Woman

Multi tool use

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

A woman mechanic

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

Society

|

|

|

|

Popular culture

|

Sports

See also: List of sports |

By country

|

|

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Feminism | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

History

| ||||||||

Variants (general)

| ||||||||

Variants (religious)

| ||||||||

Concepts

| ||||||||

Outlooks

| ||||||||

Theory

| ||||||||

By country

| ||||||||

Lists and categories

| ||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Feminist philosophy |

|---|

|

Major works |

|

Major theorists |

|

Ideas |

|

Journals |

|

Category |

|

A woman is a female human being. The word woman is usually reserved for an adult, with girl being the usual term for a female child or adolescent. The plural women is also sometimes used for female humans, regardless of age, as in phrases such as "women's rights". Women with typical genetic development are usually capable of giving birth from puberty until menopause. There are also trans women (those who have a male sex assignment that does not align with their gender identity),[1] and intersex women (those born with sexual characteristics that do not fit typical notions of male or female).

Contents

1 Etymology

1.1 Biological symbol

2 Terminology

3 History

4 Biology and sex

5 Health

6 Reproductive rights and freedom

7 Culture and gender roles

7.1 Violence against women

8 Clothing, fashion and dress codes

9 Fertility and family life

10 Religion

11 Education

11.1 Literacy

11.2 OECD countries

11.2.1 Education

11.2.2 Jobs

12 Women in politics

13 Science, literature and art

14 See also

15 References

16 Further reading

17 External links

Etymology

The spelling of "woman" in English has progressed over the past millennium from wīfmann[2] to wīmmann to wumman, and finally, the modern spelling woman.[3] In Old English, wīfmann meant "female human", whereas wēr meant "male human". Mann or monn had a gender-neutral meaning of "human", corresponding to Modern English "person" or "someone"; however, subsequent to the Norman Conquest, man began to be used more in reference to "male human", and by the late 13th century had begun to eclipse usage of the older term wēr.[4] The medial labial consonants f and m in wīfmann coalesced into the modern form "woman", while the initial element wīf, which meant "female", underwent semantic narrowing to the sense of a married woman ("wife").

It is a popular misconception[5] that the term "woman" is etymologically connected to "womb". "Womb" is actually from the Old English word wambe meaning "stomach" (modern German retains the colloquial term "Wampe" from Middle High German for "potbelly").[6][7]

Biological symbol

The symbol for the planet and goddess Venus or Aphrodite in Greek is the sign also used in biology for the female sex.[8] It is a stylized representation of the goddess Venus's hand-mirror or an abstract symbol for the goddess: a circle with a small equilateral cross underneath. The Venus symbol also represented femininity, and in ancient alchemy stood for copper. Alchemists constructed the symbol from a circle (representing spirit) above an equilateral cross (representing matter).

Terminology

Womanhood is the period in a human female's life after she has passed through childhood and adolescence, generally around age 18.

The word woman can be used generally, to mean any female human,[citation needed] or specifically, to mean an adult female human as contrasted with girl. The word girl originally meant "young person of either sex" in English;[9] it was only around the beginning of the 16th century that it came to mean specifically a female child.[10] The term girl is sometimes used colloquially to refer to a young or unmarried woman; however, during the early 1970s, feminists challenged such use because the use of the word to refer to a fully grown woman may cause offence. In particular, previously common terms such as office girl are no longer widely used. Conversely, in certain cultures which link family honor with female virginity, the word girl (or its equivalent in other languages) is still used to refer to a never-married woman; in this sense it is used in a fashion roughly analogous to the more-or-less obsolete English maid or maiden.

There are various words used to refer to the quality of being a woman. The term "womanhood" merely means the state of being a woman, having passed the menarche; "femininity" is used to refer to a set of typical female qualities associated with a certain attitude to gender roles; "womanliness" is like "femininity", but is usually associated with a different view of gender roles; "femaleness" is a general term, but is often used as shorthand for "human femaleness";[citation needed] "distaff" is an archaic adjective derived from women's conventional role as a spinner, now used only as a deliberate archaism.

Menarche, the onset of menstruation, occurs on average at age 12–13. Many cultures have rites of passage to symbolize a girl's coming of age, such as confirmation in some branches of Christianity,[11]bat mitzvah in Judaism, or even just the custom of a special celebration for a certain birthday (generally between 12 and 21), like the quinceañera of Latin America.

History

The earliest women whose names are known through archaeology include:

Neithhotep (c. 3200 BCE), the wife of Narmer and the first queen of ancient Egypt.[12][13]

Merneith (c. 3000 BCE), consort and regent of ancient Egypt during the first dynasty. She may have been ruler of Egypt in her own right.[14][15]

Merit-Ptah (c. 2700 BCE), also lived in Egypt and is the earliest known female physician and scientist.[16]

Peseshet (c. 2600 BCE), a physician in Ancient Egypt.[17][18]

Puabi (c. 2600 BCE), or Shubad – queen of Ur whose tomb was discovered with many expensive artifacts. Other known pre-Sargonic queens of Ur (royal wives) include Ashusikildigir, Ninbanda, and Gansamannu.[19]

Kugbau (circa 2,500 BCE), a taverness from Kish chosen by the Nippur priesthood to become hegemonic ruler of Sumer, and in later ages deified as "Kubaba".

Tashlultum (c. 2400 BCE), Akkadian queen, wife of Sargon of Akkad and mother of Enheduanna.[20][21]

Baranamtarra (c. 2384 BCE), prominent and influential queen of Lugalanda of Lagash. Other known pre-Sargonic queens of the first Lagash dynasty include Menbara-abzu, Ashume'eren, Ninkhilisug, Dimtur, and Shagshag, and the names of several princesses are also known.

Enheduanna (c. 2285 BCE),[22][23] the high priestess of the temple of the Moon God in the Sumerian city-state of Ur and possibly the first known poet and first named author of either gender.[24]

Shibtu (c. 1775 BCE), king Zimrilim's consort and queen of the Syrian city-state of Mari. During her husband's absence, she ruled as regent of Mari and enjoyed extensive administrative powers as queen.[25]

Biology and sex

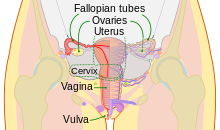

The human female reproductive system

Spectral karyotype of a human female

Photograph of an adult female human, with an adult male for comparison. Note that the body hair of both models is removed.

In terms of biology, the female sex organs are involved in the reproductive system, whereas the secondary sex characteristics are involved in nurturing children[citation needed] or, in some cultures, attracting a mate. The ovaries, in addition to their regulatory function producing hormones, produce female gametes called eggs which, when fertilized by male gametes (sperm), form new genetic individuals. The uterus is an organ with tissue to protect and nurture the developing fetus and muscle to expel it when giving birth. The vagina is used in copulation and birthing, although the term vagina is often colloquially and incorrectly used in the English language for the vulva or external female genitalia, which consists of (in addition to the vagina) the labia, the clitoris, and the female urethra. The breast evolved from the sweat gland to produce milk, a nutritious secretion that is the most distinctive characteristic of mammals, along with live birth. In mature women, the breast is generally more prominent than in most other mammals; this prominence, not necessary for milk production, is probably at least partially the result of sexual selection. (For other ways in which men commonly differ physically from women, see man.)[citation needed]

During early fetal development, embryos of both sexes appear gender-neutral. As in cases without two sexes, such as species that reproduce asexually, the gender-neutral appearance is closer to female than to male. A fetus usually develops into a male if it is exposed to a significant amount of testosterone (typically because the fetus has a Y chromosome from the father). Otherwise, the fetus usually develops into a female, typically when the fetus has an X chromosome from the father, but also when the father contributed neither an X nor Y chromosome. Later at puberty, estrogen feminizes a young woman, giving her adult sexual characteristics.[citation needed]

An imbalance of maternal hormonal levels and some chemicals (or drugs) may alter the secondary sexual characteristics of fetuses. Most women have the karyotype 46,XX, but around one in a thousand will be 47,XXX, and one in 2500 will be 45,X. This contrasts with the typical male karotype of 46,XY; thus, the X and Y chromosomes are known as female and male, respectively. Because humans inherit mitochondrial DNA only from the mother's ovum, genetic studies of the female line tend to focus on mitochondrial DNA.[citation needed]

Whether or not a child is considered female does not always determine whether or not the child later will identify themselves that way (see gender identity). For instance, intersex individuals, who have mixed physical and/or genetic features, may use other criteria in making a clear determination. At birth, babies may be assigned a gender based on their genitalia. In some cases, even if a child had XX chromosomes, if they were born with a penis, they were raised as a male.[26] There are also trans women who were assigned as male at birth, but identify as women;[27] there are varying social, legal, and individual definitions with regard to these issues.[citation needed]

"The Life & Age of Woman – Stages of Woman's Life from the Cradle to the Grave",1849

Although fewer females than males are born (the ratio is around 1:1.05), because of a longer life expectancy there are only 81 men aged 60 or over for every 100 women of the same age. Women typically have a longer life expectancy than men.[28] This is due to a combination of factors: genetics (redundant and varied genes present on sex chromosomes in women); sociology (such as the fact that women are not expected in most modern nations to perform military service); health-impacting choices (such as suicide or the use of cigarettes, and alcohol); the presence of the female hormone estrogen, which has a cardioprotective effect in premenopausal women; and the effect of high levels of androgens in men. Out of the total human population in 2015, there were 101.8 men for every 100 women.[29]

Woman nursing her infant

Girls' bodies undergo gradual changes during puberty, analogous to but distinct from those experienced by boys. Puberty is the process of physical changes by which a child's body matures into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction to enable fertilisation. It is initiated by hormonal signals from the brain to the gonads-either the ovaries or the testes. In response to the signals, the gonads produce hormones that stimulate libido and the growth, function, and transformation of the brain, bones, muscle, blood, skin, hair, breasts, and sexual organs. Physical growth—height and weight—accelerates in the first half of puberty and is completed when the child has developed an adult body. Until the maturation of their reproductive capabilities, the pre-pubertal, physical differences between boys and girls are the genitalia, the penis and the vagina. Puberty is a process that usually takes place between the ages 10–16, but these ages differ from girl to girl. The major landmark of girls' puberty is menarche, the onset of menstruation, which occurs on average between ages 12–13.[30][31][32][33]

Most girls go through menarche and are then able to become pregnant and bear children. This generally requires internal fertilization of her eggs with the sperm of a man through sexual intercourse, though artificial insemination or the surgical implantation of an existing embryo is also possible (see reproductive technology). The study of female reproduction and reproductive organs is called gynaecology.[34]

Health

Pregnant woman

Women's health refers to health issues specific to human female anatomy. There are some diseases that primarily affect women, such as lupus. Also, there are some sex-related illnesses that are found more frequently or exclusively in women, e.g., breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer. Women and men may have different symptoms of an illness and may also respond to medical treatment differently. This area of medical research is studied by gender-based medicine.[35]

The issue of women's health has been taken up by many feminists, especially where reproductive health is concerned. Women's health is positioned within a wider body of knowledge cited by, amongst others, the World Health Organization, which places importance on gender as a social determinant of health.[36]

Maternal mortality or maternal death is defined by WHO as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes."[37] About 99% of maternal deaths occur in developing countries. More than half of them occur in sub-Saharan Africa and almost one third in South Asia. The main causes of maternal mortality are severe bleeding (mostly bleeding after childbirth), infections (usually after childbirth), pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, unsafe abortion, and pregnancy complications from malaria and HIV/AIDS.[38] Most European countries, Australia, as well as Japan and Singapore are very safe in regard to childbirth, while Sub-Saharan countries are the most dangerous.[39]

Reproductive rights and freedom

A poster from a 1921 eugenics conference displays the U.S. states that had implemented sterilization legislation

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics has stated that:[40]

- (...) the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Equal relationships between women and men in matters of sexual relations and reproduction, including full respect for the integrity of the person, require mutual respect, consent and shared responsibility for sexual behavior and its consequences.

Violations of reproductive rights include forced pregnancy, forced sterilization and forced abortion.

Forced sterilization was practiced during the first half of the 20th century by many Western countries. Forced sterilization and forced abortion are reported to be currently practiced in countries such as Uzbekistan and China.[41][42][43][44][45][46]

The lack of adequate laws on sexual violence combined with the lack of access to contraception and/or abortion are a cause of enforced pregnancy (see pregnancy from rape).[citation needed]

Culture and gender roles

A woman weaving. Textile work is traditionally and historically a female occupation in many cultures.

In many prehistoric cultures, women assumed a particular cultural role. In hunter-gatherer societies, women were generally the gatherers of plant foods, small animal foods and fish, while men hunted meat from large animals.[citation needed]

In more recent history, gender roles have changed greatly. Originally, starting at a young age, aspirations occupationally are typically veered towards specific directions according to gender.[47] Traditionally, middle class women were involved in domestic tasks emphasizing child care. For poorer women, especially working class women, although this often remained an ideal,[specify] economic necessity compelled them to seek employment outside the home. Many of the occupations that were available to them were lower in pay than those available to men.[citation needed]

As changes in the labor market for women came about, availability of employment changed from only "dirty", long hour factory jobs to "cleaner", more respectable office jobs where more education was demanded. Women's participation in the U.S. labor force rose from 6% in 1900 to 23% in 1923. These shifts in the labor force led to changes in the attitudes of women at work, allowing for the revolution which resulted in women becoming career and education oriented.[citation needed]

During World War II, some women performed roles which would otherwise have been considered male jobs by the culture of the time

In the 1970s, many female academics, including scientists, avoided having children. However, throughout the 1980s, institutions tried to equalize conditions for men and women in the workplace. Even so, the inequalities at home stumped women's opportunities to succeed as far as men. Professional women are still generally considered responsible for domestic labor and child care. As people would say, they have a "double burden" which does not allow them the time and energy to succeed in their careers. Furthermore, though there has been an increase in the endorsement of egalitarian gender roles in the home by both women and men, a recent research study showed that women focused on issues of morality, fairness, and well-being, while men focused on social conventions.[48] Until the early 20th century, U.S. women's colleges required their women faculty members to remain single, on the grounds that a woman could not carry on two full-time professions at once. According to Schiebinger, "Being a scientist and a wife and a mother is a burden in society that expects women more often than men to put family ahead of career." (p. 93).[49]

Movements advocate equality of opportunity for both sexes and equal rights irrespective of gender. Through a combination of economic changes and the efforts of the feminist movement,[specify] in recent decades women in many societies now have access to careers beyond the traditional homemaker.

Although a greater number of women are seeking higher education, their salaries are often less than those of men. CBS News claimed in 2005 that in the United States women who are ages 30 to 44 and hold a university degree make 62 percent of what similarly qualified men do, a lower rate than in all but three of the 19 countries for which numbers are available. Some Western nations with greater inequity in pay are Germany, New Zealand and Switzerland.[50]

Violence against women

A campaign against female genital mutilation – a road sign near Kapchorwa, Uganda

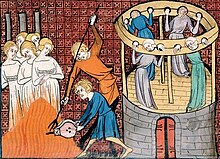

Burning witches, with others held in Stocks

A young ethnic Chinese woman from one of the Imperial Japanese Army's "comfort battalions" is interviewed by an Allied officer.

The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women defines "violence against women" as:[51]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

and identifies three forms of such violence: that which occurs in the family, that which occurs within the general community, and that which is perpetrated or condoned by the State. It also states that "violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women".[52]

Violence against women remains a widespread problem, fueled, especially outside the West, by patriarchal social values, lack of adequate laws, and lack of enforcement of existing laws. Social norms that exist in many parts of the world hinder progress towards protecting women from violence. For example, according to surveys by UNICEF, the percentage of women aged 15–49 who think that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances is as high as 90% in Afghanistan and Jordan, 87% in Mali, 86% in Guinea and Timor-Leste, 81% in Laos, and 80% in the Central African Republic.[53] A 2010 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that stoning as a punishment for adultery was supported by 82% of respondents in Egypt and Pakistan, 70% in Jordan, 56% Nigeria, and 42% in Indonesia.[54]

Specific forms of violence that affect women include female genital mutilation, sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, honor killings, acid throwing, and dowry related violence. Governments can be complicit in violence against women, for instance through practices such as stoning (as punishment for adultery).

There have also been many forms of violence against women which have been prevalent historically, notably the burning of witches, the sacrifice of widows (such as sati) and foot binding. The prosecution of women accused of witchcraft has a long tradition; for example, during the early modern period (between the 15th and 18th centuries), witch trials were common in Europe and in the European colonies in North America. Today, there remain regions of the world (such as parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, rural North India, and Papua New Guinea) where belief in witchcraft is held by many people, and women accused of being witches are subjected to serious violence.[55][56][57] In addition, there are also countries which have criminal legislation against the practice of witchcraft. In Saudi Arabia, witchcraft remains a crime punishable by death, and in 2011 the country beheaded a woman for 'witchcraft and sorcery'.[58][59]

It is also the case that certain forms of violence against women have been recognized as criminal offenses only during recent decades, and are not universally prohibited, in that many countries continue to allow them. This is especially the case with marital rape.[60][61] In the Western World, there has been a trend towards ensuring gender equality within marriage and prosecuting domestic violence, but in many parts of the world women still lose significant legal rights when entering a marriage.[62]

Sexual violence against women greatly increases during times of war and armed conflict, during military occupation, or ethnic conflicts; most often in the form of war rape and sexual slavery. Contemporary examples of sexual violence during war include rape during the Armenian Genocide, rape during the Bangladesh Liberation War, rape in the Bosnian War, rape during the Rwandan genocide, and rape during Second Congo War. In Colombia, the armed conflict has also resulted in increased sexual violence against women.[63] The most recent case was the sexual jihad done by ISIL where 5000–7000 Yazidi and Christian girls and children were sold into sexual slavery during the genocide and rape of Yazidi and Christian women, some of which jumped to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement.[64]

Laws and policies on violence against women vary by jurisdiction. In the European Union, sexual harassment and human trafficking are subject to directives.[65][66]

Clothing, fashion and dress codes

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Women in different parts of the world dress in different ways, with their choices of clothing being influenced by local culture, religious tenets, traditions, social norms, and fashion trends, amongst other factors. Different societies have different ideas about modesty. However, in many jurisdictions, women's choices in regard to dress are not always free, with laws limiting what they may or may not wear. This is especially the case in regard to Islamic dress. While certain jurisdictions legally mandate such clothing (the wearing of the headscarf), other countries forbid or restrict the wearing of certain hijab attire (such as burqa/covering the face) in public places (one such country is France – see French ban on face covering). These laws are highly controversial.[67]

Fertility and family life

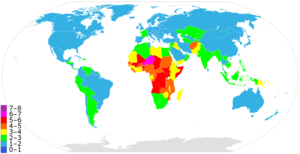

Map of countries by fertility rate (2018), according to the CIA World Factbook

![Percentage of births to unmarried women, selected countries, 1980 and 2007.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/12/Non_marital_by_countries.gif)

Mother and child, in Bhutan

The total fertility rate (TFR) – the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime — differs significantly between different regions of the world. In 2016, the highest estimated TFR was in Niger (6.62 children born per woman) and the lowest in Singapore (0.82 children/woman).[69] While most Sub-Saharan African countries have a high TFR, which creates problems due to lack of resources and contributes to overpopulation, most Western countries currently experience a sub replacement fertility rate which may lead to population ageing and population decline.

In many parts of the world, there has been a change in family structure over the past few decades. For instance, in the West, there has been a trend of moving away from living arrangements that include the extended family to those which only consist of the nuclear family. There has also been a trend to move from marital fertility to non-marital fertility. Children born outside marriage may be born to cohabiting couples or to single women. While births outside marriage are common and fully accepted in some parts of the world, in other places they are highly stigmatized, with unmarried mothers facing ostracism, including violence from family members, and in extreme cases even honor killings.[70][71] In addition, sex outside marriage remains illegal in many countries (such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan,[72] Afghanistan,[73][74] Iran,[74] Kuwait,[75] Maldives,[76] Morocco,[77] Oman,[78] Mauritania,[79] United Arab Emirates,[80][81] Sudan,[82] and Yemen[83]).

The social role of the mother differs between cultures. In many parts of the world, women with dependent children are expected to stay at home and dedicate all their energy to child raising, while in other places mothers most often return to paid work (see working mother and stay-at-home mother).

Religion

Particular religious doctrines have specific stipulations relating to gender roles, social and private interaction between the sexes, appropriate dressing attire for women, and various other issues affecting women and their position in society. In many countries, these religious teachings influence the criminal law, or the family law of those jurisdictions (see Sharia law, for example). The relation between religion, law and gender equality has been discussed by international organizations.[84]

Education

Single-sex education has traditionally been dominant and is still highly relevant. Universal education, meaning state-provided primary and secondary education independent of gender, is not yet a global norm, even if it is assumed in most developed countries. In some Western countries, women have surpassed men at many levels of education. For example, in the United States in 2005/2006, women earned 62% of associate degrees, 58% of bachelor's degrees, 60% of master's degrees, and 50% of doctorates.[2]

Women attending an adult literacy class in the El Alto section of La Paz, Bolivia

A female biologist weighs a desert tortoise before release

Literacy

World literacy is lower for females than for males. The CIA World Factbook presents an estimate from 2010 which shows that 80% of women are literate, compared to 88.6% of men (aged 15 and over). Literacy rates are lowest in South and West Asia, and in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa.[85]

OECD countries

Education

The educational gender gap in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries has been reduced over the last 30 years. Younger women today are far more likely to have completed a tertiary qualification: in 19 of the 30 OECD countries, more than twice as many women aged 25 to 34 have completed tertiary education than have women aged 55 to 64. In 21 of 27 OECD countries with comparable data, the number of women graduating from university-level programmes is equal to or exceeds that of men. 15-year-old girls tend to show much higher expectations for their careers than boys of the same age.[86]

While women account for more than half of university graduates in several OECD countries, they receive only 30% of tertiary degrees granted in science and engineering fields, and women account for only 25% to 35% of researchers in most OECD countries.[87]

There is a common misconception that women have still not advanced in achieving academic degrees. According to Margaret Rossiter, a historian of science, women now earn 54 percent of all bachelor's degrees in the United States. However, although there are more women holding bachelor's degrees than men, as the level of education increases, the more men tend to fit the statistics[clarification needed] instead of women. At the graduate level, women fill 40 percent of the doctorate degrees (31 percent of them being in engineering).[88]

While to this day women are studying at prestigious universities at the same rate as men,[clarification needed] they are not being given the same chance to join faculty. Sociologist Harriet Zuckerman has observed that the more prestigious an institute is, the more difficult and time-consuming it will be for women to obtain a faculty position there. In 1989, Harvard University tenured its first woman in chemistry, Cynthia Friend, and in 1992 its first woman in physics, Melissa Franklin. She also observed that women were more likely to hold their first professional positions as instructors and lecturers while men are more likely to work first in tenure positions. According to Smith and Tang, as of 1989, 65 percent of men and only 40 percent of women held tenured positions and only 29 percent of all scientists and engineers employed as assistant professors in four-year colleges and universities were women.[89]

Jobs

In 1992, women earned 9 percent of the PhDs awarded in engineering, but only one percent of those women became professors.[citation needed] In 1995, 11 percent of professors in science and engineering were women. In relation, only 311 deans of engineering schools were women, which is less than 1 percent of the total. Even in psychology, a degree in which women earn the majority of PhDs, they hold a significant amount of fewer tenured positions, roughly 19 percent in 1994.[90]

Women in politics

A world map showing female governmental participation by country, 2010

Benazir Bhutto was the First Women to head a Democratic government in a Muslim majority country (Pakistan).

Angela Merkel has earned the top spot on the FORBES list of Most Powerful Women In The World for nine of the past 10 years[91]

Women are underrepresented in government in most countries. In October 2013, the global average of women in national assemblies was 22%.[92]Suffrage is the civil right to vote. Women's suffrage in the United States was achieved gradually, first at state and local levels, starting in the late 19th century and early 20th century, and in 1920 women in the US received universal suffrage, with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Some Western countries were slow to allow women to vote; notably Switzerland, where women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971, and in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women were granted the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland;[93][94] and Liechtenstein, in 1984, through a women's suffrage referendum.

Science, literature and art

German composer Clara Schumann in 1878

Women have, throughout history, made contributions to science, literature and art. One area where women have been permitted most access historically was that of obstetrics and gynecology (prior to the 18th century, caring for pregnant women in Europe was undertaken by women; from the mid 18th century onwards, medical monitoring of pregnant women started to require rigorous formal education, to which women did not generally have access, and thus the practice was largely transferred to men).[95][96]

Writing was generally also considered acceptable for upper class women, although achieving success as a female writer in a male dominated world could be very difficult; as a result several women writers adopted a male pen name (e.g. George Sand, George Eliot).[citation needed]

Women have been composers, songwriters, instrumental performers, singers, conductors, music scholars, music educators, music critics/music journalists and other musical professions. There are music movements,[clarification needed] events and genres related to women, women's issues and feminism.[citation needed] In the 2010s, while women comprise a significant proportion of popular music and classical music singers, and a significant proportion of songwriters (many of them being singer-songwriters), there are few women record producers, rock critics and rock instrumentalists. Although there have been a huge number of women composers in classical music, from the Medieval period to the present day, women composers are significantly underrepresented in the commonly performed classical music repertoire, music history textbooks and music encyclopedias; for example, in the Concise Oxford History of Music, Clara Schumann is one of the only female composers who is mentioned.

Women comprise a significant proportion of instrumental soloists in classical music and the percentage of women in orchestras is increasing. A 2015 article on concerto soloists in major Canadian orchestras, however, indicated that 84% of the soloists with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal were men. In 2012, women still made up just 6% of the top-ranked Vienna Philharmonic orchestra. Women are less common as instrumental players in popular music genres such as rock and heavy metal, although there have been a number of notable female instrumentalists and all-female bands. Women are particularly underrepresented in extreme metal genres.[97] Women are also underrepresented in orchestral conducting, music criticism/music journalism, music producing, and sound engineering. While women were discouraged from composing in the 19th century, and there are few women musicologists, women became involved in music education "... to such a degree that women dominated [this field] during the later half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century."[98]

According to Jessica Duchen, a music writer for London's The Independent, women musicians in classical music are "... too often judged for their appearances, rather than their talent" and they face pressure "... to look sexy onstage and in photos."[99] Duchen states that while "[t]here are women musicians who refuse to play on their looks, ... the ones who do tend to be more materially successful."[99]

According to the UK's Radio 3 editor, Edwina Wolstencroft, the classical music industry has long been open to having women in performance or entertainment roles, but women are much less likely to have positions of authority, such as being the leader of an orchestra.[100] In popular music, while there are many women singers recording songs, there are very few women behind the audio console acting as music producers, the individuals who direct and manage the recording process.[101]

See also

- Sex assignment

- Lists of women

Medical:

- Feminine psychology

- Gender differences

Dynamics:

- Femininity

- Feminization (sociology)

- Matriarchy

- Misogyny

- Mitochondrial Eve

- Sexism

- Women as theological figures

- Women in science

Political:

- Gender studies

- Womyn

Exploration:

- List of female explorers and travelers

- Women in space

References

^ Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression in Social Work Practice, edited by Deana F. Morrow and Lori Messinger (2006, .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 0-231-50186-2), p. 8: "Gender identity refers to an individual's personal sense of identity as [man] or [woman], or some combination thereof."

^ "wīfmann": Bosworth & Toller, Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Oxford, 1898–1921) p. 1219. The spelling "wifman" also occurs: C.T. Onions, Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (Oxford, 1966) p. 1011

^ Webster's New World Dictionary, Second College Edition, entry for "woman".

^ man – definition Dictionary.reference.com

^ e.g. The Woman's Bible, By Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Revising Committee, 1898

^ "Germanic etymology : Query result".

^ "dict.cc — wampe — Wörterbuch Englisch-Deutsch".

^ Jose A. Fadul. Encyclopedia of Theory & Practice in Psychotherapy & Counseling p. 337

^ Used in Middle English from c. 1300, meaning 'a child of either sex, a young person'. Its derivation is uncertain, perhaps from an Old English word which has not survived: another theory is that it developed from Old English 'gyrela', meaning 'dress, apparel': or was a diminutive form of a borrowing from another West Germanic Language. (Middle Low German has Gör, Göre, meaning 'girl or small child'.) "girl, n.". OED Online. September 2013. Oxford University Press. 13 September 2013

^ By late 14th century a distinction was arising between female children, often called 'gay girls' – and male, or 'knave girls' -: a1375 William of Palerne (1867) l. 816 ' Whan þe gaye gerles were in-to þe gardin come, Faire floures þei founde.' ('When the gay girls came into the garden, Fair flowers they found.') By the 16th century the unsupported word had begun to mean specifically a female: 1546 J. Heywood Dialogue Prouerbes Eng. Tongue i. x. sig. D, 'The boy thy husbande, and thou the gyrle his wyfe.' The usage meaning 'child of either sex' survived much longer in Irish English. "girl, n.". OED Online. September 2013. Oxford University Press. 13 September 2013

^ "BBC — Religions — Christianity: Confirmation". Retrieved 2017-02-04.

^ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

^ J. Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, 2006, Thames & Hudson.

^ Wilkinson, Toby A.H. (2001). Early dynastic Egypt (1 ed.). Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4.

^ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. p. 140. Thames & Hudson.

ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

^ Merit-Ptah at the University of Alabama.

^ Plinio Prioreschi, A History of Medicine, Horatius Press 1996, p. 334.

^ Lois N. Magner, A History of Medicine, Marcel Dekker 1992, p. 28.

^ Elisabeth Meier Tetlow (2004). Women, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The ancient Near East. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

^ Elisabeth Meier Tetlow (2004). Women, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The ancient Near East. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

^ Michael Roaf (1992). Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East. Stonehenge Press. ISBN 978-0-86706-681-4. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

^ Samuel Kurinsky. "Jewish Women Through The Ages — The Proto-Jewess En Hedu'Anna, Priestess, Poet, Scientist". Hebrew History Federation.

^ Jennifer Bergman (19 July 2001). "Windows to the Universe". www.nestanet.org. National Earth Science Teachers Association.

^ J.M. Adovasio, Olga Soffer, Jake Page (2007). The Invisible Sex: Uncovering the True Roles of Women in Prehistory (1st Smithsonian Books ed.). Smithsonian Books & Collins (Harper Collins Publishers). pp. 278–279. ISBN 978-0-06-117091-1.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Elisabeth Meier Tetlow. Women, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The ancient Near East. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5.

^ Fausto-Sterling, Anne (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. Basic Books. pp. 44–77. ISBN 978-0-465-07714-4. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

^ "Transgender FAQ". GLAAD. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

^ "Why is life expectancy longer for women than it is for men?". Scientific American. 2004-08-30. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

^ "United Nations Statistics Division — Demographic and Social Statistics". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

^ (Tanner, 1990).

^ Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A (April 2003). "Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart". Pediatrics. 111 (4 Pt 1): 844–50. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.844. PMID 12671122.

^ Al-Sahab B, Ardern CI, Hamadeh MJ, Tamim H (2010). "Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth". BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health. 10: 736. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736. PMC 3001737. PMID 21110899.

^ Hamilton-Fairley, Diana. "Obstetrics and Gynaecology" (PDF) (Second ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

^ "gynaecology — definition of gynaecology in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

^ "Advancing the case for gender-based medicine — Horizon 2020 – European Commission". Horizon 2020. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

^ http://www.who.int/social_determinants

^ "WHO | Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births)". Who.int. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "WHO | Maternal mortality". Who.int. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Resolution on Reproductive and Sexual Health | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics". Figo.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Uzbekistan's policy of secretly sterilising women". BBC News. 12 April 2012.

^ "BBC Radio 4 - Crossing Continents, Forced Sterilisation in Uzbekistan". Bbc.co.uk. 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "China 'one-child' policy: Mother of 2 dies after forced sterilization". GlobalPost. 2013-04-09. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Thousands at risk of forced sterilization in China | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "China forced abortion photo sparks outrage". BBC News. 14 June 2012.

^ http://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_HiddenGulag2_Web_5-18.pdf

^ Sharpe, S. (1976). Just like a Girl. London: Penguin.

^ Gere, J., & Helwig, C.C. (2012). Young adults' attitudes and reasoning about gender oles in the family context. "Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36", 301–313. doi: 10.1177/0361684312444272

^ Schiebinger, Londa (1999). Has Feminism Changed Science? : Science and Private Life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 92–103.

^ "U.S. Education Slips In Rankings". CBS News. 13 September 2005.

^ "A/RES/48/104. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women". Un.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ United Nations General Assembly. "A/RES/48/104 – Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women — UN Documents: Gathering a body of global agreements". UN Documents. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Statistics by Area — Attitudes towards wife-beating — Statistical table". Childinfo.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-04. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Muslim Publics Divided on Hamas and Hezbollah | Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project". Pewglobal.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1129&context=djcil#H2N1

^ http://www.mrc.ac.za/crime/witchhunts.pdf

^ "Woman burned alive for 'sorcery' in Papua New Guinea". BBC News. 7 February 2013.

^ "Saudi Arabia: Beheading for 'sorcery' shocking | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Saudi woman beheaded for 'witchcraft and sorcery'". CNN.com. 14 December 2011.

^ In 2006, the UN Secretary-General's In-depth study on all forms of violence against women found that (p. 113): "Marital rape may be prosecuted in at least 104 States. Of these, 32 have made marital rape a specific criminal offence, while the remaining 74 do not exempt marital rape from general rape provisions. Marital rape is not a prosecutable offence in at least 53 States. Four States criminalize marital rape only when the spouses are judicially separated. Four States are considering legislation that would allow marital rape to be prosecuted."[1]

^ In England and Wales, marital rape was made illegal in 1991. The views of Sir Matthew Hale, a 17th-century jurist, published in The History of the Pleas of the Crown (1736), stated that a husband cannot be guilty of the rape of his wife because the wife "hath given up herself in this kind to her husband, which she cannot retract"; in England and Wales this would remain law for more than 250 years, until it was abolished by the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords, in the case of R v R in 1991.

^ For example, in Yemen, marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[2] In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives. The criminal code states at Paragraph 41 that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right; examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom"."Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2012-10-21.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) In the Democratic Republic of Congo the Family Code states that the husband is the head of the household; the wife owes her obedience to her husband; a wife has to live with her husband wherever he chooses to live; and wives must have their husbands' authorization to bring a case in court or to initiate other legal proceedings.[3]

^ "Colombian authorities fail to stop or punish sexual violence against women | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ Ahmed, Havidar (14 August 2014). "The Yezidi Exodus, Girls Raped by ISIS Jump to their Death on Mount Shingal". Rudaw Media Network. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

^ Directive 2002/73/EC — equal treatment of 23 September 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions [4]

^ "Directive 2011/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JH".

^ "Women's right to choose their dress, free of coercion". Amnesty International. 4 March 2011.

^ "Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States". CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. May 13, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency".

^ https://web.archive.org/web/20130501013343/http://www.mrt-rrt.gov.au/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=91cf943a-3fa6-4fce-afec-4ab2c2a356fd

^ "Turkey condemns 'honour killings'". BBC News. 1 March 2004.

^ "Human Rights Voices – Pakistan, August 21, 2008". Eyeontheun.org. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

^ "Home". AIDSPortal. Archived from the original on 2008-10-26.

^ ab "Iran". Travel.state.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01.

^ "United Nations Human Rights Website – Treaty Bodies Database – Document – Summary Record – Kuwait". Unhchr.ch.

^ "Culture of Maldives – history, people, clothing, women, beliefs, food, customs, family, social". Everyculture.com.

^ Fakim, Nora (9 August 2012). "BBC News – Morocco: Should pre-marital sex be legal?". BBC.

^ "Legislation of Interpol member states on sexual offences against children – Oman" (PDF). Interpol. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2007.

^ "2010 Human Rights Report: Mauritania". State.gov. 8 April 2011.

^ Dubai FAQs. "Education in Dubai". Dubaifaqs.com.

^ Judd, Terri (10 July 2008). "Briton faces jail for sex on Dubai beach – Middle East – World". The Independent. London.

^ "Sudan must rewrite rape laws to protect victims". Reuters. 28 June 2007.

^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld | Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa – Yemen". UNHCR.

^ "United Nations News Centre — Harmful practices against women and girls can never be justified by religion – UN expert". Un.org. 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ Education Levels Rising in OECD Countries but Low Attainment Still Hampers Some, [[Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Publication Date: 14 September 2004]. Retrieved December 2006.

^ Women in Scientific Careers: Unleashing the Potential, [[Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,

ISBN 92-64-02537-5, 2006]. Retrieved December 2006.

^ Eisenhart, A. Margaret; Finkel, Elizabeth (2001). Women (Still) Need Not Apply:The Gender and Science Reader. New York: Routledge. pp. 13–23.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Brainard, Susanne G.; Carlin, Linda (2001). A six-year Longitudinal Study of Undergraduate Women in Engineering and Science:The Gender and Science Reader. New York: Routledge. pp. 24–37.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Schiebinger, Londa (1999). Has feminism changed science ?: Meters of Equity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

^ "World's Most Powerful Women". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

^ "Women in Parliaments: World and Regional Averages". Ipu.org. 2011-02-14. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "The Long Way to Women's Right to Vote in Switzerland: a Chronology". History-switzerland.geschichte-schweiz.ch. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ "Experts In Women'S Anti-Discrimination Committee Raise Questions Concerning Reports Of Switzerland On Compliance With Convention". Un.org. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

^ Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 96–98

^ Bynum, W.F., & Porter, Roy, eds. Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine. London and New York: Routledge, 1993: 1051–1052.

^ Julian Schaap and Pauwke Berkers. "Grunting Alone? Online Gender Inequality in Extreme Metal Music" in Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music. Vol. 4, no. 1 (2014) p. 103

^ "Women Composers In American Popular Song". Parlorsongs.com. 1911-03-25. p. 1. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

^ ab "CBC Music". Archived from the original on 2016-03-01.

^ Jessica Duchen. "Why the male domination of classical music might be coming to an end | Music". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

^ Ncube, Rosina (September 2013). "Sounding Off: Why So Few Women In Audio?". Sound on Sound.

Further reading

Chafe, William H., "The American Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic, And Political Roles, 1920–1970", Oxford University Press, 1972.

ISBN 0-19-501785-4

Routledge international encyclopedia of women, 4 vls., ed. by Cheris Kramarae and Dale Spender, Routledge 2000

Women in world history : a biographical encyclopedia, 17 vls., ed. by Anne Commire, Waterford, Conn. [etc.] : Yorkin Publ. [etc.], 1999–2002

Woman In all ages and in all countries in 10 volumes. Illustrated edition deluxe limited to 1,000 numbered copies with an index by Rénald Lévesque

External links

| Look up woman or muliebrity in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Wikisaurus:woman in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Quotations related to Women at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Women at Wikiquote Media related to Women at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Women at Wikimedia Commons- Women's History in America

A History of Women’s Entrance into Medicine in France studies and digitized texts by the BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris) see its digital library Medic@.- Women and Christianity: representations and practices

Opinion of [[Ali Khamenei, leader of Iran, about Women's Issues]