The Dunwich Horror

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| "The Dunwich Horror" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | H. P. Lovecraft |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror |

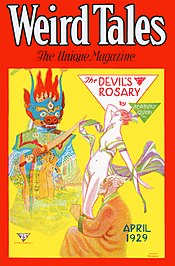

| Published in | Weird Tales |

| Publication type | Periodical |

| Media type | Print (Magazine) |

| Publication date | April, 1929 |

"The Dunwich Horror" is a horror short story by American writer H. P. Lovecraft. Written in 1928, it was first published in the April 1929 issue of Weird Tales (pp. 481–508). It takes place in Dunwich, a fictional town in Massachusetts. It is considered one of the core stories of the Cthulhu Mythos.

Contents

1 Plot

2 Characters

3 Inspiration

3.1 Geographical

3.2 Literary

4 Reception

5 Cthulhu Mythos

6 Adaptations

7 Short story collection

8 Influence

9 References

10 Sources

11 External links

Plot

In the isolated, desolate, decrepit village of Dunwich, Massachusetts, Wilbur Whateley is the hideous son of Lavinia Whateley, a deformed and unstable albino mother, and an unknown father (alluded to in passing by mad Old Whateley, as "Yog-Sothoth"). Strange events surround his birth and precocious development. Wilbur matures at an abnormal rate, reaching manhood within a decade. Locals shun him and his family, and animals fear and despise him due to his odor. All the while, his sorcerer grandfather indoctrinates him into certain dark rituals and the study of witchcraft. Various locals grow suspicious after Old Whateley buys more and more cattle, yet the number of his herd never increases, and the cattle in his field become mysteriously afflicted with severe open wounds.

Wilbur and his grandfather have sequestered an unseen presence at their farmhouse; this being is connected somehow to Yog-Sothoth. Year by year, this unseen entity grows to monstrous proportions, requiring the two men to make frequent modifications to their residence. People begin to notice a trend of cattle mysteriously disappearing. Wilbur's grandfather dies, and his mother disappears soon afterwards. The colossal entity eventually occupies the whole interior of the farmhouse.

Wilbur ventures to Miskatonic University in Arkham to procure their copy of the Necronomicon – Miskatonic's library is one of only a handful in the world to stock an original. The Necronomicon has spells that Wilbur can use to summon the Old Ones, but his family's copy is damaged and lacks the page he needs to open the "door." When the librarian, Dr. Henry Armitage, refuses to release the university's copy to him (and, by sending warnings to other libraries, thwarts Wilbur's efforts to consult their copies), Wilbur breaks into the library at night to steal it. A guard dog, maddened by Wilbur's alien body odor, attacks and kills him with unusual ferocity. When Dr. Armitage and two other professors, Warren Rice and Francis Morgan, arrive on the scene, they see Wilbur's semi-human corpse before it melts completely, leaving no evidence.

With Wilbur dead, no one attends to the mysterious presence growing in the Whateley farmhouse. Early one morning, the farmhouse explodes and the thing, an invisible monster, rampages across Dunwich, cutting a path through fields, trees, and ravines, and leaving huge "prints" the size of tree trunks. The monster eventually makes forays into inhabited areas. The invisible creature terrorizes Dunwich for several days, killing two families and several policemen, until Armitage, Rice, and Morgan arrive with the knowledge and weapons needed to kill it. The use of a magic powder renders it visible just long enough to send one of the crew into shock. The barn-sized monster screams for help – in English – just before the spell destroys it, leaving a huge burned area. In the end, its nature is revealed: it is Wilbur's twin brother, though it "looked more like the father than Wilbur did."

Characters

- Old Whateley

- Lavinia Whateley's "aged and half-insane father, about whom the most frightful tales of magic had been whispered in his youth".[1] He has a large collection of "rotting ancient books and parts of books" which he uses to "instructs and catechise" his grandson Wilbur.[2] He dies of natural causes on August 2, 1924.[3] Whateley was given no certain first name by Lovecraft, although Fungi from Yuggoth mentions a John Whateley; he is referred to as "Noah Whateley" in the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game. According to S. T. Joshi, "It is not certain where Lovecraft got the name Whateley," though there is a small town called Whately in northwestern Massachusetts near the Mohawk Trail, which Lovecraft hiked several times, including in the summer of 1928.[4] Robert M. Price's short story "Wilbur Whateley Waiting" emphasizes the obvious pun in the name.[5]

- Lavinia Whateley

- One of Lovecraft's very few female characters. Born circa 1878, Lavinia Whateley is the spinster daughter of Old Whateley whose mother met an "unexplained death by violence" when Lavinia was 12. She is described as a somewhat deformed, unattractive albino woman...a lone creature given to wandering amidst thunderstorms in the hills and trying to read the great odorous books which her father had inherited through two centuries of Whateleys.... She had never been to school, but was filled with disjointed scraps of ancient lore that Old Whateley had taught her.... Isolated among strange influences, Lavinia was fond of wild and grandiose day-dreams and singular occupations. Elsewhere, she is called "slatternly [and] crinkly-haired". In 1913, she gave birth to Wilbur Whately by an unknown father, later revealed to be Yog-Sothoth. On Halloween night in 1926, she disappeared under mysterious circumstances, presumably killed or sacrificed by her son.

- Wilbur Whateley

- Born February 2, 1913 at 5 a.m. to Lavinia Whateley and Yog-Sothoth. Described as a "dark, goatish-looking infant"[6]—neighbors refer to him as "Lavinny's black brat"[7]—he shows extreme precocity: "Within three months of his birth, he had attained a size and muscular power not usually found in infants under a full year of age.... At seven months, he began to walk unassisted,"[8] and he "commenced to talk...at the age of only eleven months."[7] At three years of age, "he looked like a boy of ten,"[9] while at four and a half, he "looked like a lad of fifteen. His lips and cheeks were fuzzy with a coarse dark down, and his voice had begun to break."[10] "Though he shared his mother's and grandfather's chinlessness, his firm and precociously shaped nose united with the expression of his large, dark, almost Latin eyes to give him an air of..well-nigh preternatural intelligence," Lovecraft writes, though at the same time he is "exceedingly ugly...there being something almost goatish or animalistic about his thick lips, large-pored, yellowish skin, coarse crinkly hair, and oddly elongated ears."[7] He dies at the age of fifteen after being mauled by a guard dog while breaking into the Miskatonic library on August 3, 1928. His death scene allows Lovecraft to provide a detailed description of Wilbur's partly nonhuman anatomy: "The thing that lay half-bent on its side in a foetid pool of greenish-yellow ichor and tarry stickiness was almost nine feet tall, and the dog had torn off all the clothing and some of the skin.... It was partly human, beyond a doubt, with very manlike hands and head, and the goatish, chinless face had the stamp of the Whateleys upon it. But the torso and lower parts of the body were teratologically fabulous, so that only generous clothing could ever have enabled it to walk on earth unchallenged or uneradicated. Above the waist it was semi-anthropomorphic; though its chest...had the leathery, reticulated hide of a crocodile or alligator. The back was piebald with yellow and black, and dimly suggested the squamous covering of certain snakes. Below the waist, though, it was the worst; for here all human resemblance left off and sheer phantasy began. The skin was thickly covered with coarse black fur, and from the abdomen a score of long greenish-grey tentacles with red sucking mouths protruded limply. Their arrangement was odd, and seemed to follow the symmetries of some cosmic geometry unknown to earth or the solar system. On each of the hips, deep set in a kind of pinkish, ciliated orbit, was what seemed to be a rudimentary eye; whilst in lieu of a tail there depended a kind of trunk or feeler with purple annular markings, and with many evidences of being an undeveloped mouth or throat. The limbs, save for their black fur, roughly resembled the hind legs of prehistoric earth's giant saurians, and terminated in ridgy-veined pads that were neither hooves nor claws."[11] This death scene bears a marked resemblance to that of Jervase Cradock, a similarly half-human character in Arthur Machen's "The Novel of the Black Seal": "Something pushed out from the body there on the floor, and stretched forth, a slimy, wavering tentacle," Machen writes.[12] Will Murray notes that the goatish, partly reptilian Wilbur Whateley resembles a chimera, a mythological creature referred to in Charles Lamb's epigraph to "The Dunwich Horror".[13] Robert M. Price points out that Wilbur Whateley is in some respects an autobiographical figure for Lovecraft: "Wilbur's being raised by a grandfather instead of a father, his home education from his grandfather's library, his insane mother, his stigma of ugliness (in Lovecraft's case untrue, but a self-image imposed on him by his mother), and his sense of being an outsider all echo Lovecraft himself."[14]

- Henry Armitage

- The head librarian at Miskatonic University. As a young man, he graduated from Miskatonic in 1881 and went on to obtain his doctorate from Princeton University and his Doctor of Letters degree at Johns Hopkins University. Lovecraft noted that while writing "The Dunwich Horror", "[I] found myself identifying with one of the characters (an aged scholar who finally combats the menace) toward the end".[15]

- Francis Morgan

- Professor of Medicine and Comparative Anatomy (or Archaeology) at Miskatonic University. The story refers to him as "lean" and "youngish". In Fritz Leiber's "To Arkham and the Stars"—written in 1966 and apparently set at about that time—Morgan is described as "the sole living survivor of the brave trio who had slain the Dunwich Horror". According to Leiber, Morgan's "research in mescaline and LSD" produced "clever anti-hallucinogens" that were instrumental in curing Danforth's mental illness.[16]

- Warren Rice

- Professor of Classical Languages at Miskatonic University. He is called "stocky" and "iron-grey".

Inspiration

Geographical

In a letter to August Derleth, Lovecraft wrote that "The Dunwich Horror" "takes place amongst the wild domed hills of the upper Miskatonic Valley, far northwest of Arkham, and is based on several old New England legends — one of which I heard only last month during my sojourn in Wilbraham," a town east of Springfield.[17] (One such legend is the notion that whippoorwills can capture the departing soul.)[18]

In another letter, Lovecraft wrote that Dunwich is "a vague echo of the decadent Massachusetts countryside around Springfield — say Wilbraham, Monson and Hampden."[19] Robert M. Price notes that "much of the physical description of the Dunwich countryside is a faithful sketch of Wilbraham," citing a passage from a letter from Lovecraft to Zealia Bishop that "sounds like a passage from 'The Dunwich Horror' itself":

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

When the road dips again there are stretches of marshland that one instinctively dislikes, and indeed almost fears at evening when unseen whippoorwills chatter and the fireflies come out in abnormal profusion to dance to the raucous, creepily insistent rhythms of stridently piping bullfrogs.[20]

The physical model for Dunwich's Sentinel Hill is thought to be Wilbraham Mountain near Wilbraham.[21]

Some researchers have pointed out the story's apparent connections to another Massachusetts region: the area around Athol and points south, in the north-central part of the state (which is where Lovecraft indicates that Dunwich is located). It has been suggested that the name "Dunwich" was inspired by the town of Greenwich, which was deliberately flooded to create the Quabbin Reservoir,[22] although Greenwich and the nearby towns of Dana, Enfield and Prescott actually were not submerged until 1938. Donald R. Burleson points out that several names included in the story—including Bishop, Frye, Sawyer, Rice and Morgan—are either prominent Athol names or have a connection to the town's history.[23]

Athol's Sentinel Elm Farm seems to be the source for the name Sentinel Hill.[21] The Bear's Den mentioned in the story resembles an actual cave of the same name visited by Lovecraft in North New Salem, southwest of Athol.[24] (New Salem, like Dunwich, was founded by settlers from Salem—though in 1737, not 1692.[25])

The book Myths and Legends of Our Own Land,[26] by Charles M. Skinner, mentions a "Devil's Hop Yard" near Haddam, Connecticut as a gathering place for witches. The book, which Lovecraft seems to have read, also describes noises emanating from the earth near Moodus, Connecticut, which are similar to the Dunwich sounds decried by Rev. Abijah Hoadley.[27]

Literary

Lovecraft's main literary sources for "The Dunwich Horror" are the stories of Welsh horror writer Arthur Machen, particularly "The Great God Pan" (which is mentioned in the text of "The Dunwich Horror") and "The Novel of the Black Seal". Both Machen stories concern individuals whose death throes reveal them to be only half-human in their parentage. According to Robert M. Price, "'The Dunwich Horror' is in every sense an homage to Machen and even a pastiche. There is little in Lovecraft's story that does not come directly out of Machen's fiction."[28]

Another source that has been suggested[citation needed] is "The Thing in the Woods", by Margery Williams, which is also about two brothers living in the woods, neither of them quite human and one of them less human than the other.

The name Dunwich itself may come from Machen's The Terror, where the name refers to an English town where the titular entity is seen hovering as "a black cloud with sparks of fire in it".[29] Lovecraft also takes Wilbur Whateley's occult terms "Aklo" and "Voorish" from Machen's "The White People".[30]

Lovecraft also seems to have found inspiration in Anthony M. Rud's story "Ooze" (published in Weird Tales, March 1923), which also involved a monster being secretly kept and fed in a house that it subsequently bursts out of and destroys.[31]

The tracks of Wilbur's brother recall those seen in Algernon Blackwood's "The Wendigo", one of Lovecraft's favorite horror stories.[32]Ambrose Bierce's story "The Damned Thing" also involves a monster invisible to human eyes.

Reception

Lovecraft took pride in "The Dunwich Horror", calling it "so fiendish that [Weird Tales editor] Farnsworth Wright may not dare to print it." Wright, however, snapped it up, sending Lovecraft a check for $240, equal to $2800 in modern dollars, the largest single payment for his fiction he had received up to that point.[33]

Kingsley Amis praised "The Dunwich Horror" in New Maps of Hell, listing it as one of Lovecraft's tales that "achieve a memorable nastiness".[34] Lovecraft biographer Lin Carter calls the story "an excellent tale... A mood of tension and gathering horror permeates the story, which culminates in a shattering climax".[35] In his list of "The 13 Most Terrifying Horror Stories", T. E. D. Klein placed "The Dunwich Horror" at number four. [36]Robert M. Price declares that "among the tales of H. P. Lovecraft, 'The Dunwich Horror' remains my favorite."[37]S.T. Joshi, on the other hand, regarded "Dunwich" as "simply an aesthetic mistake on Lovecraft's part", citing its "stock good-versus-evil scenario". However, he has also noted that it is "richly atmospheric."[38]

Cthulhu Mythos

Although Lovecraft first mentioned "Yog-Sothoth" in the novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, it was in "The Dunwich Horror" that he introduced the entity as one of his extra-dimensional Outer Gods. It is also the tale in which the Necronomicon makes the most significant appearance, and the longest direct quote from it appears in the text. Many of the other standards of the Cthulhu Mythos, such as Miskatonic University, Arkham and Dunwich also form integral parts of the tale.

A librarian named Armitage appears in Don Webb's short story "To Mars and Providence", an alternate history where a juvenile Lovecraft is influenced by the events of H.G. Wells's The War of the Worlds.

The biannual NecronomiCon Providence has a "Dr. Henry Armitage Memorial Scholarship Symposium", whose papers are printed by Hippocampus Press.

Adaptations

- The radio drama Suspense adapted "The Dunwich Horror". It stars Academy Award winner Ronald Colman as Henry Armitage, and aired originally on November 1, 1945.[citation needed]

- A film version, The Dunwich Horror, was released in 1970. It starred Dean Stockwell as Wilbur Whateley, Ed Begley as Henry Armitage and Sandra Dee. Les Baxter composed the soundtrack. It was the final film for Begley, who died in April of that year.

- Another film version of the tale starring Jeffrey Combs as Wilbur Whately and directed by Leigh Scott[39] was first broadcast in October 2009 on SyFy. Dean Stockwell also stars in this version, this time as Dr. Henry Armitage. The working title was The Darkest Evil.

- Comics artist Alberto Breccia adapted the story in 1974. It was published in Heavy Metal October 1979 issue.[citation needed]

- Comics artist John Coulthart started to adapt the story in 1989. The unfinished story was published in 1999.[citation needed]

- "The Dunwich Horror", along with "The Picture in the House" and "The Festival", were adapted into short claymation films, and released by Toei Animation as a DVD compilation called H. P. Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror and Other Stories (H・P・ラヴクラフトのダニッチ・ホラー その他の物語, Ecchi Pī Ravukurafuto no Danicchi Horā Sonota no Monogatari) in 2007.[40][41]

- The H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society adapted the story in 2008 as an audio drama titled Dark Adventure Radio Theatre: The Dunwich Horror, similar to their earlier adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness.

- Director Richard Griffin made a modern update of "The Dunwich Horror" called Beyond the Dunwich Horror.[42]

- The story was adapted into an "audio horror movie" in 2010 by Colin Edwards and the sound company Savalas. The recording is essentially an audio drama recorded in 5.1 Surround Sound to create a movie without pictures. It premiered at the Filmhouse cinema in Edinburgh on 23 June, 2010 as part of the 64th Edinburgh International Film Festival. Director/writer Colin Edwards was in attendance along with cast members Greg Hemphill, Innes Smith and Vivien Taylor and sound designer Kahl Henderson.[43]

- In 2011, IDW Publishing began publishing a four-issue limited adaptation of "The Dunwich Horror" by Bram Stoker Award-winning author Joe R. Lansdale and artist Peter Bergting.[44]

- In 2011, Julie Hoverson, through her audio production company 19 Nocturne Boulevard, released an adaptation of "The Dunwich Horror" in a four-part miniseries.[45]

- In 2013, The Company (a Yorkshire amateur dramatics society) produced a stage play adaptation of "The Dunwich Horror" at the Drama Studio at the University of Sheffield.[46]

- In 2016, cartoonist and illustrator Ben Granoff published a graphic novel adaptation.[47][48]

Short story collection

The Dunwich Horror and Others is the title of a collection of H. P. Lovecraft short stories published by Arkham House, containing what August Derleth considered to be the best of Lovecraft's shorter fiction. Originally published in 1963, the 6th printing in 1985 included extensive corrections by S. T. Joshi in order to produce the definitive edition of Lovecraft's works. The collection has an introduction by Robert Bloch, titled "Heritage of Horror", reprinted from the 1982 Ballantine collection, Blood Curdling Tales of Supernatural Horror: The Best of H.P. Lovecraft.

The stories included in The Dunwich Horror and Others are: "In the Vault", "Pickman's Model", "The Rats in the Walls", "The Outsider", "The Colour Out of Space", "The Music of Erich Zann", "The Haunter of the Dark", "The Picture in the House", "The Call of Cthulhu", "The Dunwich Horror", "Cool Air", "The Whisperer in Darkness", "The Terrible Old Man", "The Thing on the Doorstep", "The Shadow Over Innsmouth", and "The Shadow Out of Time".

Influence

- In the episode "The Invisible Monster" from the original 1964/1965 season of the Hanna-Barbera cartoon "Johnny Quest", there is an invisible energy monster that grows larger as it feeds and cuts a swath of destruction through a tropical forest, leaving a trail of large "footprints" behind it – until it is eventually made visible by paint bombs.

- The Leviathan arc of the Gothic soap opera Dark Shadows was heavily influenced by "The Dunwich Horror", as well as other Lovecraft works. The character of Jebez "Jeb" Hawkes is the essence of the Leviathan leader who matures at a rapid rate and transforms into an invisible murderous creature.

John Carpenter's 1994 film In the Mouth of Madness features many allusions to Lovecraft, including a book titled "The Hobbes End Horror".

Neil Gaiman's short story "I, Cthulhu" features a human slave/biographer referred to only as Whateley.- Stoner/doom metal band Electric Wizard released a song on their 2007 album, Witchcult Today, entitled "Dunwich", based around the short story. "We Hate You", from their 2000 album, Dopethrone, contains sound clips from the film.

Lucio Fulci's 1980 movie City of the Living Dead is set in a town named Dunwich.- Joseph Bruchac's children's horror novel, Whisper in the Dark has an albino homicidal serial killer named Wilbur Whatley that decapitated his own parents and was afraid of dogs.

- On his third album, Medallion Animal Carpet, Bob Drake and a collaborator retell the story of "The Dunwich Horror" under the title "Dunwich Confidential".

- The 2008 video game Fallout 3 features a location called "The Dunwich Building," with a mini-story of a man searching for his father, who is in possession of an "old, bloodstained book made of weird leather". The man is found in front of an obelisk under the building, driven insane and turned into a feral ghoul. A later downloadable add-on, Point Lookout, features a quest involving a book with a similar purpose as the Necronomicon and an equally strange name, the Krivbeknih, which can be destroyed in the basement of the Dunwich Building.

- The 2015 video game Fallout 4, sequel to Fallout 3 and set in Massachusetts, features a location called Dunwich Borers, which had been owned by a company named Dunwich Borers LLC.

- "Boojum", a short story by Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette, features a living, sentient space ship (a Boojum) named "Lavinia Whateley" by her pirate crew.[49]

Chiaki Konaka, scriptwriter of the 1995 cyberpunk series Armitage III, reported being influenced by this story when writing the series. Among other signs of influence are the character named Armitage, another character named Lavinia Whateley, and a location variously spelled as Dunwich or "Danich" Hill. However, the actual stories have little in common.- Symphonic deathcore act Lorelei have a song named "The Dunwich Horror".[50]

- The final book in Edward M. Erdelac's Merkabah Rider series, Once Upon A Time In The Weird West, features the elder Whateley.

- Doom metal band Iron Man's 2013 album South of the Earth contains the song "Half Face/Thy Brother's Keeper (Dunwich Pt. 2"), which is based on the story.

- Japanese progressive metal band Ningen Isu recorded a song "Dunwich no Kai" (The Dunwich Horror) in their 1998 album Taihai Geijutsu-ten.[51]

Harry Turtledove's book Nine Drowned Churches is set in Dunwich, England, which is eerily similar to the town in "The Dunwich Horror", right down to the family names, and the protagonist is aware of the events of this story.[52]- The board game Arkham Horror has an expansion simply known as "The Dunwich Horror", in which both the grandfather called "Wizard Whately" and the Dunwich Horror itself appears.[53][54]

References

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 159.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 163.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 166.

^ Joshi, p. 115.

^ Robert M. Price, “Wilbur Whateley Waiting”, The Dunwich Cycle, Robert M. Price, ed., pp. 236–252.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 159.

^ abc Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 162.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 161.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 164.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", p. 165.

^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", pp. 174–175.

^ Cited in Joshi, p. 140.

^ Will Murray, "The Dunwich Chimera and Others: Correlating the Cthulhu Mythos", Lovecraft Studies No. 8 (Spring 1984), pp. 10–24; cited in Joshi, pp. 104, 140.

^ Price, The Dunwich Cycle, p. 236.

^ H. P. Lovecraft, letter to August Derleth, September 1928; cited in Joshi and Schultz, p. 81.

^ Fritz Leiber, "To Arkham and the Stars", Tales of the Lovecraft Mythos, pp. 320–321.

^ Lovecraft, letter to August Derleth, August 4, 1928, cited in Joshi, p. 101.

^ Joshi, p. 113.

^ Lovecraft, Selected Letters Vol. III, pp. 432–433; cited in Joshi, p. 108.

^ Cited in Robert M. Price, The Dunwich Cycle, p. 82.

^ ab Joshi, p. 114.

^ Charles P. Mitchell, The Complete H.P.Lovecraft Filmography p.9 (2001)

^ Donald R. Burleson, "Humour Beneath Horror: Some Sources for 'The Dunwich Horror' and 'The Whisperer in Darkness'", Lovecraft Studies, No. 2 (Spring 1980), pp. 5–15, cited in Joshi, pp. 105, 111, 138; Price, p. 82.

^ Joshi, p. 147.

^ Will Murray, "In Search of Arkham Country Revisited", Lovecraft Studies, Nos. 19/20 (Fall 1989), ppp. 65–69; cited in Joshi, p. 110.

^ Myths and Legends of Our Own Land, Charles M. Skinner, 1896; online version available from Project Gutenberg

^ Joshi, p. 112.

^ Price, pp. ix–x.

^ Price, p. 1.

^ Price, p. 48.

^ Joshi, pp. 118, 152.

^ Joshi, pp. 144–145.

^ Lovecraft, Selected Letters Vol. II, p. 240; cited in Joshi, p. 101.

^ Kingsley Amis, New Maps of Hell:A Survey of Science Fiction. Victor Gollancz, 1961, p.25.

^ Lin Carter, Lovecraft: A Look Behind the Cthulhu Mythos, pp. 71–72.

^ T. E. D. Klein, "The 13 Most Terrifying Horror Stories" in Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine, July–August 1983, (p. 63).

^ Robert M. Price, "What Roodmas Horror", The Dunwich Cycle, p. ix.

^ Joshi, pp. 16–17.

^ The Dunwich Horror on IMDb

^ "H・P・ラヴクラフトのダニッチ・ホラー その他の物語" [H. P. Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror and Other Stories] (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-12..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "H.P.Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror and Other Stories is released on August 28, 2007 under the Ganime DVD label" (Press release). Toei Animation. 5 June 2007. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

^ Fife, Tim (15 May 2008). "Beyond Providence, Beyond Death; an Interview with Beyond the Dunwich Horror director Richard Griffin". CinemaSuicide.com. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

^ "H.P. Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror". Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

^ "IDW Announces H.P. Lovecraft Adaptation Comic Series" (Press release). IDW Publishing. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

^ "19 Nocturne presents The Dunwich Horror – part 1 of 4". 19 Nocturne Boulevard. 8 October 2011. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

^ "Dunwich Horror 2013 stage play review".

^

@MidtownComics (11 Aug 2016). "Midtown's Benjamin Granoff adapted H.P. Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror from Bag & Board Studios" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

^ Granoff, Benjamin (2016). H.P. Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror. Bag & Board Studios. ISBN 978-1-68419-956-3.

^ "Boojum by Elizabeth Bear & Sarah Monette". Lightspeed. September 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

^ "The Dunwich Horror|Lorelei". Bandcamp. Archived from the original on 2013-01-09. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

^ "Nigen Isu discography". Archived from the original on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

^ Turtledove, Harry (2015), "Nine Drowned Churches", That Is Not Dead, pp. 213–224

^ "Arkham Horror: Dunwich Horror Expansion". BoardGameGeek. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

^ "The Dunwich Horror (Arkham Horror Expansion)". Fantasy Flight Games. 2006. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

Sources

Lovecraft, Howard P. (1984) [1928]. "The Dunwich Horror". In S. T. Joshi (ed.). The Dunwich Horror and Others (9th corrected printing ed.). Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN 0-87054-037-8.CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link) Definitive version.

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: The Dunwich Horror |

Full-text at The H. P. Lovecraft Archive

The Dunwich Horror on the Internet Archive (episode 154, 1 November 1945, radio drama)

The Dunwich Horror title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database The Dunwich Horror public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Dunwich Horror public domain audiobook at LibriVox