Michael Davitt

Multi tool use

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Michael Davitt | |

|---|---|

Mícheál Mac Dáibhéid | |

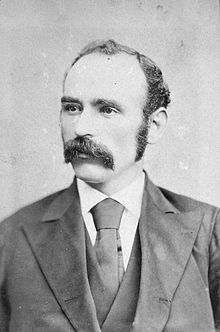

Michael Davitt c. 1878 | |

| Member of Parliament for North-East Cork | |

In office Feb. 1893 – 9 May 1893 | |

| Preceded by | William O'Brien |

| Succeeded by | William Abraham |

| Member of Parliament for Kerry East | |

In office 1895 – 26 October 1899 | |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah Daniel Sheehan |

| Succeeded by | James Boothby Burke Roche |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1846-03-25)25 March 1846 Straide, County Mayo, Ireland |

| Died | 30 May 1906(1906-05-30) (aged 60) Elphis Hospital, Dublin |

| Cause of death | Septicemia |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Political party | Irish Parliamentary Party Irish National Federation |

| Occupation | writer, lecturer, and journalist |

| Known for | Irish Land League activism |

Michael Davitt (Irish: Mícheál Mac Dáibhéid; 25 March 1846 – 30 May 1906) was an Irish republican and agrarian campaigner who founded the Irish National Land League. He was also a labour leader, Home Rule politician and Member of Parliament (MP). He campaigned for Home Rule and was a close ally of Charles Stuart Parnell, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, until the party split over Parnell's divorce and Davitt joined the anti-Parnellite Irish National Federation.

Contents

1 Early years

2 Fenians

3 The Land War

4 Travels and marriage

5 Labour Federation and death

6 Achievements

6.1 Scotland

6.2 Wales

7 Reception

7.1 Memorials

7.2 Popular culture

8 See also

9 Notes

10 Works

11 Further reading

11.1 Primary sources

12 External links

12.1 Institutions

Early years

Lazybeds for potato cultivation, County Mayo

Michael Davitt was born in Straide, County Mayo, Ireland, at the height of the Great Famine, the third of five children born to Martin and Catherine Davitt. They were of poor farming origin, but Davitt's father had a good education and could speak English and Irish. Irish was the household language, and Davitt used it much later in life on a shory visit to Australia.[1]

In 1850, when Michael was four-and-a-half years old, his family was evicted from their home in Straide due to arrears in rent. They entered a local workhouse, but when Catherine discovered that male children over three years of age had to be separated from their mothers, she promptly decided her family should travel to England to find a better life, like many Irish people at this time. They travelled to Dublin with another local family and in November reached Liverpool, walking the 77 kilometres ( 48 miles) to Haslingden, in East Lancashire. There they settled. Davitt was brought up in the closed world of a poor Irish immigrant community with strong nationalist feelings and a deep hatred of landlordism.

After attending infant school Davitt began working at the age of nine as a labourer in a cotton mill but a month later he left and spent a short period working for Lawrence Whitaker, one of the leading cotton manufacturers in the district, before taking a job in Stellfoxe's Victoria Mill in Baxenden. Here he was put to operate a spinning machine. On 8 May 1857 his right arm was entangled in a cogwheel and mangled so badly it had to be amputated. He did not receive any compensation.

Interior of a nineteenth-century cotton mill

When he recovered from his operation, a local benefactor, John Dean, helped to send him to a Wesleyan school, which was connected to the Methodist Church, and here he received a good education. In 1861, at the age of 15, he went to work in a local post office, owned by Henry Cockcroft, who also ran a printing business. Despite his injury, he learned to be a typesetter. He was later promoted to letter carrier and bookkeeper and worked in the printing office for five years.

Davitt took night classes at the local Mechanics' Institute and used its library. He became interested in Irish history and the contemporary Irish social situation under the influence of Ernest Charles Jones, the veteran Chartist leader, learning his radical views on land nationalisation and Irish independence.[2]

Fenians

In 1865, this interest led Davitt to join the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), which had strong support among working-class Irish emigrants. He soon became part of the inner circle of the local group. Two years later he left the printing firm to devote himself full-time to the IRB, as organising secretary for Northern England and Scotland, organising arms smuggling to Ireland using his new job as "hawker" (travelling salesman) as cover.

Davitt was involved in a failed raid on Chester Castle to obtain arms on 11 February 1867 in advance of the Fenian Rising in Ireland, but evaded the law. In the Haslingden area he helped to organise the defence of Catholic churches against Protestant attack in 1868. He was arrested in Paddington Station in London on 14 May 1870 while awaiting a delivery of arms. He was convicted of treason felony and sentenced to 15 years of penal servitude in Dartmoor Prison;[3] Davitt felt that he had not had a fair trial or the best of defence.

Dartmoor Prison

He was kept in solitary confinement and received harsh treatment. In prison he concluded that ownership of the land by the people was the only solution to Ireland's problems. He managed to get a covert contact to Irish Parliamentary Party MP John O'Connor Power, who campaigned against cruelty inflicted on political prisoners. He often read Davitt's letters into the records of the House of Commons, with his party pressing for an amnesty for Irish nationalist prisoners. Due to public furore over his treatment, Davitt was released (along with other political prisoners) on 19 December 1877, when he had served seven-and-a-half years, on a "ticket of leave". He and the other prisoners were given a heroes' welcome on landing in Ireland.

Davitt rejoined the IRB and became a member of its Supreme Council. Under pressure from campaigners, the British Government had introduced a concept of "fair rents" in 1870 as a part of the first of the Irish Land Acts, but Davitt continued to hold that the common people of Ireland could not improve their lot without the ownership of their land, and frequently insisted at Fenian meetings that "the land question can be definitely settled only by making the cultivators of the soil proprietors".

In 1873, while Davitt was imprisoned, his mother and three sisters had settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1878 Davitt travelled to the United States in a lecture tour organised by John Devoy and the Fenians (IRB), hoping to gain the support of Irish-American communities for his new policy of "The Land for the People". He returned in 1879 to his native Mayo where he at once involved himself in land agitation.

The Land War

A Land League poster from the early 1880s

In the 1880s, many people in the West of Ireland were suffering from the effects of the 1879 famine; 1879 was one of the wettest years on record and the potato crop failed for a third successive year. Davitt organised a large meeting that attracted (by varying accounts) 4,000 to 13,000 people in Irishtown, County Mayo on 20 April. Davitt himself did not attend the meeting, presumably because he was on ticket-of-leave and could not risk being sent back to prison in England. He made plans for a huge campaign of agitation to reduce rents. The local target was a Roman Catholic priest, Canon Ulick Burke, who had threatened to evict his tenants. A campaign of non-payment pressured him to cancel the evictions and reduce his rents by 25%.

On 16 August 1879, the Land League of Mayo was formally founded in Castlebar, with the active support of Charles Stewart Parnell. On 21 October it was superseded by the Irish National Land League. Parnell was made its president and Davitt was one of its secretaries. This group united practically all the different strands of land agitation and land movements since the Tenant Right League of the 1850s under a single organisation, and from then until 1882, the "Land War" in pursuance of the "Three Fs" (Fair Rent, Fixity of Tenure and Free Sale) was fought in earnest. The League organised resistance to evictions and reductions in rents, as well as aiding the work of relief agencies. Landlords' attempts to evict tenants led to violence, but the Land League denounced this.

One of the actions the Land League took during this period was the campaign of ostracism against the land agent Captain Charles Boycott in Lough Mask House outside Ballinrobe, Co Mayo, in the autumn of 1880. This campaign led to Boycott abandoning Ireland in December and coined the word boycott, which quickly spread across the world and through many languages. In 1881 Davitt was again imprisoned for his outspoken speeches after he accused the Chief Secretary for Ireland, W. E. Forster of "infamous lying". His ticket of leave was revoked and he was sent back to Portland Prison. Parnell protested in the House of Commons and the Irish members generally protested so strongly that they were ejected from the House. The government passed the Protection of Persons and Property Act 1881, allowing for internment without trial of those suspected of involvement in the Land War in Ireland, the latest in a series of around 105 suppressive laws designed to shut down protests in Ireland. Davitt was released from prison in May 1882, following the agreement of the Kilmainham Treaty, which promised to release imprisoned Land League members.

Davitt was a friend and mentor of Anna Parnell, founder of the Ladies' Land League and sister of Charles Stewart Parnell. [4]

Travels and marriage

Davitt c. 1982. The sign reads, "Land League, The Land for the People"

In an 1882 by-election Davitt was elected Member of Parliament for County Meath but was disqualified because he was in prison. On his release in 1882 he travelled to the United States with William Redmond to collect funds for the Land League, then campaigned for land nationalisation and an alliance between the British working class, Irish labourers and tenant farmers. This alienated Parnell and even many of the tenants, but after a meeting with Parnell at Parnell's house, Avondale, in September 1882 he agreed to co-operate with Parnell and set aside his plans for land nationalisation.

Davitt's support of the Irish National League, now under Parnell's and the Party's control, earned him a final spell in prison in 1883, and by 1885 his health had broken. Although only in his forties, he had become a post-revolutionary figure, and lectured on humanitarian issues in extended tours which included Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, South Africa, Palestine, South America, Russia and most of continental Europe, as well as almost every part of Ireland and of Britain.

In 1886 Davitt married an American, Mary Yore (b. 1861), daughter of John Yore of St. Joseph, Michigan. In 1887 he visited Wales to support land agitation.[2] The couple returned to Ireland and lived for a while in a Land League cottage in Ballybrack, County Dublin that was presented to them as a wedding gift by the people of Ireland. They had five children – three boys and two girls, one of whom, Kathleen, died of tuberculosis aged seven in 1895. One of their sons, Robert Davitt, became a TD, while another, Cahir Davitt, became President of the High Court.[5]

Davitt was a strong supporter of the alliance between the Liberal Party and the Irish Parliamentary Party and maintained this position in 1890 when the party split over Parnell's divorce case. Davitt, however, sided with the anti-Parnellite Irish National Federation faction in the House of Commons at Westminster, where he became hostile towards Parnell and was one of Parnell's most vociferous critics. He also became increasingly impatient with what he saw as the inability or unwillingness of the British parliament to right injustice.[citation needed] In 1888, Davitt launched an anti-semitic attack on George Goschen, 1st Viscount Goschen, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, arguing that he 'represented that class of bond-holders, and usurers, and mostly money-lenders for whom that infamous Egyptian war was waged'. [6]

Labour Federation and death

To further those ends he founded and edited a journal, Labour World, in September 1890, then initiated in January 1891 in Cork the Irish Democratic Labour Federation, an organisation which adopted an advanced social programme including proposals for free education, land settlement, worker housing, reduced working hours, labour political representation and universal suffrage. The Federation reflected his conviction, to which he adhered to all his life, that farmers' land proprietorship must go hand in hand with land nationalisation.[citation needed]

Davitt was subsequently elected for North Meath in the 1892 general election,[7] but his election was overturned on petition.[clarification needed][8] However he was promptly elected unopposed for North East Cork at a by-election in February 1893,[8] but resigned from the Commons on 9 May of that year.[9] At the next general election, in 1895, he stood in South Mayo, where he was returned unopposed.[10] He welcomed Gladstone's Second Home Rule Bill as a "pact of peace" between England and Ireland.[2] He supported the British Labour leader Keir Hardie and favoured the foundation of a Labour Party, but his commitment to the Liberal Party for the sake of Home Rule prevented him joining the new party – resulting in a breach with Hardie lasting until 1905.[11]

The House of Commons in 1851

Davitt resigned from the Commons again on 26 October 1899[9] with a prediction that no just cause could succeed there unless backed by massed agitation.[citation needed] Parliament alleviated this need by granting full democratic control of all local affairs, a form of "grass roots home rule", to County and District Councils under the 1898 Local Government (Ireland) Act. Davitt then co-founded in 1898 together with William O'Brien the United Irish League and organised it in Mayo and beyond. In 1899 he left his seat in parliament for good in protest against the Boer War, visiting South Africa to lend support to the Boer cause. His experiences inspired his Boer fight for Freedom, published in 1902.[12]

Davitt's ambition that the ownership of the land would be transferred from the landlords to the tenants finally materialised after the 1902 Land Conference under O'Brien's Wyndham Land (Purchase) Act (1903), but not as he had campaigned for. He condemned the act that offered generous inducement to the landlords to sell their estates to the tenants, the Irish Land Commission mediating to then collect land annuities instead of rents, on the grounds that landlords should not receive any compensation for land which Davitt felt belonged to the state. He never gave up his adherence to land nationalisation. Later in 1906 after the Liberal Party came to power, his open support for their policy of state control of schooling, rather than denominational education, merged into a major conflict between Davitt and the Irish Catholic Church.[13]

Davitt died in Elpis Hospital, Dublin on 30 May 1906, aged 60, from blood poisoning. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland attended the funeral, a public indication of the dramatic political journey this former Fenian prisoner had taken. The plan had been not to have a public funeral, and hence Davitt's body was brought quietly to the Carmelite Friary in Clarendon Street, Dublin. However, the next day over 20,000 people filed past his coffin. His remains were then taken by train to Foxford, County Mayo, and buried in the grounds of Straide Abbey at Straide (near Foxford), where he was baptized.[14]

Achievements

Michael Davitt's unceasing efforts were instrumental to future Irish Land Acts after the Gladstone First Land Act of 1870. The most important of these was the Land Act of 1881, which finally granted "the three Fs" under Davitt's "Irish Democratic Land Federation". The next stage was the 'Ashbourn Act (1885)'. The Ashbourne Act was the most effective land act as it offered tenants the choice to purchase their land from the government with a fixed rate, easy to pay back loan. Vast tracts of land were bought up by the government to be sold to tenants. This Act was passed by the Conservatives as an attempt to appease the Home Rule Party, although it failed to do so.

Davitt founded Labour World in 1890; the newspaper was an early promoter of the British Labour Party. His support for socialism in his latter years was based on the premise that Ireland could only achieve independence with the support of the British working class. This, along with his call for land nationalisation, often made him much misunderstood in Ireland.[11] But he remained an inspiration for many others, such as for D. D. Sheehan's Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA), and years later Mahatma Gandhi attributed the origin of his own mass movement of peaceful resistance in India to Davitt and the Land League.[15]

Davitt was a brave and proud man; an ascetic who accepted no tribute for his work; on occasions impatient with those who disagreed with him; sometimes expecting too much from the farmers, as in 1885 when he described them responding in 'self-interest' rather than 'self-sacrifice’.[2] He supported himself with writing and lectures and as a journalist defended the underprivileged. In 1903 he published the book Within the pale: The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia.[16] This was based on reports made by him to an American newspaper in 1903 on anti-Semitic outrages in Russia. He traveled to Russia to investigate the incident, whereby an anti-Jewish riot (the Kishinev pogrom) initiated in the town of Kishinev in the Russian province of Bessarabia, resulted in 51 people being killed and over 500 injured). Davitt, while opposing "cowardly racial warfare" such as the Kishinev pogrom, announced that he was "resolutely in line with... [the] spirit and programme" of antisemitism when it stood "against the engineers of a sordid war in South Africa, or as the assailant of the economic evils of unscrupulous capitalism anywhere". [17]

Back in Ireland in 1904 his Kishinevan experience of antisemitism inspired Davitt to unequivocally and passionately oppose the Limerick Boycott organised by the Redemptorist priest John Creagh: ‘I protest as an Irishman and as a Catholic against the barbarous malignancy of anti-semitism which is being introduced into Ireland under the pretended regard for the welfare of the Irish people.’[18]

Scotland

Davitt was a frequent visitor to Scotland where he was closely associated with the crofters' struggles in the Highlands and Islands. He also urged the Irish immigrant population to integrate into the politics of their adopted country and in particular the infant Labour movement rather than to pursue a particularly Irish agenda. Davitt worked closely with John Ferguson (1836-1906), the Irish leader in Glasgow who had been involved in the Crofters' War agitation by Highland tenant farmers in the early 1880s and later in the Irish-Radical political alliance that was the forerunner of the Scottish Labour Party.[19] Davitt made successful tours of Scotland in 1882 in 1887 denouncing landlordism. He had a major impact on Scottish Agrarianism, and movements for land reform, as well as on the Scottish labour movements. His Fenian past, prison record, and his personal story of overcoming eviction, exile, and physical disability won the attention of the Irish in Scotland. In turn Scotland helped broaden his political viewpoint, thanks to his association with Scottish nationalist and land reformer John Murdoch. These contacts led to a pan-Celtic solidarity with liberal radicalism and drew him to the radical movements in Scotland. He worked with Glasgow Irishmen Edward McHugh and Richard McGhee, which led him to the land philosophy of Henry George and provided him a political base in Glasgow.[20]

Wales

Rumblings in the 1880s indicated that agrarian unrest was a distinct possibility in Wales. David Lloyd George and T. E. Ellis brought Davitt to Wales in 1886 to campaign for reforms. Welsh reformers often compared their plight to Ireland, even though their situation was much better. Incomes were higher in Wales, and the relationships between tenant and landowner were generally friendly. There was no question of a tension between politically deprived Catholic tenants and privileged Protestant landowners. Reform languished in Wales as farmers showed little enthusiasm; reformers were divided among themselves; economic conditions improved in the 1890s, and a few moderate reforms satisfied the Land League.[21]

Reception

Extracts from an article to mark the centenary of Michael Davitt's death:[22]

| “ | He was only 24 years when he was imprisoned as a convicted felon for terrorist activities. Yet, Davitt learned from such adversity while in prison. He came to the conclusion, as he records in his Leaves from a Prison Diary, that violence was self defeating... [Davitt became] an apostle of non-violence... | ” |

| “ | While Parnell was venerated posthumously as a martyr, Davitt was excoriated as a Judas. Remarkably, by 1916, just 10 years after his death, Davitt had been deliberately air-brushed out of the script for Irish freedom... Insufficient attention has been paid to Davitt's role as an ex-Fenian who took the road of peaceful, democratic politics by renouncing his Fenian oath and taking a seat in the House of Commons at Westminster. He (would have) totally excluded violence as a means of advancing Irish unification. | ” |

Henry Hyndman, the leader of the British Social Democratic Federation looked upon him fondly referring to him as " the great Irishman" and "patriot"[23]

Memorials

Statue of Davitt at Straide Abbey

Over Davitt's grave a Celtic Cross in his memory bears the words "Blessed is he that hungers and thirsts after justice, for he shall receive it." At Straide, the Davitt family church is now a museum that commemorates his life and works. A life-sized bronze statue stands before it. [24]

Davitt College in Castlebar, County Mayo, Ireland is named after him.

The bridge from Achill Island to the mainland is named after him. The town of Haslingden, Lancashire, England has also commemorated Davitt's link with it through a public monument erected in the presence of Davitt's son. Haslingden also organised a 'Exile & Exiles' Festival in 2006 which did much to celebrate the life of Michael Davitt, as well as place it in the context of other immigrants to the community. This included 'The Jail Bird', a performance about Davitt, created by Horse and Bamboo Theatre with local school students.

The centenary of Davitt's death also saw the unveiling of a plaque at the Portree Hotel, Portree, Isle of Skye, commemorating his role in the Highland land agitation of the 1880s. The unveiling was carried out by his grandson, Fr. Tom Davitt.

A debate has also started on the extent to which Davitt altered his recall of the events in his remarkable life. One of Michael Davitt's biographers, Professor Moody, remarked in 1982 that Davitt's habit of: "..reinterpreting his past actions and attitudes in accordance with altered conditions was partly the outcome of a longing for integrity in his political conduct".[25]

Popular culture

Fenian author William C. Upton dedicated his 1882 novel Uncle Pat's Cabin to Davitt: "Noble Felon! with the fire of past events yet burning, and my pen dipped deep into the bosom of that spirit of which you are the embodiment, allow me to dedicate (this novel) to your enduring memory."- Irish folk musician Andy Irvine's 1996 Patrick Street song, "Forgotten Hero", is a tribute to Davitt.

- In 2006, Irish-born musician Donal Maguire released an album of songs based on Davitt's life, entitled Michael Davitt: The Forgotten Hero?.

- He is mentioned in James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

- Davitt was played by Donald Crisp in the 1937 film Parnell, which featured Clark Gable in the title role.

See also

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

Notes

^ Val Noone (2012), Hidden Ireland in Victoria, Ballarat Heritage Services, p. 103. .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 978-1-876478-83-4

^ abcd Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004)

^ Old Bailey Proceedings Online (accessed 27 January 2018), Trial of John Wilson, Michael Davitt. (t18700711-602, 11 July 1870).

^ Patricia Groves, "Petticoat Rebellion, The Anna Parnell Story," Mercer History, 2009.

^ Ruadhán Mac Cormaic,The Supreme Court, Penguin Ireland, 2016.

^ Eugenio F. Biagini. British Democracy and Irish Nationalism 1876–1906. Cambridge University Press,2007. 73

^ Brian M. Walker, ed. (1978). Parliamentary election results in Ireland 1801–1922. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. p. 148. ISBN 0-901714-12-7.

^ ab Walker, op. cit., page 150

^ ab Department of Information Services (9 June 2009). "Appointments to the Chiltern Hundreds and Manor of Northstead Stewardships since 1850" (PDF). House of Commons Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

^ Walker, op. cit., page 155

^ ab A New Dictionary of Irish History from 1800, p.105-105, D. J. Hickey & J. E. Doherty, Gill & MacMillan (2003)

ISBN 0-7171-2520-3

^ Michael Davitt (1902). The Boer Fight for Freedom. Funk & Wagnalls.

^ Biography "The long Gestation, Irish Nationalist Life 1891–1918" pps. 83, 225, Patrick Maume (1999)

^ Michael Davitt Museum, Straide, County Mayo, http://www.michaeldavittmuseum.ie/history/

^ Dailey, Lucia (17 March 2013). "Irish patriot left worldwide mark". Scranton, Pa. Scranton Times Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

^ Davitt, M. (1903). Within The Pale: The True Story of the Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia. New York: The Jewish Publication Society of America. Retrieved from http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/urn/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30-180013272008

^ Renshaw, Daniel. "Prejudice and Paranoia: A Comparative Study of Antisemitism and Sinophobia in Turn-of-the-century Britain." Patterns of Prejudice 50.1 (2016), p.45

^ Kevin Haddick Flynn, The Limerick pogrom, 1904 (History Ireland, Vol. 12, summer 2004)

^ Terrance McBride, "John Ferguson, Michael Davitt and Henry George - Land for the People," Irish Studies Review (2006) 14#4 pp 421-430.

^ Máirtín ÓCatháin, "Michael Davitt and Scotland," Saothar (2000), Vol. 25, pp 19-26

^ J. Graham Jones, "Michael Davitt, David Lloyd George and T.E Ellis: The Welsh Experience." Welsh History Review [Cylchgrawn Hanes Cymru] 18#3 (1997): 450-82.

^ Michael Davitt: Still in the shadow of the gunmen, John Cooney, Irish Independent, 27 May 2006

^ https://www.marxists.org/archive/hyndman/1912/further/ch02.html

^ Michael Davitt Museum, Straide, County Mayo, http://www.michaeldavittmuseum.ie/history/

^ Moody TW "Davitt and the Irish Revolution" (Oxford 1982) page 552.

Works

Wikisource has original works written by or about: Michael Davitt |

- Michael Davitt, The Prison Life of Michael Davitt (1878)

Davitt, Michael (1882). . Glasgow: Cameron & Ferguson.- Michael Davitt, Leaves from a Prison Diary (2 vols) (1885)

- Michael Davitt, Defence of the Land League (1891)

- Michael Davitt, Life and Progress in Australasia (1898)

- Michael Davitt, Within the Pale, The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia (1903)online

- Michael Davitt, Boer Fight For Freedom (1904)

- Michael Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland (1904)

ISBN 1-59107-031-7 - Michael Davitt, Collected Writings, 1868–1906 Carla King (2001)

ISBN 1-85506-648-3 - Michael Davitt, The "Times"-Parnell Commission: Speech delivered by Michael Davitt in defence of the Land League (1890)

- Irish Political Prisoners, Speeches of John O'Connor Power M.P., in the House of Commons on the Subject of Amnesty, etc., and a Statement by Mr Michael Davitt, (ex-political prisoner) on Prison Treatment (March 1878)

Further reading

- Armstrong, Allan. From Michael Davitt to James Connolly: 'Internationalism From Below' and the Challenge to the UK State and British Empire From 1879-95 (2010)

- Cahalan, James M. "Michael Davitt: The'Preacher of Ideas,'1881-1906." Êire-Ireland 11.1 (1976): 13-33. short scholarly biography

- Flynn, Kevin Haddick. "Davitt – Land Warrior" History Today May 2006)

- Foster, R. F. Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890-1923 (2015) excerpt

- Jordan, Donald E. "Michael Davitt: Activist Historian." New Hibernia Review 5.1 (2001): 141-145. online

- King, Carla Michael Davitt After the Land League 1882-1906 (Dublin, 2016)

- King, Carla Michael Davitt (Dundalk, 1999)

- Lane, Fintan and Andrew Newby (eds), Michael Davitt: New Perspectives, Dublin (2009)

- McBride, Terence. "John Ferguson, Michael Davitt and Henry George—Land for the People." Irish Studies Review 14#4 (2006): 421-430.

- Marley, Laurence. Michael Davitt: Freelance Radical and Frondeur (Four Courts Press, 2007)

ISBN 978-1-84682-066-3

Moody, T. W.: Davitt and Irish Revolution 1846–82 (Oxford UP, 1981)- Moody, Theodore W. "Michael Davitt and the British Labour Movement 1882-1906." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (1953): 53-76. in JSTOR

O'Hara, Bernard. Davitt: Irish Patriot and Father of the Land League, Tudor Gate Press (2009)

ISBN 978-0-9801660-1-9

O'Hara, Bernard. Michael Davitt Remembered, The Michael Davitt National Memorial Association (1984) ASIN B0019R83VG- Stanford, Jane. That Irishman The Life and Times of John O'Connor Power (The History Press Ireland, 2011)

- The Michael Davitt National Memorial Association Michael Davitt Remembered, (1984) ASIN B0019R83VG

Primary sources

- D. B. Cashman and Michael Davitt, The Life of Michael Davitt and the Secret History of The Land League (1881)

- Davitt, Michael. The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland: Or, The Story of the Land League Revolution (1904) online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michael Davitt. |

- Michael Davitt Portrait Gallery: UCC Multitext Project in Irish History

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Michael Davitt

- The Michael Davitt Museum, Straide, Foxford, Co. Mayo

Institutions

- Michael Davitt Museum, County Mayo, Ireland

- The Irish Democratic Club, (Davitt Branch) in Haslingden, the town where Michael Davitt was brought up

Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alexander Martin Sullivan Robert Henry Metge | Member of Parliament for Meath 1882 With: Robert Henry Metge | Succeeded by Edward Sheil Robert Henry Metge |

| Preceded by Pierce Mahony | Member of Parliament for Meath North 1892 | Succeeded by James Gibney |

| Preceded by William O'Brien | Member of Parliament for Cork North-East Feb. 1893 – May 1893 | Succeeded by William Abraham |

| Preceded by Jeremiah Daniel Sheehan | Member of Parliament for Kerry East 1895 | Succeeded by James Boothby Burke Roche |

| Preceded by James Francis Xavier O'Brien | Member of Parliament for Mayo South 1895–1899 | Succeeded by John O'Donnell |