Theravada

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Theravādin monk meditating while seated in the Lotus position beside Sirikit Dam (Thailand)

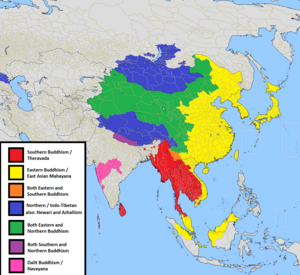

Map showing the three major Buddhist divisions in Tibet, Mongolia, Nepal, East and Southeast Asia.

Part of a series on |

| Theravāda Buddhism |

|---|

|

Countries

|

Texts

|

History

|

Doctrine

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

History

|

|

Buddhist texts

|

Practices

|

Nirvāṇa

|

Traditions

|

Buddhism by country

|

|

Theravāda (/ˌtɛrəˈvɑːdə/; Pāli, lit. "School of the Elders"[1][2]) is the most ancient branch of Buddhism still extant today,[1][2] and the one that preserved the teachings of Gautama Buddha in the Pāli Canon,[1][2] its doctrinal core.[1] The Pāli Canon is the only complete Buddhist canon which survives in Pāli, a classical Indic Language which serves as both sacred language[2] and lingua franca of Theravāda Buddhism.[3] Another feature of Theravāda is its tendency to be very conservative with regard to matters of doctrine and monastic discipline.[4] As a distinct school of early Buddhism, Theravāda Buddhism developed in Sri Lanka and subsequently spread to the rest of Southeast Asia.

Theravāda also includes a rich diversity of traditions and practices that have developed over its long history of interactions with varying cultures and religious communities. It is the dominant form of religion in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, and is practiced by minority groups in India, Bangladesh, China, Nepal, and Vietnam. In addition, the diaspora of all of these groups as well as converts around the world practice Theravāda Buddhism. Contemporary expressions include Buddhist modernism, the Vipassana movement, and the Thai Forest Tradition.

Contents

1 Adherents

2 History

2.1 Origins

2.2 Transmission to Sri Lanka

2.3 Pali textual tradition

2.4 Theravāda subdivisions

2.5 Mahāyāna influences

2.6 Reign of Parakramabahu I

2.7 Lineage of nuns

2.8 Spread to Southeast Asia

2.9 Late innovations and esotericism

2.10 Modernisation and spread to the West

2.10.1 Reaction against Western colonialism

2.10.2 Sri Lanka

2.10.3 Thailand

2.10.4 Myanmar

2.10.5 Modern developments

3 Doctrine

3.1 Dhamma theory

3.2 Doctrinal differences with other Buddhist schools

3.2.1 View of the Arhat

3.2.2 View of the Buddha

3.2.3 Insight is sudden and perfect

3.2.4 Philosophy of time

3.2.5 Rebirth and Bhavanga

4 Teachings

4.1 Learning

4.1.1 The Three Characteristics

4.1.1.1 Dukkha: The Four Noble Truths

4.1.2 Defilements

4.1.3 Ignorance

4.1.4 Cause and Effect

4.2 Practice

4.2.1 Noble Eightfold Path and Threefold Discipline

4.2.2 Seven purifications

4.2.3 Meditation

4.2.3.1 Samatha meditation

4.3 Attainment

4.3.1 Path and fruit

4.3.2 Levels of attainment

4.3.3 Nirvana

5 Scriptures

5.1 Pali Canon

5.2 Commentaries

6 Lay and monastic life

6.1 Distinction between lay and monastic life

6.2 Monastic vocation

6.3 Ordination

6.4 Monastic practices

6.5 Lay devotee

6.6 Monastic orders within Theravāda

7 Festivals and customs

8 List of Theravāda majority countries

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

11.1 Book references

11.2 Web references

12 Bibliography

13 External links

Adherents

Theravāda Buddhism is followed by countries and people around the globe, and is:

- In South Asia:

- Nepal

Sri Lanka (by 70% of the population)

Bangladesh (by 0.7% of the population) mainly in Chittagong Hill Tracts and Kuwakata,Barishal

India, traditional theravada mainly in Seven Sister States

- In Southeast Asia:

Cambodia (by 95% of the population)

Laos (by 67% of the population)

Myanmar (by 89% of the population)

Thailand (by 90% of the population, 94% of the population that practices religion)

Vietnam (by the Khmer Krom in the south and central parts of Vietnam and Tai Dam in northern Vietnam)

Malaysia (in peninsular Malaysia especially north-western parts of Malaysia, primarily by the Malaysian Siamese and Malaysian Sinhalese)- Indonesia

- Singapore

- In East Asia:

China (mainly by the Shan, Tai, Dai, Hani, Wa, Achang, Blang ethnic groups mainly in Yunnan province )

- Theravāda has also recently gained popularity in the Western world.

Today, Theravāda Buddhists, otherwise known as Theravadins, number over 150 million worldwide, and during the past few decades Theravāda Buddhism has begun to take root in the West[a] and in the Buddhist revival in India.[web 2]

History

Origins

Ashoka and Moggaliputta-Tissa at the Third Council, at the Nava Jetavana, Shravasti

|

| Early Buddhism |

|---|

Scriptures

|

Councils

|

Early Buddhist schools .mw-parser-output .treeview ulpadding:0;margin:0.mw-parser-output .treeview lipadding:0;margin:0;list-style-type:none;list-style-image:none.mw-parser-output .treeview li libackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Treeview-grey-line.png")no-repeat 0 -2981px;padding-left:21px;text-indent:0.3em.mw-parser-output .treeview li li:last-childbackground-position:0 -5971px.mw-parser-output .treeview li.emptyline>ul>.mw-empty-elt:first-child+.emptyline,.mw-parser-output .treeview li.emptyline>ul>li:first-childbackground-position:0 9px

|

The name Theravāda comes[b] from the ancestral Sthāvirīya, one of the early Buddhist schools, from which the Theravadins claim descent. After unsuccessfully trying to modify the Vinaya, a small group of "elderly members", i.e. sthaviras, broke away from the majority Mahāsāṃghika during the Second Buddhist council, giving rise to the Sthavira sect.[5] According to its own accounts, the Theravāda school is fundamentally derived from the Vibhajjavāda "doctrine of analysis" grouping,[6] which was a division of the Sthāvirīya.

According to Damien Keown, there is no historical evidence that the Theravāda school arose until around two centuries after the Great Schism which occurred at the Third Council.[7] Theravadin accounts of its own origins mention that it received the teachings that were agreed upon during the putative Third Buddhist council under the patronage of the Indian Emperor Ashoka around 250 BCE. These teachings were known as the Vibhajjavada.[8] Emperor Ashoka is supposed to have assisted in purifying the sangha by expelling monks who failed to agree to the terms of Third Council.[9] The elder monk Moggaliputta-Tissa was at the head of the Third council and compiled the Kathavatthu ("Points of Controversy"), a refutation of various opposing views which is an important work in the Theravada Abhidhamma.

Later, the Vibhajjavādins in turn is said to have split into four groups: the Mahīśāsaka, Kāśyapīya, Dharmaguptaka, and the Tāmraparṇīya.

Transmission to Sri Lanka

Sanghamitta and the Bodhi Tree

Mihintale, the traditional location of Devanampiya Tissa's conversion

The Theravāda is said to be descended from the Tāmraparṇīya sect, which means "the Sri Lankan lineage". Missionaries sent abroad from India are said to have included Ashoka's son Mahinda (who studied under Moggaliputta-Tissa) and his daughter Sanghamitta, and they were the mythical founders of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, a story which scholars suggest helps to legitimize Theravāda's claims of being the oldest and most authentic school.[9] According to the Mahavamsa chronicle their arrival in Sri Lanka is said to have been during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura (307–267 BCE) who converted to Buddhism and helped build the first Buddhist stupas.

According to S. D. Bandaranayake:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

The rapid spread of Buddhism and the emergence of an extensive organization of the sangha are closely linked with the secular authority of the central state ... There are no known artistic or architectural remains from this epoch except for the cave dwellings of the monks, reflecting the growth and spread of the new religion. The most distinctive features of this phase and virtually the only contemporary historical material, are the numerous Brahmi inscriptions associated with these caves. They record gifts to the sangha, significantly by householders and chiefs rather than by kings. The Buddhist religion itself does not seem to have established undisputed authority until the reigns of Dutthagamani and Vattagamani (ca mid-2nd century BCE to mid-1st century BCE) ...[10]

The first records of Buddha images come from the reign of king Vasabha (65–109 BCE), and after the 3rd century AD the historical record shows a growth of the worship of Buddha images as well as Bodhisattvas.[10]

In the 7th century, the Chinese pilgrim monks Xuanzang and Yijing refer to the Buddhist schools in Sri Lanka as Shàngzuòbù (Chinese: 上座部), corresponding to the Sanskrit Sthavira nikāya and Pali Thera Nikāya.[11]Yijing writes, "In Sri Lanka the Sthavira school alone flourishes; the Mahasanghikas are expelled".[12]

The school has been using the name Theravāda for itself in a written form since at least the 4th century, about one thousand years after the Buddha's death, when the term appears in the Dīpavaṁsa.[13][need quotation to verify]

According to Buddhist scholar A. K. Warder, the Theravāda

spread rapidly south from Avanti into Maharashtra and Andhra and down to the Chola country (Kanchi), as well as Sri Lanka. For some time they maintained themselves in Avanti as well as in their new territories, but gradually they tended to regroup themselves in the south, the Great Vihara (Mahavihara) in Anuradhapura, the ancient capital of Sri Lanka, becoming the main centre of their tradition, Kanchi a secondary center and the northern regions apparently relinquished to other schools.[14]

Between the reigns of Sena I (833–853) and Mahinda IV (956–972), the city of Anuradhapura saw a "colossal building effort" by various kings during a long period of peace and prosperity, the great part of the present architectural remains in this city date from this period.[15]

Pali textual tradition

Buddhaghosa (c. 5th century), the most important Abhidharma scholar of Theravāda Buddhism, presenting three copies of the Visuddhimagga.

The Sri Lankan Buddhist Sangha initially preserved the Buddhist scriptures (the Tipitaka) orally as it had been traditionally done, however during the first century BCE, famine and wars led to the writing down of these scriptures. The Sri Lankan chronicle The Mahavamsa records: "Formerly clever monks preserved the text of the Canon and its commentaries orally, but then, when they saw the disastrous state of living beings, they came together and had it written down in books, that the doctrine might long survive."[16]

According to Richard Gombrich this is "the earliest record we have of Buddhist scriptures being committed to writing anywhere".[16] The Theravada Pali texts which have survived (with only a few exceptions) are derived from the Mahavihara (monastic complex) of Anuradhapura, the ancient Sri Lankan capital.[17]

Later developments included the formation and recording of the Theravada commentary literature (Atthakatha). The Theravada tradition records that even during the early days of Mahinda, there was already a tradition of Indian commentaries on the scriptures.[18] Prior to the writing of the classic Theravada Pali commentaries, there were also various commentaries on the Tipitaka written in the Sinhalese language, such as the Maha-atthakatha ("Great commentary"), the main commentary tradition of the Mahavihara monks.[19]

Of great importance to the commentary tradition is the work of the great Theravada scholastic Buddhaghosa (4th–5th century CE), who is responsible for most of the Theravada commentary literature that has survived (any older commentaries have been lost). Buddhaghosa wrote in Pali, and after him, most Sri Lankan Buddhist scholastics did as well.[20] This allowed the Sri Lankan tradition to become more international through a lingua franca so as to converse with monks in India and later Southeast Asia.

Theravada monks also produced other Pali literature such as historical chronicles (e.g. Mahavamsa), hagiographies, practice manuals, summaries, textbooks, poetry and Abhidhamma works such as the Abhidhammattha-sangaha and the Abhidhammavatara. Buddhaghosa's work on Abhidhamma and Buddhist practice outlined in works such as the Visuddhimagga and the Atthasalini are the most influential texts apart from the Pali Canon texts themselves in the Theravada tradition. Other Theravada Pali commentators and writers include Dhammapala and Buddhadatta. Dhammapala wrote commentaries on the Pali Canon texts which Buddhaghosa had omitted and also wrote a commentary called the Paramathamanjusa on Buddhaghosa's great manual, the Visuddhimagga.

Theravāda subdivisions

Over much of the early history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, three subdivisions of Theravāda existed in Sri Lanka, consisting of the monks of the Mahāvihāra, Abhayagiri vihāra and Jetavana[21], each of which were based in Anuradhapura. The Mahāvihāra was the first tradition to be established, while Abhayagiri Vihāra and Jetavana Vihāra were established by monks who had broken away from the Mahāvihāra tradition.[21] According to A. K. Warder, the Indian Mahīśāsaka sect also established itself in Sri Lanka alongside the Theravāda, into which they were later absorbed.[21] Northern regions of Sri Lanka also seem to have been ceded to sects from India at certain times.[21]

Buddha painting in Dambulla cave temple in Sri Lanka. The Buddhist cave-temple complex was established as a Buddhist Monastery in the 3rd century BCE. Caves were converted into a temple in the 1st century BCE.[22]

When the Chinese monk Faxian visited the island in the early 5th century, he noted 5000 monks at Abhayagiri, 3000 at the Mahāvihāra, and 2000 at the Cetiyapabbatavihāra.[23]

The Mahavihara ("Great Monastery") school became dominant in Sri Lanka at the beginning of the 2nd millennium CE and gradually spread through mainland Southeast Asia. It was established in Myanmar in the late 11th century, in Thailand in the 13th and early 14th centuries, and in Cambodia and Laos by the end of the 14th century. Although Mahavihara never completely replaced other schools in Southeast Asia, it received special favor at most royal courts. This is due to the support it received from local elites, who exerted a very strong religious and social influence.

[24]

Theravada, a group of monks who disagreed with the Mahavihara way, decided to rebel and form their own alliance group. Mahavihara was essential to Theravada, because it was in fact the center of Theravada Buddhism. It was responsible for the development of Sri Lankan people, based off their religious beliefs and acceptable lifestyle. In the religious sense of Theravada, there are no further subdivisions, if Mahavihara does not cease to exist.

[25]

Mahāyāna influences

Over the centuries, the Abhayagiri Theravādins maintained close relations with Indian Buddhists and adopted many new teachings from India.[26] including many elements from Mahāyāna teachings, while the Jetavana Theravādins adopted Mahāyāna to a lesser extent.[23][27]

Xuanzang wrote of two major divisions of Theravāda in Sri Lanka, referring to the Abhayagiri tradition as the "Mahāyāna Sthaviras", and the Mahāvihāra tradition as the "Hīnayāna Sthaviras".[28] Xuanzang further writes:[23]

The Mahāvihāravāsins reject the Mahāyāna and practise the Hīnayāna, while the Abhayagirivihāravāsins study both Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna teachings and propagate the Tripiṭaka.

Akira Hirakawa notes that the surviving Pāli commentaries (Aṭṭhakathā) of the Mahāvihāra school, when examined closely, also include a number of positions that agree with Mahāyāna teachings.[29] Kalupahana notes the same for the Visuddhimagga, the most important Theravāda commentary.[30]

It is known that in the 8th century, both Mahāyāna and the esoteric Vajrayāna form of Buddhism were being practised in Sri Lanka, and two Indian monks responsible for propagating Esoteric Buddhism in China, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, visited the island during this time.[31] Abhayagiri Vihāra appears to have been a center for Theravadin Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna teachings.[32]

Reign of Parakramabahu I

Parakramabahu I commissioned various religious projects such as Gal Vihara ('The Stone Shrine') in Polonnaruwa features three statues of the Buddha in three different poses carved from the same large rock.

Some scholars have held that the rulers of Sri Lanka ensured that Theravāda remained traditional, and that this characteristic contrasts with Indian Buddhism.[33] However, before the 12th century, more rulers of Sri Lanka gave support and patronage to the Abhayagiri Theravādins, and travelers such as Faxian saw the Abhayagiri Theravādins as the main Buddhist tradition in Sri Lanka.[34][35]

The trend of the Abhayagiri Vihara being the dominant sect changed in the 12th century, when the Mahāvihāra sect gained the political support of Parakramabahu I (1153–1186), who completely abolished the Abhayagiri and Jetavanin traditions.[36][37]

The Theravāda monks of these two traditions were then defrocked and given the choice of either returning to the laity permanently, or attempting reordination under the Mahāvihāra tradition as "novices" (sāmaṇera).[37][38]Richard Gombrich writes:[39]

Though the chronicle says that he reunited the Sangha, this expression glosses over the fact that what he did was to abolish the Abhayagiri and Jetavana Nikāyas. He laicized many monks from the Mahā Vihāra Nikāya, all the monks in the other two – and then allowed the better ones among the latter to become novices in the now 'unified' Sangha, into which they would have in due course to be reordained.

Regarding the differences between these three Theravāda traditions, the Cūḷavaṁsa laments, "Despite the vast efforts made in every way by former kings down to the present day, the Bhikkhus turned away in their demeanor from one another and took delight in all kinds of strife."[40]

Parakkamabāhu I rebuilt the ancient cities of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, restoring Buddhist stupas and Viharas (monasteries).[41] He appointed a Sangharaja, or "King of the Sangha", a monk who would preside over the Sangha and its ordinations in Sri Lanka, assisted by two deputies.[39] The reign of Parakkamabāhu also saw a flowering of Theravada scholasticism with the work of prominent Sri Lankan scholars such as Anuruddha, Sāriputta Thera, Mahākassapa Thera of Dimbulagala Vihara and Moggallana Thera.[41] They worked on compiling of subcommentaries on the Tipitaka, texts on grammar, summaries and textbooks on Abhidhamma and Vinaya such as the influential Abhidhammattha-sangaha of Anuruddha.

Lineage of nuns

A few years after the arrival of Mahinda, the bhikkhu Saṅghamittā, who is also believed to have been the daughter of Ashoka, came to Sri Lanka. She ordained the first nuns in Sri Lanka. In 429, by request of China's emperor, nuns from Anuradhapura were sent to China to establish the order there, which subsequently spread across East Asia. The prātimokṣa of the nun's order in East Asian Buddhism is the Dharmaguptaka, which is different than the prātimokṣa of the current Theravada school; the specific ordination of the early Sangha in Sri Lanka not known, although the Dharmaguptaka sect originated with the Sthāvirīya as well.

The nun's order subsequently died out in Sri Lanka in the 11th century and in Burma in the 13th century. It had already died out around the 10th century in other Theravadin areas. Novice ordination has also disappeared in those countries. Therefore, women who wish to live as renunciates in those countries must do so by taking eight or ten precepts. Neither laywomen nor formally ordained, these women do not receive the recognition, education, financial support or status enjoyed by Buddhist men in their countries. These "precept-holders" live in Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Nepal, and Thailand. In particular, the governing council of Burmese Buddhism has ruled that there can be no valid ordination of women in modern times, though some Burmese monks disagree. Japan is a special case as, although it has neither the bhikkhuni nor novice ordinations, the precept-holding nuns who live there do enjoy a higher status and better education than their precept-holder sisters elsewhere, and can even become Zen priests.[42] In Tibet there is currently no bhikkhuni ordination, but the Dalai Lama has authorized followers of the Tibetan tradition to be ordained as nuns in traditions that have such ordination.

In 1996, 11 selected Sri Lankan women were ordained fully as Theravada bhikkhunis by a team of Theravāda monks in concert with a team of Korean nuns in India. There is disagreement among Theravāda vinaya authorities as to whether such ordinations are valid. The Dambulla chapter of the Siam Nikaya in Sri Lanka also carried out a nun's ordination at this time, specifically stating their ordination process was a valid Theravadin process where the other ordination session was not.[43] This chapter has carried out ordination ceremonies for hundreds of nuns since then.[citation needed] This has been criticized by leading figures in the Siam Nikaya and Amarapura Nikaya, and the governing council of Buddhism in Myanmar has declared that there can be no valid ordination of nuns in modern times, though some Burmese monks disagree with this.[44]

In 1997 Dhamma Cetiya Vihara in Boston was founded by Ven. Gotami of Thailand, then a 10 precept nun; when she received full ordination in 2000, her dwelling became America's first Theravada Buddhist bhikkhuni vihara.

A 55-year-old Thai Buddhist 8-precept white-robed maechee nun, Varanggana Vanavichayen, became the first woman to receive the going-forth ceremony of a Theravada novice (and the gold robe) in Thailand, in 2002.[45] On February 28, 2003, Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, formerly known as Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, became the first Thai woman to receive bhikkhuni ordination as a Theravada nun.[46]

Dhammananda Bhikkhuni was ordained in Sri Lanka.[47] The Thai Senate has reviewed and revoked the secular law passed in 1928 banning women's full ordination in Buddhism as unconstitutional for being counter to laws protecting freedom of religion. However Thailand's two main Theravada Buddhist orders, the Mahanikaya and Dhammayutika Nikaya, have yet to officially accept fully ordained women into their ranks.

In 2009 in Australia four women received bhikkhuni ordination as Theravada nuns, the first time such ordination had occurred in Australia.[48] It was performed in Perth, Australia, on 22 October 2009 at Bodhinyana Monastery. Abbess Vayama together with Venerables Nirodha, Seri, and Hasapanna were ordained as Bhikkhunis by a dual Sangha act of Bhikkhus and Bhikkhunis in full accordance with the Pali Vinaya.[49]

In 2010, in the US, four novice nuns were given the full bhikkhuni ordination in the Thai Theravada tradition, which included the double ordination ceremony. Henepola Gunaratana and other monks and nuns were in attendance. It was the first such ordination ever in the Western hemisphere.[50]

The first bhikkhuni ordination in Germany, the ordination of German woman Samaneri Dhira, occurred on June 21, 2015 at Anenja Vihara.[51]

In Indonesia, the first Theravada ordination of bhikkhunis in Indonesia after more than a thousand years occurred in 2015 at Wisma Kusalayani in Lembang, Bandung in West Java.[52] Those ordained included Vajiradevi Sadhika Bhikkhuni from Indonesia, Medha Bhikkhuni from Sri Lanka, Anula Bhikkhuni from Japan, Santasukha Santamana Bhikkhuni from Vietnam, Sukhi Bhikkhuni and Sumangala Bhikkhuni from Malaysia, and Jenti Bhikkhuni from Australia.[52]

Spread to Southeast Asia

Bawbawgyi Pagoda at Sri Ksetra, prototype of Pagan-era pagodas

According to the Mahavamsa, a Sri Lankan chronicle, after the conclusion of the Third Buddhist council, a mission was sent to Suvarnabhumi, led by two monks, Sona and Uttara.[53] Scholarly opinions differ as to where exactly this land of Suvarnabhumi was located, but it is generally believed to have been located somewhere in the area of Lower Burma, Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, or Sumatra.

Before the 12th century, the areas of Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia were dominated by Buddhist sects from India, and included the teachings of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[54][55] In the 7th century, Yijing noted in his travels that in these areas, all major sects of Indian Buddhism flourished.[54]

Though there are some early accounts that have been interpreted as Theravāda in Myanmar, the surviving records show that most Burmese Buddhism incorporated Mahāyāna, and used Sanskrit rather than Pali.[55][56][57] After the decline of Buddhism in India, missions of monks from Sri Lanka gradually converted Burmese Buddhism to Theravāda, and in the next two centuries also brought Theravāda Buddhism to the areas of Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, where it supplanted previous forms of Buddhism.[58]

The Mon and Pyu were among the earliest people to inhabit Myanmar. The oldest surviving Buddhist texts in the Pali language come from Pyu city-state of Sri Ksetra, the text which is dated from the mid 5th to mid 6th century is written on twenty-leaf manuscript of solid gold.[59] According to Peter Skilling:

"From the point of view of both language and contents, I conclude that the Pali inscriptions of Burma and Siam give firm evidence for a Theravadin presence in the Irrawaddy and Chao Phraya basins, from about the 5th century CE onwards. From the extent and richness of the evidence it seems that the Theravada was the predominant school, and that it enjoyed the patronage of ruling and economic elites. But I do not mean to suggest that religious society was monolithic: other schools may well have been present, or have come and gone, and there is ample evidence

for the practice of Mahayana and Brahmanism in the region."[60][full citation needed]

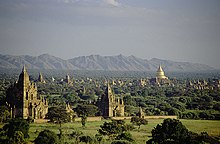

Ruins of Bagan, an ancient capital of Myanmar. There are more than 2,000 kyaung there. During the height of Bagan's power, there were some 13,000 kyaung.[web 3]

The Burmese slowly became Theravādan as they came into contact and conquered the Pyu and Mon civilizations. This began in the 11th century during the reign of the Bamar king Anawrahta (1044–1077) of the Pagan Kingdom who acquired the Pali scriptures in a war against the Mon as well as from Sri Lanka and build stupas and monasteries at his capital of Bagan.[61] Various invasions of Burma by neighboring states and the Mongol invasions of Burma (13th century) damaged the Burmese sangha and Theravada had to be reintroduced several times into the country from Sri Lanka and Thailand.

The Khmer Empire (802–1431) centered in Cambodia was initially dominated by Hinduism; Hindu ceremonies and rituals were performed by Brahmins, usually only held among ruling elites of the king's family, nobles, and the ruling class. Tantric Mahayana Buddhism was also a prominent faith, promoted by Buddhist emperors such as Jayavarman VII (1181–1215) who rejected the Hindu gods and presented himself as a Bodhisattva King.

Stairway to Wat Phnom guarded by Nagas, the oldest Buddhist structure at the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh.

King Jayavarman VII (reigned c. 1181–1218) had sent his son Tamalinda to Sri Lanka to be ordained as a Buddhist monk and study Theravada Buddhism according to the Pali scriptural traditions in the Mahavihara monastery. Tamalinda then returned to Cambodia and promoted Buddhist traditions according to the Theravada training he had received, galvanizing and energizing the long-standing Theravada presence that had existed throughout the Angkor empire for centuries. During the 13th and 14th centuries, Theravada monks from Sri Lanka continued introducing orthodox Theravada Buddhism which eventually became the dominant faith among all classes.[62] The monasteries replaced the local priestly classes, becoming centers of religion, education, culture and social service for Cambodian villages. This led to high levels of literacy among Cambodians.[63]

Sukhothai Historical Park, Thailand.

In Thailand, Theravada existed alongside Mahayana and other religious sects before the rise of Sukhothai Kingdom.[64] During the reign of King Ram Khamhaeng (c. 1237/1247 – 1298) Theravada was made the main state religion and promoted by the king.

During the pre-modern era, Southeast Asian Buddhism included numerous elements which could be called tantric and esoteric (such as the use of mantras and yantras in elaborate rituals). The French scholar François Bizot has called this "Tantric Theravada", and his textual studies show that it was a major tradition in Cambodia and Thailand.[65] Some of these practices are still prevalent in Cambodia and Laos today.

Despite its success in Southeast Asia, Theravāda Buddhism in China has generally been limited to areas bordering Theravāda countries.

Late innovations and esotericism

Later Theravada textual materials show new and somewhat unorthodox developments in theory and practice. These developments include what has been called the "Yogāvacara tradition" associated with the Sinhalese Yogāvacara's manual (c. 16th to 17th centuries) and also Esoteric Theravada also known as Borān kammaṭṭhāna ('ancient practices'). These traditions include new practices and ideas which are not included in classical orthodox Theravada works like the Visuddhimagga, such as the use of mantras (such as Araham), the practice of magical formulas, complex rituals and complex visualization exercises.[66][67] These practices were particularly prominent in the Siam Nikaya before the modernist reforms of King Rama IV (1851–1868) as well as in Sri Lanka.

Modernisation and spread to the West

Henry Olcott and Buddhists (Colombo, 1883).

In the 19th century began a process of mutual influence of both Asian Theravadins and a Western audience interested in ancient wisdom. Especially Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott, founders of the Theosophical Society had a profound role in this process. In Theravāda countries a lay vipassana practice developed. From the 1970s on, Western interest gave way to the growth of the Vipassana movement in the West.[68]

Reaction against Western colonialism

Buddhist revivalism has also reacted against changes in Buddhism caused by colonialist regimes. Western colonialists and Christian missionaries deliberately imposed a particular type of Christian monasticism on Buddhist clergy in Sri Lanka and colonies in Southeast Asia, restricting monks' activities to individual purification and temple ministries.[69] Prior to British colonial control, monks in both Sri Lanka and Burma had been responsible for the education of the children of lay people, and had produced large bodies of literature. After the British takeover, Buddhist temples were strictly administered and were only permitted to use their funds on strictly religious activities. Christian ministers were given control of the education system and their pay became state funding for missions.[70]

Foreign, especially British, rule had an enervating effect on the sangha.[71] According to Walpola Rahula, Christian missionaries displaced and appropriated the educational, social, and welfare activities of the monks, and inculcated a permanent shift in views regarding the proper position of monks in society through their institutional influence upon the elite.[71] Many monks in post-colonial times have dedicated themselves to undoing these changes.[72] Movements intending to restore Buddhism's place in society have developed in both Sri Lanka and Myanmar.[73]

One consequence of the reaction against Western colonialism has been a modernization of Theravāda Buddhism: Western elements have been incorporated, and meditation practice has opened to a lay audience. Modernized forms of Theravādan practice have spread to the West.[68]

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Avukana Buddha statue, 5th century

In Sri Lanka Theravadins were looking at Western culture to find means to revitalize their own tradition. Christian missionaries were threatening the indigenous culture.[74] As a reaction to this, Theravadins started to propagate Theravāda Buddhism. They were aided by the Theosophical Society, who were dedicated to the search for wisdom within ancient sources, including Buddhism and the Pāli Canon. Anagarika Dharmapala was one of the Theravāda leaders with whom the Theosophists sided. Dharmapala tried to reinstate vipassanā, using the Visuddhimagga and the Pali Canon as a foundation. Dharmapala reached out to the middle classes, offering them religious practice and a religious identity, which were used to withstand the British imperialists. As a result of Dharmapapla's efforts lay practitioners started to practise meditation, which had been reserved specifically for the monks.[75]

The translation and publication of the Pāli Canon by the Pali Text Society made the Pali Canon better available to a lay audience, not only in the West, but also in the East. Western lay interest in Theravāda Buddhism was promoted by the Theosophical Society, and endured until the beginning of the 20th century. During the 1970s interest rose again, leading to a surge of Westerners searching for enlightenment, and the republishing of the Pāli Canon, first in print, and later on the internet.

Thailand

The Great Buddha of Thailand in the Wat Muang Monastery in Ang Thong Province is the tallest statue in Thailand, and the ninth tallest in the world.

With the coming to power in 1851 of King Mongkut, who had been a monk himself for twenty-seven years, the sangha, like the kingdom, became steadily more centralized and hierarchical, and its links to the state more institutionalized. Mongkut was a distinguished scholar of Pali Buddhist scripture. Moreover, at that time the immigration of numbers of monks from Burma was introducing the more rigorous discipline characteristic of the Mon sangha. Influenced by the Mon and guided by his own understanding of the Tipitaka, Mongkut began a reform movement that later became the basis for the Dhammayuttika Nikaya.

In the early 1900s, Thailand's Ajahn Sao Kantasīlo and his student, Mun Bhuridatta, led the Thai Forest Tradition revival movement. In the 20th century notable practitioners included Ajahn Thate, Ajahn Maha Bua and Ajahn Chah.[76] It was later spread globally by Ajahn Mun's students including Ajahn Thate, Ajahn Maha Bua and Ajahn Chah and several Western disciples, among whom the most senior is Luang Por Ajahn Sumedho.

Myanmar

Laykyun Sekkya in the village of Khatakan Taung near Monywa, Myanmar. It is the second tallest statue in the world.

Burmese Theravāda Buddhism has had a profound influence on modern vipassanā practice, both for lay practitioners in Asia as in the West.

The "New Burmese method" was developed by U Nārada and popularized by his student Mahasi Sayadaw and Nyanaponika Thera. Another prominent teacher is Bhikkhu Bodhi, a student of Nyanaponika. The New Burmese Method strongly emphasizes vipassanā over samatha. It is regarded as a simplification of traditional Buddhist meditation techniques, suitable not only for monks but also for lay practitioners. The method has been popularized in the West by teachers as Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, Tara Brach, Gil Fronsdal and Sharon Salzberg.

The Ledi lineage begins with Ledi Sayadaw.[77]S. N. Goenka is a well-known teacher in the Ledi-lineage. According to S. N. Goenka, vipassana techniques are essentially nonsectarian in character, and have universal application. Meditation centers teaching the vipassanā popularized by S. N. Goenka exist now in India, Asia, North and South America, Europe, Australia, Middle East and Africa.[78]

Modern developments

The following modern trends or movements have been identified.[79][web 4]

- Modernism: attempts to adapt to the modern world and adopt some of its ideas; including, among other things:

- Green movement

Syncretism with other Buddhist as well as Hindu (in Sri Lanka, India, Nepal, Bali and Thailand) traditions- Universal inclusivity

- Reformism: attempts to restore a supposed earlier, ideal state of Buddhism; includes in particular the adoption of Western scholars' theories of original Buddhism (in recent times the "Western scholarly interpretation of Buddhism" is the official Buddhism prevailing in Sri Lanka and Thailand).[80]

- Ultimatism: tendency to concentrate on advanced teachings such as the Four Noble Truths at the expense of more elementary ones

- Neotraditionalism; includes among other things

- Revival of ritualism

- Remythologization

A man meditates in Myanmar

Vipassanā (Insight meditation)- Social action

- Devotional religiosity

- Reaction to Buddhist nationalism

- Renewal of forest monks

- Revival of samatha meditation

- Revival of the Theravāda bhikkhuni (female monastic) lineage (not recognized by some male sangha authorities)

Doctrine

The Buddha preaches Abhidhamma to his Mother in Heaven, Chedi Traiphop Traimongkhon Temple, Hatyai

The Vibhajjavāda school (‘the analysts’), the branch of the Sthāvira school from which Theravāda is derived, differed from other early Buddhist schools on a variety of teachings.[81] The differences resulted from the systemization of the Buddhist teachings, which was preserved in the abhidharmas of the various schools.[82] The doctrinal positions of the Theravāda school is expounded in various texts known as Abhidhamma as well as the Pali commentaries (Atthakatha) and post-canonical works like the Visuddhimagga.

The Abhidhamma is "a restatement of the doctrine of the Buddha in strictly formalised language ... assumed to constitute a consistent system of philosophy".[83] Its aim is not the empirical verification of the Buddhist teachings,[83] but "to set forth the correct interpretation of the Buddha's statements in the Sutra to restate his 'system' with perfect accuracy".[83]

The Theravāda school has traditionally held the doctrinal position that the canonical Abhidhamma Pitaka was actually taught by the Buddha himself.[84] Modern scholarship in contrast, has generally held that the Abhidhamma texts date from the 3rd century BCE.[85]

Dhamma theory

The central theory of the Abhidhamma is what is known as the "Dhamma theory".[86] According to Y. Karunadasa, a dhamma, which can be translated as "a 'principle' or 'element' (dharma)", is "those items that result when the process of analysis is taken to its ultimate limits".[86] "Dhamma" has been translated as "factors" (Collett Cox), "psychic characteristics" (Bronkhorst), "psycho-physical events" (Noa Ronkin) and "phenomena" (Nyanaponika Thera).[87][88]

Dhammas are defined by Theravāda commentaries as:[89]

[D]harmas are what have (or 'hold', 'maintain', dhr is the nearest equivalent in the language to the English 'have') their own own-being (sabhāva). It is added that they naturally (yathasvabhavatas) have this through conditions (pratyaya). The idea is that they are distinct, definable, principles in the constitution of the universe."[90]

However, dhammas are not individual, discrete and separate entities, they are always in dependently conditioned relationships with other dhammas and always changing, arising and vanishing. It is thus only for the sake of description that they are said to have their "own nature" (sabhāva).[91] According to Peter Harvey, the Theravāda view of dhammas is that:

"'They are dhammas because they uphold their own nature [sabhāva]. They are dhammas because they are upheld by conditions or they are upheld according to their own nature' (Asl.39). Here 'own-nature' would mean characteristic nature, which is not something inherent in a dhamma as a separate ultimate reality, but arise due to the supporting conditions both of other dhammas and previous occurrences of that dhamma."[92]

Thus, dhammas are not essences or independently existent particulars in Theravāda. In the Visuddhimagga, the Theravāda scholar Buddhaghosa states:

"when they are seen after resolving them by means of knowledge into these elements, they disintegrate like froth subjected to compression by the hand. They are mere states (dhamma) occurring due to conditions and void. In this way the characteristic of not-self becomes more evident" (Vism-mhþ 824).

Doctrinal differences with other Buddhist schools

The doctrinal stances of the Theravāda school vis-a-vis other early Buddhist schools is presented in the Pali text known as the Kathāvatthu, "Points of Controversy", which said to have been compiled by the scholar Moggaliputta-Tissa (ca. 327 – 247 BCE). It includes several philosophical and soteriological matters, including the following.

View of the Arhat

Theravadins believe that an awakened arahant (lit. worthy one) has an "incorruptible nature", unlike other early Buddhist schools like the Mahāsāṃghika who believed arahants could regress.[93] Theravadins also dispute the idea that an arahant may be lacking in knowledge, or have doubts, or that they could have nocturnal emissions and thus still have some residual fetter of sensuality.[94] They also argued against the Uttarapathaka school's view that a layperson could become an arahant and continue to live the household life.[94]

View of the Buddha

The Theravāda school rejected the view of the Lokottaravada schools which held that even the Buddha's conventional speech was supramundane or transcendental.[95] They also rejected the proto-Mahayana docetic view of the Vetulyaka school that the Buddha himself did not teach the Dharma, but that it was taught by his magical creation or "phantom" while he himself remained in Tavatimsa Heaven.[96]

Insight is sudden and perfect

According to the Theravāda, "progress in understanding comes all at once, 'insight' (abhisamaya) does not come 'gradually' (successively – anapurva)", a belief known as subitism.[97] This is reflected in the Theravāda account on the four stages of enlightenment, in which the attainment of the four paths appears suddenly and the defilements are rooted out at once. The same stance is taken in the contemporary vipassana movement, especially the "New Burmese Method".[citation needed]

Philosophy of time

On the Philosophy of time, the Theravāda tradition holds to philosophical presentism, the view that only present moment dhammas exist, against the eternalist view of the Sarvāstivādin tradition which held that dhammas exist in all three times - past, present, future.[98]

The early Theravadins who compiled the Kathāvatthu also rejected the doctrine of momentariness (Skt., kṣāṇavāda, Pali, khāṇavāda) upheld by other Buddhist Abhidharma schools like the Sarvastivada, which held that all dhammas lasted for a "moment" which for them meant an atomistic unit of time, that is the shortest possible slice of time.[99] According to Noa Ronkin, the Theravadins meanwhile, used the term "moment" (khāṇa) as a simple expression for a "short while", "the dimension of which is not fixed but may be determined by the context".[99] In the Khanikakatha of the Kathavatthu, the Theravadins also argue that "only mental phenomena are momentary, whereas material phenomena endure for a stretch of time".[99]

Rebirth and Bhavanga

Regarding the mechanisms of rebirth, orthodox Theravadins following the Kathavatthu, rejected the doctrine of the intermediate state (antarabhāva) between death and rebirth, holding instead that rebirth is immediate.[100] However, recently some Theravada monks have written in favor of the idea, such as Ven. Balangoda Ananda Maitreya. [101]

The doctrine of the Bhavanga ("ground of becoming", "condition for existence") is an innovation of the Theravāda Abhidhamma, where it is a passive mode of consciousness (citta). According to Rupert Gethin, it is "the state in which the mind is said to rest when no active consciousness process is occurring", such as in deep dreamless sleep.[102] It is also said to be a process which conditions the future rebirth consciousness.[103]

Teachings

Painting of Buddha's first sermon from Wat Chedi Liem in Thailand

Theravāda promotes the concept of vibhajjavāda "teaching of analysis". This doctrine says that insight must come from the aspirant's experience, application of knowledge, and critical reasoning. However, the scriptures of the Theravadin tradition also emphasize heeding the advice of the wise, considering such advice and evaluation of one's own experiences to be the two tests by which practices should be judged.

Theravāda orthodoxy takes the seven stages of purification as its basic outline of the path to be followed.

The Theravāda Path starts with learning, to be followed by practise, culminating in the realization of Nirvana.[c]

Learning

The Three Characteristics

Wat Chaiwatthanaram in Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Thailand

Throughout the Pali Canon, two characteristics of all saṅkhāra (conditioned phenomena) and one characteristic of all dhammas are mentioned. The Theravāda tradition has grouped them together. Insight into these three characteristics is the entry to the Buddhist path:

Anicca (impermanence): All conditioned phenomena are subject to change, including physical characteristics, qualities, assumptions, theories, knowledge, etc. Nothing is permanent, because, for something to be permanent, there has to be an unchanging cause behind it. Since all causes are recursively bound together, there can be no ultimate unchanging cause.

Dukkha (suffering): Craving causes suffering, since what is craved is transitory, changing, and perishing. The craving for impermanent things causes disappointment and sorrow. There is a tendency to label practically everything in the world, as either "good", "comfortable" or "satisfying"; or "bad", "uncomfortable", and "unsatisfying". Labeling things in terms of like and dislike creates suffering. If one succeeds in giving up the tendency to label things, and freeing themself from the instincts that drive them towards attaining what they themselves label collectively as "liking", they attain the ultimate freedom. The problem, the cause, the solution and the implementation, all of these are within oneself, not outside.

Anatta (not-self): all dhammas lack a fixed, unchanging 'essence'; there is no permanent, essential ātta (self). A living being is a composite of the five aggregates (khandhas), which are the physical forms (rupa), feelings or sensations (vedana), perception (sanna), mental formations (sankhara), and consciousness (vinnana), none of which can be identified as one's Self. From the moment of conception, all entities (including all living beings) are subject to a process of continuous change. A practitioner should, on the other hand, develop and refine their mind to a state so as to see through this phenomenon. Truly understanding this counter-intuitive concept of Buddhism requires direct and personal experience. This is given in vipassanā practice, closely watching the continuous changes in the Five Aggregates.[105]

Dukkha: The Four Noble Truths

The Four Noble Truths are described as follows:

Dukkha (suffering): This can be somewhat broadly classified into three categories. Inherent suffering, or the suffering one undergoes in all the worldly activities, what one suffers in day-to-day life: birth, aging, diseases, death, sadness and so on. In short, all that one feels, from separating from "loving" attachments, and/or associating with "hating" attachments, is encompassed into the term. The second class of suffering, called Suffering due to Change, implies that things suffer because of attaching themselves to a momentary state which is held to be "good"; when that state is changed, things are subjected to suffering. The third, termed Sankhara Dukkha, is the subtlest. Beings suffer simply by not realizing that they are mere aggregates with no definite, unchanging identity.

Dukkha Samudaya (cause of suffering): Craving, which leads to Attachment and Bondage, is the cause of suffering. Formally, this is termed Tanha. It can be classified into three instinctive drives. Kama Tanha is the Craving for any pleasurable sense object (which involves sight, sound, touch, taste, smell and mental perceptives). Bhava Tanha is the Craving for attachment to an ongoing process, which appears in various forms, including the longing for existence. Vibhava Tanha is the Craving for detachment from a process, which includes non-existence and causes the longing for self-annihilation.

Dukkha Nirodha (cessation of suffering): One cannot possibly adjust the whole world to one's taste in order to eliminate suffering and hope that it will remain so forever. This would violate the chief principle of Change. Instead, one adjusts one's own mind through detachment so that the Change, of whatever nature, has no effect on one's peace of mind. Briefly stated, the third Noble Truth implies that elimination of the cause (craving) eliminates the result (suffering). This is implied by the scriptural quote by The Buddha, "Whatever may result from a cause, shall be eliminated by the elimination of the cause".

Dukkha Nirodha Gamini Patipada (pathway to freedom from suffering): This is the Noble Eightfold Pathway towards freedom or Nirvana. The path can roughly be rendered into English as right view, right intention, right speech, right actions, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration.

Defilements

In Theravāda, the cause of human existence and suffering (dukkha) is identified as taṇhā (craving), which carries with it the kilesas (defilements). Those defilements that bind humans to the cycle of rebirth are classified into a set of ten fetters, while those defilements – sometimes referred to in English as "toxic mental states" – that impede samadhi (concentration) are presented in a fivefold set called the five hindrances.[web 5] The level of defilement can be coarse, medium, and subtle. It is a phenomenon that frequently arises, remains temporarily and then vanishes. Theravadins believe defilements are not only harmful to oneself, but also harmful to others. They are the driving force behind all inhumanities a human being can commit.

There are three stages of defilements. During the stage of passivity the defilements lie dormant at the base of the mental continuum as latent tendencies (anusaya), but through the impact of sensory stimulus, they will manifest (pariyutthana) themselves at the surface of consciousness in the form of unwholesome thoughts, emotions, and volitions. If they gather additional strength, the defilements will reach the dangerous stage of transgression (vitikkama), which will then involve physical or vocal actions.

Ignorance

Theravadins believe these defilements are habits born out of avijjā (ignorance) that afflict the minds of all unenlightened beings, who cling to them and their influence in their ignorance of the truth. But in reality, those mental defilements are nothing more than taints that have afflicted the mind, creating suffering and stress. Unenlightened beings cling to the body, under the assumption that it represents a Self, whereas in reality the body is an impermanent phenomenon formed from the mahābhūta. Often characterized by earth, water, fire and air, in the early Buddhist texts these are defined to be abstractions representing the sensorial qualities solidity, fluidity, temperature, and mobility, respectively.[d]

The mental defilements' frequent instigation and manipulation of the mind is believed to have prevented the mind from seeing the true nature of reality. Unskillful behavior in turn can strengthen the defilements, but following the Noble Eightfold Path can weaken or eradicate them. Avijjā is destroyed by insight.

Cause and Effect

The concept of cause and effect, or causality, is a key concept in Theravāda, and indeed, in Buddhism as a whole. This concept is expressed in several ways, including the Four Noble Truths, and most importantly, paticcasamuppāda (dependent co-arising).

Abhidharma in the Pali Canon differentiates between a root cause (hetu) and facilitating cause (pacca). By the combined interaction of both these, an effect is brought about. On top of this view, a logic is built and elaborated whose most supple form can be seen in paticcasamuppāda.

This concept is then used to question the nature of suffering and to elucidate the way out of it, as expressed in the Four Noble Truths. It is also employed in several suttas to refute several philosophies, or any belief system that takes a fixed mindset, or absolute beliefs about the nature of reality.

By taking away a cause, the result will also disappear. From this follows the Buddhist path to end suffering and existence in samsara.

Practice

Theravāda orthodoxy takes the seven stages of purification as the basic outline of the path to be followed. This basic outline is based on the threefold discipline of sīla (ethics or discipline), samādhi (meditative concentration) and paññā (understanding or wisdom). The emphasis is on understanding the three marks of existence, which removes ignorance. Understanding destroys the ten fetters and leads to nibbana.

Theravadins believe that every individual is personally responsible for their own self-awakening and liberation, as they are the ones that were responsible for their own kamma (actions and consequences). Great emphasis is placed upon applying the knowledge through direct experience and personal realization, than believing about the known information about the nature of reality as said by the Buddha.

Noble Eightfold Path and Threefold Discipline

In the Sutta Pitaka, the path to liberation is described by the Noble Eightfold Path:

The Blessed One said, "Now what, monks, is the Noble Eightfold Path? Right view, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration."[web 7]

The Noble Eightfold Path can also be summarized as the Three Noble Disciplines.[web 8][106] These are sīla, paññā, and samādhi.[web 9]

Seven purifications

The Visuddhimagga, written in the fifth century by Buddhaghosa, has become the orthodox account of the Theravāda path to liberation. It gives a sequence of seven purifications, based on the sequence of sīla, samādhi and paññā.

It is composed of three sections, which discuss sīla, samādhi and pañña.

- The first section (part 1) explains the rules of discipline, and the method for finding a correct temple to practise, or how to meet a good teacher.

- The second section (part 2) describes samatha practice, object by object (see kammaṭṭhāna for the list of the forty traditional objects). It mentions different stages of concentration.

- The third section (parts 3–7) is a description of the five khandhas, ayatanas, the Four Noble Truths, paticcasamuppāda, and the practise of vipassanā through the development of wisdom. It emphasizes different forms of knowledge emerging because of the practice. This part shows a great analytical effort specific to Buddhist philosophy.

The seven purifications are:[107]

- Purification of Conduct (sīla-visuddhi)

- Purification of Mind (citta-visuddhi)

- Purification of View (ditthi-visuddhi)

- Purification by Overcoming Doubt (kankha-vitarana-visuddhi)

- Purification by Knowledge and Vision of What Is Path and Not Path (maggamagga-ñanadassana-visuddhi)

- Purification by Knowledge and Vision of the Course of Practice (patipada-ñanadassana-visuddhi)

- Knowledge of contemplation of rise and fall (udayabbayanupassana-nana)

- Knowledge of contemplation of dissolution (bhanganupassana-nana)

- Knowledge of appearance as terror (bhayatupatthana-nana)

- Knowledge of contemplation of danger (adinavanupassana-nana)

- Knowledge of contemplation of dispassion (nibbidanupassana-nana)

- Knowledge of desire for deliverance (muncitukamyata-nana)

- Knowledge of contemplation of reflection (patisankhanupassana-nana)

- Knowledge of equanimity about formations (sankharupekka-nana)

- Conformity knowledge (anuloma-nana)

- Purification by Knowledge and Vision (ñanadassana-visuddhi)

- Change of lineage

- Sotāpanna

- Sakadagami

- Anāgāmi

- Arhat

The "Purification by Knowledge and Vision" is the culmination of the practice, in four stages leading to liberation and Nirvana.

The emphasis in this system is on understanding the three marks of existence, dukkha, anatta and anicca. This emphasis is recognizable in the value that is given to vipassanā over samatha, especially in the contemporary Vipassana movement.

Meditation

Theravādin monks and laymen meditating in Bodh Gaya (Bihar, India)

Theravāda Buddhist meditation practices fall into two broad categories: Samatha and Vipassanā.[web 10] This distinction is not made in the sutras, but in the Visuddhimagga.[web 11]

Meditation (Pali: Bhavana) means the positive reinforcement of one's mind. Meditation is the key tool implemented in attaining Jhāna. Samatha means "to make skillful", and has other renderings, among which are "tranquilizing, calming", "visualizing", and "achieving". Vipassanā means "insight" or "abstract understanding". In this context, Samatha Meditation makes a person skillful in concentration of mind. Once the mind is sufficiently concentrated, vipassanā allows one to see through the veil of ignorance.

In order to be free from suffering and stress, Theravadins believe that the defilements need to be permanently uprooted. Initially the defilements are restrained through mindfulness to prevent them from taking over mental and bodily action. They are then uprooted through internal investigation, analysis, experience and understanding of their true nature by using jhāna. This process needs to be repeated for each and every defilement. The practice will then lead the meditator to realize Nirvana.

Samatha meditation

Thai Forest Tradition meditation master Ajahn Chah with his resident sangha at Wat Nong Pah Pong in Ubon Ratchathani (Thailand)

Samatha meditation in Theravāda is usually involved with the concepts of kammaṭṭhāna, which literally stands for "place of work"; in this context, it is the "place" or object of concentration (Pāli: Ārammana) where the mind is at work. In samatha meditation, the mind is set at work concentrated on one particular entity. There are forty (40) such classic objects (entities) used in samatha meditation, which are termed kammaṭṭhāna. By acquiring a kammaṭṭhāna and practising samatha meditation, one would be able to attain certain elevated states of awareness and skill of the mind called Jhana. Practising samatha has samadhi as its ultimate goal.

It should be noted that samatha is not a method that is unique to Buddhism. In the suttas it is said to be implemented in other contemporary religions in India at the time of Buddha. In fact, the first teachers of Siddhartha, before they attained the state of awakening (Pāli: Bodhi), are said to have been quite skillful in samatha (although the term had not been coined yet). In the Pali Canon, the Buddha frequently instructs his disciples to practise samadhi in order to establish and develop jhāna. Jhāna is the instrument used by the Buddha himself to penetrate the true nature of phenomena (through investigation and direct experience) and to reach Enlightenment.[web 12] Right Concentration (samma-samadhi) is one of the elements in the Noble Eightfold Path. Samadhi can be developed from mindfulness developed with kammaṭṭhāna such as concentration on breathing (anapanasati), from visual objects (kasina), and repetition of phrases. The traditional list contains 40 objects of meditation (kammaṭṭhāna) to be used for Samatha Meditation. Every object has a specific goal; for example, meditation on the parts of the body (kayanupassana or kayagathasathi) will result in a lessening of attachment to our own bodies and those of others, resulting in a reduction of sensual desires. Mettā generates the feelings of goodwill and sukha (happiness) toward ourselves and other beings; mettā practice serves as an antidote to ill-will, wrath and fear.

Attainment

Path and fruit

Practice leads to mundane and supramundane wisdom, leading to Nirvana:

The term "supramundane" [lokuttara] applies exclusively to that which transcends the world, that is the nine supramundane states: Nibbana, the four noble paths (magga) leading to Nibbana, and their corresponding fruits (phala) which experience the bliss of Nibbana.[web 11]

Mundane wisdom is the insight in the three marks of existence.[web 11] The development of this insight leads to four supramundane paths and fruits:

Each path is a momentary peak experience directly apprehending Nibbana and permanently cutting off certain defilements.[web 11]

Each path is followed by its supramundane fruit:

whereas the path performs the active function of cutting off defilements, fruition simply enjoys the bliss and peace that result when the path has completed its task. Also, where the path is limited to a single moment of consciousness, the fruition that follows immediately on the path endures for two or three moments. And while each of the four paths occurs only once and can never be repeated, fruition remains accessible to the noble disciple.[web 11]

Levels of attainment

Four levels of supramundane[web 11] wisdom can be attained:[web 13]

Stream-Enterers: Those who have destroyed the first three fetters (false view of Self, doubt, and clinging to rites and rituals);[web 14][web 15]

Once-Returners: Those who have destroyed the first three fetters and have lessened the fetters of lust and hatred;

Non-Returners: Those who have destroyed the five lower fetters, which bind beings to the world of the senses;[108]

Arahants: Those who have reached Enlightenment—realized Nirvana, and have reached the quality of deathlessness—are free from all the fermentations of defilement. Their ignorance, craving and attachments have ended.[108]

Nirvana

Nirvana (Sanskrit: निर्वाण, Nirvāṇa; Pali: निब्बान, Nibbāna; Thai: นิพพาน, Nípphaan) is the ultimate goal of Theravadins. It is a state where the fire of the passions has been 'blown out', and the person is liberated from the repeated cycle of birth, illness, aging and death. In the Saṃyojanapuggala Sutta of the Aṅgutarra Nikaya, the Buddha describes four kinds of persons and tells us that the last person – the Arahant – has attained Nibbana by removing all 10 fetters that bind beings to samsara:

In the Arahant. In this person, monks, all of the fetters ['saṃyojanāni'] are gotten rid of that pertain to this world, give rise to rebirth, and give rise to becoming.[109]

According to the early scriptures, the Nirvana attained by Arahants is identical to that attained by the Buddha himself, as there is only one type of Nirvana.[web 16] Theravadins believe the Buddha was superior to Arahants because the Buddha discovered the path all by himself and taught it to others (i.e., metaphorically turning the wheel of Dhamma). Arahants, on the other hand, attained Nirvana partly because of the Buddha's teachings. Theravadins revere the Buddha as a supremely gifted person but also recognize the existence of other such Buddhas in the distant past and future. Maitreya (Pali: Metteyya), for example, is mentioned very briefly in the Pali Canon as a Buddha who will come in the distant future.

Scriptures

Pali Canon

One of the 729 large marble tablets of the Pali Canon (the world's largest book) inscribed using the Burmese alphabet at the Kuthodaw Pagoda in Mandalay, Myanmar.

The Theravāda school upholds the Pali Canon or Tipitaka as the most authoritative collection of texts on the teachings of Gautama Buddha. The Sutta and Vinaya portion of the Tipitaka shows considerable overlap in content to the Agamas, the parallel collections used by non-Theravāda schools in India which are preserved in Chinese and partially in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Tibetan, and the various non-Theravāda Vinayas. On this basis, both these sets of texts are generally believed to be the oldest and most authoritative texts on Buddhism by scholars. It is also believed that much of the Pali Canon, which is still used by Theravāda communities, was transmitted to Sri Lanka during the reign of Ashoka. After being orally transmitted (as was the custom in those days for religious texts) for some centuries, were finally committed to writing in the last century BCE, at what the Theravāda usually reckons as the fourth council, in Sri Lanka. Theravāda is one of the first Buddhist schools to commit the whole complete set of its Buddhist canon into writing.[110]

Much of the material in the Canon is not specifically "Theravādan", but is instead the collection of teachings that this school preserved from the early, non-sectarian body of teachings. According to Peter Harvey:

The Theravādans, then, may have added texts to the Canon for some time, but they do not appear to have tampered with what they already had from an earlier period.[111]

The Pali Tipitaka consists of three parts: the Vinaya Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka and Abhidhamma Pitaka. Of these, the Abhidhamma Pitaka is believed to be a later addition to the first two pitakas, which, in the opinion of many scholars, were the only two pitakas at the time of the First Buddhist Council. The Pali Abhidhamma was not recognized outside the Theravāda school.

The Tipitaka is composed of 45 volumes in the Thai edition, 40 in the Burmese and 58 in the Sinhalese, and a full set of the Tipitaka is usually kept in its own (medium-sized) cupboard.

Commentaries

In the 4th or 5th century Buddhaghosa Thera wrote the first Pali commentaries to much of the Tipitaka (which were based on much older manuscripts, mostly in old Sinhalese). After him many other monks wrote various commentaries, which have become part of the Theravāda heritage. These texts do not have the same authority as the Tipitaka does, though Buddhaghosas Visuddhimagga is a cornerstone of the commentarial tradition.

The commentaries, together with the Abhidhamma, define the specific Theravāda heritage. Related versions of the Sutta Pitaka and Vinaya Pitaka were common to all the early Buddhist schools, and therefore do not define only Theravāda, but also the other early Buddhist schools, and perhaps the teaching of Gautama Buddha himself.

Theravāda Buddhists consider much of what is found in the Chinese and Tibetan Mahāyāna scriptural collections to be apocryphal, meaning that they are not authentic words of the Buddha.[112]

Lay and monastic life

Young Burmese monk

Distinction between lay and monastic life

Traditionally, Theravāda Buddhism has observed a distinction between the practices suitable for a lay person and the practices undertaken by ordained monks (in ancient times, there was a separate body of practices for nuns). While the possibility of significant attainment by laymen is not entirely disregarded by the Theravāda, it generally occupies a position of less prominence than in the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, with monastic life being hailed as a superior method of achieving Nirvana.[113] The view that Theravāda, unlike other Buddhist schools, is primarily a monastic tradition has, however, been disputed.

Some Western scholars have erroneously tried to claim that Mahāyāna is primarily a religion for laymen and Theravāda is a primarily monastic religion. Both Mahāyāna and Theravāda have as their foundation strong monastic communities, which are almost identical in their regulations. Schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism without monastic communities of fully ordained monks and nuns are relatively recent and atypical developments, usually based on cultural and historical considerations rather than differences in fundamental doctrine. Both Mahāyāna and Theravāda also provided a clear and important place for lay followers.

— Ron Epstein, "Clearing Up Some Misconceptions about Buddhism"[114]

This distinction between ordained monks and laypeople – as well as the distinction between those practices advocated by the Pali Canon, and the folk religious elements embraced by many monks – have motivated some scholars to consider Theravāda Buddhism to be composed of multiple separate traditions, overlapping though still distinct. Most prominently, the anthropologist Melford Spiro in his work Buddhism and Society separated Burmese Theravāda into three groups: Apotropaic Buddhism (concerned with providing protection from evil spirits), Kammatic Buddhism (concerned with making merit for a future birth), and Nibbanic Buddhism (concerned with attaining the liberation of Nirvana, as described in the Tipitaka). He stresses that all three are firmly rooted in the Pali Canon. These categories are not accepted by all scholars, and are usually considered non-exclusive by those who employ them.[citation needed]

The role of lay people has traditionally been primarily occupied with activities that are commonly termed merit-making (falling under Spiro's category of kammatic Buddhism). Merit-making activities include offering food and other basic necessities to monks, making donations to temples and monasteries, burning incense or lighting candles before images of the Buddha, and chanting protective or merit-making verses from the Pali Canon. Some lay practitioners have always chosen to take a more active role in religious affairs, while still maintaining their lay status. Dedicated lay men and women sometimes act as trustees or custodians for their temples, taking part in the financial planning and management of the temple. Others may volunteer significant time in tending to the mundane needs of local monks (by cooking, cleaning, maintaining temple facilities, etc.). Lay activities have traditionally not extended to study of the Pali scriptures, nor the practice of meditation, though in the 20th century these areas have become more accessible to the lay community, especially in Thailand.

Thai monks on pilgrimage in their orange robes.

A number of senior monastics in the Thai Forest Tradition, including Buddhadasa, Ajahn Maha Bua, Ajahn Plien Panyapatipo, Ajahn Pasanno, and Ajahn Jayasaro, have begun teaching meditation retreats outside of the monastery for lay disciples.

Ajahn Chah, a disciple of Mun Bhuridatta of the Thai Forest Tradition of the Dhammayuttika Nikaya, set up a monastic lineage called Cittaviveka at Chithurst Buddhist Monastery with his disciple Ajahn Sumedho, at Chithurst in West Sussex, England. Ajahn Sumedho later founded the Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in Hertfordshire, which has a retreat center specifically for lay retreats. Sumedho extended this to Harnham in Northumberland as Aruna Ratanagiri under the present guidance of Ajahn Munindo, another disciple of Ajahn Chah.[citation needed]

Monastic vocation

A cave kuti (hut) in the Sri Lankan forest monastery Na Uyana Aranya.

Theravada sources dating back to medieval Sri Lanka (2nd century BCE to 10th century CE) such as the Mahavamsa show that monastic roles in the tradition were often seen as being in a polarity between urban monks (Sinhala: khaamawaasii, Pali: gamavasi) on one end and rural forest monks (Sinhala: aranyawaasii, Pali: araññavasi, nagaravasi, also known as Tapassin) on the other.[115] The ascetic focused monks were known by the names Pamsukulikas (rag robe wearers) and Araññikas (forest dwellers).[116]

The Mahavamsa mentions forest monks associated with the Mahavihara. The Pali Dhammapada Commentary mentions another split based on the "duty of study" and the "duty of contemplation".[117] This second division has traditionally been seen as corresponding with the city - forest split, with the city monks focusing on the vocation of books (ganthadhura) or learning (pariyatti) while the forest monks leaning more towards meditation (vipassanadhura) and practice (patipatti).[118] However this opposition is not consistent, and urban monasteries have often promoted meditation while forest communities have also produced excellent scholars, such as the Island Hermitage of Nyanatiloka.[118]

Scholar monks generally undertake the path of studying and preserving the Pali literature of the Theravāda.[119] Forest monks tend to be the minority among Theravada sanghas and also tend to focus on asceticism (dhutanga) and meditative praxis.[120] They view themselves as living closer to the ideal set forth by the Buddha, and are often perceived as such by lay folk, while at the same time often being on the margins of the Buddhist establishment and on the periphery of the social order.[121]

While this divide seems to have been in existence for some time in the Theravada school, only in the 10th century is a specifically forest monk monastery, mentioned as existing near Anuradhapura, called "Tapavana".[122] This division was then carried over into the rest of Southeast Asia as Theravada spread.

Today there are forest based traditions in most Theravada countries, including the Sri Lankan Forest Tradition, the Thai Forest Tradition as well as lesser known forest based traditions in Burma and Laos, such as the Burmese forest based monasteries (taw"yar) of Pa Auk Sayadaw.[123] In Thailand, forest monks are known as phra thudong (ascetic wandering monks) or phra thudong kammathan (wandering ascetic meditator).[124]

Ordination

Candidates for the Buddhist monkhood being ordained as monks in Thailand

The minimum age for ordaining as a Buddhist monk is 20 years, reckoned from conception. However, boys under that age are allowed to ordain as novices (sāmaṇera), performing a ceremony such as shinbyu in Myanmar. Novices shave their heads, wear the yellow robes, and observe the Ten Precepts. Although no specific minimum age for novices is mentioned in the scriptures, traditionally boys as young as seven are accepted. This tradition follows the story of the Buddha's son, Rahula, who was allowed to become a novice at the age of seven. Monks follow 227 rules of discipline, while nuns follow 311 rules.

In most Theravāda countries, it is a common practice for young men to ordain as monks for a fixed period of time. In Thailand and Myanmar, young men typically ordain for the retreat during Vassa, the three-month monsoon season, though shorter or longer periods of ordination are not rare. Traditionally, temporary ordination was even more flexible among Laotians. Once they had undergone their initial ordination as young men, Laotian men were permitted to temporarily ordain again at any time, though married men were expected to seek their wife's permission. Throughout Southeast Asia, there is little stigma attached to leaving the monastic life. Monks regularly leave the robes after acquiring an education, or when compelled by family obligations or ill health.

Ordaining as a monk, even for a short period, is seen as having many virtues. In many Southeast Asian cultures, it is seen as a means for a young man to "repay" his parents for their work and effort in raising him, because the merit from his ordination accrues to them as well. Thai men who have ordained as a monk may be seen as more fit husbands by Thai women, who refer to men who have served as monks with a colloquial term meaning "ripe" to indicate that they are more mature and ready for marriage. Particularly in rural areas, temporary ordination of boys and young men traditionally gave peasant boys an opportunity to gain an education in temple schools without committing to a permanent monastic life.

In Sri Lanka, temporary ordination is not practised, and a monk leaving the order is frowned upon. The continuing influence of the caste system in Sri Lanka plays a role in the taboo against temporary or permanent ordination as a bhikkhu in some orders. Though Sri Lankan orders are often organized along caste lines, men who ordain as monks temporarily pass outside of the conventional caste system, and as such during their time as monks may act (or be treated) in a way that would not be in line with the expected duties and privileges of their caste.[citation needed]

Men and women born in Western countries, who become Buddhists as adults, wish to become monks or nuns. It is possible, and one can live as a monk or nun in the country they were born in, seek monks or nuns which has gathered in a different Western country or move to a monastery in countries like Sri Lanka or Thailand. It is seen as being easier to live a life as a monk or nun in countries where people generally live by the culture of Buddhism, since it is difficult to live by the rules of a monk or a nun in a Western country. For instance, a Theravāda monk or nun is not allowed to work, handle money, listen to music, cook and so on, which are extremely difficult rules to live by in cultures which do not embrace Buddhism.[citation needed]

Some of the more well-known Theravādan monks are Mun Bhuridatta, Ajahn Chah, Ledi Sayadaw, Ajahn Plien Panyapatipo, Ajahn Sumedho, Ajahn Khemadhammo, Ajahn Brahm, Bhikkhu Bodhi, Buddhadasa, Mahasi Sayadaw, Nyanaponika Thera, Preah Maha Ghosananda, U Pandita, Ajahn Amaro, Ajahn Sucitto, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Walpola Rahula, Henepola Gunaratana, Bhante Yogavacara Rahula and Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro.

Monastic practices

A Buddhist Monk chants evening prayers inside a monastery located near the town of Kantharalak, Thailand.

The practices usually vary in different sub-schools and monasteries within Theravāda. But in the most orthodox forest monastery, the monk usually models his practice and lifestyle on that of the Buddha and his first generation of disciples by living close to nature in forest, mountains and caves. Forest monasteries still keep alive the ancient traditions through following the Buddhist monastic code of discipline in all its detail and developing meditation in secluded forests.