恋童

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | 恋童 | |

|---|---|

| 同義詞 | 恋童癖、恋童障礙 |

| |

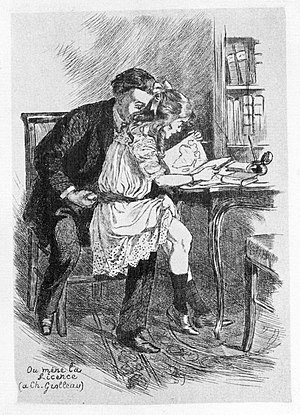

一幅描述成人过度喜爱未成年的女童的漫画。 | |

| 醫學專科 | 精神科 |

| 症状 | 認為青春期前的兒童擁有主要的性吸引力[1][2] |

| 常見始發於 | 青春期前或期間[3] |

| 病程 | 持續終生[3] |

| 肇因 | 成因不明[4] |

| 治療 | 無法治癒,但有治療方法能減低其性侵犯兒童的機會[5] |

| 盛行率 | 盛行率不明,但估計佔總成年男性人口的<5%[6] |

恋童是一種精神障礙,16歲以上的青少年或者成年人患者會認為青春期前的兒童擁有主要的性吸引力,或只有兒童才有性吸引力[1][2]。雖然在10-12歲(女孩:10-11歲;男孩:11歲-12歲)之間兒童會開始踏入青春期[7],但戀童的標準延長至13歲[1]。被診斷患有戀童癖的人必须至少年滿16歲,且比其認為擁有性吸引力的兒童大5歲[1][2]。

恋童在《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》第5版当中正式命名为恋童障礙(pedophilic disorder)。並將其定義為對青春期前的兒童擁有強烈且反復的性衝動和幻想,且已就這種性衝動採取行動或受其困擾(比如人際關係受阻)的人[1]。尚未生效的《國際疾病分類第11版》則將其定義「持續而又專一的強烈性興奮——表現為持續出現針對青春期前的兒童的性思想、性幻想、性衝動以及性行為」[8]。

恋童這個字詞常被大眾用於表示對兒童的任何性興趣或兒童性侵犯[9][5],但這種用法卻把「對兒童的性衝動」(思想)和「兒童性侵犯」(行為)混為一談,且没有區分處於青春期前、青春期,和青春期後的未成年人[10][11]。研究者建議避免在這種情況下使用「恋童」這個不精確的字詞,儘管性侵兒童者有可能患上這種疾病[5][12]。性侵兒童者並不等同恋童者,除非當事者認為青春期前的兒童具有主要的性吸引力,或只有兒童才有性吸引力[10][13][14]。現有文獻指出有些恋童者並不性侵犯兒童[9][15][6]。

戀童於19世紀末首次被正式認定和命名。自20世纪80年代以來,研究者已針對戀童進行了大量的研究。虽然大量有關戀童的記錄都聚焦於男性,但也有女性擁有戀童的傾向[16][17]。研究者認为現有估計不能完全呈现女性戀童者的真實數量[18]。目前沒療法能治癒戀童,但是有一些治療方法可以減少恋童者性侵犯兒童的機會[5]。戀童癖的確切成因不明[4],但一些關於性侵兒童的戀童罪犯研究則顯示其與各種神經系統異常和精神病理有關[19]。美國在經歷堪薩斯訴亨德里克斯一案後,被診斷患有某些精神障礙的性犯罪者可遭到無限期的預防性拘留,特別是戀童癖[20]。

目录

1 定義及詞源

2 體徵和症狀

2.1 發展和性傾向爭議

2.2 共病和人格特質

2.3 兒童色情作品

3 病因

4 診斷

4.1 DSM、ICD-10及ICD-11

4.2 对診斷标準的質疑

5 治療

5.1 认知行为治療

5.2 行為介入治療

5.3 性欲降低治療

6 流行病學

6.1 恋童與性侵犯兒童

7 歷史

8 法律與法庭心理學

8.1 定義

8.2 預防性拘留

9 恋童與社會

9.1 誤用用詞

9.2 戀童擁護團體

9.3 反戀童行動

10 参见

11 參考文獻

12 外部链接

13 延伸閲讀

定義及詞源

「pedophilia」一詞來自希臘語:「παῖς,παιδός」(paîs, paidós,兒童)以及「φιλία」(philía,友愛)[21]。恋童是用於形容某人認為13歲或以下的兒童擁有主要的性吸引力,或只有其才有性吸引力的想法[1][2]。戀幼(Infantophilia或Nepiophilia,但後者少見於學術文獻[22][23])是恋童的一个子类型,用於形容某人認為5歲或以下的兒童擁有主要的性吸引力[24][12]。「Nepiophilia」一詞同源於希臘語:νήπιος(népios,嬰兒或小孩)[22][23]。戀少年則用於形容某人認為11-14歲的少年擁有主要的性吸引力,或只有其才有性吸引力的想法[25]。DSM-5並没有把戀少年列入診斷名單上,而現有證據表明,戀少年與戀童是應分開看待的,但ICD-10的戀童定義與戀少年的重疊[6]。除了戀少年外,一些臨床医師还提出了與戀童有些相似或完全不同的分類名稱,例如廣義戀童癖(Pedohebephilia,包含戀童癖和戀幼癖)與戀青少年(Ephebophilia)[26][27]。

體徵和症狀

發展和性傾向爭議

戀童傾向會在青春期前或期間出現,且伴隨終生[3]。患者会自行發現不受自己選擇或控制的戀童傾向[5]。基於上述特質,有一些意見會把其視為一種性倾向,與異性戀或同性戀相似[3]。然而這些觀察結果並不能使戀童癖從眾多精神疾病中脫離,因為與戀童相關的行為會對他人構成傷害,且他們在精神衛生專業人員的幫助下能避免採取任何傷害兒童的行為[28]。

原本的DSM-5把戀童定為一種性倾向,並區分了性偏離和戀童障礙、戀童和戀童障礙。美國精神醫學學會為了回應因DSM-5的措辭而產生的誤解,特地指出:「『性取向』此用語並不能用於戀童障礙的診斷標準。DSM-5的這種用法是錯誤的,應該把其改成『性興趣』……事實上本學會認為戀童障礙是『性偏離』的一種,而不認定其為一種『性取向』。此錯誤將在電子版的DSM-5和《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》的下一印刷版本中糾正。」他們表示強烈支持起訴那些虐待剝削兒童或青少年的人,並「支持繼續發展針對戀童障礙的治療」[29]。

共病和人格特質

有關戀童性罪犯的研究往往顯示他們還存有其他的精神病理,比如低自尊[30]、抑鬱、焦慮以及其他性格問題。但目前尚不清楚這些精神病理是哪種因素導致:疾病本身所带來的問題、抽樣偏倚、被裁定為性罪犯都有可能有所影響,且它們在这(些)研究中無從分離[19]。一項文獻綜述亦得出结論,認為戀童者的個性與精神病理研究所使用的研究方法鮮少是正確的,部分可歸因於它們混淆了戀童者和兒童性罪犯,以及難以取得具代表性的戀童者社區樣本[31]。塞托(Seto)於2004年指出從臨床環境中取得的戀童者樣本很可能因為他們的性興趣以及社会压力而感到困擾,繼使他們出現心理問題的可能性增加。從懲教所中抽取的戀童者樣本亦同樣如是,他們可能因为被判有罪的关系而出現反社會人格特徵[32]。

一些符合科恩(Cohen,2004)等人所制定的戀童診斷標準的兒童性侵犯罪犯樣本報稱自我概念(Self-concept)和人际功能受損。研究者們認為這可能是戀童者性侵兒童的促成因子。與健康的对照组相比,研究中的戀童性犯罪者樣本有較高机会患上其他类型的精神病,以及出現認知扭曲。研究者解釋道这是他們不能抑制自己不去犯罪的原因[33]。兩項分别發表於2009年和2012年的研究發現,非戀童的兒童性侵犯者很多都患有精神病,而戀童者則没出現这种現象[34][35] 。

威爾遜(Wilson)和考克斯(Cox)於1983年时發表了一項研究,其研究了一群戀童俱樂部成員的人格特質。戀童组和控制组之間最顯著的差異在於他們的內向程度,戀童组的害羞和抑鬱程度都較高,且較容易流於感性。戀童组在神經質和精神病性方面得分較高,但不足以認定為病態。該研究的負責人警告說:「我們难以区分戀童的成因和影響。我們不知道戀童者是否因為高度內向而偏愛於低威脅性的兒童,抑或是偏愛兒童的缘故,使他們的內向性增加——即他們意識到戀童所引起的社會不滿和敵意(P,324)[36]。」在一項非臨床調查中,46%的戀童者报稱曾因自身的性興趣而認真地考慮過自殺,已有計劃自杀的亦有32%,曾試图自杀的則有13%[37]。

一項綜述回顧了1982年至2001年間發表的研究並得出结論,指出兒童性侵犯者会利用認知扭曲去滿足個人需要:以藉口作理由去為性侵犯行為合理化、重新界定自己的行為為互利且由愛所驱使的,並会利用兒童-成年人關係中的權力不對等去行事[38]。常見於兒童性侵犯者的認知扭曲還包括「兒童為性化的存在」、性行為是無法控制的,以及「性權利偏見」(即認为自身擁有這種權利)[39]。

兒童色情作品

觀看兒童色情作品是一種比性侵犯兒童更可靠的戀童指標[40],儘管一些非戀童者也曾觀看兒童色情作品[41]。兒童色情作品可用於各種目的,包括滿足性欲、與其他收藏家交易,以至給其他遭性誘拐的兒童觀看,培養性奴隸[42][43][44]。

觀看兒童色情作品的戀童者往往會執著地收集、組織,和分類它們,並按年齡、性別、性行為的種類把它們逐一標籤[45]。美國聯邦調查局局長肯·蘭寧(Ken Lanning)指出,「收集」兒童色情作品的意思並不代表他們只会觀看之,還代表他們會貯存兒童色情作品,並用以「定义、激起,和驗證他們最珍貴的性幻想[41]。」蘭寧同時說明道罪犯的收藏是他們想幹什麼的最佳唯一指標,但那些收藏並不代表他們曾做过的行為[46]。研究者泰勒(Taylor)和奎爾(Quayle)寫道戀童的兒童色情作品收藏家會為了擴展他們的收藏,而經常參與匿名的互聯網社區[47]。

病因

儘管目前恋童的成因不明,但研究者自2002年开始發現一系列的大腦結構和功能異常與戀童相關。他們從刑事司法系統內外的各種渠道招募個体來測試,並設立控制組。相关研究已發現恋童與較低的智商[48][49][50]、記憶測試得分較低[49]、非右撇子[48][49][51][52]、去除智商因素影響的学業失敗[53]、較輕的體重[54][55]、儿童时期头部受伤[56][57],以及幾個利用核磁共振成像所檢測到的腦結構異常[58][59][60]有關。他們的研究結果表明某些先天的神經學特徵會使擁有者患上恋童的機會增加,甚至導致其恋童。一些研究發現戀童者發生認知受損的機會較非恋童的兒童性侵犯者低[61]。一項發表於2011年的研究則指出恋童的兒童性侵犯者在反應抑制方面有缺陷,但沒有記憶或認知彈性方面的缺陷[62]。有關恋童的可遗传性的研究表明「目前的證據傾向於戀童受到遗传因子影響,但仍不能證明其確實關係[63]。」2015年的一項研究表明,戀童的性犯罪者擁有正常的智商[64]。

一項使用核磁共振成像(MRI)去協助進行的研究則顯示男性恋童者的腦白質容量低於控制組[58]。另一項利用功能性磁共振成像去測量神經元活動的研究亦顯示,遭診斷為恋童的兒童性侵犯者在觀看成人主演的色情照片時,其下丘脑活躍程度較非恋童者低[65]。2008年的一項神经成像研究則指出,異性戀「戀童住院患者」的性刺激處理中心因前額葉網絡異常而有所改變,其「跟像強迫性性行為般的刺激控制行為(stimulus-controlled behaviours)可能存有關聯。」他們的研究發現也可能表明「性興奮處理過程中的認知障礙可能與戀童有關[66]。」

布蘭查德(Blanchard)、坎托(Cantor)以及羅比肖(Robichaud)於2006年發表了一篇综述,其檢視了多篇關於戀童者激素水平的研究,並得出结論:儘管有一些證據表明男性恋童者的睾酮水平低於控制組,但相关研究的質量較差,而且很難從中得出任何结論[67]。

童年时遭受成年人虐待及患有像人格障礙般的精神疾病是戀童者為他們的慾望採取行動的風險因子[5]。布蘭查德等人為此指出:「此理论背后的意義尚不明確——是否特定的基因或產前環境中的有害因子會使男性同時患上情感障礙和戀童癖?还是因自身不受眾人接受的性慾而感到沮喪孤獨?抑或是因偶尔私下的性滿足而感到焦慮和絕望?」他們表示因為戀童者的母親更有可能接受精神治療,所以「特定的基因使男性同時患上情感障礙和戀童癖」是最有可能的答案[56]。

一項運用威爾遜性幻想調查表去分析200名異性恋男性的研究則顯示,更有可能出現性偏離現象(包括恋童)的男性擁有較多的兄長、食指和無名指的指長比較高(這表明產前接觸雄激素的机会較少)、較大機會是左撇子。其亦指出腦功能侧化可能在性偏離上扮演着一定角色[68]。

診斷

DSM、ICD-10及ICD-11

《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》第5版比以前的DSM-IV-TR顯著擴大了戀童的診斷部分,其指出:「戀童障礙的診斷標準同時適用於願意或不願意透露自己擁有這種性偏离的人,只要存有客觀證據[1]。」正如DSM-IV-TR,手冊的第5版概述了用於診斷這種疾病的具體標準,包括「在至少6个月的时间内,频繁而强烈地激起性的兴趣,如性幻想、性欲望或性行为,对象为青春期前的儿童(一般年龄在13岁或以下)」、「 个人针对这些欲望采取了行动,或性欲、性幻想引发了显而易见的痛苦或者人际困难」以及「个人年龄至少16岁,并且比首条中的儿童至少大5岁。」其還可根據「該人所偏愛的对象的性別」、「只對近親儿童擁有衝動或行為」、「是否只偏愛儿童」來作細緻診斷[1]。

ICD-10則定義恋童为「对处於青春期前或青春期前期的兒童的性偏愛,不論所偏愛的兒童是男还是女[69]。」正如DSM一樣,这个診斷系統所診斷的人士必需年滿16岁,且持續地認為比自己至少小5岁的兒童擁有最主要的性吸引力,或只有其才有性吸引力[2]。尚未生效的ICD-11把恋童障礙定義為「持續而又專一的強烈性興奮——表現為持續出現針對青春期前的兒童的性思想、性幻想、性衝動以及性行為」[8]。它同時指出若要對恋童障礙作出診斷,「受診者必需就着这些思想、幻想、衝動采取了行动,或这些念頭引发了显而易见的痛苦。此一診斷並不適用於跟年紀相近的人一起從事性行為,且處於青春期前或青春期後的儿童」[8]。

為了使「真正的恋童罪犯」跟非恋童或非只恋童的罪犯區分,研究者已使用了好幾个帶差異的用語,並依據恋童的程度、是否只偏愛儿童以及犯罪動機去把犯罪者分門別類。只偏愛儿童的恋童者有時會被稱為「真正的恋童者」。他們只認為只有青春期前的儿童才有性吸引力,並對成年人沒有性方面的興趣。他們只能在幻想青春期前的儿童或其在埸時得到性興奮[18]。雖然「非只偏愛儿童的性罪犯」(non-exclusive pedophiles)有時會用於表示「非恋童的性罪犯」,但上述兩者的意思並不相同。「非只偏愛儿童的恋童者」認為儿童还是成人都有性吸引力,並能对以上兩者展現性興奮,儘管仍有例子是偏向其中一者的。如果某人偏向認為儿童的性吸引力大於他者,那就會遭認定為「恋童的性罪犯」[69][18]。

不論DSM還是ICD-10,都不會只依據「和青春期前的儿童實際發生性關係與否」來作診斷。相反診斷者亦可依據受診者的幻想或性慾作出診斷。另一方面没有对其欲望感到困擾的但有相關行為的人亦可符合診斷標準。「行动」的定義也不只限於實際的性行為,有時還包括露體、偷窺、性摩擦行為,以及对着兒童色情作品自慰[1][40]。診斷者在臨床診斷時需判斷這些行為的背後意義;當受診者處於青春期後期時亦同樣需考慮「年齡差異」這一要點[70]。

对診斷标準的質疑

已有批評認為DSM-IV-TR的診斷标準範圍在一些方面過於寛鬆,在另一些方面則過窄[71] 。雖然大多數研究人員會對兒童性侵犯者和戀童者進行區分[13][14][6][71],但DSM的診斷标準被斯圖德(Studer)和艾爾文(Aylwin)批評過於寛鬆,使得所有兒童性侵犯者都能遭診斷成戀童癖。兒童性侵犯者符合條件1和條件2的要求,因為他們跟青春期前的儿童發生性行为,且采取了行动[71]。他們及後亦批評了标準範圍過份狹窄,使得没采取过行动及不对其感到困擾的人无从診斷[71]。他們兩人以外的好幾位研究者亦曾針对后一点發表过批評,他們認為一位只對兒童進行性幻想並自慰的人不應只因不符合条件2而不受診断[6][72][73][74]。一項大規模調查表明,診斷者很少使用DSM的相關分類及診斷标準。調查者解釋道這是因為它的相關标準欠缺有效性、可靠性、清晰度,以及标準過鬆[15]。

因研究戀童而聞名的性學家雷·布蘭查德針對上述對DSM-IV-TR的反對意見,提出了適用於所有性偏離的解決方案。並以此區分了性偏離和性偏離障礙。若受診者符合標準1和2,則可診斷成患有性偏離障礙;若只符合標準1,則只可確定其擁有性偏離現象[75]。布蘭查德和另外幾位研究者同時建議把戀少年纳入DSM-5中,成为可診斷的精神障礙,並跟恋童障礙結合,解決戀童和戀少年之間的年龄重疊,但認為應區分受診者所偏愛的年齡範圍.[26][76]。美國精神醫學學會拒絕了他們針對戀少年的建議[77],但卻接纳了性偏離障礙和性偏離的區分[1][78]。

美國精神醫學學會指出:「就恋童障礙的情況而言,新的診斷手冊沒有顯著修改其任何細節。儘管在DSM-5的编寫過程中我們探討了各種建議,但診斷標準最終跟DSM-IV TR的保持一致……唯一的改變就是把恋童改為恋童障礙此一名稱,為的是與章節的其他疾病名稱保持一致[78]。」如果戀少年在DSM-5中成为可診斷的精神障礙,那麼它的定義將類似於ICD-10为戀童所下的般,包括對處於早青春期的少年的偏愛[6],並使確診者所需的年齡從16歲升至18岁(且需比未成年人至少大5歲)[26]。

奥多诺休(O'Donohue)建議把DSM的診斷標準簡化成只需確定「認為兒童擁有性吸引力」就行,因为其可经由實驗、自我報稱以及過去的行為判定。他指出任何認為兒童擁有性吸引力的想法都是病態的,受其困擾與否根本無關緊要,並指出「這種想法有可能對他人構成極大損害,也不符合個人的最大利益[79] 。」霍華德·巴爾貝(Howard E. Barbaree)和邁克爾·塞圖(Michael C. Seto)於1997年表示不同意美國精神醫學學會就戀童所下的行為標準定義,並建議以行動作為診斷戀童的唯一標準,簡化分類[80]。

治療

目前無證據證明恋童是能夠治癒的[6]。現時大多數的治療方案都聚焦於幫助恋童者避免就他們的欲望採取任何行動[5][81]。儘管一些治療方法宣稱能夠治癒恋童,但迄今仍没研究證明其能長期地改變一個人的性偏好[82]。性學家邁克爾·塞托指出,任何嘗試治愈成年人戀童的療法都不太可能成功,因為它的發展受到產前因素影響[6]。約翰·霍普金斯性障礙診所的創始人弗雷德·柏林認為,戀童是繼同性戀或異性戀之后最難改變的性偏好[83],但是可幫助恋童者控制自己的行為,並於將來發展一套預防方法[84]。

恋童治療效果的研究局限於幾個常見的因素。首先大多數研究只以行為來區分樣本,而不考慮对象的年齡偏好,使得具體的治療效果很難從中反映出來.[5]。其次大多研究不隨机分配治疗组和控制组的研究樣本。研究者會因為拒絕或退出治療的罪犯的犯罪風險較高,而把他們從已治疗组排除,但不排除已拒絕研究或退出對照組的对象,使得已治療組受到偏袒,並令结果不可信[6][85] 。目前没有研究能證明相關治療套用於没犯过罪的恋童者后會產生怎樣的效果[6]。

认知行为治療

认知行为疗法旨在使接受治療的性犯罪者出現不利于兒童的態度、信念和行為的可能性降低。其內容因治疗師而異,但典型的治疗方案一般會嘗試提升接受治療者的自我控制能力、社會能力和同情心,並以認知重構此一过程去改變接受治療者对跟兒童發生性行為的看法。這疗法最常见的形式就是再犯預防,其旨在根據用於治療成癮症的原則,教導患者來識別和應對潛在的危險情況[86]。

认知行为治療的有效性證據不一[86]。一項發表於2012年的文獻回顧回顾了以往的隨機實驗,發現认知行为治療不能減低性犯罪者重犯的机会[87]。兩項分别發表於2002年和2005年的元分析納入了各种隨机和非隨机试验,並得出结論,認為认知行为治療可以減少再犯机会[88][89]。非隨機研究的翔實性存有爭議[6][90]。亦需待更多的研究來評估认知行为治療的效用[87]。

行為介入治療

行为治疗的目的在於壓制对兒童的性興奮。其以「饜足和嫌惡」技巧來壓制對兒童的性興奮,並以隱性敏感法(自慰再制約法)去增加对成人的性興奮[91]。行為治療對陰莖膨脹測試間的性興奮模式有所影響。但是不知道这代表的是什麼:不論性興趣的改變,還是測試過程中控制生殖器興奮能力的變化都有可能導致這種效果。而其長期效果亦仍待研究[92][93]。應用行為分析則在患有精神障礙的性犯罪者当中有所應用[94]。

性欲降低治療

藥物介入措施一般用於降低恋童者的性欲,從而減輕其对兒童的性興趣,但这並不能使恋童者不再恋童[95]。抗雄激素通過干擾睾酮的活性而起作用。而醋酸环丙孕酮和醋酸甲羟孕酮是最常應用於相關治療的抗雄激素。儘管現有一定證據支持抗雄激素的療效,但高質量研究仍然欠奉。現时已有有力的證據支持醋酸环丙孕酮對降低性欲的效果,醋酸甲羟孕酮的療效證據則不一致[96]。

像亮丙瑞林般的促性腺素激素类似物亦同樣可以降低性欲,但其作用时間較長,副作用亦較少[97],效果如同选择性5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂(SSRIs)[96]。這些替代藥物的療效證據更為有限,且相關證據多基於非盲實驗和案例研究[6]。上述治療一般統稱作化学阉割。化学阉割常與認知行為治療一同併用[98]。性犯罪者治療學會指出,治療兒童性侵犯者時,「抗雄激素治療應配合適當的監測和綜合治療輔導[99]。」這些藥物具有的可能副作用包括體重增加、乳房發育、肝臟損害,以及骨質疏鬆[6]。

手術閹割在歷史上曾用於使戀童者的睾酮水平降低,繼而達至減少性慾的目的。但當降低睾酮水平的藥理學方法出現時,其已在很大程度上顯得过时。因為化学阉割具有跟手術閹割同樣的效果,且侵害性較小[95]。但它仍偶爾出現於德國、捷克共和國、瑞士,以及美國的好幾个州份。非隨機抽样的研究指出其能減少性罪犯再犯的機會[100]。性犯罪者治療學會对手術閹割持反对態度[99],而欧洲委员会則致力於禁止部分仍在實行手術閹割的東歐國家繼續進行之[101]。

流行病學

恋童與性侵犯兒童

恋童的人口盛行率不明[6][32],但估計佔總成年男性人口的低於5%[6]。女性戀童者的盛行率知之甚少。但是仍有女性強烈認為青春期前的兒童擁有性吸引力,並产生性衝動的病例[16]。大部分兒童性侵犯者為男性。據估計被定罪的性罪犯當中女性可能佔0.4%至4%。一項研究估計,兒童性侵犯者的男女比例為10比1[18]。現有的估計可能並不能反映女性兒童性侵犯者的真實數量,部分原因在於「社會傾向忽略年輕男子和成年女性之間發生性關係的負面影響,以及女性更容易接觸无法/不懂向他人求援的年幼兒童[18]。」

恋童此一用詞经常用於表示所有兒童性侵犯者[10][14],但此一用法遭到研究者們反對,因为許多兒童性侵犯者並沒有對青春期前的兒童展現強烈的性欲,所以許多都不能算作戀童[13][14][6][71]。有許多性侵犯兒童的動機與戀童無關[80],例如壓力过大、婚姻問題、没有成年性伴侣[102]、反社會傾向、性欲过高,以及飲用酒精飲料[103]。由於性侵犯兒童不能成為犯罪者擁有恋童傾向的指標,所以其能分成兩种不同类型的兒童性侵犯犯罪者:戀童和非戀童[104](或分為情境性和原發性[11])。兒童性侵犯者的戀童率估計一般在25%至50%之間[105]。一項發表於2006年的研究則發現35%的兒童性侵犯者樣本为恋童的[106]。近亲性交罪犯當中少見戀童者[107],特别是父親或繼父為戀童者的情況[108]。美國的一項研究調查了2429名都被歸类为戀童的成年男性性犯罪者,並發現当中只有7%是只偏愛兒童的戀童者,其餘的都是非只偏愛兒童的兒童性侵犯者[12]。

一些戀童者並不性侵犯兒童[9][5][15][6]。研究者對這類人群知之甚少,因為大多數戀童研究都使用罪犯或臨床樣本,而这可能不能如实反映一般日常的情況[109]。研究者邁克爾·塞圖表示兒童性侵犯罪犯研究亦同樣不能如实反映真实情況,因為其他反社會人格特徵會使戀童者更有可能猥褻兒童,造成樣本偏差。他指出具有下列特點的戀童者較不可能性侵犯兒童:「對別人的感情敏感、做事深思熟虑、規避風險、不煙不酒,以及支持社會規範和法律[6]。」2015年的一項研究表明,性侵犯兒童的戀童者與不性侵犯兒童的神经構造具有差異。性侵犯兒童的戀童者擁有神經缺陷,顯示其大腦抑制區遭到破坏;而不性侵犯兒童的戀童者則没这种情況[110]。

亞伯(Abel)等人以及沃德(Ward)等人分别於1985年及1995年指出,戀童和非戀童的兒童性侵犯者之間有着許大分别。他們指出非戀童的犯罪者傾向於在受到壓力時犯罪、犯罪亦發生得較后期、受害人數較少,且多为家屬;戀童的犯罪者往往在年齡較小的時候就開始犯罪、犯罪的隱蔽性較強、受害人數一般較多,且多为非家屬;他們还会出現支持犯罪的價值觀或信念[111]。一項研究發現戀童的女童性侵犯者平均性侵犯1.3名女童,男童性侵犯者則平均性侵犯4.4名男童[105]。不論戀童與否,兒童性侵犯者一般会採用各种各樣的方法去誘使兒童跟自己發生性關係,有些會跟受害者承诺送禮物给他/她,有些則下藥、灌酒,以及以暴力來威脅受害者[112]。

歷史

恋童估計自古有之[113],但直到19世纪后期以前一直没有正式的命名、定義,以及研究。戀童慾(paedophilia erotica)這個單詞是由維也納精神病學家理查德·馮·克拉夫特-埃平於1896年在一篇論文上提出,但一直没有在其著作《性精神變態》中提及[114],直到德文的第十版才提及之[115]。許多著者曾在此期間對克拉夫特-埃平的診斷标準進行了預計[115]。這個詞語出現在標題為“針對14歲以下兒童的性侵犯(Violation of Individuals Under the Age of Fourteen)”的章節中,其定義側重於在法醫精神病學中對兒童性犯罪者的解釋。克拉夫特-埃平介紹幾種兒童性犯罪者的類型,將他們分為心理病理和非心理病理的起源,并推測了幾個偶然因素可能會導致兒童遭受性暴力。[114]

克拉夫特-埃平在其著作《性精神變態》中提到了戀童慾的類型。他寫道,他在他的職業生涯里只遇到了四次病例。他簡要地描述了這些病例,并歸納出三種常見的特點:

- 患者可能是因為遺傳原因患病;

- 患者會認為兒童擁有主要的性吸引力,而不是成年人;

- 患者通常並不與孩子發生性關係,而是與孩子之間有一些不恰當的接觸或者將孩子引導到這種不道德的關係中[116]。

他還提到了幾件有成年婦女的戀童癖案例(由其他醫師提供),同時也認為同性戀者性侵犯兒童的情況較为常見[114] 。(但現有證據否定了此一説法[117])他進一步闡釋了這一點,他認為那些罹患生理或心理疾病而對兒童產生虐待行為的成年人並不是真正的戀童癖。而在這種案例中,受害者往往是青春期少年或更大一點的青少年。隨後他更以接觸兒童性幻覺者(pseudopaedophilia)為例來闡釋其中的關係,他表示“那種失去自慰樂趣而轉向對兒童性接觸而獲得快感的成年男性”更為常見[114]。

奧地利神經病學家西格蒙德·弗洛伊德在其1905年的著作《性學三論》中將一個章節的標題命名為“以未性成熟者與動物為性對象(The Sexually immature and Animals as Sexual objects)”。他寫道,純粹的戀童癖是極其罕見的,其中大多數人只是偶爾將青春期前的兒童作為性對象。他認為軟弱的人或具有某種貪欲的人更容易成為戀童癖的慾望對象[118]。

1908年,瑞士神經解剖學家和精神病學家奧古斯特·福勒尓建議將“對兒童的性慾”現象簡寫為“戀童色情(Pederosis)”。與克拉夫特-埃平的研究相似,福勒尓比較了罹患痴呆症或其他腦部器質性疾病患者的偶發性性虐待與真正優先選擇或偶爾獨佔對兒童性慾患者之間的聯繫。然而,他並不同意克拉夫特-埃平結論,他認為那些對兒童擁有主要的性吸引力,或只有兒童才有性吸引力的人是不可糾正或治愈的[119]。

在20世紀初,戀童這個詞語和定義被醫學界廣泛接受和採用,當時的許多醫學字典(例如1918年出版的第五版《斯特德曼醫學字典》)都用了這個術語。1952年,它被列入到第一版的《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》。[120] 第一版和第二版的《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》將戀童癖列為“性慾倒錯”的一個亞種,但是並沒有就此給出診斷標準。在第三版的《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》中,則對戀童癖進行了詳細闡釋并給出了診斷標準。[121] 而在1987年修訂出版的第三版《精神疾病診斷與統計手冊》修訂版中保留了第三本中對戀童癖的闡釋,但是卻更新和拓寬了對其診斷的條件和標準。[122]

法律與法庭心理學

定義

戀童並非法律上的用語[12],認为兒童擁有性吸引力亦非違法[5]。戀童者在法律界上有时会非正式地用於代指任何犯有與法定未成年人有關的性罪行的人。相关罪名包括兒童性侵犯、兒童性誘拐、 法定强奸、纏擾未成年人、管有兒童色情作品、以及故意暴露。 英國的虐童調查隊專門從事相關的網絡調查和執法工作[123]。一些法醫學文獻会使用戀童一詞來代指對兒童下手的性罪犯,即使犯罪者不对兒童擁有主要的性偏好[124]。然而美國聯邦調查局的特務肯尼斯·蘭寧(Kenneth Lanning)会把戀童者和兒童性侵犯者分开看待,且能指出兩者的不同之处[125]。

預防性拘留

美國在經歷堪薩斯訴亨德里克斯一案後,被診斷患有某些精神障礙的性犯罪者可因某些州的法律,而遭到無限期的預防性拘留,特別是戀童癖[20](此法及後一般稱為《高危險連續性罪犯法案》)。2006年通過的《亞當˙華爾斯兒童保護安全法案》則把以上法例扩展至全美國[126]。加拿大也有類似的法規[20]。

美國最高法院在堪薩斯訴亨德里克斯案中支持把《堪薩斯法》(后來稱为《高危險連續性罪犯法案》)列為憲法。使得被認定为「精神異常」的戀童者亨德里克斯(Hendricks)遭到無限期的預防性拘留,不論州政府有否为擁有者提供治疗[127][128][129]。在美國政府訴康斯托克一案中,美國法院判定被定罪为「管有兒童色情作品」的人亦同樣適用此法,並把此法扩展至全美國,改稱为亞當˙華爾斯兒童保護安全法案[126][130]。華爾斯法案的適用对象並不只有已定罪者;所有囚犯皆適用於此法規[131]。

美國的戀童罪犯比非戀童罪犯更容易遭到預防性拘留。大约有一半遭到預防性拘留的罪犯確診為戀童癖[20]。精神科医师邁克爾·史密斯(Michael First)寫道:「既然不是所有性偏離人士都难以控制自己的行为,那麼進行診斷的医师就必須提供額外的證據去證明有預防性拘留的必要,不是僅僅基於戀童本身[132]。」

恋童與社會

恋童是最受社會污名的精神障礙之一[37]。一項研究指出,社會普遍會排斥沒有犯罪的戀童者,並對其感到憤怒、恐懼[133]。研究者認為這種態度會使戀童者的精神狀態趨向不穩定,使他們更可能性侵犯兒童,並使他們怯於尋求幫助[37]。社會學家梅蘭妮 - 安吉拉·納伊(Melanie-Angela Neuilly)和克里斯汀·佐格(Kristen Zgoba)指出,社會大眾對戀童的關注在20世紀90年代大大加劇,因当时發生了幾宗聳人聽聞的性犯罪(但性侵犯兒童率普遍下降)。他們發現在1996年之前,「戀童」這個詞在《紐約時報》和《世界報》中很少出現,1991年更是完全沒有提及[134]。

社會對性侵犯兒童的態度也同樣十分負面,有些調查甚至指出大眾認為其在道德上比謀殺更坏[135]。儘管早期的研究表明大眾對兒童性侵犯和恋童存有許多誤解以及一些不符合实際情況的想法,但2004年的一項研究指出大眾对相关議題已有一定的了解[136]。

誤用用詞

「戀童」和「戀童者」通常非正式地用於表示某名成年人對处於青春期或青春期後的青少年擁有性興趣,但这种情況下使用「戀青少年」和「戀少年」可能会較準確[12][27][137]。這種情況在馬克·福利(Mark Foley)案中更是如此, 當時大多數媒體把福利形容成恋童者,繼使《Slate》雜誌的大衛·塔勒(David Tuller)对外澄清福利不是戀童者,而是戀青少年者[138]。

大眾亦常把戀童直接用於代指「兒童性侵犯」本身[9],但相比戀童的医学定義,其明顯顯得过於广泛——戀童的医学定義是指年長的患者認為青春期前的兒童擁有主要的性吸引力[10][11]。另外还有一些情況大眾会誤用戀童此一用詞,比如達至法定年齡的年輕人與过於年老的人结成伴侣的情況[139]。研究者指出以上用例皆不精確,並要求大眾最好避免如此使用恋童此一字眼[10][27]。马约诊所亦指出戀童並非法律上的用語[12]。

戀童擁護團體

幾个戀童擁護團體在20世紀50年代末到90年代初主張最低合法性交年齡應降低至他們認为合理的标準,甚至認为年齡限制理應廢除[140][141][142],他們亦同时認为戀童不是一种精神障礙,而是一种性傾向[143],並要求兒童色情作品合法化[142]。戀童擁護團體的努力沒有獲得公眾的支持[140][142][144][145][146],而現今沒有解散的少數戀童擁護團體的會員極少,且只能通過幾個網站進行相关活動[142][146][147][148]。戀童擁護團體Virtuous Pedophiles的成員的意見與其他组織相反,他們認為性侵犯兒童是一种錯誤的行为,並應設法提高一些戀童者的相关意識[149][150] ;Virtuous Pedophiles通常不会遭視为戀童擁護團體,因為其不贊成兒童色情作品合法化及降低合法性交年齡[151]。

反戀童行動

反戀童行動的反对內容有很多,包括反對戀童者、反對戀童擁護團體,以及反對被視為與戀童有關的現象,比如兒童色情作品和性侵犯兒童[152]。大部分分類為反戀童的直接行動都会涉及對性犯罪者的示威、反對戀童擁護團體提倡成人和兒童之間性活動合法化,以及反對向未成年人徵求性行為的互聯網用戶[153][154][155][156]。

媒體對戀童的高度關注会導致大眾出現道德恐慌,特別是與撒旦儀式和日間托兒有關的戀童事件被报導出來以后[157]。有報導指出部分私刑殺害是為了回應公眾對被定罪或懷疑兒童性侵犯罪犯的關注。2000年的英國媒體曾宣傳「點名羞辱」懷疑戀童者,结果數以百計的居民紛紛上街抗議和指責疑似戀童者,最終相关抗議行動升级為需要警方介入的暴力行為[153]。

参见

- 童妓

- 兒童色情

- 蘿莉控

- 正太控

- 戀少年

參考文獻

^ 1.01.11.21.31.41.51.61.71.81.9 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013 [2013-07-25].

^ 2.02.12.22.32.4 See section F65.4 Paedophilia. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World (PDF). World Health Organization/ICD-10. 1993 [2012-10-10].B. A persistent or a predominant preference for sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children. C. The person is at least 16 years old and at least five years older than the child or children in B.

^ 3.03.13.23.3 Cutler, Brian L. Encyclopedia of Psychology and Law. SAGE. 2008: 549. ISBN 978-1-4129-5189-0.

^ 4.04.1 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 101.

^ 5.05.15.25.35.45.55.65.75.85.9 Fagan PJ, Wise TN, Schmidt CW, Berlin FS. Pedophilia. JAMA. November 2002, 288 (19): 2458–65. PMID 12435259. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2458.

^ 6.006.016.026.036.046.056.066.076.086.096.106.116.126.136.146.156.166.17 Seto MC. Pedophilia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009, 5: 391–407. PMID 19327034. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153618.

^ Kail, RV; Cavanaugh JC. Human Development: A Lifespan View 5th. Cengage Learning. 2010: 296. ISBN 0495600377.

^ 8.08.18.2 ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. World Health Organization/ICD-11. See section 6D32 Pedophilic disorder. 2018 [2018-07-07].Pedophilic disorder is characterized by a sustained, focused, and intense pattern of sexual arousal—as manifested by persistent sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, or behaviours—involving pre-pubertal children. In addition, in order for Pedophilic Disorder to be diagnosed, the individual must have acted on these thoughts, fantasies or urges or be markedly distressed by them. This diagnosis does not apply to sexual behaviours among pre- or post-pubertal children with peers who are close in age.

^ 9.09.19.29.3 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: vii.

^ 10.010.110.210.310.4 Ames MA, Houston DA. Legal, social, and biological definitions of pedophilia. Arch Sex Behav. August 1990, 19 (4): 333–42. PMID 2205170. doi:10.1007/BF01541928.

^ 11.011.111.2 Lanning, Kenneth. Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis (PDF). National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. 2010. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-12-24).

^ 12.012.112.212.312.412.5 Hall RC, Hall RC. A profile of pedophilia: definition, characteristics of offenders, recidivism, treatment outcomes, and forensic issues. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007, 82 (4): 457–71. PMID 17418075. doi:10.4065/82.4.457.

^ 13.013.113.2 Blaney, Paul H.; Millon, Theodore. Oxford Textbook of Psychopathology (Oxford Series in Clinical Psychology) 2nd. Oxford University Press, USA. 2009: 528. ISBN 0-19-537421-5.Some cases of child molestation, especially those involving incest, are committed in the absence of any identifiable deviant erotic age preference.

^ 14.014.114.214.3 Edwards, M. (1997) "Treatment for Paedophiles; Treatment for Sex Offenders". Paedophile Policy and Prevention, Australian Institute of Criminology Research and Public Policy Series (12), 74-75.

^ 15.015.115.2 Feelgood S, Hoyer J. Child molester or paedophile? Sociolegal versus psychopathological classification of sexual offenders against children. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2008, 14 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1080/13552600802133860.

^ 16.016.1 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 72–74.

^ Goldman, Howard H. Review of General Psychiatry. McGraw-Hill Professional Psychiatry. 2000: 374. ISBN 0-8385-8434-9.

^ 18.018.118.218.318.4 Lisa J. Cohen, PhD and Igor Galynker, MD, PhD. Psychopathology and Personality Traits of Pedophiles. Psychiatric Times. 2009-06-08 [2014-03-07].

^ 19.019.1 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia: Psychopathology and Theory. (编) Laws, D. Richard. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment, 2nd edition. The Guilford Press. 2008: 168.

^ 20.020.120.220.3 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: xii, 186.

^ Liddell, H.G., and Scott, Robert (1959). Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon. ISBN 0-19-910206-6.

^ 22.022.1 Sarah D. Goode. Understanding and Addressing Adult Sexual Attraction to Children: A Study of Paedophiles in Contemporary Society. Routledge. 2009-07-07: 13–14. ISBN 978-1-135-25804-7.

^ 23.023.1 Laws, D. Richard; William T. O'Donohue. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. Guilford Press. 2008: 176. ISBN 1-59385-605-9.

^ Greenberg DM, Bradford J, Curry S. Infantophilia--a new subcategory of pedophilia?: a preliminary study (PDF). Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995, 23 (1): 63–71. PMID 7599373. .

^ Blanchard R, Lykins AD, Wherrett D, Kuban ME, Cantor JM, Blak T, Dickey R, Klassen PE. Pedophilia, hebephilia, and the DSM-V. Arch Sex Behav. June 2009, 38 (3): 335–50. PMID 18686026. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9399-9.

^ 26.026.126.2 APA DSM-5 | U 03 Pedophilic Disorder

^ 27.027.127.2 S. Berlin, Frederick. Interview with Frederick S. Berlin, M.D., Ph.D. Office of Media Relations. [2008-06-27]. (原始内容存档于2011-06-23).

^ Berlin, Fred S. Treatments to Change Sexual Orientation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000, 157 (5): 838–838 [2014-12-10]. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.838.

^ Wetzstein, Cheryl. APA to correct manual: Pedophilia is not a ‘sexual orientation’. The Washington Times. 2013-10-31 [2014-02-14].

^ Marshall WL. The relationship between self-esteem and deviant sexual arousal in nonfamilial child molesters. Behavior Modification. 1997, 21 (1): 86–96. PMID 8995044. doi:10.1177/01454455970211005.

^ Okami, P. & Goldberg, A. (1992). "Personality Correlates of Pedophilia: Are They Reliable Indicators?", Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 297–328. "For example, because an unknown percentage of true pedophiles may never act on their impulses or may never be arrested, forensic samples of sex offenders against minors clearly do not represent the population of "pedophiles", and many such persons apparently do not even belong to the population of "pedophiles"."

^ 32.032.1 Seto MC. Pedophilia and sexual offenses against children. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2004, 15: 321–61. PMID 16913283.

^ Cohen LJ, McGeoch PG, Watras-Gans S, Acker S, Poznansky O, Cullen K, Itskovich Y, Galynker I. Personality impairment in male pedophiles (PDF). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. October 2002, 63 (10): 912–9. PMID 12416601. doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n1009.

^ Strassberg, Donald S., Eastvold, Angela, Kenney, J. Wilson, Suchy, Yana. Psychopathy among pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012, 36: 379–382. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.018.

^ Suchy, Yana; Whittaker, Wilson J.; Strassberg, Donald S.; Eastvold, Angela. Facial and prosodic affect recognition among pedophilic and nonpedophilic criminal child molesters. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2009, 21 (1): 93–110. doi:10.1177/1079063208326930.

^ Wilson G. D.; Cox D. N. Personality of paedophile club members. Personality and Individual Differences. 1983, 4 (3): 323–329. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(83)90154-X.

^ 37.037.137.2 Jahnke, S., Hoyer, J. Stigma against people with pedophilia: A blind spot in stigma research?. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2013, 25: 169–184. doi:10.1080/19317611.2013.795921.

^ Lawson L. Isolation, gratification, justification: offenders' explanations of child molesting. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2003, 24 (6–7): 695–705. PMID 12907384. doi:10.1080/01612840305328.

^ Mihailides S, Devilly GJ, Ward T. Implicit cognitive distortions and sexual offending. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2004, 16 (4): 333–350. PMID 15560415. doi:10.1177/107906320401600406.

^ 40.040.1 Seto MC, Cantor JM, Blanchard R. Child pornography offenses are a valid diagnostic indicator of pedophilia. J Abnorm Psychol. August 2006, 115 (3): 610–5. PMID 16866601. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.610.The results suggest child pornography offending is a stronger diagnostic indicator of pedophilia than is sexually offending against child victims

^ 41.041.1 Lanning, Kenneth V. Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis, Fifth Edition (PDF). National Center for Missing and Exploited Children: 79. 2010. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-12-24).

^ Crosson-Tower, Cynthia. Understanding child abuse and neglect. Allyn & Bacon. 2005: 208. ISBN 0-205-40183-X.

^ Richard Wortley; Stephen Smallbone. Child Pornography on the Internet (PDF). Problem-Oriented Guides for Police: 14–16. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-01-07).

^ Levesque, Roger J. R. Sexual Abuse of Children: A Human Rights Perspective. Indiana University. 1999: 64. ISBN 0-253-33471-3.

^ Crosson-Tower, Cynthia. Understanding child abuse and neglect. Allyn & Bacon. 2005: 198–200. ISBN 0-205-40183-X.

^ Lanning, Kenneth V. Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis, Fifth Edition (PDF). National Center for Missing and Exploited Children: 107. 2010. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-12-24).

^ Quayle, E.; Taylor, M. Child pornography and the internet: Assessment Issues. British Journal of Social Work. 2002, 32: 867. doi:10.1093/bjsw/32.7.863.

^ 48.048.1 Blanchard R.; Kolla N. J.; Cantor J. M.; Klassen P. E.; Dickey R.; Kuban M. E.; Blak T. IQ, handedness, and pedophilia in adult male patients stratified by referral source. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2007, 19 (3): 285–309. doi:10.1177/107906320701900307.

^ 49.049.149.2 Cantor JM, Blanchard R, Christensen BK, Dickey R, Klassen PE, Beckstead AL, Blak T, Kuban ME. Intelligence, memory, and handedness in pedophilia. Neuropsychology. 2004, 18 (1): 3–14. PMID 14744183. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.18.1.3.

^ Cantor JM, Blanchard R, Robichaud LK, Christensen BK. Quantitative reanalysis of aggregate data on IQ in sexual offenders. Psychological Bulletin. 2005, 131 (4): 555–568. PMID 16060802. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.555.

^ Cantor JM, Klassen PE, Dickey R, Christensen BK, Kuban ME, Blak T, Williams NS, Blanchard R. Handedness in pedophilia and hebephilia. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2005, 34 (4): 447–459. PMID 16010467. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-4344-7.

^ Bogaert AF. Handedness, criminality, and sexual offending. Neuropsychologia. 2001, 39 (5): 465–469. PMID 11254928. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(00)00134-2.

^ Cantor JM, Kuban ME, Blak T, Klassen PE, Dickey R, Blanchard R. Grade failure and special education placement in sexual offenders' educational histories. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006, 35 (6): 743–751. PMID 16708284. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9018-6.

^ Cantor JM, Kuban ME, Blak T, Klassen PE, Dickey R, Blanchard R. Physical height in pedophilic and hebephilic sexual offenders. Sex Abuse. 2007, 19 (4): 395–407. PMID 17952597. doi:10.1007/s11194-007-9060-5.

^ McPhail, Ian V.; Cantor, James M. Pedophilia, Height, and the Magnitude of the Association: A Research Note. Deviant Behavior. 2015-04-03, 36 (4): 288–292. ISSN 0163-9625. doi:10.1080/01639625.2014.935644.

^ 56.056.1 Blanchard R, Christensen BK, Strong SM, Cantor JM, Kuban ME, Klassen P, Dickey R, Blak T. Retrospective self-reports of childhood accidents causing unconsciousness in phallometrically diagnosed pedophiles. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2002, 31 (6): 511–526. PMID 12462478. doi:10.1023/A:1020659331965.

^ Blanchard R, Kuban ME, Klassen P, Dickey R, Christensen BK, Cantor JM, Blak T. Self-reported injuries before and after age 13 in pedophilic and non-pedophilic men referred for clinical assessment. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003, 32 (6): 573–581. PMID 14574100. doi:10.1023/A:1026093612434.

^ 58.058.1 Cantor JM, Kabani N, Christensen BK, Zipursky RB, Barbaree HE, Dickey R, Klassen PE, Mikulis DJ, Kuban ME, Blak T, Richards BA, Hanratty MK, Blanchard R. Cerebral white matter deficiencies in pedophilic men. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008, 42 (3): 167–183. PMID 18039544. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.10.013.

^ Schiffer B, Peschel T, Paul T, Gizewski E, Forsting M, Leygraf N, Schedlowski M, Krueger TH. Structural brain abnormalities in the frontostriatal system and cerebellum in pedophilia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007, 41 (9): 753–62. PMID 16876824. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.003.

^ Schiltz K, Witzel J, Northoff G, Zierhut K, Gubka U, Fellmann H, Kaufmann J, Tempelmann C, Wiebking C, Bogerts B. Brain pathology in pedophilic offenders: Evidence of volume reduction in the right amygdala and related diencephalic structures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007, 64 (6): 737–746. PMID 17548755. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.737.

^ Joyal, CC, Plante-Beaulieu, J. & De Chanterac, A. The neuropsychology of sexual offenders: A meta-analysis.. Journal of Sexual Abuse. 2014, 26: 149–177. doi:10.1177/1079063213482842.The distinction between nonpedophilic child molesters and exclusive pedophile child molesters, for instance, could be crucial in neuropsychology because the latter seem to be less cognitively impaired (Eastvold et al., 2011; Schiffer & Vonlaufen, 2011; Suchy et al., 2009). Pedophilic child molesters might perform as well as controls (and better than nonpedophilic child molesters) on a wide variety of neuropsychological measures when mean IQ and other socioeconomic factors are similar (Schiffer & Vonlaufen, 2011). In fact, some pedophiles have higher IQ levels and more years of education compared with the general population (Langevin et al., 2000; Lothstein, 1999; Plante & Aldridge, 2005).

^ Schiffer, B., & Vonlaufen, C. Executive dysfunctions in pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters.. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011, 8: 1975–1984. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02140.x.

^ Gaffney GR, Lurie SF, Berlin FS. Is there familial transmission of pedophilia?. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. September 1984, 172 (9): 546–8. PMID 6470698. doi:10.1097/00005053-198409000-00006.

^ Azizian, Allen. Cognitional Impairment: Is There a Role for Cognitive Assessment in the Treatment of Individuals Civilly Committed Pursuant to the Sexually Violent Predator Act? (PDF). Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2015, (1–15) [2016-04-27]. doi:10.1177/1079063215570757. Archived from the original on 2015-06-11.

^ Walter; 等. Pedophilia Is Linked to Reduced Activation in Hypothalamus and Lateral Prefrontal Cortex During Visual Erotic Stimulation. Biological Psychiatry. 2007, 62: 698–701. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.018. 引文格式1维护:显式使用等标签 (link)

^ Schiffer B, Paul T, Gizewski E, Forsting M, Leygraf N, Schedlowski M, Kruger TH. Functional brain correlates of heterosexual paedophilia. NeuroImage. May 2008, 41 (1): 80–91. PMID 18358744. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.008.

^ Blanchard, R., Cantor, J. M., & Robichaud, L. K. (2006). Biological factors in the development of sexual deviance and aggression in males. In Howard E. Barbaree; William L. Marshall. The Juvenile Sex Offender. Guilford Press. 2008-06-19: 77. ISBN 978-1-59385-978-7.

^ Rahman Q, Symeonides DJ. Neurodevelopmental Correlates of Paraphilic Sexual Interests in Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. February 2007, 37 (1): 166–172. PMID 18074220. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9255-3.

^ 69.069.1 See section F65.4 Paedophilia. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. ICD-10. [2012-11-17].

^ Pedophilia 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2006-05-08. DSM at the Medem Online Medical Library

^ 71.071.171.271.371.4 Studer LH, Aylwin AS. Pedophilia: The problem with diagnosis and limitations of CBT in treatment. Medical Hypotheses. 2006, 67 (4): 774–781. PMID 16766133. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.030.

^ O'Donohue W, Regev LG, Hagstrom A. Problems with the DSM-IV diagnosis of pedophilia. Sex Abuse. 2000, 12 (2): 95–105. PMID 10872239. doi:10.1023/A:1009586023326.

^ Green R. Is pedophilia a mental disorder?. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2002, 31: 467–471. doi:10.1023/a:1020699013309. (原始内容存档于2010-10-12).

^ Moulden HM, Firestone P, Kingston D, Bradford J. Recidivism in pedophiles: an investigation using different diagnostic methods. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2009, 20 (5): 680–701. doi:10.1080/14789940903174055.

^ Blanchard R. The DSM diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Arch Sex Behav. April 2010, 39 (2): 304–16. PMID 19757012. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9536-0.

^ Blanchard R, Lykins AD, Wherrett D, Kuban ME, Cantor JM, Blak T, Dickey R, Klassen PE. Pedophilia, Hebephilia, and the DSM-V (pdf). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009, 38 (3): 335–350. PMID 18686026. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9399-9.

^ Karen Franklin. Psychiatry Rejects Novel Sexual Disorder "Hebephilia". USA: Psychology Today. 2012-12-02.

^ 78.078.1 Paraphilic Disorders (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013 [2013-07-08]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-07-24).

^ O'Donohue W. A critique of the proposed DSM-V diagnosis of pedophilia. Arch Sex Behav. Jun 2010, 39 (3): 587–90. PMID 20204487. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9604-5.

^ 80.080.1 Barbaree, H. E., and Seto, M. C. (1997). Pedophilia: Assessment and Treatment. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. 175-193.

^ Seto MC, Ahmed AG. Treatment and management of child pornography use. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2014, 37 (2): 207–214. PMID 24877707. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.03.004.

^ Camilleri, Joseph A., and Quinsey, Vernon L. Pedophilia: Assessment and Treatment. (编) Laws, D. Richard. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment, 2nd edition. The Guilford Press. 2008: 193.

^ Berlin, Fred S. Treatments to Change Sexual Orientation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000, 157: 838. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.838. .

^ Berlin, Fred S. Peer Commentaries on Green (2002) and Schmidt (2002) - Pedophilia: When Is a Difference a Disorder? (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. December 2002, 31 (6): 479–480 [2009-12-17]. doi:10.1023/A:1020603214218. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-10-29).

^ Rice ME, Harris GT. The size and signs of treatment effects in sex offender therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003, 989: 428–40. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07323.x.

^ 86.086.1 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 171.

^ 87.087.1 Dennis JA, Khan O, Ferriter M, Huband N, Powney MJ, Duggan C. Psychological interventions for adults who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012, (12). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007507.pub2.

^ Lösel F, Schmucker M. The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005, 1 (1): 117–46. doi:10.1007/s11292-004-6466-7.

^ Hanson RK, Gordon A, Harris AJ, Marques JK, Murphy W, 等. First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse. 2002, 14 (2): 169–94. doi:10.1177/107906320201400207.

^ Rice ME, Harris GT. Treatment for adult sex offenders: may we reject the null hypothesis?. (编) Harrison K, Rainey B. Handbook of Legal & Ethical Aspects of Sex Offender Treatment & Management. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 2012.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 175.

^ Barbaree, H. E., Bogaert, A. F., & Seto, M. C. (1995). Sexual reorientation therapy for pedophiles: Practices and controversies. In L. Diamant & R. D. McAnulty (Eds.), The psychology of sexual orientation, behavior, and identity: A handbook (pp. 357–383). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

^ Barbaree, H. C., & Seto, M. C. (1997). Pedophilia: Assessment and treatment. In D. R. Laws & W. T. O'Donohue (eds.), Sexual deviance: Theory, assessment and treatment (pp. 175–193). New York: Guildford Press.

^ Maguth Nezu C.; Fiore A. A.; Nezu A. M. Problem Solving Treatment for Intellectually Disabled Sex Offenders. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2006, 2: 266–275. doi:10.1002/9780470713488.ch6.

^ 95.095.1 Camilleri, Joseph A., and Quinsey, Vernon L. Pedophilia: Assessment and Treatment. (编) Laws, D. Richard. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment, 2nd edition. The Guilford Press. 2008: 199–200.

^ 96.096.1 Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 177–181.

^ Cohen LJ, Galynker II. Clinical features of pedophilia and implications for treatment. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2002, 8 (5): 276–89. PMID 15985890. doi:10.1097/00131746-200209000-00004.

^ Guay, DR. Drug treatment of paraphilic and nonparaphilic sexual disorders. Clinical Therapeutics. 2009, 31 (1): 1–31. PMID 19243704. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.009.

^ 99.099.1 Anti-androgen therapy and surgical castration. Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers. 1997. (原始内容存档于2011-08-29).

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 181–182, 192.

^ Prague Urged to End Castration of Sex Offenders. DW.DE. 2009-02-05 [2015-01-19].

^ Howells, K. (1981). "Adult sexual interest in children: Considerations relevant to theories of aetiology", Adult sexual interest in children. 55-94.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 4.

^ Suchy, Y., Whittaker, W.J., Strassberg, D., & Eastvold, A. Facial and Prosodic Affect Recognition Among Pedophilic and Nonpedophilic Criminal Child Molesters. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2009, 21 (1): 93–110. doi:10.1177/1079063208326930.

^ 105.0105.1 Schaefer, G. A., Mundt, I. A., Feelgood, S., Hupp, E., Neutze, J., Ahlers, Ch. J., Goecker, D., Beier, K. M. Potential and Dunkelfeld offenders: Two neglected target groups for prevention of child sexual abuse. International Journal of Law & Psychiatry. 2010, 33 (3): 154–163. PMID 20466423. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.03.005.

^ Seto, M. C., Cantor, J. M., & Blanchard, R. Child pornography offenses are a valid diagnostic indicator of pedophilia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006, 115: 612. PMID 16866601. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.115.3.610.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 123.

^ Blanchard, R., Kuban, M. E., Blak, T., Cantor, J. M., Klassen, P., & Dickey, R. Phallometric comparison of pedophilic interest in nonadmitting sexual offenders against stepdaughters, biological daughters, other biologically related girls, and unrelated girls. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2006, 18 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1177/107906320601800101.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 47–48, 66.

^ Kärgel, C., Massau, C., Weiß, S., Walter, M., Kruger, T. H., & Schiffer, B. Diminished Functional Connectivity on the Road to Child Sexual Abuse in Pedophilia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2015, 12: 783–795. doi:10.1111/jsm.12819.

^ Abel, G. G., Mittleman, M. S., & Becker, J. V. (1985). "Sex offenders: Results of assessment and recommendations for treatment". In M. H. Ben-Aron, S. J. Hucker, & C. D. Webster (Eds.), Clinical criminology: The assessment and treatment of criminal behavior (pp. 207–220). Toronto, Canada: M & M Graphics.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 64, 189.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: 13.

^ 114.0114.1114.2114.3 Von Krafft-Ebing, Richard. Psychopathia Sexualis. Translated to English by Francis Joseph Rebman. Medical Art Agency. 1922: 552–560. ISBN 1-871592-55-0.

^ 115.0115.1 Janssen, D.F. "Chronophilia": Entries of Erotic Age Preference into Descriptive Psychopathology. Medical History. 2015, 59 (4): 575–598. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 4595948. PMID 26352305. doi:10.1017/mdh.2015.47.

^ Roudinesco, Élisabeth (2009). Our dark side: a history of perversion, p. 144. Polity, ISBN 978-0-7456-4593-3

^ Jim Burroway. Are Gays A Threat To Our Children?. Box Turtle Bulletin.

^ Freud, Sigmund Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex Mobi Classics pages 18-20

^ Forel, Auguste. The Sexual Question: A scientific, psychological, hygienic and sociological study for the cultured classes. Translated to English by C.F. Marshall, MD. Rebman. 1908: 254–255.

^ American Psychiatric Association Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 1st. 華盛頓特區: 美國精神病學會. 1952: 39.

^ American Psychiatric Association: Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 3rd. 華盛頓特區: 美國精神病學會. 1980: 271.

^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III-R. 華盛頓特區: 美國精神病學會. 1987. ISBN 0-89042-018-1.

^ Child abuse investigation impact (PDF). Metropolitan Police Service (met.police.uk). [2014-04-18].

^ Holmes, Ronald M. Profiling Violent Crimes: An Investigative Tool. Sage Publications. ISBN 1-4129-5998-5.

^ Lanning, Kenneth V. Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis, Fifth Edition (PDF). National Center for Missing and Exploited Children: 16–17, 19–20. 2010. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-12-24).

^ 126.0126.1 Holland, Jesse J. Court: Sexually dangerous can be kept in prison. Associated Press. 2010-05-17 [2010-05-16]. (原始内容存档于2010-05-20).

^ Psychological Evaluation for the Courts, Second Edition - A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals and Lawyers - 9.04 Special Sentencing Provisions (b) Sexual Offender Statutes. Guilford.com. [2007-10-19]. [永久失效連結]

^ Cripe, Clair A; Pearlman, Michael G. Legal aspects of corrections management. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7637-2545-7.

^ Ramsland, Katherine M; McGrain, Patrick Norman. Inside the minds of sexual predators. 2010. ISBN 978-0-313-37960-4.

^ Liptak, Adam. Extended Civil Commitment of Sex Offenders Is Upheld. The New York Times. 2010-05-17.

^ Barker, Emily. The Adam Walsh Act: Un-Civil Commitment. Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly. 2009, 37 (1): 145. SSRN 1496934.

^ First, Michael B., Halon, Robert L. Use of DSM Paraphilia Diagnoses in Sexually Violent Predator Commitment Cases (PDF). Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2008, 36 (4): 450.

^ Jahnke, S., Imhoff, R., Hoyer, J. Stigmatization of People with Pedophilia: Two Comparative Surveys. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015, 44 (1): 21–34. PMID 24948422. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0312-4.

^ Neuillya, M.; Zgobab, K. Assessing the Possibility of a Pedophilia Panic and Contagion Effect Between France and the United States. Victims & Offenders. 2006, 1 (3): 225–254. doi:10.1080/15564880600626122.

^ Seto, Michael. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2008: viii.

^ McCartan, K. 'Here There Be Monsters': the public's perception of paedophiles with particular reference to Belfast and Leicester. Medicine, Science and the Law. 2004, 44 (4): 327–42. PMID 15573972. doi:10.1258/rsmmsl.44.4.327.

^ Pedophilia. Encyclopædia Britannica. [2015-07-19].

^ Tuller, David. What To Call Foley. The congressman isn't a pedophile. He's an ephebophile. Slate. 2006-10-04 [2010-10-17].

^ Guzzardi, Will. Andy Martin, GOP Senate Candidate, Calls Opponent Mark Kirk A "De Facto Pedophile". Huffington Post. 2010-01-06 [2010-01-15].

^ 140.0140.1 Jenkins, Philip. Decade of Nightmares: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America. Oxford University Press. 2006: 120. ISBN 0-19-517866-1.

^ Spiegel, Josef. Sexual Abuse of Males: The Sam Model of Theory and Practice. Routledge. 2003: 5, p9. ISBN 1-56032-403-1.

^ 142.0142.1142.2142.3 Eichewald, Kurt. From Their Own Online World, Pedophiles Extend Their Reach. New York Times. 2006-08-21.

^ Frits Bernard. The Dutch Paedophile Emancipation Movement. Paidika: the Journal of Paedophilia. (原始内容存档于2016-01-02).Heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality and paedophilia should be considered equally valuable forms of human behavior.

^ Jenkins, Philip. Intimate Enemies: Moral Panics in Contemporary Great Britain. Aldine Transaction. 1992: 75. ISBN 0-202-30436-1.In the 1970s, the pedophile movement was one of several fringe groups whose cause was to some extent espoused in the name of gay liberation.

^ Stanton, Domna C. Discourses of Sexuality: From Aristotle to AIDS. University of Michigan Press. 1992: 405. ISBN 0-472-06513-0.

^ 146.0146.1 Hagan, Domna C.; Marvin B. Sussman. Deviance and the family. Haworth Press. 1988: 131. ISBN 0-86656-726-7.

^ Benoit Denizet-Lewis (2001). "Boy Crazy", Boston Magazine.

^ Trembaly, Pierre (2002). "Social interactions among paedophiles" 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2009-11-22..

^ Virtuous Pedophiles - Welcome. virped.org. [2015-09-12].

^ Clark-Flory, Tracy. Meet pedophiles who mean well. Salon. 2012-06-20 [2015-09-12].

^ Virtuous Pedophiles. Virtuous Pedophiles.

^ Global Crime Report - INVESTIGATION - Child porn and the cybercrime treaty part 2 - BBC World Service. bbc.co.uk.

^ 153.0153.1 Families flee paedophile protests August 9, 2000. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

^ Dutch paedophiles set up political party, May 30, 2006. Retrieved January 2008.

^ The Perverted Justice Foundation Incorporated - A note from our foundation to you. Perverted-Justice. [2012-03-16].

^ Salkin, Allen; Happy Blitt. Web Site Hunts Pedophiles and TV Goes Along. The New York Times (New York, New York). 2006-12-13 [2012-03-16].'Every waking minute he's on that computer,' said his mother, Mary Erck-Heard, 46, who raised her son after they fled his father, whom she described as alcoholic. Mr. Von Erck legally changed his name from Phillip John Eide, taking his maternal grandfather's family name, Erck, and adding the Von.

^ Jewkes Y. Media and crime. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage. 2004: 76–77. ISBN 0-7619-4765-5.

外部链接

| 分類 |

|

|---|

認識『性倒錯』(Paraphilia)(繁体中文)- Understanding MRI research on pedophilia

- Pedophilia: Myths, Realities and Treatments

Indictment from Operation Delego (PDF) (Archive)

Virtuous Pedophiles, online support for non-offending pedophiles working to remain offence-free.

延伸閲讀

- Gladwell, Malcolm. "In Plain View." ("Jerry Sandusky and the Mind of a Pedophile") The New Yorker. September 24, 2012.

- Philby, Charlotte. "Female sexual abuse: The untold story of society's last taboo." The Independent. Saturday August 8, 2009.

- Bleyer, Jennifer. "How Can We Stop Pedophiles? Stop treating them like monsters." Slate. Monday September 24, 2012.

- Fong, Diana. Editor: Nancy Isenson. "'If I'm attracted to children, I must be a monster'." '[Die Welt. May 29, 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|