres and Tiger Woods.[93] In 2008, American Express won a trademark claim that the company had taken the slogan from a consultant.[94]

In June 2017 American Express shifted almost all the business it had given to Ogilvy to McGarryBowen.[95][96]

Merrill Lynch

Ogilvy & Mather won Merrill Lynch's print and television advertising business in the late 1960s. In 1971, the agency suggested using a bull as a symbol of the company. The visual became the company's logo. The campaign "Bullish on America" debuted in a TV spot during the 1971 World Series, and print ads in 25 magazines followed. Within eight weeks, the perception of Merrill Lynch as the best investment firm among upper-class men went from 19% to 28%.[97]

IBM

Ogilvy & Mather replaced multiple agencies to become IBM's sole agency for all of the company's marketing and branding efforts in 1994. The worldwide campaign "Solutions for a Small Planet" was launched to help rebrand the company.[98]

The agency began creating advertisements under the campaign "Smarter Planet" in 2008. The ads showcased world issues like energy, traffic, food, infrastructure, retail, and banking, and described how IBM was contributing to their improvement.[99] The campaign won a Global Gold Effie in 2010.[100] The second phase of the campaign called "Made with IBM" began in 2014 and showcased work other companies have created using IBM technology.[101]

Incredible India

The agency created the slogan "Incredible India" for the country's Ministry of Tourism in 2002. The campaign targeted an international audience and aimed to boost tourism. The initial advertisements highlighted the breadth of Indian culture and resulted in an increase of two-to-three million tourists per year.[102]

Dove

Dove became an agency client in the 1950s, and developed the brand's "1/4 cleansing cream" messaging.[103] In 2004, the agency launched the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty, a marketing campaign that focused on redefining society's pre-set definitions of "beauty".

The campaign has featured multiple advertisements, workshops, and events. Among the most notable have been a 75-second spot called Evolution and a short film called Sketches.[104] The film earned over 114 million views online and Business Insider noted it as the most viral ad of all time in 2013.[105]

Aspen

In 2014, OCH AP organised a major advertisement campaign for Aspen in Australia.[106]

Controversies

An online video created by Ogilvy & Mather U.K. as viral marketing for the Ford SportKa hatchback spread by email in 2004, despite being rejected by Ford of Europe. The 40-second video, which showed a lifelike computer-generated cat being decapitated by the car's sunroof, led to criticisms from bloggers and animal rights groups. Both companies apologized for its release and launched investigations into how the video was leaked.[107][108]

In 2014, Ogilvy India created "Bounce Back", a campaign for Indian mattress company Kurl-On that illustrated the stories of well-known figures who "bounced back" from adversity. The low point of each narrative arc showed the person rebounding off of a Kurl-On mattress. One of the ads featured Malala Yousafzai and depicted her being shot. The ad was criticized in the media and Ogilvy & Mather issued a public apology to Yousafzai and her family.[109][110]

Also in 2014, Ogilvy & Mather apologized following complaints about the racial implications of an advertisement it created for a South African charity Feed a Child. The advertisement portrayed a black boy being fed like a dog by a white woman.[111]

See also

- David Ogilvy

- WPP plc

References

^ Tadena, Nathalie (20 January 2016). "Ogilvy & Mather Appoints Agency Veteran John Seifert as CEO". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 July 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcd O'Reilly, Lara (5 June 2018). "Ad agency Ogilvy rebrands and restructures to simplify its offering". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

^ "Company Overview of Ogilvy & Mather Inc". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

^ Matt Creamer (April 29, 2013). "Who Was Mather? Meet the Lesser-Known Men Behind Famous Agency Names Granted Immortality Regardless of Contribution". Advertising Age. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ abc Roman 2009, p. 45

^ Winston Fletcher (2008). Powers of Persuasion: The Inside Story of British Advertising 1951-2000. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780191551727. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 48

^ ab Myrna Oliver (July 22, 1999). "David Ogilvy; Legendary Figure of the Ad Industry". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Roman 2009, pp. 56–58

^ abcdefg Constance Hays (July 22, 1999). "David Ogilvy, 88, Father of Soft Sell In Advertising, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 62

^ Roman 2009, p. 84

^ ab Fred Danzig (July 26, 1999). "David Ogilvy: The Last Giant — Creative Titan: Legendary Adman Revered for Humanity". Advertising Age. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ abcdefg "Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide". Advertising Age. September 15, 1999. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 85

^ abcde Ninart Lui (January 5, 2009). "Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide 60th Anniversary". DesignTAXI. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 87

^ Roman 2009, p. 89

^ ab Roman 2009, p. 90

^ abc John McDonough (September 21, 1998). "Ogilvy & Mather at 50 - The 'House that David built' still lives by his precepts: 3 of 4". Advertising Age. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 125

^ Roman 2009, p. 134

^ "Fee System". adage.com. Advertising Age. September 15, 2003. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

^ Roman 2009, pp. 146,164

^ Michael Wolff (June 13, 2011). "The First (and Last) Adman". AdWeek. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Philip H. Dougherty (September 20, 1983). "Ogilvy & Mather Forms Public Relations Unit". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ "Talk to The Times: Martin A. Nisenholtz". The New York Times. March 8, 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

^ "Plugging into Interactive Early on Ogilvy & Mather Martin Nisenholtz". Advertising Age. September 12, 1994. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

^ Jeffrey Sonnenfeld (1988). The Hero's Farewell: What Happens When CEOs Retire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199839162. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

^ Philip H. Dougherty (January 28, 1985). "Advertising;Changes Planned At Ogilvy". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Julia Flynn Siler (February 8, 1988). "Advertising; An Orderly Succession At Ogilvy". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Randall Rothenberg (May 16, 1989). "WPP's Bid Is Accepted By Ogilvy". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 190

^ Roman 2009, p. 192

^ Roman 2009, p. 218

^ abcde Stuart Elliott (September 9, 1996). "From One Woman to Another, Ogilvy & Mather Is Making History". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ abcd "Lazarus, Rochelle "Shelly"". Advertising Age. September 15, 2003. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Robert Reiss (March 1, 2010). "How Philanthropy Builds A Brand". Forbes. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Mark Hand and Ravi Chandiramani (September 23, 2005). "Ogilvy buys public affairs group". PR Week.

^ Catherine Ho (May 19, 2013). "Ogilvy Government Relations eyes a comeback". The Washington Post.

^ Stuart Elliott (February 23, 2005). "Billing Convictions Set Off Shudders on Madison Ave". The New York Times.

^ Nora Fitzgerald (November 3, 1997). "Media Agencies: A Social Contract". AdWeek. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Matthew Creamer (July 14, 2005). "SHONA SEIFERT SENTENCED TO 18 MONTHS IN PRISON". Advertising Age.

^ Matthew Creamer (July 13, 2005). "THOMAS EARLY SENTENCED TO 14 MONTHS IN PRISON". Advertising Age.

^ James Hamilton (February 25, 2005). "Ad executives lose fraud case". Campaign.

^ ab Jesse Oxfeld and Andrew McMains (June 17, 2015). "Ogilvy CEO Miles Young to Step Down, Become Oxford Administrator Global chief returns to his alma mater". AdWeek. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ "Five Pre-Cannes Questions With Ogilvy CCO Tham Khai Meng". Advertising Age. March 22, 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ abc Noreen O'Leary (March 3, 2013). "Ogilvy Chief Miles Young Is Busy Reinventing a Troubled Agency". AdWeek. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Daniel Farey-Jones (April 14, 2010). "InterContinental hands Ogilvy global customer marketing business". Campaign. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ ab "Interview / Tham Khai Meng". Contagious. July 5, 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

^ Noreen O'leary (July 2, 2015). "With CEO Miles Young Leaving Ogilvy, Will His Loyalists Follow Him Out?". AdWeek. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

^ ab Simon Nias (June 21, 2013). "WPP merges G2, OgilvyAction and JWTAction to form Geometry Global". Campaign. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ ab Elizabeth Low (April 14, 2015). "WPP creates global production unit, merging Ogilvy's RedWorks with Hogarth". Marketing. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Noreen O'Leary (June 30, 2015). "Inside Grey's Global Sweep of 113 Lions at Cannes 18 offices won, nearly double the amount in 2014". AdWeek. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Anisha Kapoor (October 2, 2015). "Ogilvy & Mather Wins Network of the Year at 2015 CLIO Awards". World Branding Forum. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

^ "2013 Effie Effectiveness Index" (Press release). Effie Worldwide. June 20, 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

^ Kapoor, Anisha (2016-04-29). "Ogilvy & Mather Reclaims World's Most Effective Effie Title". World Branding Forum. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

^ Anita Chang Beattie (May 16, 2013). "Overworked? 24-Year-Old Ogilvy China Staffer Dies After Heart Attack at Desk". Advertising Age. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

^ Coffee, Patrick (February 23, 2017). "Death of an Ogilvy Philippines Employee Sparks Renewed Debate Over Work-Life Balance at Agencies". AdWeek.

^ Noreen O'Leary (January 20, 2016). "Ogilvy Has Named a New Global CEO". Adweek. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

^ "Ogilvy & Mather gana la cuenta de Turespaña de dos millones de euros". Dircomfidencial (in Spanish). 2017-11-03. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

^ Oster, Erik (17 April 2018). "Will Martin Sorrell Be Remembered for Saving the Ad Industry, or for Crushing Its Soul?". Adweek. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

^ Oster, Erik (9 April 2018). "Why In-house Publishers Are Becoming Attractive Alternatives for Advertisers and Creatives". Adweek. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

^ Kirkpatrick, David (3 April 2017). "What Ogilvy's 'refounding' says about the state of agency-brand relationships". Marketing Dive. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

^ ab Beer, Jeff (5 June 2018). "Ad giant Ogilvy unveils global company rebrand and reorganization". Fast Company. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

^ Coffee, Patrick (5 June 2018). "Ogilvy Rebrands Itself After 70 Years With New Visual Identity, Logo and Organizational Design". Adweek. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

^ ab Stuart Elliot (13 February 2012). "Ogilvy & Mather Staffs Up in Social Media and Youth Marketing". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ ab Brigid Sweeney (1 December 2012). "Ogilvy Chicago changes its business model along with its location". chicagobusiness.com. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ "Ogilvy Public Relations". J. R. O'Dwyer Company. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Elyse Dupre (November 20, 2012). "Customer Engagement: the sum of all parts". Direct Marketing News. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Larry Dobrow (July 1, 2015). "Top 100 Agencies: Ogilvy CommonHealth Worldwide". Medical Marketing and Media. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Jon Gingerich (February 3, 2016). "Rittenhouse Reps Neo@Ogilvy in Tokyo". J. R. O'Dwyer Company. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Shelina Janmohamed (January 28, 2016). "I'm Muslim, female, wear a headscarf – and, believe it or not, I work in advertising". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Monica Sarkar (October 5, 2015). "H&M's latest look: Hijab-wearing Muslim model stirs debate". CNN. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Noreen O'Leary (December 3, 2012). "Agencies Make Strategic Play More shops are eyeing business usually handled by management consultants". AdWeek. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ "Ogilvy & Mather bullish on opportunities". The Nation. January 30, 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ "The Maddest Men of All Full Transcript". Freakonomics. 26 February 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

^ Rezwana Manjur (July 18, 2014). "O&M brings behavioural sciences arm to Asia". Marketing. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ Stuart Elliott (October 20, 2014). "At Ogilvy, New Unit Will Mine Data". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

^ David Gianatasio (September 15, 2015). "As More Marketers 'Go Rainbow,' Is a Boom in LGBT Specialty Shops on the Horizon?". Adweek. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

^ Roman 2009, p. 86

^ Emma Bazilian (September 21, 2011). "Calling Mr. Hathaway Saks and Fairchild's 'Footwear News' revive David Ogilvy's eye patch icon". Adweek. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 92

^ Roman 2009, p. 94

^ Roman 2009, p. 95

^ Stuart Elliott (December 3, 2009). "Puerto Rico Revives a 50-Year-Old Campaign". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 136

^ ab Roman 2009, p. 99

^ Roman 2009, p. 137

^ Allen P. Adamson (2007). BrandSimple: How the Best Brands Keep it Simple and Succeed. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9781403984906. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ ab Leslie Savan (2010). The Sponsored Life: Ads, TV, and American Culture. Temple University Press. pp. 141–142.

^ Ann M Mack (March 15, 2002). "American Express Kicks Off New Corporate Campaign". Adweek. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Eric Dash (July 28, 2005). "American Express Sued Over Advertising Tagline". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Ryan Davis (February 5, 2008). "AmEx Prevails In "My Life. My Card." Trademark Suit". Law360. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Coffee, Patrick (June 9, 2017). "American Express Moves Its Global Brand Account to Mcgarrybowen After More Than 50 Years With Ogilvy".

^ Coffee, Patrick (May 21, 2018). "American Express to Review Its Global Media Business After 20 Years With WPP". AdWeek.

^ Winthrop H. Smith, Jr (2014). Catching Lightning in a Bottle. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118967614. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Allen P. Adamson (2007). BrandSimple: How the Best Brands Keep it Simple and Succeed. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 56–58. ISBN 9781403984906. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Joel Makower (January 3, 2009). "Behind IBM's Quest for a 'Smarter Planet'". GreenBiz. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Jon Miller, Lucy Parker (2015). Everybody's Business: The unlikely story of how Big business can fix the world. Jaico Publishing House. ISBN 9788184956443. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Seth Fineberg (April 11, 2014). "IBM Launches Updated Smarter Planet Effort During Masters". Advertising Age. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ "'Incredible India' campaign has run its course: Experts". Deccan Herald. October 22, 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Roman 2009, p. 98

^ "Top Ad Campaigns of the 21st Century". Advertising Age. 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Laura Stampler (May 22, 2013). "How Dove's 'Real Beauty Sketches' Became The Most Viral Video Ad Of All Time". Business Insider. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ http://www.coloribus.com/adsarchive/prints-outdoor/gastro-stop-bus-19880755/

^ Elizabeth Day (April 4, 2004). "Decapitated cat video backfires on Ford". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Mark Morford (May 5, 2004). "Very Funny Cat Decapitations / Is it OK to laugh when small European cars maim cute fuzzy animals? A perspective check". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Jeff Beer (May 13, 2014). "The least creative thing of the day: this ad uses Malala Yousafzai to sell mattresses". Fast Company. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ Rebecca Cullers (May 16, 2014). "Ogilvy Apologizes for Shooting Malala Yousafzai in Mattress Ad Work from India is shockingly crass". Adweek. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

^ "Ad showing black boy being fed like dog faces no action — CNN.com". CNN. 2014-07-11. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

Bibliography

Roman, Kenneth (2009). The King of Madison Avenue: David Ogilvy and the Making of Modern Advertising. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 45–218. ISBN 9781403978950. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

External links

- Official website